Nathalie at her painting desk, in front of the large picture window in her studio.

Nathalie at her painting desk, in front of the large picture window in her studio.

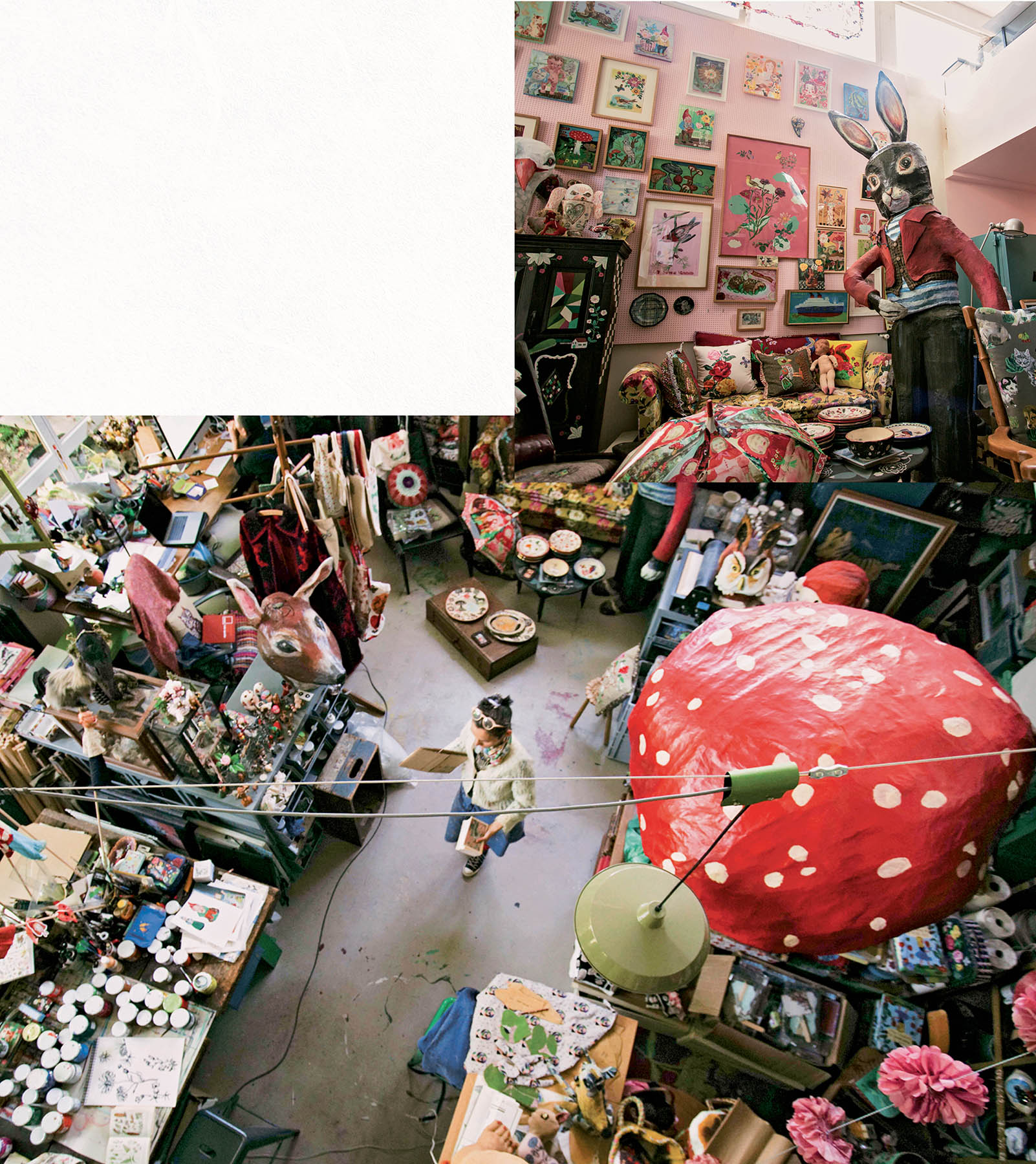

Labyrinth, fairy tale, fantasy, carnival, treasure chest, bazaar, wonderland . . . all these words come to mind when I step inside Nathalie Lété’s enchanting two-level studio, housed in a former iron factory complex in Ivry-sur-Seine, a southern suburb of Paris. I hear birds chirping and at first assume they are coming from the white canary in a wire cage near a wall of windows, but the chirping is a sound track Nathalie plays because she likes to feel as though she’s in the forest when she works.

Nathalie is simultaneously down-to-earth and ethereal, waiflike and modelesque—she looks as though she could be a ballerina. She is wearing a blue, paint-splattered apron over a blue dress, a hand-knitted mohair lace cardigan, cherry-red tights, blue Converse high-tops, a beaded necklace, and a silk floral scarf of her own design. The scarf is wrapped around her neck in that effortlessly chic way that seems to be in a Frenchwoman’s DNA. Or maybe it just comes from spending one’s life in France, since Nathalie, though a French citizen since age twelve, is the only child of a German mother and a Chinese father.

A detail of Nathalie’s painting Les Lapins (Rabbits).

Nathalie’s fascination with fairy tales began early and was nourished by her mother, who read them to her at bedtime and dressed her in a red cape that earned her the nickname le Petit Chaperon Rouge (or Little Red Riding Hood), and her beloved grandmother, who, when Nathalie visited her in Bavaria in wintertime, would take her into the forest to fill mangers with straw for the deer. About those early walks, Nathalie wrote the following for an article in Flow magazine:

Cela m’a profondément marquée. Elle était habillée de façon traditionelle, tablier et foulard sur la tête. . . . Je me voyais princesse d’une forêt enchantée, entourée de biches, de nains, de champignons, de fleurs magiques et même du prince charmant. (That affected me profoundly. She was dressed in a traditional way, apron and head scarf. . . . I saw myself as a princess of an enchanted forest, surrounded by does, dwarves, mushrooms, magical flowers, and even Prince Charming.)

Hand-sewn and -painted dolls, part of a butchery series that began with drawings that evolved into dolls, then ceramic pieces, then meat motifs on a variety of products, including rugs and plates.

Her childhood wasn’t easy, as her parents did not get along well (and, ultimately, divorced) and her father was involved in some precarious business dealings that put the household on edge both economically and emotionally. The art she makes today, she says, is very much like that which she created as a child, reflecting an imaginary, fairy tale–like world in which she continues to seek refuge. “When I am making my art, I feel calm. I feel with myself. I am not thinking about outside,” she says. “I’m not interested in speaking about the real world. Modernity doesn’t interest me. I can survive if it is terrible outside. I feel it is easier when you are a bit cut off from others and you do things your own way.” And it is alone in her studio that Nathalie is able to spend most of her time now that her children (a son and a daughter) are young adults.

Nathalie grew up in another Parisian suburb southwest of this studio and the home, also in this complex, where she now lives with her family. “We work all the time,” Nathalie tells me about herself and her husband, artist Thomas Fougeirol, whose studio neighbors Nathalie’s and whose minimalist, abstract paintings exploring absence and disappearance could hardly be more different from her own multicolored, narrative expressions. What Nathalie shares with her husband, she says, is devotion to their creative purpose. “We both have complete passion for what we are doing. We understand why the other one’s mind is always so self-focused because we are the same in that way.”

The two-level studio is packed with Nathalie’s artwork as well as samples of products from the many companies with which she collaborates.

Nathalie’s propensity for making by hand—everything from drawing and painting to knitting, crochet, silkscreen, and ceramics—has been with her for as long as she can remember. As a teenager, she sold her drawings and hand-painted silk scarves to earn pocket money and to help support her family; however, upon finishing her baccalauréat (the French equivalent of a high-school diploma), she did not imagine pursuing a career as a maker. She thought she might become a flight attendant, which she saw, like her art, as a means of escape, but with a surer path to financial security. Before applying for an airline job, however, Nathalie went to see an astrologer who was so certain she could become a successful artist that she convinced her to change course. Nathalie went on to study fashion at Paris’s École des Arts Appliqués and then lithography at the famed École des Beaux-Arts (the same school where Renoir and Matisse and so many French masters learned to paint), finishing in 1993 and never looking back. She credits the rigor of the program at the École des Arts Appliqués for helping her develop her work ethic as well as her understanding of the commercial side of creative production. At Beaux-Arts, she had a well-equipped studio at her disposal day and night, so plenty of time to refine her technique.

Today Nathalie earns a living as an independent artist by creating one-of-a-kind artwork, designing products to sell directly to customers, and licensing imagery for use on a vast array of goods around the world—from children’s puzzles and lunch boxes to cosmetics and clothing to fabric and wallpaper. As when she was a child, she moves from medium to medium as her interests dictate, unfazed by distinctions and judgments others like to make about the value of art vs. craft vs. manufactured goods. “In fact, I don’t care,” she says. “I wouldn’t like to work only with art galleries. To work with a fashion brand is as interesting to me as working with an architect or with a butcher shop.” Actually, pieces from a meat-themed series Nathalie began out of her own curiosity did make it into a Parisian butcher’s window, as well as into a 2015 retrospective of her work at the La Piscine museum in Roubaix in northern France, and into John Derian’s boutique in New York.

Nathalie stores hundreds of pieces of artwork in these flat files. Before they are placed there, she scans them, then an assistant cleans and separates the motifs so they can become part of a vast bank of imagery that she can easily access (and mix, match, and layer, as necessary) when a client calls or emails with a request.

Although many of the products Nathalie designs these days are ultimately produced by others, they all begin in her studio. “Making things with my hands makes me feel happy and optimistic and gives me confidence,” Nathalie explains. “People say, ‘I think, therefore I am.’ I say, ‘I make, therefore I am.’ ” And by extension, she is drawn to what others make by hand as well. “I am attracted to things in which I can feel the human hand—its gesture, its force, its patience, its dexterity,” which is in keeping with her affection for folk art, and the desire to make the most utilitarian of objects beautiful for the enhancement of everyday life.

Nathalie’s creative vision is, indeed, all-encompassing. Each product is more than a single object, she says, but part of a larger story. For her showroom in the center of Paris, about 400 square feet in a former button factory, she created a full living space—kitchen and bath included—with nearly every detail made and/or designed by her: It began with an entire ceramic wall, consisting of three hundred tiles on which she hand-painted birds amid more abstract, decorative motifs. (About painting birds, she wrote in her 2017 book, In the Garden of My Dreams, “When I paint them, their free spirits embody me, and I can feel the freedom they must have when they fly in the sky.”) A nest-like bed is suspended from the ceiling, its interior walls hand-painted with flowers. Nearby are a wooden tree sculpture and a table, chair, and stools sculpted to look like flowers.

Nathalie painting flowers based on artwork in one of her many reference books. When she is engaged in handwork, she says, her senses are awakened.

Similarly, in collaboration with the French department store chain Monoprix, Nathalie has created all-immersive pop-up shops. In Tokyo, her fans can shop at Le Monde de Nathalie, a retail space stocked only with her creations. For customers who desire a similar albeit less encompassing effect, Nathalie enjoys painting display windows, something she has done many times in Japan and also at Loop in London and at Anthropologie on New York’s Fifth Avenue. And for herself, she is refurbishing a hilltop nineteenth-century house on the edge of the Fontainebleau forest, a home in the country where the fantasy world of her art will merge more intimately than ever with her daily reality. There, every surface will become a canvas, no detail too small for her creative attention. “An art house,” she says, “because I have to express myself.”

A few months after visiting Nathalie in her studio, I see her again in New York, at a book signing for In the Garden of My Dreams. When I walk in, she is seated behind a table festooned with fresh flowers, a stack of books, and some art supplies she has brought with her from France. She stands up and greets me warmly, then returns to her work, which includes composing a personal note and a special illustration with colored pencils and rubber stamps (her own owl, deer, and tree) for each book and its recipient. While guests mill around chatting and sipping wine, Nathalie sits peacefully at her table working. Dressed in jeans and a sweater with a floral-garland motif based on her artwork (a limited edition for the Japanese brand Antipast), and with butterfly clips glittering in her hair, she looks serene and safe, somehow present but separate from the hubbub of customers around her. Elegant and chic and with a childlike focus, she is absorbed in a world of her own making.

Nathalie has some of her paintings reproduced on silk scarves (like the one shown here). Although she often works with seemingly childlike imagery, the overall effect somehow transcends age. When I mention to her that there is a darkness in her work despite the seeming sweetness of many of her subjects, she says matter-of-factly, “It is like life.”

Nathalie walking outside her studio with her dachshund, Spike. She can easily visit her husband’s studio, which is in the same building, or head home, just a five-minute walk from here, in the same complex (a former iron factory where part of the Eiffel Tower was built).

In the garden (meant to look like a forest floor) in front of Nathalie’s studio sits a chair upholstered with fabric she designed, plus a hand-embroidered cushion based on her artwork. The flower stool is an extra piece from the collection of custom furniture that she commissioned a local woodworker to create for her Paris showroom.

“I am attracted to things in which I can feel the human hand—its gesture, its force, its patience, its dexterity.”

Nathalie sewing a prototype Bambi doll using fabric from the Japanese fashion and textile brand Minä Perhonen. This collaboration was organized to coincide with the release of a new edition of the Austrian author Felix Salten’s original Bambi story (published by Cernunnos), which Nathalie illustrated.