In the summer of 2012, I attended the Yale Publishing Course, a one-week professional workshop on the school’s campus in New Haven, Connecticut. At the time, I had already been working in the book industry for more than two decades and was the publishing director for STC Craft / Melanie Falick Books, an imprint of the New York publishing house Abrams. In this role, I focused on subjects I enjoyed and valued, such as knitting, sewing, quilting, printing, pottery, and other forms of creativity. I took great pride in my work and, having written five books myself, was in the somewhat unique position of genuinely understanding many of the challenges my authors faced when transforming the seed of an idea into a physical object to present to the world.

When I heard about the Yale program, which was billed as five days of lectures and discussions on the future of book publishing in the new global and digital landscape, I was intrigued. Once I arrived, however, I quickly realized that the emphasis would be more on the financial side of the business than the creative, leaving me feeling a bit like a square peg in a round hole.

Late one afternoon, I was relieved when Nigel Holmes entered our amphitheater-style classroom and gave an energetic presentation about his career as a graphic designer, art director, and illustrator. Holmes is internationally renowned for his work in information graphics (distilling complex data and ideas into appealing, easy-to-understand visual forms), and he began and ended his lecture by holding up a simple wooden boat that he had carved for his grandson. With that small handmade object, he reminded us to never let the lure of technology or business overshadow the value we place on working with our own hands. I left the classroom, walked straight to the bathroom, looked down at my hands, and started to cry.

Before going to sleep that evening, I wrote an email to Nigel to thank him. Early the next morning, I was happy to wake to a response:

What a nice message . . . thank you very much for taking the time to write (and at such a late hour!). Like you, I feel a bit lost at conferences such as this one, and I know that I should really attend all the sessions as a participant (not as a nervous presenter, just waiting for the one before mine to end), but I have generally gone through life using intuition more than focused reasoning, and it seems to have supported me so far. I very much like the feel of the books I can see on your site . . . you seem to be making beautiful books that encourage the kind of lifestyle that I was advocating last night: Technology is a great tool, but it will never be a substitute for human work and ideas. Keep looking at your hands.

Lavender at Chateau Dumas (see page 134).

Just shy of three years later, I left my full-time job at Abrams without a definitive plan for what I would do next, feeling sure I was making the right decision—and also excited and a little nervous. Looking back now, I realize that it was in the bathroom at Yale, after Nigel’s lecture, that I began to accept that it was time for me to move on professionally. I was in tears because he had broken through the mental facade I had built to protect myself from confronting the scary reality that I was in a job that had, for a long time, been ideal but that would not suit me much longer. Although I was making a good living, I was no longer making a good life. I was so caught up in emails, deadlines, profit-and-loss statements, sales reports, social media stats, and worries about being financially prepared for retirement that I wasn’t enjoying the present. Although I was publishing books about creativity, personally, I felt stuck—stressed and disconnected from my own dreams and values. I knew that if I didn’t make a change, I would come to regret it.

My ideas for the future were vague: Aside from part-time freelance work I had lined up to cover bills, a two-week intensive graphic design course that I’d been talking about enrolling in for years, some family obligations, and an intention to spend more time in the garden, I didn’t know what I wanted to do next. I just knew that I needed time to be quiet and let my mind wander. I recognized that after working for fifteen years within a corporate structure, I needed to set myself free of certain conventional dialogues about what was and wasn’t possible, plausible, dreamable, so that instead of feeling trapped, I could reignite my passion and identify the opportunities that I knew had to exist but that I could not yet see.

During an idyllic visit to Chateau Dumas for two weeks of making, I felt I was exactly where I was meant to be. In my bedroom each evening, I would open the windows and shutters to welcome the breeze, and in the morning, I would close them to block out the day’s heat, a simple ritual that contributed to my sense of connection and belonging.

Not surprisingly, given the calm and satisfaction that handwork brings me—a realization I came to when I became an avid knitter in my twenties (and then quickly decided to meld my interest in it with my burgeoning career in publishing)—over the next few months, I spent many hours making things. Most of my endeavors were easy and small but required that I try something new. I did some shibori dyeing with indigo, carved stamps, lattice-laced my sneakers, and dyed socks with madder root. I learned to use a strap cutter and a beveler to make leather bracelets, and I inserted my first zipper when I hand-stitched a pencil case out of repurposed Tyvek. Together with a woodworker friend, I built a bed swing for my porch. To my surprise, the most enlightening project was the simplest and seemingly most mundane: a box I created by strategically folding an ordinary piece of paper. Transforming that commonplace material, in just a few minutes, into a receptacle in which I could store something felt magical. It was so basic—almost primal. It was a skill that, like making my own clothing and growing my own vegetables, could have helped me survive if I had lived a very long time ago. In that box, I might have safeguarded seeds, small tools, or precious stones.

As I held my box in my hands, I realized that, in a circuitous way, during the last few months, I had been attempting to connect to my own survival. Even though I didn’t need to make my own clothing, boxes, or bed—or much of anything—to stay alive, I needed that bond to feel whole, competent and grounded, connected to my heart and soul, to my community, to my ancestors, and to the natural world around me. And, as a result of giving myself time to wander and to make, I no longer felt lost: I understood myself better and had found a new course. For starters, I would meld my personal and professional interests by writing another book of my own, one investigating and celebrating the role making by hand can play in making a good life. As an editor, I always told prospective authors that I was interested in the ideas that were bubbling out of them—the books that they couldn’t imagine not writing. That is what Making a Life became for me.

In Bagru, India, I watched as Dheeraj Chhipa submerged cloth block-printed using a mud-resist technique called dabu into a twelve-foot-deep indigo vat that his family has been dyeing in for more than twenty-five years. Dheeraj and his father, Rambabu, then spread the cloth on the road to dry. Chhipa means “printers” in Hindi. The Chhipa family have been block printers in India—and before that, Pakistan—for more generations than they can count.

In a factory near Delhi, India, these women were assembling thousands of heart-shaped felt wreaths for an American big-box store.

THE JOURNEY I took to write this book was idiosyncratic, guided mostly by my following leads from one person and place to the next. I explored, I listened intently, I took notes, I made things, I overcame fears and challenges. In the process, I felt true to myself and fully engaged. For practical reasons, I focused most of my attention on makers in the United States, but I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to travel abroad at least some of the time. I love learning about how people around the world live, especially by way of their making traditions, and I know that one of the best ways to begin to understand one’s own culture is to see it through the lens of another.

It seems like a miracle to me now that early on in the development of this book, more by happenstance than meticulous planning, I ended up in Jaipur and New Delhi, India, and soon thereafter in Oaxaca, Mexico. These trips helped me hone my perspective on what it means to make by hand and start to comprehend how it relates to economic development and globalization. I traveled to India with a team from an American homewares company. I accompanied them first to Bagru, in Jaipur, where we met Dheeraj Chhipa, who studied art at the Indian Institute of Crafts and Design and is trying to maintain his family’s multigenerational block-printing legacy by modernizing their traditional aesthetic, improving the quality of their base fabric, and reaching out to the international luxury market. Next we went to factories where textile products are made, often by hand, on a much larger scale. I quickly saw that the weaving, tufting, and braiding of rugs, stitching of pillows, and screen-printing of cloth for mass consumption that the workers there were doing is very different from the kind of textile-making I do at home, where I am able to choose what I want to make based on my own needs and tastes and then produce it from start to finish according to my schedule and whims. In these factories, in most cases, each worker was a member of a team responsible for one step of a process (such as winding yarn, warping looms, hemming, correcting errors, or even folding). I hope that the workers felt pride in what they created together, but I suspect they were there more for a paycheck with which to support their families than for the satisfaction of seeing a pile of their products being loaded onto a truck so they could be shipped abroad for consumption—or for the kind of existential satisfaction many makers experience when they are working with their hands for the sheer pleasure of it.

Of course, India’s economy is unique to its own history, culture, and political climate, so Indians are approaching making by hand and by machine in their own way. The government as well as many businesses there are eager to lure manufacturing work to their shores, while in the United States, we are sending so much of ours abroad. And even though Indians are increasingly pursuing higher education and seeking the better-paying jobs subsequently available to them, there is still a large population ready and willing to work in factories, some from families that have been doing handwork for generations. But much of the factory work is different from their traditional handwork, as it is designed for large-scale commerce, not to maintain or safeguard their skills or heritage.

To make the pottery they fire in their courtyard, the Mateos first gather clay from the nearby landscape. Among the tools they then use to make their vessels are a corncob for forming and shaping the bodies, a river stone for burnishing the clay surfaces, and a scrap of leather for giving form to the rims.

Not long after my trip to India, I departed for the state of Oaxaca in Mexico, another country with long-standing and exquisite handmaking traditions that are being challenged by social and economic changes. I was there to participate in a one-week program focused on creativity and making as an expression of culture, hosted by the Pocoapoco residency. One of the highlights of my experience was a visit to the village of San Marcos Tlapazola, where I met the Mateo family—eight sisters, in-laws, and nieces for whom pottery is a way of life. In the large central courtyard of the bright pink house they share, they make pottery following the age-old traditions passed down to them by their parents and grandparents.

What struck me most as I watched these women was how organic and immediate their process was—they dig clay nearby, from a cornfield and the Sierra Sur mountains, and they fire it in the open air with dried agave leaves and other brush, corncobs, and donkey manure that they store on their roof and then toss down into the courtyard when they need it. Though they make some vessels in nontraditional shapes to meet demand from foreign customers as well as Mexicans, most pieces are still based upon the local culinary traditions: flat plates that are perfect for the corn tortillas that accompany almost every meal, a large comal (or griddle) for cooking those tortillas, a deep olla for boiling beans. The Mateo family, who are Zapotec (one of the sixteen indigenous groups in the state of Oaxaca), literally hold the history of their craft and culture in their hands.

Alice from Saudi Arabia (by way of Belgium), Maria from the United States, Gillian from Ireland, and I take a break during our printing workshop with Lotta Anderson (see page 170) on Åland in the Baltic Sea.

Making by hand, it helps to remember, goes back to the beginning of human history and has developed in its own unique way in every culture. It is, in fact, our hands, especially our opposable thumbs (which allow us to make and use tools)—as well as our abilities to stand upright and make fire—that differentiate us most profoundly from our ape forebears. For hundreds of thousands of years, every object in the world that didn’t occur in nature was made by hand—vessels like the ones the Mateo family still make, tools, cloth, shelters, wagons, ships, musical instruments, and on and on. Hands and human ingenuity assured survival. The purpose of each day was to do what was necessary to stay alive, which meant many hours of handwork.

It wasn’t until the eighteenth century, when the industrial revolution began in parts of Europe and North America, that water and steam power and then electricity began to mechanize, and thus speed up, production, in turn reducing the necessity for human touch and increasing the ease of acquisition (and subsequent dispensability) of material possessions. And then the twentieth century saw the emergence of the digital revolution. Over the course of just a couple of hundred years in the so-called developed world, we have become passive consumers of products, services, and information rather than active makers, fixers, and even thinkers. Most of the time, what we buy is made somewhere else, by a machine or by people we’ll never meet, sometimes working in conditions we would not accept for ourselves.

Given these circumstances, it’s not surprising that some of us are discomfited and feel a need for a grounding counterforce. Just as the mechanization and mass production of the industrial revolution led to the Arts and Crafts movement (a late 1800s revival of interest in skilled handwork, craftsmanship, and refined design), the speed and anonymity of the digital revolution and the profit-driven globalization it fast-forwarded have led to what I call a DIY renaissance: a renewal of attention paid to the value of handwork as well as a concern about how what we consume is affecting our health and the environment. No longer required to make with our hands in order to assure our survival or make a living, more and more of us now do so by choice. What was once a necessity has become, for many, a joy, a privilege, and a call to action. The DIY renaissance is part of the same impulse that continues to drive the slow fashion, slow design, and slow food movements.

I believe that impulse to use our hands to make things and, in the process, to make them beautiful, is our evolutionary birthright. It is this concept that scholar Ellen Dissanayake has spent her life studying, and it is with a conversation with Ellen on the following pages that I invite you to join me on this journey. From there, I hope that you will enjoy reading about the lives of the many makers I met and spent time with during this extraordinary adventure. I’ve loosely organized their stories into five chapters—Remembering, Slowing Down, Joining Hands, Making a Home, and Finding a Voice—each one an answer to the question of what it is we stand to gain when we make things by hand.

All the people featured on these pages are, without a doubt, very talented; however, I chose them not because they are “the best” but because the way they are leading their lives is both relatable and inspiring. For some, making by hand is a way of earning a living—but more important for each of them, it is a way of taking agency over their own lives. They have shown me what their version of a good life looks like. I, in turn, am sharing their stories—and my own—with you.

We all make many choices in our lives, more than we sometimes recognize. I hope that reading this book motivates you to carve out some space in your routine to listen to what your inner voice, your soul, is telling you about what matters to you most; to tune in to the small decisions you make each day that determine how you spend your time and, ultimately, shape the life you lead.

And, of course, I hope you will keep looking at your hands. They may hold more answers than you realize.

That’s me under the gray protective helmet, welding with assistance from Dan Dyer in Austin (see page 158).

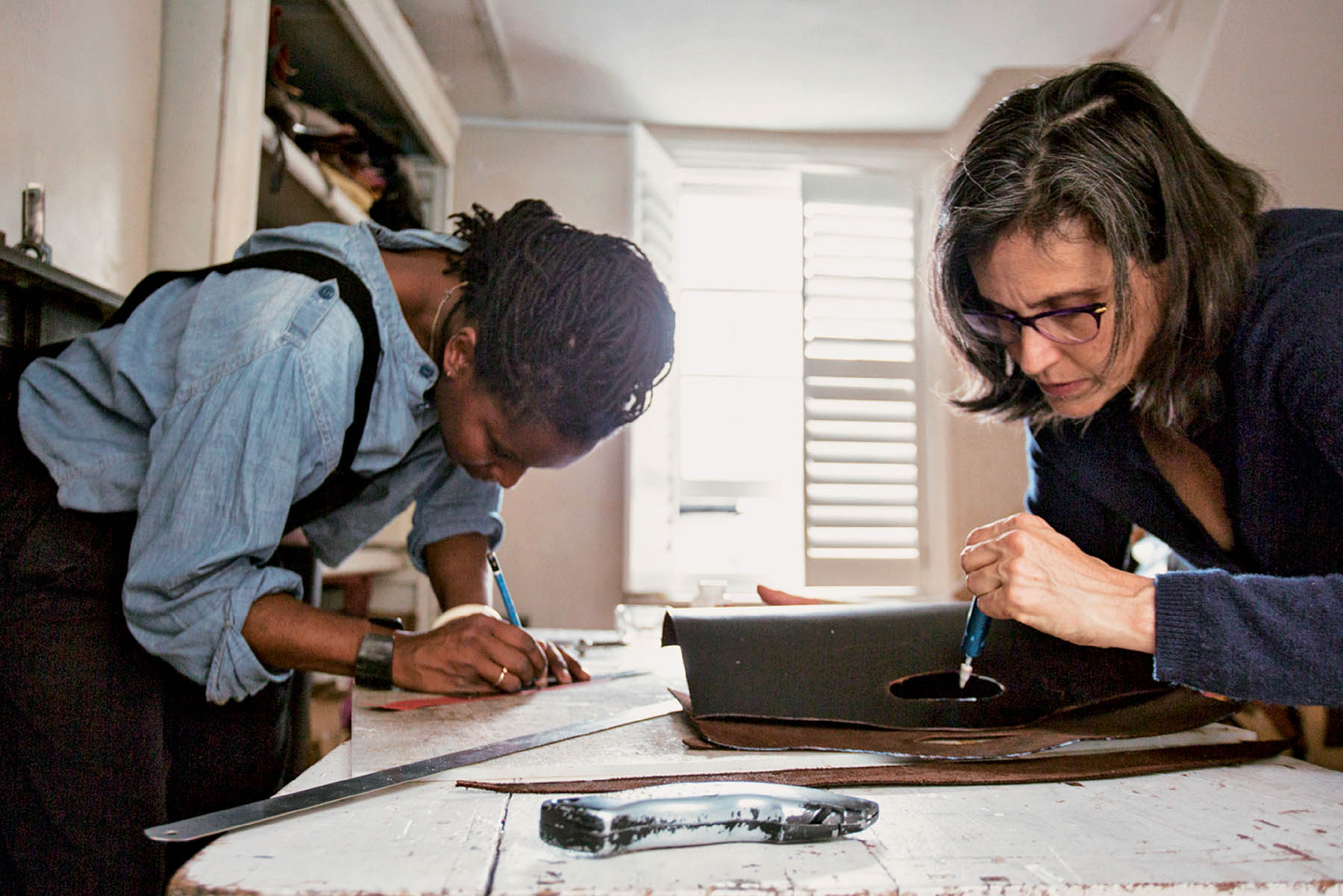

Dolores Swift (see page 306) and I hard at work on our leather bags.

Elsa Mora (see page 150) and I take a walk on her property in New York’s Hudson Valley.

A Conversation with Ellen Dissanayake

Making the Ordinary Extraordinary

Ellen in her Seattle home.

“The fact that it feels good to make things with our hands harkens back to our hunter-gatherer nature, which lives on in our psychology.”

When I began working on my first book, Knitting in America, which was published in 1996, I remember pondering two questions: Why do we want to make things with our hands, and why do we want to make them beautiful? Although those questions were continually on my mind as I traveled around the country interviewing knitters, I never addressed them directly in the book. I simply stated matter-of-factly that making by hand and making things beautiful are innate desires. I came to that conclusion based on my own experiences, conversations with other makers, and talking to scholar Ellen Dissanayake and reading her seminal article “The Pleasure and Meaning of Making,” which was originally published in American Craft magazine (and is now available on academia.edu).

When I began working on this book, I found myself asking the same questions but this time exploring them more deeply. My sister-in-law, who is an artist—and, coincidentally, once attended a dinner party with Ellen—reminded me about Ellen’s writings, so I reached out to her again all these years later. Fortunately, she greeted my inquiry with kindness and generosity and offered to help me in any way she could.

Meeting Ellen in person about six months later in her book-and-art-filled one-bedroom apartment in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle was a highlight of this project. She had just had her eightieth birthday and was healthy and still passionate about studying and sharing her ideas. A self-motivated and mostly self-taught scholar with a bachelor’s degree in music and philosophy from Washington State University and a master’s degree in art history from the University of Maryland, she has devoted much of the last fifty years to pursuing her interests in art and evolution (questions of how and why art originated and evolved) and how they relate to such subject areas as evolutionary biology, psychology, neuroscience, anthropology, and paleoarchaeology. Today she is considered a global authority. When I was with her, she had just completed her fourth book, Early Rock Art of the American West (with coauthor Ekkehart Malotki), and was preparing to give a lecture on animal and human behavior at a conference in Portugal.

In many ways, Ellen’s writings about art and making and her conviction that both are universal biological impulses inherited from our hunter-gatherer ancestors have helped me appreciate my own desires and choices. Recognizing that these impulses are literally wired into me genetically has helped me understand who I am, prioritize the role of making in my life, and trust that my efforts to encourage other makers—as a writer, editor, occasional teacher, and friend—are useful and worthy. I include this conversation with Ellen in hopes that her ideas will similarly comfort, challenge, and enlighten all who read it.

Ellen and I talked for hours about our mutual fascination with the human impulse to make ordinary things extraordinary.

What compelled you to study the relationship between human evolution and art and making?

I started out as a pianist, then was a housewife in two thirteen-year marriages. During this time, I was able to travel a lot in non-Western countries like Madagascar, India, Nigeria, and Papua New Guinea and to live in Sri Lanka for fifteen years. I wondered why the arts were so omnipresent and emotionally moving everywhere in the world. Because my interests were so multidisciplinary, I didn’t fit into any academic track, and I had to pursue my research on my own. Gradually, I began to publish my writings in the mid-1970s. I have traced what modern and postmodern societies call “art” (and “craft”) back to the toolmaking and ceremonial practices of our human ancestors.

In your first book, What Is Art For?, published in 1988, you presented a new definition of art.

It was less a new definition than a new approach—the idea of treating art as a behavior, something that people do, rather than as a thing or a quality or a label that museum curators give or that critics write about. I gradually came to the conclusion that in its most simple sense, art (as a verbal noun that I now call “artifying” or “artification”) is the act of making ordinary things extraordinary. It is a uniquely human impulse.

So you believe that artifying is an inherent, universal trait of the human species?

Yes. I believe that artifying is as normal and natural as language, sex, sociability, aggression, or any other characteristics of human nature. One could say that the general behavior of artifying (making things one cares about special) underlies all the arts.

Ellen’s living room shelves are filled with mementos from the more than two decades she spent living in Sri Lanka, traveling in Nigeria, and teaching at the National Arts School in Papua, New Guinea.

You coined the term joie de faire—an inherent joy in making—and in “The Pleasure and Meaning of Making,” you wrote that “there is something important, even urgent, to be said about the sheer enjoyment of making something exist that didn’t exist before, of using one’s own agency, dexterity, feelings, and judgment to mold, form, touch, hold, and craft physical materials, apart from anticipating the fact of its eventual beauty, uniqueness, or usefulness.” From an evolutionary perspective, why is pleasure in making important?

The pleasure in handling is inherent in human nature for good reason: It predisposes us to be tool users and makers. We have this very unusual dexterous hand with an opposable thumb and flexible, sensitive fingers. Our Australopithecus predecessors made crude stone tools two and a half million years ago. I hypothesize that if their descendants didn’t like (or were unable) to use their hands, they would not have survived and prospered as well as those who did.

The earliest hunter-gatherers had to be makers of everything they needed for their lives. In The Raw and the Cooked, distinguished French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote about a point at which our early human ancestors began to transform nature into culture. They took raw food and cooked it and made pots from clay. Later, they wove raw fibers into cloth. Art historian Herbert Cole elaborated on Lévi-Strauss’s ideas and talked about the raw, the cooked, and the gourmet. He said that sometimes just cooking food is not enough: You want to make it special. You don’t just simply make a clay pot—on special occasions, you incise or paint it with stripes and other geometrics. In Early Rock Art of the American West, my coauthor, Ekkehart Malotki, and I cite the making of cupules (small cup-shaped marks pounded into rock surfaces) two hundred thousand years ago at Sai Island in present-day Sudan as the first evidence of artifying (to date). But it is quite likely that there was body decorating, as well as dancing and singing (in other words, making ordinary body movements and gestures and vocal sounds extraordinary) much earlier. These behaviors don’t leave traces behind, but they seem quite natural to our species as they occur very early and easily in small children.

You have emphasized in your work other aspects of human nature that derive from our remote hunter-gatherer past.

In Art and Intimacy, I sorted the emotional needs of all humans into five categories that originated in our hunter-gatherer ancestors. The first I called hands-on competence (the ability to do the things required of men and women in society), which of course for hundreds of thousands of years required using one’s hands. Another I called elaboration, or making special. Meeting these needs is as important today as it was back then. Modern-day makers might choose to create pottery or sew clothing not because they have to but because they feel the urge, even need, to do it. The fact that it feels good to make things with our hands harkens back to our hunter-gatherer nature, which lives on in our psychology.

In a traditional society, hands-on competence, learning to do what is expected of adult men and women, is what growing up is about.

Yes. Girls were taught to prepare food, boys to make animal traps and fishing nets. In some groups, only females or only males made pots or wove baskets. All these skills were acquired as a matter of course by watching and interacting with others, and the skills were within the capability of all normal people. Today, although they have the “freedom” to choose their own paths to satisfying work, not all young people can figure out their own place in the larger world, where it is difficult to acquire the skills that will bring the money and prestige that have become the measure of success. In traditional societies, a material object that one made was tangible evidence that one had accomplished something, even though it might not have been “the best.” Participation was the important thing.

Besides hands-on competence and elaboration, what are the other three needs of our hunter-gatherer nature that you identified?

Mutuality, belonging, and meaning. Mutuality is having a close, intimate relationship with another person or people, beginning from the first moment after birth and continuing throughout a lifetime. Belonging is being an unquestioned part of a like-minded group. Believing what other people in your group believe (what we call “myths” when we encounter them in tribal societies) provides assurance that life has meaning and purpose. And making special (or elaborating) demonstrates that one cares about what one has made and reinforces the beliefs that give life meaning.

Ellen’s multidisciplinary approach to the study of art and evolution is reflected in the carefully organized reference materials in her office.

If making with our hands and making special are part of our inheritance from our hunter-gatherer ancestors, what do you think happens when we are not satisfying those needs?

In small-scale societies, life as lived satisfies the five fundamental needs—there is a kind of unity or wholeness of belief and behavior that is shared by everyone. In modern pluralistic societies that extol the individual, we have more opportunities and choices, but we forfeit the security of being in a group that supports our beliefs and accepts who we are. Each person has to find their own way of satisfying the basic emotional needs that were laid down in the way of life of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. I think a lot of modern people’s ennui, or feelings of depression or meaninglessness, comes from the fact that although our physical and material needs are met, we are not satisfying these psychological or emotional needs of our hunter-gatherer nature.

Today, we model consuming more than making (and replacing rather than repairing). What happens if we don’t model making for our children?

Young children inherently want to use their hands. First, they learn to pick up, then to place down, to drop, to hammer. Then they start manipulating and playing with everything they encounter. Later, they begin (often spontaneously, without being taught) to dance, sing, dress up and play make-believe, perform, and so forth. When they are young and in preschool or kindergarten, many are encouraged to make things—paper snowflakes and jack-o’-lanterns, clay bookends—but as they get older, making things isn’t usually considered a priority. If we don’t foster making, many children’s natural drive to do it will atrophy. In premodern societies, the infant’s and child’s pleasure in handling and then using objects evolved naturally into making them—implements, vessels, homes, regalia. Today, for many reasons, we buy things rather than make them. Although this is convenient, we forfeit our evolved birthright of being makers, and may not even discover it.

Do you think making and making special could actually be less important today than they were in the past?

A child’s impulse to handle and make and the tradition among individuals and societies to make significant things and occasions special are ongoing. Though making may not be important in a practical sense anymore, I don’t think it is less critical today than it was a quarter of a million years ago. I have said that the psychological losses of not artifying can be likened to a vitamin deficiency. You may not know that you have it, but once you learn that you do and rectify it, you feel so much better.

I believe that using my hands to make things and generally being competent with my hands are essential to my happiness. I would even say essential to my emotional wellness.

All makers seem to feel that way and wonder why everyone else doesn’t. Maybe everyone finds some essential thing they can do. I play the piano. My son likes to work on his car and to rehab houses. My daughter makes quilts. My grandfather was a cabinetmaker. There are people who sing all the time. They might wonder why other people don’t. I would guess that everyone has the need to make the ordinary extraordinary, to artify in some way. I have a few friends who, when they send something in a real envelope (rare these days), artify the envelope with colored pencils and fancy lettering, framing the address with scrolls or other designs. Artifying includes setting a table with flowers or, if you’re going to a party, wearing something special.

I’ve met a lot of people, especially women, who know that their handwork is important to them on a deep level but play it down or trivialize it. Or, even worse, people around them trivialize it.

In a society that considers the arts to be something to do in your spare time, it is hard to justify doing it—especially when others consider it only a pastime, a “frill.” That’s why finding even two or three like-minded (and -handed) makers can be inspirational. Also, if it is pointed out that working for money is a very recent development, at least people might be able to see themselves as being in a line of makers and elaborators that goes back two hundred thousand years or more. At one time, making was crucial to our individual and species survival and, certainly compared to passively ingesting entertainment, probably still is. Neglecting the fundamental emotional needs of humans may result in seriously dysfunctional individuals and societies.

What do you think will happen if we continue to allow machines to replace our hands for so many tasks? Beyond not making our own clothes, some of us don’t even chop vegetables anymore but instead buy them precut. And, of course, cars that drive themselves are imminent.

Evolution works so slowly that it is hard to point out the deleterious effects of not making, since so many people seem to get along well without doing it. Although a few people eat a paleo diet, those who don’t are still surviving. The rave concerts with audience participation are a kind of ceremonial ritual full of artifications—one could say it is an atavistic attempt to get back to those satisfactions. My own opinion is that we are neglecting at our peril what neuroscience has revealed are “right hemisphere” functions (paying attention to our surroundings, empathy, intuition, metaphor, emotional expression, aesthetic decisions and appreciation, and so forth—aspects of the arts that we have no words for because the right hemisphere lacks “propositional” or “rational” language). We have made a world that requires “left hemisphere” skills (analysis, detachment, sequential argument) in order to survive.

It sounds depressing to say that we are psychologically and emotionally really badly off, especially in modern society, because we neglect those five basic needs. We are rich in material comforts that our ancestors did not have but poor in the emotional satisfactions they had by virtue of their lifestyle. It is a big mismatch. Simply using our hands—or dancing and singing and other artifying—is not going to stop that. However, in individual lives, and in the lives of the children we raise or can influence, I think we can be aware that active making, and making special, contributes to satisfactions (fulfillment of basic emotional needs) that cannot come any other way.