Witchcraft vs. Witch-craze

When we talk about witchcraft we must distinguish between witchcraft itself and the witch-craze—the historical repression of witches during one particular period in modern history.

Witchcraft (or sorcery) has always existed; the witch-craze was a distinctly modern historical phenomenon—comparable to Nazism or Stalinism—in which multitudes of human beings (mostly women) were subjected to grievous torture by their fellows (mostly men) and condemned to horrible deaths for “crimes” which today we consider wholly fanciful. Nor were they condemned by the rabble, but rather by the most intellectual, learned, and religious men of their day.

A useful theory of the witch-craze is given by Marvin Harris in his remarkable book Cows, Pigs, Wars and Witches: The Riddles of Culture. Harris points out that the systematic persecution of people for sorcery is a relatively recent phenomenon. People who claimed to be sorcerers and magicians always existed; so did people who believed in their powers. But only during one rather specific period in history—the fourteenth through the seventeenth centuries—were the powers of Church and state brought to bear in order to exterminate so-called witches. During this period an estimated half-million people—some chroniclers say more—were executed for witchcraft. (Gerald Gardner, the noted twentieth-century English witch, says nine million in his Witchcraft Today.)

Why did the persecution of witches become so virulent at this time? In the early Middle Ages the Church officially maintained that the flight of witches through the air was an illusion produced by the Devil; in the early modern period, the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries, the Church’s official line on this changed, and it became heretical not to believe that the flight of witches did actually take place. Hundreds of thousands of people (perhaps millions)—80 percent of whom were women—were burned for “confessing” (under hideous torture) what five hundred years before had been declared an impossibility: namely that they flew through the air to Sabbats where they met the Devil, had intercourse with him, and swore their undying allegiance to him.

Marvin Harris explains the witch-craze from a socioeconomic point of view. As medieval society broke down, the Church was increasingly threatened by heretical sects and peasant rebellions. In order to keep its control over the populace, the Church shifted the blame for bad economic and social conditions from itself (and the nobility) to women who flew through the air, blighted crops, killed babies, brought plagues against animals, and generally wreaked havoc on the body politic. The witch-craze became a means of relieving the ruling class and the Church of blame and making scapegoats instead of the poor, the disenfranchised, the female. The Church thus established itself as the seeming guardian of the people against the forces of evil—just at a time when people were beginning to doubt the Church’s magic and perhaps to wonder why they needed the Church at all.

Torture was used to procure scapegoat after scapegoat, and so society “weathered” the transition from the medieval to the modern world with the power of the ruling class pretty much intact.

When, in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries, witches were no longer needed as scapegoats, the figure of the witch receded into storybook, poem, and myth—only to be resurrected in the early twentieth century by an educated middle and upper class that was bored with conventional religions and sought a revival of antique (and antic) gods.

Today, we understand the witch as an archetype, as a psychological embodiment, and it seems almost impossible to imagine the bloodshed and torture that went on in the name of witchcraft.

Clearly, there are pagan beliefs still present in our modern world, and none of them inspires in us a lust for torturing and incinerating our neighbors. But lest we make the mistake of assuming that our ancestors were less intelligent than we (a concept known as Urdummheit, or primeval stupidity), let us think of all the things we would kill our neighbors for. The witch is not dead; she is merely hibernating. And witch-hunting itself is hardly dead; it is merely waiting to be born again under a different name.

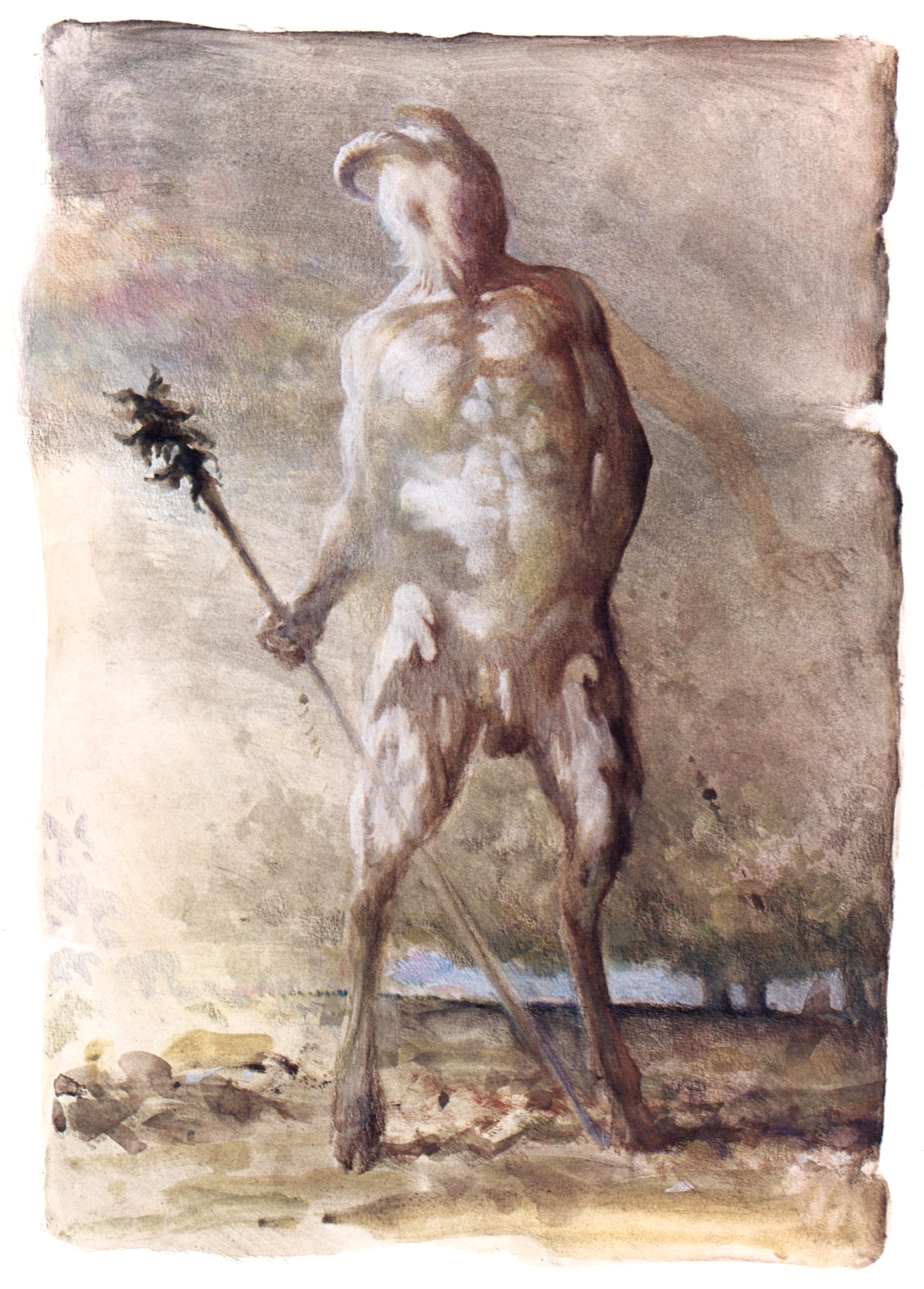

To the Horned God

The extinct stars

look down

on the centuries

of the horned God.

From the dark recesses

of the Caverne

des Trois Frères

in Ariège,

to the horned Moses

of Michelangelo,

in Rome,

from the Bull of Minos

& his leaping dancers

poised on the horns

of the dilemma …

From Pan

laughing & fucking

& making light

of all devils,

to the Devil himself,

the Man in Black,

conjured by

the lusts of Christians …

From Osiris

of the upper &

lower kingdoms,

to the Minotaur of azure Crete

& his lost labyrinth …

From Cernunnos

to Satan—

God of dark desires—

what a decline

in horny Gods!

O for a goat to dance with!

O for a circle of witches

skyclad under the horned moon!

Outside my window

the hunters are shooting deer.

Thus has your worship sunk.

O God with horns,

come back.

O unicorn in captivity,

come lead us out

of our willful darkness!

Come skewer the sun

with your pointed horns,

& make the cave, the skull, the pelvic arch

once more

a place of light.