SKULL AND BONES SOCIETY

FOUNDED: 1832

STATUS: Active

EXCLUSIVITY FACTOR: High—only fifteen students are initiated each year.

SECRECY FACTOR: Medium—members’ names are public, but their meetings and some of their rituals are not.

THREAT FACTOR: Potentially high—the members often go on to hold positions in the highest echelons of power.

QUIRK FACTOR: Low. Nothing quirky about preppies.

HISTORY AND BACKGROUND

Long before Harvard spawned Facebook, there was a much more exclusive Ivy League social network: Yale’s legendary Skull and Bones Society. It was founded by two seniors, Alphonso Taft (father of the 27th US president) and valedictorian William Huntington Russell in 1832. Russell was disgruntled about not receiving an invitation to the prestigious academic secret society Phi Beta Kappa, so he retaliated by forming Skull and Bones, which grew to be just as esteemed as Phi Beta Kappa and even more mysterious.

Skull and Bones pays obeisance to Eulogia, the goddess of eloquence—which is ironic, because members are forbidden to speak about the club and are even instructed to get up and leave the room if the society comes up in conversation. Legend has it that Eulogia took her place in the pantheon in 322 B.C., and she returned in a kind of second coming on the occasion of the society’s inception. This is why the number 322 appears in the society’s skull and crossbones logo.

The society is known informally as “Bones,” and members are known as “Bonesmen” (which is better than “Boners”). Just fifteen Bonesmen are chosen from every senior class, but out of this relatively small group has come a disproportionately large percentage of the world’s most powerful leaders. Over the years, Bones has included presidents, cabinet officers, spies, Supreme Court justices, and captains of industry.

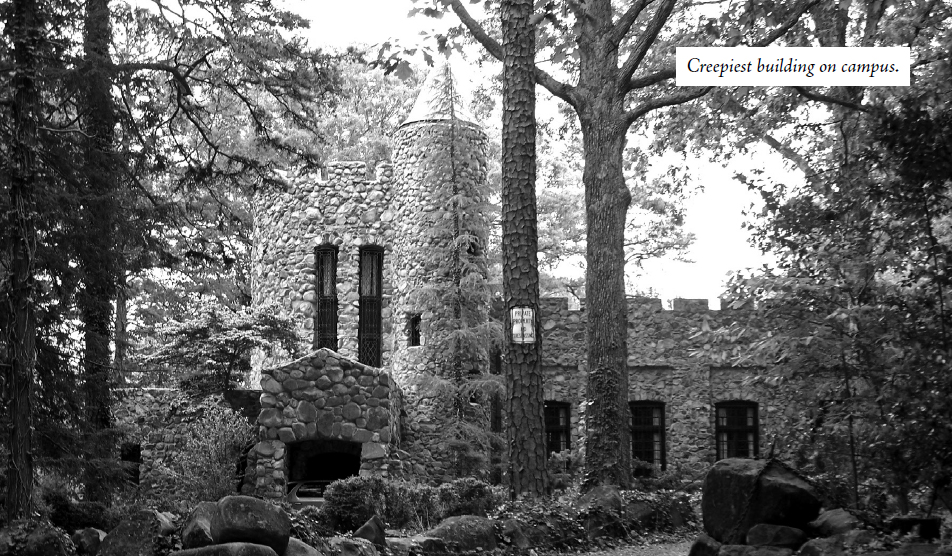

Indeed, the mystique surrounding Skull and Bones sets it apart from Yale’s other secret societies, among them being Scroll and Key, Wolf ’s Head, Book and Snake, Mace and Chain, and Berzelius. Landed societies, like Bones, have buildings on campus. Their headquarters is a brown sandstone mausoleum known as the Tomb: a crypt-like, windowless structure that is strictly off-limits to non-members.

The most private room in the building is known as the Inner Temple, or Room 322. Behind the locked iron door is a case holding a skeleton that the Bonesmen call Madame Pompadour. Along with her remains, the case contains the society’s cherished manuscripts, including the secrecy oath and instructions for conducting an initiation—a ritual in which they are said to use human remains.

There certainly is no shortage of bones inside of the Tomb. It is decorated with dozens of dangling skeletons and skulls and other macabre relics. Chiseled on the walls are German and Latin phrases such as Whether poor or rich, all are equal in death.

But while rich and poor may be equal in death, that’s not necessarily so in life. The wealth, privilege, and power enjoyed by Bonesmen has sparked many conspiracy theories about the group. Skull and Bones has been implicated in everything from the creation of the nuclear bomb to the Kennedy assassination.

MEMBERSHIP REQUIREMENTS

Picture this: It’s springtime of your junior year, and you’re taking a nighttime stroll around campus. Suddenly, you are approached by a group of masked seniors who force you into a black limousine and offer to take you back to their tomb. Would you accept the invitation? Many Yalies would, happily. This process of “tapping” is how Skull and Bones singles out potential members.

“Tap Night” works a bit like the Sorting Hat at Hogwarts in the Harry Potter books—it’s when juniors are invited to join the society that is the best fit for them, with Skull and Bones being the most prestigious of the bunch (though disturbingly similar to Slytherin in some ways). Years ago, the tapper would order the tappee to “Go to your room,” and then extend the formal invitation to join the club in the privacy of the tappee’s dorm room. If the tappee accepted the invitation—and he almost always did—he was promptly inducted into the society that very day.

Tap Night is a slightly more raucous affair these days, with contenders for Skull and Bones and Yale’s other secret societies running around campus in Halloween-like costumes. It may be preceded by interviews and “pre-taps,” giving the tappers and the tappees a chance to test the waters before committing to a society.

So who gets tapped for Skull and Bones? Historically, young men from the richest and most powerful families were prize picks. Relatives of Bonesmen also got preference. Even in the late 1960s, when many of Yale’s other senior societies had adopted more progressive practices, Bones was still a boys’ club with a reputation of choosing the same kinds of people, year after year. In an article in the 1968 Yale yearbook, Lanny Davis, a 1967 Yale graduate and a secret society member who would go on to become a White House special counsel in the Clinton Administration, described their selection process as follows:

If the society had a good year, this is what the “ideal” group will consist of: a football captain; a Chairman of the Yale Daily News; a conspicuous radical; a Whiffenpoof; a swimming captain; a notorious drunk with a 94 average; a film-maker; a political columnist; a religious group leader; a Chairman of the Lit; a foreigner; a ladies’ man with two motorcycles; an ex-service man; a negro, if there are enough to go around; a guy nobody else in the group had heard of, ever.

Today, the Skull and Bones roster is not quite so predictable, nor is it as dependent on class and blood ties. It is still elite and selective, but with a focus on inducting student leaders from various backgrounds. In 1991, they voted to allow women in (by a narrow margin), and recent groups of induct-ees are usually divided equally between men and women and almost always include Hispanic, Asian, African American, and LGBT students. What these members have in common is that they seem poised to go on to positions of great power, which is the purpose behind this secret society.

INSIDE SKULL AND BONES

Bonesmen meet in the Tomb two evenings per week, as they have done since the dawn of the order. They spend one of the nights socializing and the other debating cultural and political affairs. But details of what goes on behind Tomb doors are unknown to most outsiders. Because members take an oath of secrecy, persuading one to speak to the press is tough. Alexandra Robbins, author of the Skull and Bones exposé Secrets of the Tomb, says that the majority of the Bonesmen she contacted refused to speak to her, and some even harassed and threatened her. However, she did manage to glean this information about their initiation ritual, which apparently features an interesting group of characters:

There is a devil, a Don Quixote and a Pope who has one foot sheathed in a white monogrammed slipper resting on a stone skull. The initiates are led into the room one at a time. And once an initiate is inside, the Bones-men shriek at him. Finally, the Bonesman is shoved to his knees in front of Don Quixote as the shrieking crowd falls silent. And Don Quixote lifts his sword and taps the Bonesman on his left shoulder and says, “By order of our order, I dub thee knight of Eulogia.”

Journalist Ron Rosenbaum wasn’t permitted such access, so he hid out on the roof of a neighboring building and surreptitiously videotaped a nocturnal initiation ceremony in the Tomb’s courtyard. He described it thus: “A woman holds a knife and pretends to slash the throat of another person lying down before them, and there’s screaming and yelling at the neophytes.”

Rosenbaum has been obsessed with Bones ever since his days at Yale as a classmate to George W. Bush. He longed to get inside their clubhouse. “I had passed it all the time,” says Rosenbaum. “During the initiation rites, you could hear strange cries and whispers coming from the Skull and Bones tomb.”

Whatever is going on in there, it was once considered very unladylike. “There were rituals that some women would find offensive,” says a Bonesman from the 1960s, who refused to elaborate. “Some [alumni] wanted to fight to make sure those traditions didn’t have to change.” Could he be referring to the longstanding rumor that Bonesmen masturbate inside of coffins? Or something even more sinister?

Though members of Skull and Bones refuse to speak openly about their society to outsiders, they are required to reveal their innermost secrets to fellow initiates. In a ritual called “connubial bliss,” the brand new Bones-men would gather round the fireplace and recount their entire sexual and romantic histories. Today, this ritual has evolved from an X-rated affair to a PG-13 party where each new member delivers an oral autobiography, a time-consuming event meant to forge friendship. Either way, knowing all of each other’s deepest, darkest secrets is a kind of protection.

Bonesmen know each other by code names. Long Devil is assigned to the tallest member; Boaz (short for Beelzebub) is bestowed upon anyone who is a varsity football captain. Other names are drawn from literature (Hamlet, Uncle Remus), from religion, and from myth. The name Magog is traditionally assigned to the incoming Bonesman with the most sexual experience, and Gog goes to the new member with the least. William Howard Taft and Robert Taft were Magogs. So was George H. W. Bush, difficult as that may be to imagine—apparently, his undergrad antics would have had Barbara clutching her pearls. Their son George W. was not assigned a name, but invited to choose one. Nothing came to mind, so he was given the name “Temporary,” which he never bothered to replace.

George W.’s grandfather, Prescott Bush, made a more permanent contribution to Skull and Bones lore. Bones and other Yale societies have a reputation for stealing from each other or from campus buildings. They have a charming name for this thievery: “crooking.” During the first World War, prankster Prescott Bush and some of his fellow Bonesmen are believed to have “crooked” the grave of the great Apache warrior Geronimo. His skull is reportedly kept in a glass case by the front door of the Tomb.

More human remains decorate the interior walls: skeletons, skulls, and other ghoulish ornaments, along with portraits of distinguished members. To continue with the Harry Potter comparisons, it sounds rather like Hogwarts meets haunted house, though a recent infiltrator said the inside of the Tomb looked “something like a German beer hall.”

Members of other societies who have managed to break into the Tomb describe a tunnel leading to a chamber with a coffin. There is also a room with candles, a chopping-block, and a basin with two carved skeletal figures leaning over it full of red liquid. They say the place is infested with bats. In the garden, a statue of a knight looms over barbeque grills. Adding to the Goth-frat atmosphere is the stolen gravestone of Elihu Yale, the eighteenth-century merchant that the University is named for, displayed in a glass case in a room with purple walls. A 1980s Bonesman described the Tomb as “a place that used to be really nice but felt kind of beat up, lived in.”

The decaying grandeur extends to Deer Island, a Bones-owned island on the St. Lawrence River. Robbins describes the place as follows:

The forty-acre retreat is intended to give Bonesmen an opportunity to “get together and rekindle old friendships.” A century ago the island sported tennis courts and its softball fields were surrounded by rhubarb plants and gooseberry bushes. Catboats waited on the lake. Stewards catered elegant meals. But although each new Skull and Bones member still visits Deer Island, the place leaves something to be desired. “Now it is just a bunch of burned-out stone buildings,” a patriarch sighs. “It’s basically ruins.” Another Bonesman says that to call the island “rustic” would be to glorify it. “It’s a dump, but it’s beautiful.”