Honshū, the main island of Japan, is largely mountainous and heavily forested [MAB].

Honshū – The Heart of Japan

Honshū is the largest of Japan’s islands and is generally considered to be the mainland of Japan. Honshū straddles a number of different climatic zones, producing great natural diversity from north to south and from east to west, while its mountainous spine divides the Sea of Japan coast from the Pacific coast and generates local weather effects. These regional and local climatic patterns in turn affect the distribution of various types of forest and so also the distribution of a range of other organisms.

Shintō is Japan’s own animistic religion, and shrines can be found throughout the country [MAB].

The mountains held sacred and home to many deities of the Shintō pantheon, were taboo until barely 150 years ago. Even today, religious taboos combined with long-established culture prevent development on the mountain slopes, with the exception of forestry. While visitors may regard this as a missed opportunity, these taboos are grounded in common sense. Today, typhoon-related flooding and erosion, earthquakes and landslides often lay waste to housing situated at the base of hillsides. If occupied, the mountain slopes would be the scene of great annual devastation and disaster. One consequence of this attitude is the immense crowding of human settlement, as dwellings, industrial buildings and transport infrastructure, including rural roads, highways, railways and elevated bullet-train tracks, are restricted to the lowlands. The impact of the large human population is at its greatest here in Honshū, and the rapid pace of development since 1945 has been at its most extreme in the scarce lowland areas.

Much of Japan’s human population is concentrated in Honshū. Although it is only the seventh largest island in the world, it is the second most populous large island after Java. Of Japan’s nearly 127 million people, 103 million (in 2005), more than 81 percent, live in Honshū. Tōkyō, Japan’s capital, houses more than 13 million people, while the greater metropolitan area spreads across three prefectures and is estimated to be home to more than 36 million people. Recent development has overwhelmed the coastal lowlands that were once used almost exclusively for agriculture. Farming, people and industry are now all crowded into the same narrow space spreading from the foot of the mountains to the sea. Inland, much of the rail-and-road network burrows and tunnels its way through the mountains from coast to coast, while settlements and agriculture are crowded into narrow valleys. Thus, the scene is one of contrasts: small coastal fishing communities cheek-by-jowl with major shipping ports, oil refineries and industrial complexes; small rural communities at odds with vast urban sprawl; and narrow tracts of farmland among steep-sided, densely forested mountains. At first sight there seems little room for nature.

Historically, Japan’s mountains, such as these in the Shirakami Sanchi World Heritage Site, were both sacred and taboo [PUDQ].

Honshū’s northern region, Tōhoku, is extensive, occupying 18 percent of the island, yet has a mere 8 percent of the human population. It is extremely rugged, with a backbone formed by the longest mountain chain in Japan, the Ōu Mountains, and includes Mt Iwate as its highest peak at 2,038 m. Tōhoku experiences severe winters, as the seasonal winds from the Asian mainland bring heavy snow to the Sea of Japan coast and the mountains. In contrast, in the rain shadow farther east along the Pacific Coast, Sanriku is cold and dry.

The Shirakami Mountains, in northwest Tōhoku, are home to extensive native beech forest, a host of azaleas and other flowering shrubs, along with Asiatic Black Bears and, perhaps, the last Black Woodpeckers in Honshū. Farther inland, the crater lakes of Towada, Tazawa and Inawashiro, and the highland regions of Hachimantai and Urabandai are scenic highlights. To the north of the region’s capital of Sendai, the wetlands of Izu-numa and Uchi-numa are not to be missed. These two lakes host one of the most spectacular gatherings of wintering geese one could hope to see in Asia. These are predominantly Greater White-fronted Geese but lesser numbers of other species occur, sometimes including rarities. Together with an array of other waterfowl, including swans and both dabbling and diving ducks, each winter the lakes host many tens of thousands of birds, making the cacophony and sight as they depart at dawn and arrive at dusk truly sensational.

Mountains and forests provide vital water catchment, make up the largest areas of wild habitats in the country, and support tremendous biodiversity [left MAB; right Silver Dragon Plant KuM].

Lake Towada and the Oirase River in northern Honshū are reminders of Japan’s natural bounty [top right AOTA; others MOEN].

Izu-numa and Uchi-numa wetlands host a spectacular gathering of wintering waterfowl [YM].

Farther south, the Kantō Region, while the smallest of Japan’s seven main regions and occupying just 8 percent of the country, is home to the nation’s capital, Tōkyō, and many other cities, too, so that as many as 40 million people, close to a third of the nation’s total, live there. Enormous Tōkyō Bay was once home to vast numbers of migratory waterfowl and shorebirds, but today only tiny fragments of semi-natural wetland survive and only small numbers of birds pass through. However, the capital’s wetland reserves (such as Kasai Marine Park, also known as Kasai Rinkai Kōen) and its urban parks (such as Meiji Shrine) are renowned among birdwatchers. To find more wildlife, though, it is necessary to travel to the western outskirts of the city. Yet, within sight of the capital are regions where Japanese Badger, Japanese Giant Flying Squirrel and the endemic Copper Pheasant can all be found. Meanwhile, to the east, in the reedbeds along the Tone River, are Green Pheasants and rare species such as Marsh Grassbird and Japanese Reed Bunting.

To the south of the Tōhoku and west of the Kantō regions, the Chūbu Region spans both coasts. It is home to Mt Fuji and the Japan Alps (see p. 242) and hence is the source of much of the region’s water, as many major rivers arise here, some flowing west to the Sea of Japan, others east to the Pacific. It is also home to Sado, the island home of Crested Ibis; the Noto Peninsula and, for nature photographers, the single most famous site of all, Jigokudani in Nagano Prefecture, the winter home of the world-famous Snow Monkeys (see p. 253). While Chūbu’s Sea of Japan coast is known as Snow Country and the Japan Alps have what are among the heaviest snowfalls in the world, the Pacific Ocean coast experiences mild winters and hot summers. It is not surprising, therefore, that the highland regions of Karuizawa, Tateshina and the Fuji Five Lakes are popular summer retreats for residents of the Kantō Region and perennially popular with birdwatchers and wildlife photographers. Even this region of Japan has endemic species of plants and insects, for example the delightful Japanese Luehdorfia, or Gifu Butterfly.

To the west of the Chūbu Region lies the Kansai Region, home to the famous industrial cities of Ōsaka and Kōbe, the second largest metropolitan area in Japan, and the cultural capitals of Kyōto and Nara. There are mountain ranges to the north, the Chūgoku Mountains and Tanba Highlands, and to the south the Kii Mountains, separated by a broad lowland zone which to the west faces the sheltered Setonaikai, Japan’s Inland Sea, with its rather Mediterranean Climate. The Kansai Region is also home to one of Japan’s three most beautiful views, that of the pine-clad coastal spit at Amanohashidate in Miyazu Bay, in northern Kyōto Prefecture.

Urban parks, such as here at Meiji Shrine in Tōkyō, are havens of nature for city dwellers [PUDQ].

Many endemic and near-endemic species, such as Marsh Grassbird (left) and Japanese Reed Bunting (right), survive even within sight of the nation’s capital [BOTH KT].

Crested Ibis forage in natural wetlands and wet rice fields. Their grey seasonal breeding plumage is unique among ibises. In flight they reveal the uniquely named (toki-iro) colour of their flight feathers, named after the Japanese name for the bird [BOTH MAB].

Sado is the largest island in the Sea of Japan and home to the reintroduced population of the Crested Ibis [MAB].

From space, one feature above all others in Japan is striking – enormous Lake Biwa. Not only is it Japan’s largest lake, it is also one of the oldest surviving lakes on earth, dating back some four million years. Lake Biwa’s long uninterrupted history of isolation has allowed the evolution of numerous endemic species of fish in the lake. There are also numerous endemic freshwater snails and bivalves, alongside many other species that are more widespread natives. In winter, the lake attracts many thousands of migratory waterfowl. Unfortunately, the lake’s biodiversity has suffered through the introduction of alien and invasive fish species, including Largemouth Bass and Bluegill, which prey heavily on native species.

Farther west from Lake Biwa, where the Maruyama River meanders its way north of the city of Toyooka and the community of Kinosaki into the Sea of Japan, is the home of Oriental Stork. Here, brave efforts have been made to breed in captivity and then release this endangered species that was once exterminated as a breeding bird in Japan. This almost crane-sized stork is a dramatic sight, and it can now be seen easily in captivity and in the wild at the Hyōgo Park of the Oriental White Stork, and often, along with many other species, at the Hachigorō Toshima Wetlands.

The westernmost region of Honshū is known as Chūgoku. To its south lies Shikoku and to its west Kyūshū. Here the Chūgoku Mountains are aligned east–west, as are those of Shikoku; between the two lies the island-studded Inland Sea. Since ancient times the Inland Sea has been a crucial route of communication; religion, culture and goods moved this way into the country via what was essentially a marine section at the eastern end of the ancient Silk Road. Before the more recent development of Japan’s railway network, the only efficient means of transporting goods through the region was via this inland sea. The distinctive forests of this region support both Japanese Black Pine and Japanese Red Pine and the many islands protected in the Setonaikai National Park have an attractive flora which includes numerous species of azalea. The marine environment here supports both the strange, living fossil known as Japanese Horseshoe Crab and Indo-Pacific Finless Porpoise. Human communities here are centred on major river mouths or harbours, restricted by the general lack of flat land.

Key natural features of the Chūgoku region are the extraordinary Tottori sand dunes facing the Sea of Japan. These dunes are wind-driven marine sands. In a country of otherwise lush greenery, this strangely desert-like landscape is home to some very specialized plants, such as Asiatic Sand Sedge, Beach Silvertop and Beach Vitex. Protected as part of the San’in Kaigan (Coast) National Park, and also recognized as the San’in Kaigan Geopark, the area includes diverse, distinctive and beautiful coastal scenery and geology, incorporating coastal crags and dunes, caves, extensive areas of columnar basaltic lava and inland mountains spanning 120 km from east to west and covering an area of 2,458 km2 – one of the largest geoparks in Japan. The area has both aesthetic and scientific value, particularly because the land forms here tell the story of the early development of the Japanese Islands with formations dating from the period of the Sea of Japan’s creation.

Farther along the Sea of Japan coast to the west the twin lakes of Shinji and Nakaumi are important sites for wintering waterfowl, such as the highly vocal Bewick’s Swan, and the dapper Tufted Duck. To the east of the lakes is the dramatic Mt Daisen massif, presenting steep walls when viewed from the south or north, with diverse flora ranging from beech groves and Japanese Yew to alpine flowers. Offshore to the north are the numerous Oki Islands, washed by the warm Tsushima Current, which have a mild climate and even warm-water corals. The forests of Chūgoku are home to a wide range of Japan’s resident and summer-visiting avian species, while the cold montane rivers host the endemic Japanese Giant Salamander (p. 267).

Hiroshima, the largest city of the region, has been entirely reconstructed since it was devastated by an atomic bomb on 6 August 1945. It has now, with its peace park and memorial museum, become a major tourist destination, as has nearby Miyajima, with its freestanding Torii gate out in the bay, and Itsukushima Shrine that are partly inundated at high tide. Inland from Hiroshima lies the Nishi-Chūgoku Sanchi Quasi National Park with its not-to-be-missed Sandan-kyŌ (Three Level Gorge), a national special place of scenic beauty. The area abounds with hiking trails, and the beautifully forested river gorge can be explored on foot to admire the various waterfalls and the Siebold’s Beech, Japanese Zelkova and Japanese Horse Chestnut groves. Here you can watch Brown Dipper, Common Kingfisher and other birds beside the water, and can explore the area by kayak and by boat.

Amanohashidate, in Miyazu Bay, is considered one of the three most beautiful classic views of the country along with Matsushima and Itsukushima [MAB].

The strange Japanese Horseshoe Crab is considered a kind of living fossil [KHCM].

The desert-like dunes along the Sea of Japan coast of Tottori Prefecture are a rarity in Japan [MAB].

Enormous Lake Biwa is Japan’s largest and oldest lake [MAB].

Bewick’s Swan migrates to spend the winter in western Japan [MAB].

Endemic Japanese Giant Salamanders live in cold montane rivers [FR].

The enormous Torii gate marks the entrance to the beautiful Itsukushima Shrine [MAB].

The karst landscape of Akiyoshidai Quasi National Park is the largest in Japan [MAB].

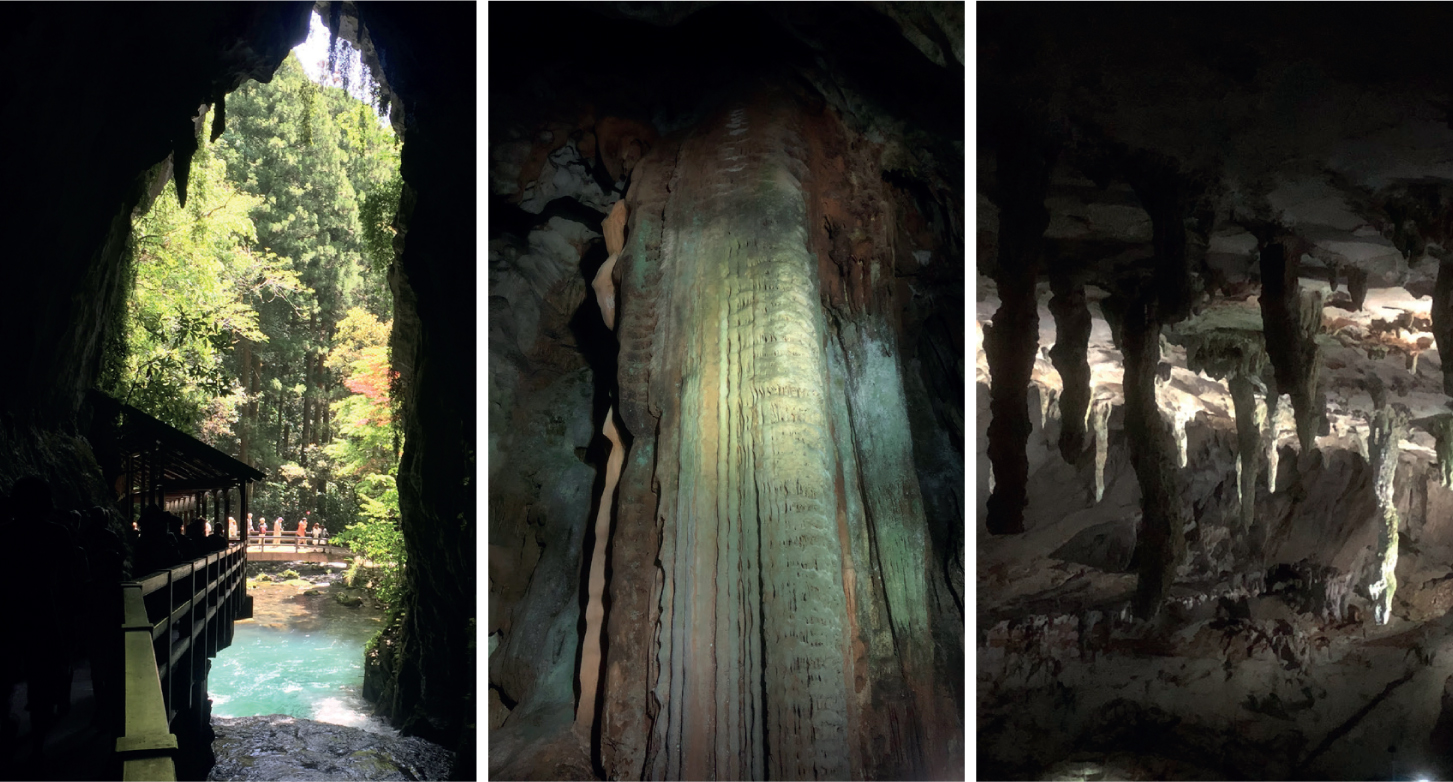

The large cave complex of Akiyoshidō lies hidden beneath the Akiyoshidai landscape [ALL MAB].

In far western Chūgoku, in Yamaguchi Prefecture, between the delightfully sleepy, historical town of Hagi and the bustling port city of Shimonoseki, lies the extraordinary Akiyoshidai Quasi National Park. In Hagi, once capital of the Mori Clan – one of the most powerful clans during Japan’s feudal age – one can explore the well-preserved former samurai district, delightful Tōkōji and Daishōin temples and its distinctive Hagiyaki pottery. Shimonoseki, the prefectural capital, is nicknamed locally as the Fugu (Pufferfish) Capital because it is the largest market for species such as Tiger Pufferfish in Japan.

The famous Three Level Gorge or Sandan-kyō [BOTH HIPR]

Akiyoshidai provides a window into some fascinating aspects of non-volcanic geology in Japan. Akiyoshidai has the largest karst landscape in the country, stretching 17 km from east to west and about 8 km from north to south. Its limestone plateau with greenstone basement was formed about 350 Mya and is the remnant of extensive coral reefs. The uplifted landscape, formed from permo-carboniferous limestone and now exposed to air and rainfall, has been eroded1, resulting in the unique complex karst landscape, with rugged limestone pinnacles and numerous dolines2, or sinkholes. Where water has penetrated the ground through these sinkholes, it has carved out runnels and hidden streams, and eventually an immense cave complex, Akiyoshidō. This cave complex, the largest in East Asia, comes complete with an underground river and several waterfalls. The intricate structures in the cave include numerous stalactites and stalagmites, columns like organ pipes, a 15-m lace curtain of rock known as Kogane Bashira, and the extraordinary Hyakumaizara, the sinter-terrace-like disc-shaped formations or rim-stones resembling miniature flooded rice paddies. Everything has been formed over eons, as water has first eroded the limestone, then deposited it again, drip by drip, in wonderful forms and shapes. The limestone here has yielded many fossils, including those of corals, brachiopods and bryozoans. Various invertebrates have evolved in these dark, damp conditions, giving the caves a unique fauna. In some sections of the caves several thousand of as many as six species of bat roost. While the cave complex extends over more than 10 km, a readily accessible and easily walked 1-km trail traverses an engrossing section and, with a stable underground temperature of 17°C, the caves are not only an enjoyable diversion throughout the year, but also one of the most fascinating geological excursions in Japan.

Japan’s Southern Squirrels

Blakiston’s Line, the great biogeographical divide in northern Japan, separates a multitude of species from one another, including Japan’s various squirrels. North of the line, across the Tsugaru Strait in Hokkaidō, occur Eurasian Red Squirrel, Siberian Flying Squirrel and Siberian Chipmunk (as described on p. 188). South of the line, all are replaced by different endemic species and joined by a well-established introduced species.

The squirrels share an elongate, slightly pointed face with protruding black eyes and long, prominent whiskers. They have long fore limbs and particularly dexterous fingers with which they can grasp and manipulate their food. They are mostly arboreal, and strong limbs and sharp claws mean that they are as comfortable climbing or descending head down as when moving head up.

In Central Japan, occupying essentially the same niches as in Hokkaidō, we have Japanese Squirrel and Japanese Flying Squirrel, but larger than all others there is also Japanese Giant Flying Squirrel. The interloper here is Pallas’s Squirrel, introduced from Taiwan and designated an Invasive Alien Species by law in 2005, and occasionally you may bump into a chipmunk introduced from peninsular Korea.

Japanese Squirrel is a sister species to Eurasian Red Squirrel and is endemic to Central Japan. It is wide-ranging within Japan, but may have become extinct in Kyūshū. It favours mixed woodlands with plenty of deciduous trees and it occurs also in parks and large gardens. Smaller and lighter than its more northerly relative, Japanese Squirrel weighs 150–310 g and measures just 16–22 cm in head-and-body length, with a tail 13–17 cm long. Its coat is reddish-brown in summer, turning greyish-brown in winter, and it has a pure white belly and a white tip to its tail. Its short ears grow tufts in winter, but never so long as those of Eurasian Red Squirrel.

The introduced Pallas’s Squirrel, at 20–22 cm long plus a tail of 17–20 cm, is similar in size to Japan’s endemic squirrel, but is heavier at about 360 g. It has dark grey-brown fur on its upperparts, with golden or grey tips to the hairs lending a brindled appearance. Its underside is greyish-brown, not white as in the sympatric Japanese Squirrel. It has short, untufted ears and a long (almost as long as the body) very bushy tail, usually held aligned with its body. In its natural range it occurs from northeast India to Taiwan, from where it was introduced to Japan in the 1930s; it has thrived locally in Japan since its first release.

So far, it remains confined to pockets of forested habitat in the warmer southern parts of central and western Honshū and Kyūshū – including parts of Kamakura, on Izu Ōshima, in Ōsaka, or in Himeji. It can be locally common in dark, shady broadleaf evergreen forests, where it feeds on a range of buds, flowers, leaves, bark, fruits, nuts and insects. Although usually a solitary species foraging mostly in the trees, it will visit feeders, but it appears not to occur in those habitats favoured by the endemic Japanese Squirrel or to compete with it, nor is it regarded as a pest.

Male Pallas’s Squirrels occupy non-exclusive home ranges of up to 3 ha; these overlap with those of several females (each with a much smaller range of approximately 0·5 ha). Breeding occurs once a year in autumn, when they use tree cavities in which to nest, or construct a large spherical drey of twigs in the fork of a tree, where the females produce litters of one or two young.

The endemic Japanese Giant Flying Squirrel (left) and Japanese Flying Squirrel (right) are both confined to the forests of the main islands south of Hokkaidō [BOTH MM].

Whereas the Eurasian Red Squirrel occurs in Hokkaidō, the endemic Japanese Squirrel is found only south of Blakiston’s Line [MM].

The introduced Pallas’s Squirrel is currently restricted to warmer forested regions in Honshū and Kyūshū [MM].

With a somewhat similar geographical range to that of Japanese Squirrel, Japanese Flying Squirrel is also confined to Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū but, instead of occurring in lowland broadleaf forests, it favours montane and subalpine forests. This small, pale grey-brown nocturnal flying squirrel is endemic to Japan. In winter it is largely pale grey on the upperparts but with a pale brown back in summer. The underparts, from the chin and throat to the lower belly, are creamy white. It has a rounded face, with distinctively enormous, bulbous black eyes appearing disproportionately large for the head size, and has short rounded ears. The tail is long, flattened and about two-thirds of the body length. When settled, the species appears to have a ruffled flap of skin or fur along its flanks; this is the retracted flying membrane, which extends between fore and hind limbs. It weighs 150–220 g and measures 14–20 cm in length, with a tail 10–14 cm long.

Occurring in native forests from the mid montane zone to the subalpine zone, Japanese Flying Squirrel uses natural tree cavities, including disused woodpecker holes, as breeding sites and daytime roost sites. At dusk, the squirrels emerge from their roosting sites, climb up the trunk of the tree and then launch into a glide, using their flying membrane, down to another tree and so off around their territory in search of their food, which consists of leaves, buds, seeds and fruits of trees and some fungi. They breed once or twice each year, the females giving give birth to 3–5 young in each litter.

Dwarfing Japanese Flying Squirrel is Japanese Giant Flying Squirrel. One of a number of giant flying squirrels across Asia, this one is endemic to the lowland and montane forests of Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū. This large, cat-sized flying squirrel is brown on the upperparts (pale brown in the north, dark brown in the south) and pale greyish-white on the underparts. It has an oval face, more pointed and hence more squirrel-like than those of the two smaller flying squirrel species in Japan, with smaller eyes and slightly longer, more pointed ears. The face pattern is distinctive, being slightly paler on the forehead between the eyes, and with pale crescents extending from the crown, in front of each ear, onto the cheeks. The tail is long, flattened and about three-quarters of the body length. During gliding, the flying membrane is extended between the fore and hind limbs, as with the two smaller species, but also between the neck and the fore limbs and between the hind limbs and the tail. It weighs a hefty 700–1,000 g, and measures 34–48 cm in length with an additional 28–41 cm of tail.

Nocturnal and arboreal, this is a mostly solitary creature, although you may occasionally see it in family groups. It ranges from the lowlands to the montane and even subalpine zones in native primary mixed deciduous forests and mature secondary forest, and occurs also in conifer plantations. Japanese Giant Flying Squirrel uses natural tree cavities or nestboxes as breeding sites and daytime roost sites. Some of its finest habitats are the large old trees left standing around hillside temples or shrines. There the trees are left to mature and the wildlife is left in peace.

At dusk, as with other flying squirrels, individuals emerge from their roosting sites, climb up the trunk of the tree and then launch themselves, stretching out their arms and legs, and glide off to explore their territory in search of food. This giant flying squirrel’s diet includes the leaves, buds, flowers, seeds and nuts of deciduous broadleaf trees, and because it occasionally eats tree bark it can cause damage, especially in conifer plantations. Cat-sized and silent as a cat burglar, it is usually visible only as a dark shadow flitting between the trees. When ‘flying’ at night, its pale belly and the white undersides of its ‘wing’ flaps make it appear quite ghostly and ethereal as it passes silently among the treetops.

Japanese Giant Flying Squirrels are territorial: males have larger home ranges (up to 3 ha) than those of females (up to 1–1·5 ha). They breed twice a year, mating in winter and spring, the females giving birth to two litters of 1–4 young in spring and autumn after a gestation period of about 75 days. They survive for up to 14 years in captivity, and probably to about ten years in the wild.

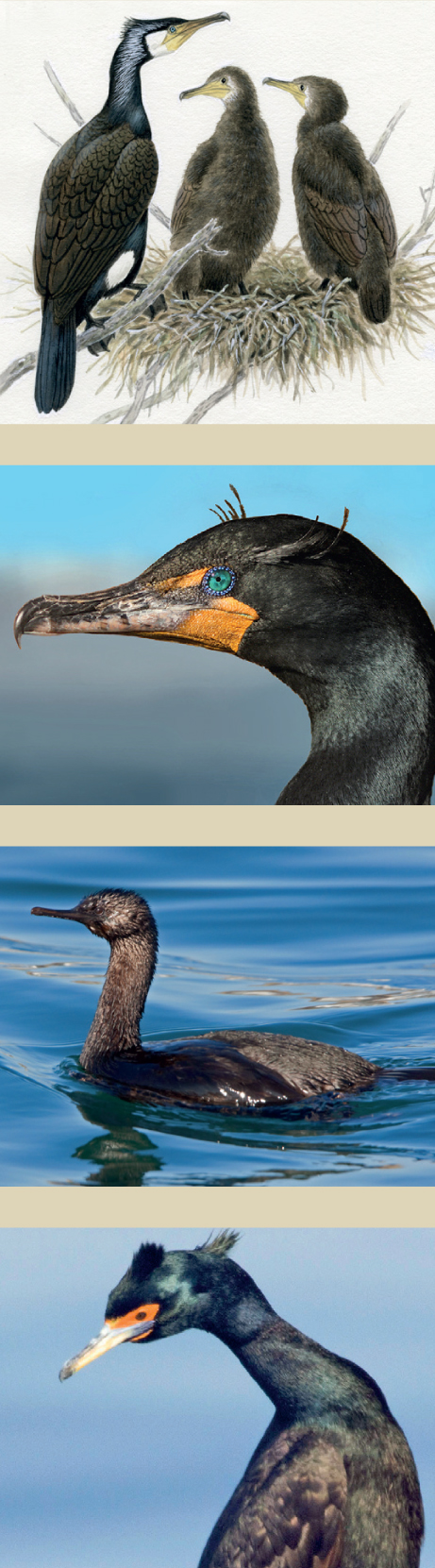

Cormorants and Ukai

With Japan’s coastline measuring 29,751 km (greater even than that of Australia: 25,760 km) and with so many islands, it should come as no surprise that Japan hosts several species of cormorant. Great Cormorant breeds throughout the main islands; Temminck’s Cormorant is resident around northern coasts and winters around much of the rest of the country; Pelagic Cormorant breeds locally around Hokkaidō and winters widely farther south; and rarest of the four is Red-faced Cormorant, which, at the southwesternmost limit of its North Pacific range, occurs locally in southeast Hokkaidō.

The coastal cormorant of Japan is Temminck’s Cormorant, which resembles closely Great Cormorant of freshwater areas, and greatly dwarfs the much more slender Pelagic Cormorant. These cormorants dive for their prey and kick their enormous webbed feet for propulsion, rather like an underwater paddle steamer.

It is not the cormorants themselves that are surprising but what people do with them! During the summer, on several rivers in Honshū, fishermen can be seen out in pursuit of Sweetfish, not with rod and reel but with cormorant, leash, boat and brazier.

The practice, known as Ukai, has certainly continued for more than 1,300 years on Gifu Prefecture’s Nagara River. There, in both Gifu and Seki cities, the master fishers are entitled – Imperial Fishermen of the Royal Household Agency. The practice occurs also on more than ten other rivers in western Japan, including on the Uji River south of Kyōto. The fishermen go out at night not because cormorants are nocturnal but because, by using a burning brazier on their fishing boats, they can draw fish up to the surface, where the leashed cormorants are able to catch them easily. Rings around the necks of the cormorants prevent them from swallowing the fish completely, so that, once a cormorant has caught a Sweetfish, the master fisherman reins it in, removes the fish from its gullet and sends the bird back to work, giving it a break every now and then and a reward. Most surprising of all is that the fishermen do not use the local Great Cormorants, which are so widespread and common in Honshū, but instead they use Temminck’s Cormorants from the coast.

Great Cormorants occur widely in Japan [YaM]; Temminck’s Cormorant is essentially a bird of the coast, where it nests on crags and cliffs. [JW]; Pelagic Cormorant in northern Japan [MC]; the range of Red-faced Cormorant just reaches Japan in southeast Hokkaidō [KT].

Temminck’s Cormorants are used for Ukai – catching Sweetfish – at night [GPTF].

Pheasants – Copper and Green

Both of Japan’s pheasants are endemic, and one, Green Pheasant, is the national bird known as Kiji. This somewhat secretive metallic-green bird favours woodland and farmland edge habitats and may occasionally be seen wandering out in fields, although it prefers to remain hidden in tall grasses, revealing itself by its rather hoarse, loud “ko-kyok” call. It can be found in the lowlands of all three main islands of Japan, but not Hokkaidō.

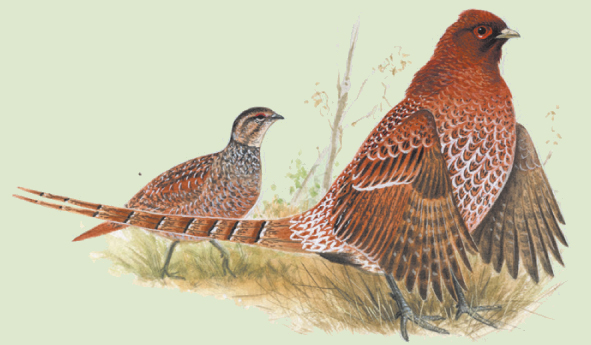

Copper Pheasant [YaM]

The second species, Copper Pheasant, is one of the most sought-after Japanese endemics among visiting birdwatchers. In contrast to the Green, the Copper is a bird of montane forests. There are grisly folk tales from northern Honshū of these birds, known as Yamadori1 in Japanese, playing pranks on newcomers to the mountains by creating terrific crashing sounds and mimicking severed heads rolling down from the mountains over the snow. In reality the most likely sign of a Copper Pheasant is the occasional cast feather on the forest floor, or the whirring sound of rapid wingbeats as a bird flees deep cover. Should you be fortunate enough to find a long, drooping coppery-brown tail feather, you will have found a real jewel. Not only are those feathers exquisite, but they are also said to be endowed with magical qualities. These beautiful feathers have transverse bands or nodes and special properties. A feather of 13 nodes is said to be proof against evil spirits, while folk tales say that a pheasant with such a feather may trick people. And at night Yamadori feathers are said to phosphoresce and frighten people away. The human residents of Hida (now in Gifu Prefecture) believed that very old Yamadori emitted light when they flew, making them visible on moonless nights.

Folk tales apart, the Yamadori is an extremely attractive bird unique to Japan, and, as its English name suggests, it is brightly copper-coloured. If you are willing to ignore the ghost stories, you can look for this shy, secretive and elusive bird in broadleaf and mixed coniferous-and-broadleaf forests in montane regions of Japan up to the subalpine zone in Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū.

There is an aura about Copper Pheasant and it has nothing to do with the supposedly magical and mystical nodes of its tail. Naturalists who visit Japan invariably rank this among the top five species they dream of seeing.

It is a bird of consummate camouflage, as copper as the leaves, as silent in its movements as the first tendrils of spring, and rarely heard calling. Like other pheasants, Copper Pheasant is not overly fond of flying unless it can glide downhill. So, look for it as it runs uphill to escape between the trees. If it should take off, it will do so with an explosive burst of speed, leaving the undergrowth like a springing deer, and clattering through the trees, only then to glide downslope and away from its pursuer.

The endemic Green Pheasant is Japan’s national bird [AK].

Male Copper Pheasants drum in display and show off their long tail plumes [TK].

The elusive Chinese Bamboo Partridge is far more frequently heard than seen [TK].

Copper Pheasant is best detected when the males are drumming during late winter and spring. As a Copper Pheasant strolls its favourite forest paths, its long tail tips fall slightly apart and, sometimes, gently brush the ground. To drum, the male pauses, stands tall and still atop a fallen log, or rock, or on the forest floor, and beats his short, broad wings so rapidly that they emit a strange muffled thrumming like a bull-roarer. As he drums, he shows off the full length of his 125-cm long tail drooping down behind him. With his raspberry red eye-wattle engorged, he is a magnificent bird, especially when, with a blurring whirr of his wings, he produces that loud “phhhrrrrp” again.

The whirring phhhrrrrp sound is made by the rush of air over the stiff wing quills, and forms an important part of spring courtship. Although it is quite a strong sound and far-carrying, it can easily be overlooked because it is so low, much like muffled thunder, or a distant truck tipping its load of earth. Count yourself fortunate if you hear one, let alone see one.

Once very common, even abundant, with nearly a million shot each year, this sedentary and generally solitary bird has declined under the onslaught. Although the shooting of females has been illegal since 1976, this highly sought-after bird is still a difficult one to find.

The highly vocal Chinese Bamboo Partridge, a distant relative of the pheasants, is widespread in the southern half of the country. Despite its loud and frequent calls, however, it is typically elusive in dense undergrowth.

There are several subspecies of Copper Pheasant, including a white-rumped subspecies in Kyūshū [TK].

1 In the avian context Yamadori means mountain bird. In a botanical context, however, the same word means the taking of small trees or plants from the mountains and is, in essence, the origin of bonsai.

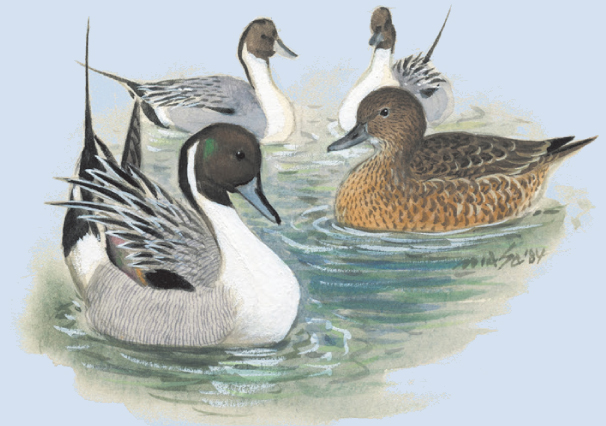

Wintering Waterfowl

While sea-ducks (see p. 118) are at home in the surf, in harbours and along rocky coasts, another 25 or more species of dabbling and diving ducks, geese and swans make the freshwater and brackish habitats of Japan amazing magnets for wintering waterfowl. These habitats include lakes, marshes, lagoons, rivers and river estuaries. The waterfowl arrive each autumn from Siberia to spend the winter in the relative warmth of Japan’s temperate climate, feeding, and forming pairs, in readiness for their return northwards in spring to breed.

Northern Pintail [YaM]

Piping flocks of Northern Pintail occur in their thousands at many rivers and lakes around Japan, and these are joined by many other species, including Eurasian Wigeon, Mallard and Eurasian Teal. For waterfowl aficionados it will be the distinctively Asian Falcated Duck and Baikal Teal [VU] that will be the most enticing.

Skeins of Greater White-fronted Goose and Tundra Bean Goose [VU] migrate, by way of the Kuril Islands or via Sakhalin, first to Hokkaidō and then to Honshū. Their numbers exceed 100,000 birds, and they spend several months each winter in commuting between traditional night-time roosting sites. Major roosting sites for them include the Izu-numa and Uchi-numa lakes, in Miyagi Prefecture, and Miyajima-numa, in west Hokkaidō, from where they commute to their feeding grounds on fields, where they glean the waste left over from the grain harvest or graze the grasses along the strips between the fields. Rarer geese, especially Cackling Goose [CR], Snow Goose and Lesser White-fronted Goose, are sometimes among them.

Wetland habitats draw enormous numbers of wintering waterfowl from northeast Asia [MAB].

Greater White-fronted Geese extend their autumn migration over several weeks, pausing along the way at important feeding and roosting sites such as at Miyajima-numa, in western Hokkaidō [MAB].

Less numerous than the ducks, and even larger than the geese, are the ‘Angels of Winter’. On a blizzard of wings, Bewick’s and Whooper Swans migrate south across the Sea of Okhotsk, alighting with much calling and whooping, as they find their resting spots at lagoons along the coast of Hokkaidō. Family members call and greet one another as they settle in with their flock to feed and recover from their long flight. Some may move on. All of the Bewick’s Swans will pass on to milder regions of Honshū, especially in the north and at sites along the Sea of Japan coast, but many of the larger-bodied Whooper Swans will remain in Hokkaidō. Cruising amid the spiralling steam from thermal springs, they appear ethereal, and mystical, true Angels of Winter (see also p. 176).

Migrating Whooper Swans arriving in Hokkaidō for the winter [WaM].

The Asian Snow Goose population is recovering and many now winter in northern Honshū [MAB].

Once rare in Japan, Cackling Goose numbers are recovering rapidly [WaM].

Baikal Teal is among the prettiest of Asian duck species [TK].

Male Falcated Duck sports full breeding plumage during winter in Japan [MAB].

Mandarin – the Hooded Love Bird of the East

Appearance

Almost like phantoms, or moving shadows, silent shapes jump into the air, take wing and flee along a densely wooded river valley and are soon out of sight upstream. Mandarin Duck is a shy shade-loving bird, but catch a clear glimpse of one and its colours shout – Oshidori.

Mandarin Duck [YaM]

Secretive and difficult to observe in their secluded summer habitat along mountain streams and at wooded lakesides, it is from autumn onwards, when Japan’s forest colours are brilliant enough to match even the male Mandarin’s gorgeous plumage, that they become much easier to watch. At this time Mandarins gather in increasingly conspicuous numbers at secluded lakes, even on moats and shaded city-park ponds in the lowlands of Japan. These wintering congregations are flighty, full of activity and prone to rising en masse to form a whirling airborne flock that flashes orange. It is then, too, that avian predators, such as Northern Goshawk, drive Mandarin Duck flocks into the air and pick off their prey.

Only when the males sail out into full sunlight do their colours and patterns come into their own, and then they are splendid. Some consider them the most gorgeously plumed of all waterfowl. Each aspect of the Mandarin’s plumage has been honed by competitive attention to detail. The elongate, creamy eye stripes, like designer spectacles, contrast with the dark forehead, the long orange and green crest and the orange ruff. At first sight, the stubby pink bill with its yellowish-white tip seems out of place – until it is shown in vivid contrast when it is tucked back against the dark maroon of the breast, as the male rocks back on his orange feet and thrusts out his chest in display. A double necklace of contrasting narrow white and broad black bands dramatically divides the maroon neck and chest from the bird’s finely vermiculated orange flanks. The mantle and wings are resplendent in purplish-black, white and orange, while the lower chest and belly are of the purest white.

The Mandarin male appears as a duck in designer clothing. In the shady woodland habitat, even the seemingly gaudy colours of the male are surprisingly camouflaged, and the dappled greys and browns of the females virtually disappear against the browns of the woodland floor and in the rippled shadows on the water.

Male (right) and female (left) Mandarin Duck [FT]

For all the intricate details of the Mandarin’s colours and its pattern, it is a singular, unique feather that defines this bird. None of the more than 10,000 other avian species on earth shares such an oddity. The drake Mandarin is the only one to carry such an instantly recognizable and highly modified wing feather, and it serves a singular purpose. This immensely asymmetric feather, a single tertial on each wing, has a greatly enlarged vane which stands proud on its strongly arched rachis, while the vane below is narrow. The upper portion of the vane stands conspicuously tall, like a raised sail, and is brightly orange, whereas the portion of the vane below is mostly hidden and is as deep and as iridescent a blue as a Mallard’s speculum.

Behaviour

The twin biological requisites of survival and reproduction have, through sexual and natural selection, driven avian mating systems that coincidentally enchant and delight the human eye and ear. That male birds sing, display, posture and carry great adornments, to show off to their mates, is widely known and commonplace from the diminutive wren to the enormous peacock, and to the Mandarin’s tertial feather. The popular press, meanwhile, may mistakenly describe these males as being showy, flashy or gaudy, as if they are revealing some kind of terribly chauvinistic character flaw that they should grow out of, but, in reality, the males are being driven by a biological imperative: mate choice by the female has driven the development of these plumage characteristics and behaviour. Likewise, the same press may anthropomorphize further and describe the females as drab or dull and as hoodwinked into maternal care by their lazy mates, all the while ignoring the evolutionary selective pressures that have honed their very different and very successful sexual strategies over many millions of years.

If this bird seems to wear designer clothing, then its movements, too, seem to have been choreographed for the catwalk, mingling swagger and swish with bravado and allure. Meanwhile, his suitress is clad in a cryptic blend of subtle greys, browns and cream, with a delicate pair of whitish spectacles. She has all the understated elegance borne of the confidence of being in charge.

Male Mandarins pursue the subtly plumed females and engage in a range of behaviours, including chest-puffing courtship [FT].

Mandarin Ducks prefer the shadiest areas of rivers, ponds and lakes. They like those places where overhanging trees cast shade on the water below, where they can stand on a low branch over the water or on a stump at the water’s edge, or where they can forage safely on the ground, looking for seeds and nuts, especially acorns. On the water, the Mandarin males swim leisurely back and forth, each holding its orange ‘sails’ high above its back like a samurai’s pennant. Their capes and ruffs are spread for the greatest effect, and they puff out their chests as they try to outdo each other and, at the same time, attract the attention of the trim grey-plumed females nearby. It is she, not he, who chooses, while her potential mates must endlessly display and joust for her attentions.

Each male Mandarin Duck spends many hours during the course of the winter and spring in showing off his finery in the hope that a female may select him as her mate. The males gather and posture, raising their crests, fluffing out their ruffs, puffing up their chests. They swim together, suddenly surging through the water, showing off their strengths; meanwhile, the cryptic females are watching and listening, spending their time in selecting and choosing.

Courtship and Breeding

By spring, when the wintering flocks are breaking up, the females will have made their choices, the pairs will have formed and mating will have started. Eventually, the pairs fly off to their chosen rivers and begin carving out their territories. Each pair will seek out a mature deciduous tree in which there is a large cavity, which perhaps began life as a woodpecker’s hole or as the crack left by a storm-smashed limb. If the cavity suits, and once the pair has mated several times, the female will lay her clutch of up to 14 eggs in the seclusion of the tree hole. For two or three more weeks during April or May, the male remains nearby, perhaps to come out of seclusion to protect his mate should a predator appear, but soon he must leave or risk drawing unnecessary attention to the breeding site.

The tiny yellowish-brown chicks emerge as mere wisps of animated down, and soon they must learn the avian equivalent of base-jumping. Long before they have matured, the mother calls her chicks forth from the safety of their nest cavity, and there is only one way for them to leave. They are clad in just their natal down and have yet to develop their feathers, so they completely lack the plumes which they need for flight. They must therefore scrabble to the lip of their high-rise home, sometimes as much as 18 m above the ground, then take the plunge and jump from the nest down to the woodland floor. Like tiny parachuting fluff-balls, legs and webs spread and tiny wings fluttering, they fall to bounce and land in the leaf litter far below. Then, they must make their way hurriedly to their mother and the safety of water, which may be more than a kilometre away from the nest tree. They rely on their own cryptic plumage, and their mother’s continual state of alert, for their protection during the weeks when they grow. If startled or disturbed by a predator when they are very young, they dive and flee to hide beneath the riverbank, and when older they skitter and skim away across the water surface following their mother to safety. When young they are at risk from predatory fish and from mammals such as martens and Tanuki, and as adults they are at risk from attack by forest-dwelling birds of prey such as Northern Goshawk and Japanese Hawk-Eagle.

Meanwhile, the brightly coloured drakes have left their mates, their breeding territories and their offspring behind, in order to find seclusion where they can moult. The males now drop their bright plumes in favour of a more cryptic eclipse plumage. As do many other waterfowl, they drop all their primary wing feathers at once, and so they become temporarily flightless. While the males are moulting, the females are tending to their broods. Once autumn returns, the males emerge from their eclipse phase into their bright nuptial plumage and, once more, it is time for them to compete for the opportunity to mate.

Mythology

The English name ‘Mandarin’ for this delightful duck is perhaps derived from the fact that its distinctive orange ruff and orange sail-like wing feathers brought to mind the orange robes of the high officials in the former Chinese imperial civil service. Its scientific generic name, Aix, is derived from an Ancient Greek word, and its use attributed to Aristotle for an unknown duck, while its scientific specific name, galericulata, means ‘the hooded one’. The hooded one’s Japanese name, Oshidori, written in ancient pictograms, carries within it the meaning of love bird, and in numerous folk tales this species epitomizes both conjugal love and marital fidelity.

The long-entrenched belief that male and female Oshidori consort together throughout the year, much as do cranes, has led to the Mandarin having a powerful symbolic role in the art and literature of Japan. Mandarin is revered here as a symbol of conjugal love and affection, and of marital bliss and fidelity, and its image appears in a myriad of forms. Happily married couples in Japan are known as Oshidori hūhu, meaning Oshidori couple.

Folk tales are told of the remarkable bond between the male and female, and one of these was transcribed into English by that great interpreter of things Japanese, Lafcadio Hearn. Hearn relates, at some length, the heartbreaking tale of a falconer and hunter by the name of Sonjō, who lived long ago in the northern province of Mutsu, and who destroyed the bond that ties a male and a female Mandarin together.

But not all tales told of the Mandarin are sad, and another tells a story of affection and gratitude. A drake Mandarin, captured alive and kept in a cage by a wealthy man, was pining and refusing to eat. A kind-hearted maidservant, working in the wealthy man’s household, persuaded the servant responsible for its care that a bird so devoted to its mate would pine until death if kept alone. Out of compassion the servant took her advice and released it. When the owner discovered the Mandarin’s absence, however, he immediately suspected the servant and began treating him cruelly. Distressed by the cruelty she saw him suffering, and feeling partly responsible having given him the advice, the maid was drawn to him and, in time, the couple fell in love. With the power wielded by the wealthy in those days, the master sentenced the young lovers to death, without trial, for causing the loss of his valued pet. As luck would have it, and before the sentence could be carried out, two messengers arrived from the provincial governor carrying the news that the sentenced offenders were to be taken before the governor.

The journey to the provincial capital was long, and the young lovers, overcome by fatigue, became increasingly unable to keep up with the messengers until eventually they realized that they had been left behind and were lost. Eventually, they came upon a rustic hut and there the exhausted lovers spent the night. To both of them, in their dreams, the messengers of the day before returned and explained that they were, in fact, the Mandarin which they had released and his mate. Knowing of their fate at the hands of the master, they had returned to rescue them. When the lovers awoke the next morning the messengers had gone, but instead, before the hut, was a pair of Mandarin Ducks, who bowed to them and then flew away into the forest. The young couple fled, found employment in another province and were married. They had saved the magical union of the Oshidori and, in return, the avian messengers had made their union possible; it was a union that was to become as strong and enduring as that of the birds.

A female Mandarin Duck emerges with her brood after breeding in a large tree cavity [FT].

The Intelligence of Crows

Crows in Japan are ubiquitous, and, before you ask, that crow you are watching, however big you think it is, is not a Northern Raven, although it is often mistaken for one. Two species are abundant, the more slender-billed Oriental Crow and the massive-beaked Japanese Crow (known also as Large-billed Crow and before that, the Jungle Crow). Both are widespread and both can be found wherever there are people – including in rural villages, major conurbations, coastal fishing communities and narrow-valley agricultural areas in the mountains. They differ in their size and behaviour, but most noticeably in their head and bill shapes.

Japanese Crow [YaM]

One question arises repeatedly: ‘What can we do about the crow problem?’ The answer is to rethink the question. Crows are not the problem; it is what humans do that has precipitated the problems.

Crows, birds in the Corvidae family, occur around the world. There are various branches of the family, some wearing the familiar mournful black raiment of Northern Raven, Oriental Crow and Japanese Crow. Others are less obviously crows, examples being Eurasian Jay with its dazzling blue wing patch, Spotted Nutcracker with its spangled plumage, and the various tropical jays of Central and South America, which tend to be more specialized in their habitat and food requirements, too. Some of these family members are at home only in forest, while others, more flexible in their lifestyle, are comfortable close to human habitation. A small and select group of crows, generally the black ones of the genus Corvus, are out-and-out opportunists, finding food, nesting material and nesting sites wherever they can. Opportunists are like that. It is no good complaining about them; the only answer is not to put temptation their way.

Opportunism takes many forms, but, if a bird has that nature, then consider its options. Put yourself in a crow’s feathers. Would you, given the choice, fly a long way from your night-time roost, and spend all day searching for food on the off chance of finding enough when all the time you know that just around the corner someone is putting out a heap of food? Of course you wouldn’t; you’d think of an extra hour asleep, nip around the corner, grab the grub and go back to a cosy resting site. I am unashamedly anthropomorphizing, but that is pretty much what certain members of the crow tribe will do. I do not recall any country other than perhaps India that has so many crows as Japan.

In most countries crows tend to be cheeky, pugnacious and quick to take advantage, but generally they are not very common. They gather at roost sites to spend the night in the safety of large numbers but, come the morning, they disperse in search of food. Crows have found agriculture to their liking. After all, wherever there are domestic animals, there are fields with lots of droppings and these serve to attract insects, earthworms and the like – all food for hungry crows, which are just continuing their tradition of following herds of wild ruminants. Many crows are happy with carrion, too, so wherever animals die, or where larger animals waste their food, they are quick to take advantage and sneak in for a free treat. They gather also where nature provides a bounty. For example, a salmon river dotted with dying fish after the spawning will attract crows. Where a storm has tossed up flotsam from the sea, crows will scour the tideline in search of a free meal of dead fish or the like.

Japanese Crow is both scavenger and predator. Its massive bill gives it access to garbage and tree cavities, allowing it to feast on urban waste and nesting birds [KT].

Crows, such as Oriental Crow, are among the most widespread of birds in Japan [MM].

Northern Raven, a rare winter visitor mostly to eastern Hokkaidō, is known to indulge in play behaviour [MaH].

Crows are renowned for taking advantage of the urban landscape, we leave an almost unlimited amount of food available for them [MaH].

We tend to forget, with our natural predisposition for anthropomorphizing animals, that other species do not do things because they are good or bad, or out of spite, they do them simply because they are motivated by natural instinctive goals – food, a resting place, a breeding place; so far as we know, they make no value judgements.

Crows are not attracted to cities in themselves. What attracts them is a supply of good food, good nesting sites and good roosting sites. Anywhere that supplies all three is going to attract crows, and enable them to breed and produce more crows looking to meet the same needs. From a crow’s perspective, modern cities provide valuable resources. In the main, cities are more important in winter, especially in temperate parts of the world. Cities are major energy-consumers and thus major waste-producers. Much of that waste is in the form of heat, so cities now serve as significant heat islands. Not surprisingly, birds are aware of this, and crows in particular take advantage of winter roosting sites that are a few degrees warmer than elsewhere. While human commuters are returning to their suburban homes, the crows are literally flocking into our cities to sleep.

In other countries the crows, as morning arrives, fly out of the city in search of food, but one thing distinguishes Japan from many countries that have crows and that is the extraordinary, and messy, means of garbage disposal – piling up garbage in plastic bags out in the street for collection. Garbage bags are flimsy and a person does not need to be armed with anything more than a determined finger to be able to poke a hole in one. Any creature armed with teeth and claws, such as a rat, or armed with a meat-cleaver of a beak, such as Japanese Crow, must just think that it has died and gone to heaven. All that garbage, much of it containing edible waste, is literally dumped on the streets and often overnight! Talk about temptation. In Hokkaidō, some citizens feel proud that they carefully cover the heap of plastic bags with a mesh net but, while this may stop garbage from rolling or blowing away, it certainly cannot stop a determined crow wielding a powerful beak. Temptation is lying there in a heap, and a crow has a degree of intelligence that it cannot fail to use in such circumstances.

The so-called crow problem is not really a crow problem, it is a people problem. Step one: dispose of organic waste and non-organic waste separately (preferably composting the former). Step two: change the method of depositing garbage so that flimsy plastic bags of rubbish do not lie out in the street. Other countries use permanent bins that are animal-proof and, not surprisingly, where they are used crows are rarely seen foraging in the streets. Crows appear to be at an extremely and unnaturally high level of abundance in Japan because of the enormous volume of garbage produced in both urban and rural areas by people. There are so many open garbage dumps that crows benefit greatly from our wasteful way of life. Until we change our ways, crows will remain abundant.

Crows are not merely abundant, they are intelligent, and their capacity to solve problems is widely known. Their ability to take advantage of our infrastructure and waste is less well known, but crows in Japan are known to gather wire coat-hangers (the type used by dry cleaners) with which to build their nests. They are also known to use passing traffic to crush hard nuts for them!1 Japanese crows, like gulls, are not averse to flying up with shellfish, sea-urchins and other hard items, and then dropping them from a height on to a hard surface so as to break them open for the food inside. In several Japanese cities, Oriental Crows are aware of traffic lights and traffic movement and take advantage of the traffic to crush nuts placed or dropped on to the road, and then make use of the traffic lights and the pedestrian crossing to allow them to retrieve the nuts without being run over!2

So intelligent are birds that some have time for behaviour that can be described only as play3. The animals involved seem to engage in the behaviour for the fun of it, and among the birds it is the corvids that are considered to exhibit the most complex play behaviour of all.

Northern Raven is the largest corvid that can be found in Japan, and is a rare winter visitor, mainly in the eastern third of Hokkaidō. More common than it once was, it can today be found wintering very locally, most often in the coldest part of the winter during January and February, although sometimes as early as November and until as late as early May. Two areas where ravens may be found in winter are the well-forested, mountainous Akan–Mashū National Park, in central eastern Hokkaidō, and the equally mountainous Shiretoko Peninsula of extreme northeast Hokkaidō. In east Hokkaidō, I have observed ravens engaging in various elements of play behaviour such as I have never seen with Japan’s more commonplace crows, including ‘snow-romping’4. I have watched both individuals and pairs engage in aerial chases, displays, and calling activity, both while flying and while perched among the rocks on the upper slopes of various mountains, and very rarely they also snow-romp, this sometimes even involving several pairs at the same time.

On one particular occasion on 8 February 2000, I watched as three pairs engaged in play. One raven, after landing in the snow, lay on its breast and slid head-forward downhill, apparently ‘sledging’5. Its partner, who was nearby, began by lying sideways to the slope and then rolled over and over downhill. The pair continued sledging and rolling downhill for more than ten metres before flying back upslope to repeat this behaviour. Just minutes later I noted another raven fluttering in deep powder snow as if bathing, while its partner was rolling sideways down the slope nearby. As the latter rolled over repeatedly on to its back, I was able to see its legs in the air, its wings flicking in the snow each time, before it rolled over upright again. A further pair nearby also engaged in similar play behaviour; one member rolled sideways down the slope alone in the snow, and was quickly joined by its partner, which landed on its mate, sat down, and remained there for at least a minute. Meanwhile, one member of the first pair was still sliding head-first down the slope. The three pairs were engaged almost simultaneously in play behaviour in the snow. Rolling ravens disturb powder snow in an erratic manner; ‘sledging’ does, however, leave clear linear tracks downslope in the snow.

Eurasian Jay is a member of the crow family, and in Japan is most frequently found in woodland or forest with distinctive subspecies in the main islands [top, Honshū KT] and in Hokkaidō [bottom MR].

Spotted Nutcracker is a crow-family member found high in the mountains [BOTH MR].

On the Shiretoko Peninsula, at a roost gathering of ravens, I observed a pair preening each other6 while a single individual nearby began pecking at the branch on which it stood. After a few moments, it slipped into a hanging position beneath the branch, holding on with both feet. While upside-down beneath the branch, it let go with one foot, holding on with the other. It then grasped the branch in its beak and let go with both feet so that it hung beneath the branch holding on only with its bill. Finally, after a few tugging motions, as if attempting to break the branch by using its weight, while hanging by its bill, it flew off.

Not far away, in the Akan–Mashū National Park, I watched one of a group of ravens land on the snow slope on the inner rim of the Mashū Caldera. It proceeded to peck out a large chunk of snow crust (larger than its head), and flew off with it in its bill. It was immediately chased by another individual and, after circling for a while, it returned to the same part of the slope and dropped the chunk of snow. Then the raven repeated the process of pecking out snow crust, carrying it into the air, being chased for it, and then dropping the snow crust down on to the slope. On another occasion, I watched a pair among a group of birds that was engaged in aerial pursuits, paired flights, swoops, stalls, and rolling displays. The members of the pair flew towards each other, grasped each other by the beak and descended slowly with their wings and tails spread like two black spiralling parachutes. After several seconds, they disengaged and flew separately. Such apparently playful behaviours are not confined to Northern Raven in Hokkaidō. Oriental Crows in Honshū have been observed to slide down solar panels, and down a children’s slide. Such behaviour may in fact be a means of ‘showing off’ to other individuals and serve as status-enhancing displays of critical importance when establishing pair bonds.

1 A simple internet search for Japanese crows and nuts will reveal numerous videos of this amazing behaviour.

2 It seems that they retrieve only their own nuts. Andrew Davis, who has watched them for hours doing this in Sapporo, has not observed them squabbling with each other, in the middle of the road, over the most recently squashed nut.

3 Play in animals is generally interpreted as any behaviour that seems not to have any direct adaptive advantage.

4 A term coined by Derek Ratcliffe.

5 Carrion Crows are known to indulge in similar sledging behaviour in Europe.

6 This behaviour, known as allopreening, involving two birds preening each other, often involves them in preening each other about the head and neck – areas that are difficult for a bird to preen by itself.

Cuckoos and their Hosts

Eleven species of cuckoo have occurred in Japan, four of which are regular summer visitors: Northern Hawk-Cuckoo, Lesser Cuckoo, Oriental Cuckoo and Common Cuckoo. They breed in wide areas of the country, from Okinawa to Hokkaidō. It is the last species’ call that lends its onomatopoeic name to the whole family. They are all insectivorous birds, feeding largely on the larvae of the Lepidoptera, and they have another, extraordinary feature in common – cuckoldry.

A wide range of native species, including Azure-winged Magpie, Bull-headed Shrike, Oriental Reed Warbler, Eastern Crowned Warbler, Blue-and-white Flycatcher, Japanese Bush Warbler, Asian Stubtail and Olive-backed Pipit, all inadvertently play host to the cuckoos’ eggs. Cuckoos do not spend time on building a nest for themselves or in rearing their own young. Instead they enlist other species to do the hard work, for they are brood parasites. They lay eggs the shells of which are patterned to mimic those of their hosts, hosts which vary among cuckoo species and among individuals. Cuckoo eggs hatch quickly, after only about 12 days of incubation, ahead of the eggs of the host. This gives the young cuckoo a head start for its grisly business of ejecting the host’s eggs or young from the nest. As the young cuckoo grows it outstrips its hosts, so that, by the time the young cuckoos fledge (after about 17–19 days), the small host parents will be feeding a monstrous chick much larger than themselves.

These parasitic cuckoos provide clear evidence of the instinctive nature of migration in passerines. Cuckoo parents are not involved in raising their young and migrate weeks before their offspring. The young cuckoos find their own way to their wintering quarters in Southeast Asia without guidance (other than from their own genetically provided aptitude).

An Oriental Cuckoo fledgling dwarfs its Siberian Rubythroat host [WaM].

Northern Hawk-cuckoos mimic sparrowhawks in shape and plumage [KT].

The smallest cuckoo species in Japan is Lesser Cuckoo [KT].

Common Cuckoos favour woodland edge and grassland habitats [SP].

Oriental Cuckoos closely resemble Common Cuckoos, although their vocalizations are remarkably different [WaM].

Occasional brown-morph females occur [ImM].

1 Limestone, a carbonate sedimentary rock consisting of the skeletal remains of marine organisms, gradually dissolves in water, especially if it is slightly acidic.

2 A doline is a funnel-shaped basin in a karst region.