Southern Nansei Shotō

Japan’s southern extension – the Nansei Shotō – is a separate archipelago in its own right. As described in the preceding chapter, the numerous islands in the warm waters between Japan’s southern main island of Kyūshū and the island of Taiwan differ greatly from the rest of Japan. They are biologically diverse, in fact representing a biodiversity hotspot. The present chapter deals with the southern extension of the Nansei Shotō, including the main island of Okinawa and its subsidiary islands such as the Kerama Islands, and the island of Miyako, which lies farther south and which is now dominated by sugar-cane agriculture; then, as Japan’s last southern outpost, there is the group of islands known as Yaeyama, including in particular the islands of Ishigaki, Iriomote and Yonaguni.

Humpback Whales migrate each year to spend the winter around the Kerama Islands [MAB].

This is Japan’s finger in the subtropical pie. While Hokkaidō freezes for part of each year, Okinawa swelters. A more extreme contrast to subarctic Hokkaidō is hard to imagine. Here are flowers, butterflies and trees more commonly associated with the tropics. White, coral-sand beaches and intense sun add to the image. Offshore, there are coral reefs with myriad colourful fish. One may be lucky and find turtles, too, or even migratory Humpback Whales in the warm waters there. The local vegetation includes ancient-looking living fossils known as Japanese Sago Palms or Sago Cycads, and forests that are lush and evergreen with broad leaves. The wildlife here is very different from that in any other part of Japan, including even the islands just to the north.

These islands have had a fascinatingly chequered history. They have experienced long periods of isolation as islands but, when sea levels have fallen, they have been connected to the continent via Taiwan. At other times, higher sea levels have separated them, not only into the islands that exist now but into even smaller fragments. When the islands were connected, species reached them from Asia and moved between the islands. When the islands have been separated, during the long periods of isolation species have evolved and diverged, and unique endemic forms are the result. New species are still being discovered in this hothouse of biodiversity. A new bird species, Okinawa Rail, was described as recently as the early 1980s.

Zamami, in the Kerama Islands, is part of the Kerama Shotō National Park [OCVB].

The northern hills of Okinawa sustain important forests supporting rich biodiversity [SM].

Endemic frogs: Okinawa Tip-nosed Frog (top left); Holst’s Frog (top right) [BOTH KuM]; Ryukyu Brown Frog (bottom left); and Okinawa Tree Frog (bottom right) [BOTH SM].

The hilly northern third of the main island of Okinawa is known locally as Yambaru, and internationally as having an elevated level of biodiversity even within the biodiversity hotspot of the Japanese archipelago. Yambaru National Park spans the rugged coastline at Cape Hedo, at the north end of the island, Gesashi Bay’s mangrove forest (the largest on the island), and subtropical hill forests. There the typical climax species is the evergreen oak known as Itaji Chinkapin, with occasional stands of the tree ferns known as Brush Pot Trees, on the island’s highest peak, Mt Yonaha (503 m). Despite representing less than 0·1 percent of Japan’s land area, the forests there are home to such rarities as Okinawa Rail, Pryer’s Woodpecker and Yambaru Long-armed Scarab Beetle (Japan’s rarest beetle), and support a quarter of all of Japan’s frog species, including its most beautiful endemic, Okinawa Ishikawa’s Frog [EN]. This is all in an area that makes up less than one tenth of one percent of Japan’s land area.

In 2014, the subtropical archipelago lying just 40 km to the west of Okinawa’s mainland was registered as Japan’s 31st national park, known as Kerama Shotō National Park. The 30 islands of the archipelago belong to the villages of Tokashiki and Zamami. The warm waters around these low hilly islands, surrounded with delightful coastlines of rocky crags, white-sand beaches and coral reefs, are winter breeding grounds for Humpback Whales and marine turtles. For people, they are ideal for snorkelling and diving.

In the far southwest of the long chain of Japan’s islands, about 430 km from Okinawa, are the islands of Iriomote and Ishigaki, part of the Yaeyama Islands, and registered as the Iriomote–Ishigaki National Park. These islands have more extensive mangrove forests than anywhere else in the country, these being particularly evident along Iriomote’s two major waterways, the Urauchi and Nakama rivers. These forests support huge Looking-glass Mangrove trees with their bizarrely snaking buttresses. They are home to the endemic Iriomote Cat, various endemic reptiles including Sakishima Habu1, and endemic amphibians (such as Yaeyama Harpist Frog, Greater Tip-nosed Frog [NT], Utsunomiya’s Tip-nosed Frog [EN], Eiffinger’s Tree Frog, and Owston’s Green Tree Frog), and endemic insects including the endangered Yaeyama Bayadera dragonfly, while the beaches around them are the nesting grounds of both Green Turtle and Loggerhead Turtle.

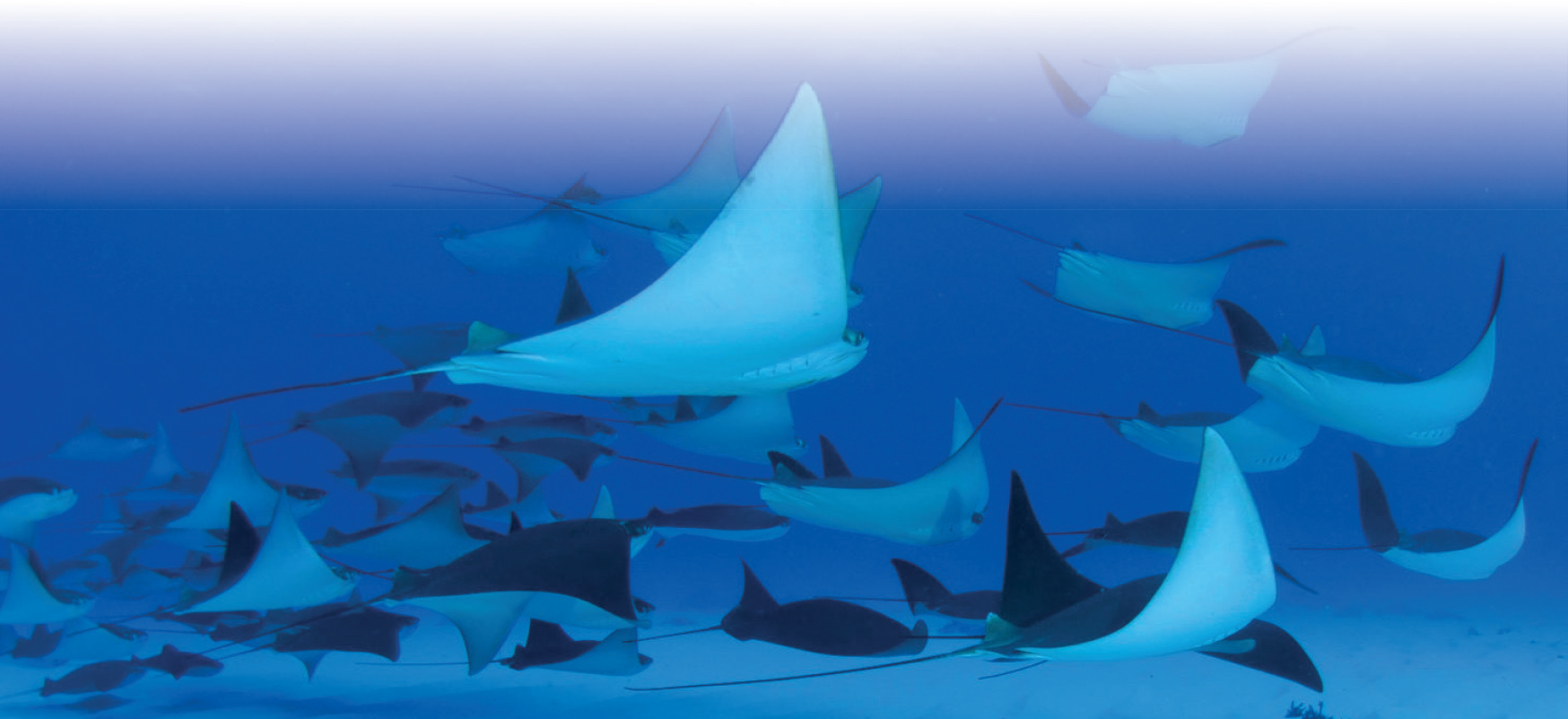

The Sekisei Lagoon, between Ishigaki and Iriomote islands, supports one of the largest coral reefs in Japan, measuring 20 km from east to west and 15 km from north to south, and is home to a wide array of tropical fish. The seas there hold Reef Manta Ray, Whale Shark, Smooth Hammerhead Shark and Great Hammerhead Shark among others, and delicate Black-naped Terns nest on tiny raised coral islets. West of Iriomote-jima is a tiny island that supports breeding Bridled Tern, Brown Noddy and Brown Booby. Iriomote-jima’s forests contain many species of broadleaf evergreens such as various species of chinkapin and bay, and endemic species such as Yaeyama Palm, this last species in an endemic genus known only from the islands of Ishigaki and Iriomote.

Rails, Woodpeckers and Robins – Endemism in the Southern Nansei Shotō

By the late 19th century, Japan’s birds and mammals were better known than those of any other country outside Europe and North America. It was easy to believe during the 20th century that all was already known of what Japan offered. Then an amazing story unfolded: a species new to science was discovered on Okinawa, one of the most heavily populated islands in the land, and not a small cryptic warbler but a large, boldly marked rail – Okinawa Rail.

Top to bottom Hermit Crabs now utilize beach detritus or natural shells for their mobile homes [MAB]; Mudskippers are common in areas with mangrove [MAB]; elegant Black-naped Terns nest on rocky islets offshore [KuM].

Manta Rays can be found in warm waters around the Nansei Shotō and Ogasawara Islands [OVTB].

A number of ornithologists had missed the opportunity and accolade of its discovery. Japan’s great sound recordist, Kabaya Tsuruhiko, had recorded the voice of this species while sound-recording in the area in the mid-1960s, but the then unknown vocalizations were interpreted as novel calls of the rare Pryer’s Woodpecker, which also inhabits those forests. In the early 1970s, the renowned American researcher of woodpeckers, Dr Lester Short, spent time in Yambaru on researching the woodpecker; he noted a rail sighting, but attributed it to a different species known in Japan only from the Yaeyama Islands much farther south and with different plumage features. Either of them, and several others, too, who had made sightings, or taken photographs in the mid-1970s, might have discovered this remarkable species – but did not. That discovery fell to a local resident who found a specimen beside the road and despatched it to the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, then situated in a leafy suburb of Shibuya, Tōkyō. Imagine the surprise of the ornithologists there as they unpacked the parcel and were confronted not just with a rare specimen, but with the very first specimen of a new species. A team set off for the area intent on trapping one, and their success in catching eight more rails led to the species being officially recognized and described in 1981. Back then, nothing was known about the numbers, habitat or behaviour of this new species. All that was known was that the specimen and the few known records were from the northern third of Okinawa, from the forested hills known as Yambaru. It was the first entirely new bird found in the country for more than a century.

The endemic Ryukyu Box Turtle [left KuM] and Black-breasted Leaf Turtle [right SM].

The endangered endemic Yambaru Long-armed Scarab Beetle [left KuM] and endemic Okinawa Ishikawa’s Frog [right SM].

Mangrove forest in the Yaeyama Islands [MC]

Green Turtles nest in the Southern Nansei Shotō [OVTB].

Confined to northern Okinawa Island, Pryer’s Woodpecker is one of the rarest species in Japan [KuM].

Okinawa Rail occurs in much the same range as that of Pryer’s Woodpecker, but is more flexible in its habitat requirements [SM].

It is surprising that this large colourful bird, smartly plumed in slate and silver, with red legs and feet and a large yellow-tipped red bill, could have remained unknown on such a populated island, albeit in the shady forests in the least populated northern third of the island. Today Okinawa Rail is far better known. Its distribution has been mapped, its morphometrics studied, and we know not only that it is flightless but also that it inhabits the highest latitude among all extant flightless rail species. The rail’s flightless nature, seemingly putting it at risk from ground predators in its evolutionary history, had led it to clamber, using its strongly clawed toes, high into trees in which to roost at night, and to descend the next morning by jumping down while wildly fluttering its wings.

Ryukyu Scops Owl ranges throughout the Nansei Shotō and south to the northern Philippines [KuM].

The endemic Pryer’s Scops Owl [KuM]

The endemic Okinawa Robin [RC]

The endemic Kuroiwa’s Ground Gecko [KuM]

The endemic Namie’s Frog [SM]

Then came news of the mongoose. Small Asian Mongoose had been introduced on to the island by people who thought that it would help to reduce the native reptile fauna, particularly a venomous snake. Instead, this predatory alien species ate just about anything, including both adult and young rails. The introduction of the mongoose, combined with the presence of plentiful feral cats, meant that the days of the rail, despite its roosting in trees at night, seemed numbered as mongooses can climb trees; and, in any case, whenever the rails descend to forage or to nest they are at increased risk. As a consequence, rail numbers fell and their range contracted northwards through the 1990s.

Since 2002, great efforts have been made to control the numbers of the rail’s new predator by trapping the mongoose, and trapping appears to have borne fruit and led to an increase in the rail population. The elusive, and largely nocturnal, rail had changed its habits and became more diurnal, but then ran afoul of feral dogs. It is a classic example of how avian species on islands tend towards flightlessness in the absence of mammalian predators, but quickly succumb once such predators are introduced. Today the rails seem as much, if not more, at risk from traffic accidents, as traffic has increased substantially on the roads that now crisscross Yambaru.

Yambaru, the northern part of Okinawa Island, is a biodiversity hotspot. It is home not merely to many species, but also to many endemic species. The area hosts an array of endemic plants and insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and even mammals. At night, endemic frogs, such as a trio of larger species, Okinawa Ishikawa’s Frog, Holst’s Frog [VU] and Namie’s Frog [VU], along with endemic lizards such as Kuroiwa’s Ground Gecko [VU], spice up any search for a roosting rail or a Ryukyu Scops Owl. At dawn, the chorus includes the delightful song of the endemic Okinawa Robin and, sometimes, the sharp tapping of a foraging endemic Pryer’s Woodpecker. During the day, one may find the endemic Okinawan Tree Lizard [VU] and endemic dragonflies such as Yambaru Damselfly, Ryukyu Damselfly and Okinawa Sarasayama Dragonfly. Yambaru is a region that repays visiting at any time of year, during day and night; who knows what new faunal delights will be discovered there!

Japanese Deer

The indigenous Japanese Deer comes in many forms and sizes, small, medium and large, depending on the subspecies. The subspecies in Hokkaidō is the largest, those on Yaku-shima and the Kerama Islands off Okinawa, in the southwest, being the smallest. Individuals may range in colour from pale greyish-tan to warm chestnut-brown and even dark, blackish-brown, depending on the subspecies, gender, age and the time of year.

Resembling small European Red Deer or North American Wapiti, all Japanese Deer, regardless of subspecies, share a black-rimmed rump, a white bottom and a short white tail. The legs are darkest, almost black, with a white spot on the rear of the lower hind legs. The young, females and some stags (males) show rows of pale spots on the flanks, haunches and back. The head is long, with a black muzzle; the medium-long ears are slightly tapered and pointed. They exhibit marked sexual dimorphism. Stags can weigh 50–130 kg, reach 90–190 cm in length and stand 70–130 cm at the shoulder, whereas hinds (females) are smaller, weigh 25–80 kg, measure 90–150 cm in length and stand 60–110 cm tall, although there is a tremendous range in size depending on the subspecies. Hinds have a long slender neck, whereas that of the stags is stockier. Mature stags carry large antlers. The limbs are long, while the feet are small, each foot ending in four toes, the middle two of which are hoofed, and leave strong prints; the hind two toes are shorter, more pointed, but often leave no impression at all.

The natural range of Japanese Deer extends from Vietnam to eastern China, the Korean Peninsula and the maritime provinces of the Russian Far East, while in Japan the species can be found throughout all four main islands, and on various islands off Kyūshū and Okinawa.

Seven subspecies are currently recognized in Japan. Some genetic evidence, however, suggests a major division between the northern forms (C. n. yesoensis of Hokkaidō and C. n. centralis of Honshū) and the southern forms (C. n. nippon of Shikoku, Kyūshū, islands of the Inland Sea and on the Goto Islands, C. n. yakushimae only on Yaku-shima, C. n. megashimae only on Mageshima, C. n. pulchellus only on Tsushima and C. n. keramae of the Kerama Islands.), which may mean that there are in reality two different species.

Body size and antler size vary regionally between subspecies and with level of nutrition. Only males carry antlers, and these increase in their number of points as the animal ages: yearlings have one point, young males of two or three years of age have two or three points, and older, adult males have four or more points on each antler.

The deer live socially, especially in winter, when they are commonly found in single-sex herds. They become more solitary during the summer, although females and their young remain together. Japanese Deer range through various wooded and grassland habitats, from broadleaf evergreen forests in the south to forests of deciduous broadleaf mixed with evergreen in the north. They also favour forest edge and, particularly in Hokkaidō, they are frequently encountered in grasslands, meadows and wetland reed beds. In Hokkaidō, they migrate seasonally so as to avoid areas with deeper snow.

Japanese Deer is a ruminant that grazes and browses on a wide range of plants, which include grasses, such as dwarf bamboos, the leaves, twigs and bark of trees, and fallen seeds and nuts. During winter in snowy areas, the deer are reduced to browsing on tree bark, and their feeding signs are readily distinguished by the fraying of the bark at the upper end of the section where it was first nibbled and then torn from the trunk.

During May and June, the deer moult out of their paler, greyer winter coat into their browner summer coat, and then moult back again during September and October. In late September the annual rut begins, and this continues through October and November. During this season, males become more aggressive, scent-mark, roll in mud, and vocalize more frequently. Their calls consist of a powerful, far-carrying and rather haunting two-note whistle. It is typically heard on autumnal evenings, but can be heard at other times of the day and of the year, too. Their rutting and calling behaviour are part of their competition with other males and an attempt to attract females. The male’s fine set of antlers is used mainly for bluff and bravado, although sometimes also for outright aggressive clashes. The clattering and rattling sound of the antlers of jousting stags is dramatic indeed. The males strut and pose with their fine racks of antlers, hoping to triumph over their competitors in the race to pass on their genes. In their polygynous mating system, larger-bodied and larger-antlered, dominant males establish territories, gather and defend harems, and so obtain most matings. After the seasonal rut, usually by March and April, when the extra burden of their spreading antlers no longer serves a purpose, the stags cast them, like a deciduous tree shedding its leaves. These fallen antlers then become an important source of minerals, and are consumed by rodents, foxes, badgers and deer, or eventually decompose and leach back into the soil. The growing of a new set of antlers each year and then dropping them distinguishes deer from other animals with horns, such as sheep, goats, cattle and antelopes. Those animals, unlike the deer, have simple, non-branching structures of bone, covered with keratin, on their forehead and they keep them throughout their lives.

In spring each year, usually during late May after gestating for around 230 days, females give birth to a single fawn (twins and triplets occur, but very rarely). Males may live for up to 15 years and females up to 20 years, but many do not survive even long enough to begin breeding from two years of age.

When disturbed or alarmed, deer stand alert with ears erect, watching carefully, and they may stamp a fore foot. If they continue to sense danger, they raise the tail and fluff out the white fur of the bottom to a considerable size, making themselves very conspicuous from behind. On fleeing, they give a short, sharp alarm whistle while dashing away with tail raised and rump fluffed out. The young, in herds or with their mothers, also give strange wheezing calls. The combination of raised tail and fluffed white bottom makes for a strong visual signal, especially in shady forest or poor light, allowing disturbed herd members to follow one another easily. The sharply whistled alarm call always gives the watcher a jolt of surprise, even those who have heard it innumerable times.

Various subspecies of Japanese Deer occur in the archipelago, the largest of these in Hokkaidō, the smallest on the Kerama Islands, off Okinawa, and on Yaku-shima. The deer (male left; female right) on Yaku-shima share their range with the southernmost Japanese Macaques [BOTH IiM].

Left Japanese Deer will dig down through snow to reach food in regions where snow covers the ground; right when food is limited, Japanese Deer resort to stripping tree bark [BOTH MAB].

Japanese Deer commonly segregate into single sex herds (here a group of females and young) [WaM].

Wild Boar

Wild Boar is not a party-pooper, nor a domestic pig gone feral. This truly wild species has the widest distribution of any pig. In addition to ranging across Europe and North Africa, and across Eurasia to India and Indonesia, it is found widely throughout central and southern Japan from central Honshū to the Ryūkyū Islands.

Wild Boar [YaM]

A medium-sized stocky, even rotund pig, Wild Boar has an almost neckless appearance, with a broad head, short rounded ears, and a long snout, the tip of which is partly prehensile. The males have four tusks and are around 20–30 percent heavier than females, but size varies from region to region, those in the southwest islands being the smallest and lightest. The larger subspecies (S. s. leucomystax) occurs widely in central and western Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū, but not at all in northern Honshū or Hokkaidō. The smaller subspecies (S. s. riukiuanus) is restricted to the Nansei Shotō, from Amami Ōshima to Iriomote Island. Measuring 110–160 cm long and standing 60–80 cm tall at the shoulder (males), these animals range between 50 kg and 150 kg in weight, depending on subspecies, region, gender and age.

The coat of Japan’s Wild Boar contains coarse bristles and varies in colour from pale greyish-brown to dark blackish-brown, the legs being typically darkest. The short, straight tail is covered with short hairs. Piglets are a paler, warmer orange-brown with stripes. Their limbs are powerful, each ending in four toes, leaving strong prints very similar to those of the larger Japanese Deer. In snow, Wild Boar plough like manic bulldozers, leaving deep furrowed impressions.

Terrestrial, nocturnal and crepuscular, Wild Boar live solitarily, in small all-male groups, or as extended family groups consisting mainly of females and their young. This species lives mainly in natural evergreen and deciduous broadleaf forests, but can be found also in secondary forests, at forest and woodland margins, and in agricultural land (rice and other crop fields) where these are adjacent to woodland.

The omnivorous Wild Boar eats plant and animal foods taken from the surface or from just below the surface of the ground. Its diet includes roots, tubers, leaves, stems, fruits, nuts, invertebrates (especially earthworms and snails), amphibians, reptiles, and ground-nesting birds. In autumn, boar are attracted particularly to concentrations of food, such as fallen acorns and fallen fruit. Extensive areas of disturbed surface soil are typical signs indicating where Wild Boar have been rooting for food.

Males mature at two years of age, but females are ready to breed at one year and typically give birth once a year in spring, although rarely they may produce a second litter in the autumn. Following a gestation period of 120 days, females may give birth to a litter of up to ten young, although in the northern subspecies litters average fewer than five young and in the southern subspecies fewer than four. Most young Wild Boar do not reach their first birthday. Those which do, however, may go on to reach ten years of age.

Japan’s smallest Wild Boar subspecies lives in the Nansei Shotō [TsM].

Ploughed ground is evidence of the presence of Wild Boar [MAB].

Southern Mixing Grounds

The many islands and channels of the Nansei Shoto and their geological histories have created a complex mixing zone. Many species at home in mainland Japan or Northeast Asia reach their southern limits here and mingle with those more frequently associated with regions farther south, which have their northern limits in this zone.

Among the herons, egrets and bitterns, for example, Malayan Night Heron [NT] and Purple Heron reach the northern limits of their ranges in the Yaeyama Islands, while Cinnamon Bittern reaches north through the Nansei Shotō Islands as far as its northern limit of Amami Ōshima. More northerly breeding species, such as Grey Heron, Black-crowned Night Heron and Yellow Bittern, move south to these islands, but only for the winter.

Each year, Chinese Pond Heron, something of a rarity in Japan, wanders northwards and individuals reach these islands. Conversely, Black-faced Spoonbill, a globally rare species breeding on the Korean Peninsula, winters here in small numbers. The islands are truly a biogeographical crossroads.

Left to right Cinnamon Bittern reaches its northern limit in Japan in the Nansei Shotō; Chinese Pond Heron wanders regularly northwards to the southern Nansei Shotō; Eastern Yellow Wagtails are scarce winter visitors to the southern Nansei Shotō, but breed in northern Hokkaidō [ALL TsM].

Left to right Purple Heron reaches its northern limit in Japan in the Nansei Shotō [KT]; Malayan Night Heron occurs in the Yaeyama Islands each winter [MC]; small numbers of the rare Black-faced Spoonbill winter in the southern Nansei Shotō [TsM].

In the northern half of their Japanese range, the deer must contend with snow in winter. Deep powdery snow is to a Japanese Deer what a stage covered with fluffy feather pillows would be to a top-ranking ballerina. Both lead to loss of grace and floundering for slim-footed deer and ballerina alike. The narrow-hoofed deer sink and flounder, so they prefer areas with shallower snow. By way of contrast, on the southern island of Yaku-shima they must contend with heavy rain.

On Yaku-shima, where the deer share their range and habitat with Japanese Macaques, and live with them in a loosely symbiotic way, the deer are used to the miraculous appearance of fresh food from above, thanks to the messy eating habits of the monkeys. ‘Miraculous provisioning’, however, is not restricted to the deer living on Yaku-shima. With the passion that human visitors in Japan have for feeding living creatures at tourist spots, those deer that overcome their shyness sufficiently to approach tourists are guaranteed handouts. This happens frequently at Itsukushima shrine on Miyajima, and at Nara, although unfortunately many of the deer end up consuming litter and plastic, too.

Top to bottom The non-venomous Japanese Ratsnake is widespread from Hokkaidō to Kyūshū but absent from the Nansei Shotō [MAB]; Ryukyu Odd-toothed Snake [SM]; Japanese Striped Snake [JoW]; Tiger Keelback [MAB].

Japan’s Reptile Fauna

The gradient in climate from northern temperate in Hokkaidō to subtropical in Okinawa is reflected by patterns of biological distribution. Yet, while the gradient in richness in the Northern Hemisphere is typically towards the equator, as is found among the reptiles and amphibians of Japan, the pattern is strangely reversed for the mammals: the farther north one goes in Japan, the greater the number of mammal species, Japan’s northern prefecture Hokkaidō supporting the most. Perhaps other factors are involved here, such as the area of the prefecture and its diversity of habitats, but clearly much remains to be understood even in a well-studied country such as Japan. As mentioned, when looking at reptiles we find that the opposite pattern is the case: there are fewer species in the colder northern regions and many more in the subtropical south. Despite those southwest islands having a much smaller land area, they have a much greater diversity of reptiles.

Japan’s reptile fauna includes various marine turtles, freshwater turtles, several geckos and ground geckos, lizards, numerous skinks, and a wide range of snakes including pit vipers and sea snakes. Forty-three of Japan’s reptile species are endemic, and most of these occur in the south.

Top left Although venomous, Japanese Mamushi is rarely aggressive [HT]; top right the endemic Japanese Coral Snake [TsM]; bottom left the endemic Ryukyu Green Snake [SM]; bottom right Okinawa Tree Lizard [KuM].

The most frequently encountered of Japan’s native reptiles is the non-venomous Japanese Ratsnake. While its English name seems rather unfortunate, its Japanese name of Aodaisho (literally ‘green commander’) is far more imposing. It ranges from Hokkaidō to Kyūshū but is absent from the southwest islands, and is as likely to be found in urban parks as in rural areas. This is the largest of Japan’s main island snakes, reaching lengths of 1–2 m and with a diameter of about 5 cm. Although frequently a mottled dark green, this species varies, some individuals being pale yellow-green. As its name suggests, it is primarily a rodent-hunter.

Venomous snakes, too, occur here. Japanese Mamushi2, which grows to less than a metre in length, is a widespread species occurring from Hokkaidō to Kyūshū and Yaku-shima in a range of habitats, from marshes to rocky hillsides. Although venomous, it is rarely aggressive. Japanese Mamushi, Japanese Coral Snake and Okinawa Habu are the three most venomous snakes in Japan. The last-mentioned is endemic to the southwest islands, and grows to 1·2–1·5 m on average, some individuals reaching as much as 2·4 m, making it Japan’s largest snake. This terrestrial and almost entirely nocturnal species is most likely to be found in forest and farmland edge habitats, and has a reputation for being irritable.

From the alarming to the charming, few reptiles are as attractive as another of the Nansei Shotō’s endemic species, this one known as Kuroiwa’s Ground Gecko. This endangered species is in fact very likely to consist of two separate species, those on the Amami island group being genetically very distinct from those on the islands of Okinawa to the south. Their genetic divergence dates back to the middle Miocene, about 14 Mya, which was even before the formation of the straits that have constantly separated these island groups since the early Pleistocene, about 2.5 Mya.

Forests Where the Tides Flow

Saltwater brings death to most trees, yet there are those – the mangroves – that are specially adapted to it. Where warm-water rivers merge with the sea, there is an ebb and flow, and not just of the tide. Rivers carry silt and detritus downstream towards their estuaries and the sea beyond, depositing these materials steadily seaward in an endless invasion of the marine realm by the terrestrial world, in a process known as accretion. Unwittingly fighting back against the process of accretion, the next winter storm or summer typhoon may undo the work of months in a matter of hours, eroding away the accumulated silt and washing it out into the deep ocean, but only for the process of coastal accretion to recommence, as if with infinite patience.

Along the flanks of the river’s estuary an army awaits. This is a sluggish army moving only slowly seawards. No other force moves in this way – not in a rapidly advancing phalanx intent on attack, but moving inexorably, generation by generation, to take over newly created territory. This is an army that marches not on its stomach, but on its stilts along the margins, holding deep into the mud, grasping at it, and stabilizing it until the land beats back the sea. This army consists of mangrove trees. At high tide, the trees of the mangrove militia stand in ranks with their roots and trunks amid swirling deep saltwater; their dark leathery green leaves shine glossily in the harsh subtropical noonday sun. At low tide these botanical amphibians stand surrounded by sand-mixed mud; their stems twist and rise drunkenly, supported by a network of snaking stilt and prop roots.

The surface of the ultra-fine mud sediment becomes slick as the tide drains away; skating here is easier than walking. Dig beneath the seemingly benign grey surface of the drying mud and what rises from it can only be called a stench. Within a few centimetres of the surface, the sucking mud is dense, black, and emits the foul odour of decay. This perpetually waterlogged soil holds little free oxygen, and is laden with anaerobic bacteria that release among other things methane, nitrogen and sulphides that contribute to that gagging, rotting stench. That anything grows here is incredible. That an army of forest trees can march steadily through this muck is little short of miraculous. These are the conditions of a harsh environment in which moisture, salt concentrations and temperatures swing back and forth between extremes that would kill most species within hours.

While most plants are excluded by just these conditions, mangroves somehow thrive. Here, in this unstable, tide-washed salt-laden ‘land’, they have the competitive edge over other plants. They cope with the alternate wetting and drying of their roots caused by tidal inundation, and as halophytes their resistance to salt concentrations (which may rise as high as 90 parts per thousand) makes them tougher survivors than other plants. They may not grow massive trunks, or reach high into the sky, as do many other tropical or subtropical trees, but instead their many stilted roots lend them physical stability in a fine, shifting soil that would soon undermine other species – that is if it did not kill them through its lack of oxygen!

The cloying silt that excludes most species is something that the mangroves can turn to their advantage. Spongy tissues in their roots aid them with gaseous exchange, but more unusual and critical to them is their array of exposed breathing tubes. All plants require oxygen for respiration, including in the tissues of their underground roots. Like a swimmer relying on a snorkel, stretching up from the inhospitable water into the atmosphere, mangroves have breathing tubes that stretch up, like grasping fingers, from the inhospitable glutinous mud, giving them access to life-giving air. These aerial roots, known as pneumatophores, and the stilt-like prop roots, are modified in such a way as to be capable of absorbing gases directly from the atmosphere and transporting them to the roots buried below mud. They are so vital that a single mangrove tree may have as many as ten thousand of them bristling up above the mud for 10–30 cm.

Only 54 species of tree worldwide are considered true mangrove species, each adapted slightly differently to this saline environment with anaerobic soil, but they come from very varied taxonomic backgrounds, being defined more by their ecological adaptations than by their evolutionary relationships. This is an example of convergent evolution, whereby unrelated organisms evolve similar characteristics in order to thrive in a particular set of environmental conditions and do not represent a single natural taxonomic group. Some avoid taking in salt in saltwater by filtering most of it out at the surface of their roots; that, combined with a degree of salt tolerance not found in most other plants, allows these salt-excluding species to survive with ten times more salt in their sap than most plants can tolerate. Other mangrove species take in saltwater, but excrete concentrated salt from glands on their leaves in a process that still leaves them having to tolerate salt concentrations in their sap ten times that of the salt-excluders.

Mangrove plant species are adapted to daily tidal inundation by saltwater and occur in Japan’s warm regions. Top left Black Mangrove [BOTH TsM]; top right Kandelia Mangrove [BOTH TsM]; bottom left spear-shaped mangrove propagules self-plant in soft mud, but may also be transported by the tide [TsM]; bottom right branched mangrove roots support the trees and serve to stabilize coastal soils and block tidal surges [KuM].

Among the mangroves Barred Mudskipper [inset KuM] is capable of surviving out of water for part of the tidal cycle [TsM].

These extraordinary trees form forests where they can, in saline coastal sediments and in estuaries in tropical and subtropical regions around the world, but with an uneven distribution such that Asia alone has more than 40 percent of the world’s mangroves. Despite their toughness in the harsh conditions of the intertidal zone, mangroves are sensitive to cool temperatures that prevent them from colonizing the temperate zone. At their extremes they extend north as far as southern Japan and as far south as New Zealand’s North Island and Australia’s Victoria coast. Although mangroves have for long been cleared to make way for coastal development and for shrimp ponds, or been burned as fuel, the immeasurable value of this biome, with its many mangrove trees, as a protective ‘bioshield’ for the coast and what lies immediately inland of it was brought into sharp relief by the devastating force of the 2004 Southeast Asian tsunami in areas unprotected by mangroves.

Where mangroves grow, they slow the flow of water and form a buffer between land and sea; they drain power from onshore waves, and accumulate ever more silt around their roots. As they grow and spread towards the ocean, they leave behind drier, richer areas that other plant species can colonize in succession.

Their extensive above-ground roots and pneumatophores and their complex mesh of fine rootlets within the soil all serve to trap and hold sediments as they spread tidewards. Their root system helps them to stabilize and build up soils and to block tidal surges, resist erosion during high-energy tropical storms and typhoon floods, and even help to abate tsunami. An additional benefit is that their trapping of sediments allows coral reefs to develop in clear water offshore. Where mangrove forests are retained, onshore damage from tsunami is greatly reduced. Even when damaged by storms, mangroves are remarkably quick to recover as they produce abundant propagules which, having already germinated before implantation, grow rapidly. The growing trees mature quickly, further speeding the process of regrowth and recolonization.

Even in the typically richly biodiverse tropics, where terrestrial forests may contain thousands of tree species, it is not unusual for mangrove-forest diversity to be as low as three or four species. While there may be few trees in the swamps that we call mangroves, this habitat supports a tremendous array of other species, from barnacles, bats and birds to sponges, crabs and mudskippers. Mangroves are true keystone species.

Mangrove trees have an array of fascinating adaptations to their environment, even utilizing the flow of the tide to help them to disperse their seeds. Most mangroves are hermaphrodites, with their flowers pollinated almost exclusively by small insects, birds and bats. Whereas most plants produce seeds that must disperse before germination in soil, many mangrove tree species produce seeds that germinate while still attached to the tree, in a process known as vivipary. What look like long green cigars hanging from the branches are in fact the already germinating fruits. These ready-to-go propagules are actually seedlings already capable of photosynthesizing to produce their own food by using the sun’s energy. Once mature, they fall from the mother tree, where the tide can carry them long distances. Able to remain dormant for over a year, to survive in saltwater and to resist desiccation, some propagules are eventually washed on to a suitable substrate, where they lodge in the mud and take root.

Japan’s mangrove forests are at the northern limit of their Indo-Pacific range and include a number of species, particularly: Black Mangrove, Narrow-leaved Kandelia, Spider Mangrove, Grey Mangrove, two species both known coincidentally as Looking-glass Mangrove, Mangrove Apple, and Mangrove Palm. They form an exotic landscape of various species growing modestly to 5–8 m in height and mostly confined to the country’s subtropical southwest islands from Amami Ōshima to Iriomote-jima, although some grow as far northeast as Shizuoka Prefecture, Honshū. Along with coral reefs, they attract many tourists to the warmer southern parts of the country. Japan even has a protected mangrove forest: Nagura Anparu, on Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture. A wildlife-protection area since 2003, it was designated a Ramsar Site in November 2005. Nagura Anparu may spread only some 157 hectares at the mouth of the Nagura River, but it is an important home to about 60 species of crustacean and many species of bird, and is popular for recreational sightseeing and birdwatching.

Various crabs forage across the tidal mudflats in mangrove forests: Milky Fiddler Crabs (top left) seem dwarfed by their own claws; Asian Soldier Crabs (top right); Orange Fiddler Crabs (middle left); Orange Mud Crab (middle right); Tetragonal Fiddler Crabs (bottom left); and Dussumier’s Fiddler Crabs (bottom right) [ALL TsM].

1 A pit viper endemic to most of the islands of the Yaeyama Archipelago.