An Overview of Japan’s Birds

Almost 750 species of birds have been recorded in Japan, these comprising regularly occurring native species, introduced species, and a large number of rare migrants or accidentals.

The birds of Japan (along with those of Sakhalin, the Kuril lslands, Korea and Taiwan) have much in common with the Asian continental avifauna. The Japanese archipelago, once the mountainous rim of the Asian continent itself, was subsequently separated by the opening of the Sea of Japan basin. Certain Siberian avian species, adapted to tundra, taiga and subarctic conifer forest, reach Japan as these essentially northern birds penetrate south on high mountains in central Honshū. There are also a few Philippine and Malayan elements. While Japan inevitably shares much of its avifauna with the adjacent islands, peninsulas and the nearby continent, a proportion of its species are endemic – found nowhere else in the world.

Japan has been isolated from the Asian continent for long enough in some cases for unique forms to have evolved in that country, and the further isolation of smaller archipelagos within Japan has been sufficient for island endemics to have evolved there, too. Thus, there are endemic bird species occurring on the four main islands of Japan as a group (Hokkaidō, Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū), and others restricted just to the lzu Islands or the Nansei Shotō, or even to just parts of those island chains.

A scientific understanding of the differences between the birds and other animals of Japan and the Asian continent and among the various parts of Japan began during the latter half of the 19th century. An understanding of the early separation of Hokkaidō from Honshū by the Tsugaru Strait allowed the recognition that Hokkaidō was strongly influenced by the Siberian region farther north, whereas Honshū was most conspicuously influenced from the south. The Tsugaru Strait forms a crucial divide through which passes Blakiston’s Line (see p. 11). The second most important zoogeographical division is that between the Palaearctic Region and the Oriental Region, which falls between the islands of the southern Nansei Shotō. Although generally impoverished in biological terms relative to the main islands, the Nansei Shotō show many more southern characteristics than do other areas of Japan, yet are clearly influenced also from the north. The whole chain represents a transition zone between the two regions.

Steller’s Eagle is a winter visitor to northern Japan [PP].

Japan’s avifauna is, as described above, a complex mixture of north and south. This mixture, combining elements of the Palaearctic (Sino-Manchurian and Siberian) and Oriental/lndo-Malayan, even Himalayan, Regions, with the addition of a number of endemic species, means that Japan’s avifauna is a complex and fascinating Asian cross-section. This mixture is emphasized further by the seasons. In winter, Japan hosts many northern species, particularly waterfowl, raptors and many woodland passerines. In summer, Japan sees birds arriving from Southeast Asia, from the Philippines and from as far as Australasia. Summer visitors and year-round residents make up a breeding avifauna of more than 250 species. The birds of Japan can be separated into six types: residents present throughout the year, summer visitors, winter visitors, passage migrants1, wanderers2, and accidentals3.

Despite the great length of the Japanese archipelago, and its wide range of habitats and climates, a number of species are resident throughout a large part or even all of this range. These include Eastern Spot-billed Duck, Ural Owl, Varied Tit, Japanese White-eye, Oriental Greenfinch and Japanese Crow. Others are resident but occur only in certain parts of Japan. Some of these are endemic; two examples are Copper Pheasant and Japanese Woodpecker, both of which are absent from Hokkaidō and the Nansei Shotō.

Many birds occur in Japan only as summer visitors, and spend their winters in southeastern China, Malaysia or elsewhere in Southeast Asia, including the Philippines and Indonesia. Summer visitors include Eastern Cattle Egret and Intermediate Egret [NT]4, Grey-faced Buzzard, Northern Boobook, Siberian Blue Robin, Japanese Thrush, Blue-and-white Flycatcher, Yellow Bunting and Chestnut-cheeked Starling.

A wide range of species visits Japan only in winter. These migrate here from places that include the Kuril Islands, Kamchatka, southeastern and northeastern Siberia, Ussuriland, Sakhalin, northeastern China and even Mongolia. Winter visitors include Hooded Crane and White-naped Crane, the swans, geese and many ducks, Common Guillemot5, Common Black-headed Gull, and passerines such as Eastern Rook, Daurian Jackdaw, Dusky Thrush and Pale Thrush, Brambling, and Elegant Bunting and Rustic Bunting.

Because Japan lies on the migratory route between more northerly breeding grounds and more southerly wintering areas, naturalists can see large numbers of a wide range of migrants passing through. In particular, large numbers of many species of shorebird and seabird visit each year, as do species such as Garganey and Grey-streaked Flycatcher.

Many resident bird species undertake short-distance seasonal movements within the country, either altitudinally, between regions, or between islands. There is a major autumnal southerly exodus of small passerines from Hokkaidō to Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū. Such movements are complemented by influxes of the same species from outside Japan, so that a species may be both a visitor and a seasonal wanderer. Typical wanderers include Japanese Accentor, Japanese White-eye, Meadow Bunting and Masked Bunting, Bull-headed Shrike and Oriental Greenfinch.

A large number of species from well outside their normal ranges have also been recorded as accidentals, with new species added to the Japanese list in most years. Individuals may be diverted from their normal course by storms or typhoons, or overshoot the ends of their normal routes. Species that occur irregularly or may have been observed only once or twice include WiIson’s Phalarope, Franklin’s Gull and Common Yellowthroat from North America, Eastern Grass Owl probably from Southeast Asia, Collared Kingfisher and White-breasted Wood Swallow from the Philippines or possibly Micronesia, Yellow-browed Bunting from continental East Asia and Fieldfare, Mistle Thrush and Wood Warbler from Eurasia.

The isolated Japanese islands are home to a number of resident endemic birds. Some are widespread throughout Japan, while others are restricted to a single island. Another group of species can be called endemic breeders, as they breed in Japan and nowhere else, but migrate out of the country for the winter. Finally, a third group (near-endemics) reflects the fact that far-east Asia is itself a centre for endemism; a number of species are found primarily in Japan, but they occur also on adjacent islands or the continental coast, such as Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands or the Sea of Okhotsk coast.

The endemic Copper Pheasant, here a female, consists of several regional subspecies [KT].

Birds endemic to Japan and adjacent territories include Japanese Murrelet, Okinawa Rail, Amami Woodcock, Green Pheasant and Copper Pheasant, Japanese Woodpecker, Pryer’s Woodpecker and Owston’s Woodpecker, Japanese Wagtail, Ryukyu Minivet, Japanese Accentor, Izu Robin, Ryukyu Robin and Okinawa Robin, Amami Thrush and lzu Thrush, Owston’s Tit and Orii’s Tit, Bonin Honeyeater and Lidth’s Jay.

Japanese Night Heron is an endemic breeder in Japan but winters elsewhere [KuM].

Endemic breeders include Short-tailed Albatross, Matsudaira’s Storm Petrel, Japanese Night Heron, Latham’s Snipe, Ijima’s Leaf Warbler, Yellow Bunting and Chestnut-cheeked Starling. The near-endemic breeders include Temminck’s Cormorant, Streaked Shearwater, Swinhoe’s Storm Petrel, Black-tailed Gull, Ryukyu Scops Owl, Japanese Wood Pigeon, Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker, Brown-eared Bulbul, Japanese Robin, Brown-headed Thrush, Narcissus Flycatcher, Japanese Paradise Flycatcher, Varied Tit and Grey Bunting.

Okinawa Rail is a single-island endemic breeder in Japan [MAB].

Regional Distribution of Japanese Birds

The topography of Japan, with numerous islands and major mountain ranges, presents many barriers to species’ dispersal and interaction. The regional distribution of birds has for long been a subject of great interest.

The Japanese avifauna readily lends itself to regional subdivision into four major geographical areas: (1) Hokkaidō; (2) Central Japan (Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū); (3) the Nansei Shotō; and (4) the Izu, Ogasawara and Iwō Islands. As a result of the great distances separating some of these, a species may well be of different status in different regions; thus, both Common Redshank [VU] and Eastern Yellow Wagtail are summer visitors to Hokkaidō, uncommon migrants in Central Japan, and winter visitors to the Nansei Shotō, while Bewick’s Swan is a migrant in Hokkaidō and a winter visitor in Central Japan. As a result, general statements about the avifauna of Japan must always be made in the context of the particular region. Having said that, some species are found virtually throughout all or most of Japan, including Oriental Turtle Dove, Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker, Japanese Bush Warbler, Japanese Tit, Japanese White-eye, Japanese Crow, Eurasian Tree Sparrow and Oriental Greenfinch.

Hokkaidō

The avifauna of Hokkaidō is, with few exceptions, exclusively northern Palaearctic (the exceptions are the penetration northwards of Northern Boobook, Japanese White-eye and Brown-eared Bulbul), and bears a strong similarity to that of regions to the north and northwest, such as Sakhalin and Ussuriland.

Hokkaidō is separated only by the narrow Sōya Strait from Sakhalin, just to the north, and shares with it many species. While Sakhalin is very similar to Siberia in its avifauna, however, Hokkaidō lacks a number of true Siberian species. Even so, Hokkaidō forms the southern limit for a number of northern cold-adapted species which breed or have bred no farther south in Japan than Hokkaidō. Such species include Red-necked Grebe, Red-faced Cormorant, White-tailed Eagle, Falcated Duck, Gadwall, Northern Shoveler, Tufted Duck, Smew, Common Merganser, Hazel Grouse, Red-crowned Crane, Common Redshank, Common Guillemot and Spectacled Guillemot, Tufted Puffin, Blakiston’s Fish Owl, Grey-headed Woodpecker, Lesser Spotted Woodpecker and Eurasian Three-toed Woodpecker, Sand Martin, Sakhalin Grasshopper Warbler, Marsh Tit and Pine Grosbeak.

Other birds breed almost exclusively in Hokkaidō, but have bred in or have colonized northern Honshū. These include Leach’s Storm Petrel, Northern Hobby, Slaty-backed Gull, Eurasian Wryneck, Siberian Rubythroat and Long-tailed Rosefinch.

Hokkaidō is also the northern limit for a range of southern, warm-adapted species such as Japanese Grosbeak, Japanese Wagtail, Japanese Accentor, Bull-headed Shrike and Blue-and-white Flycatcher, all of which occur as far north as Hokkaidō, but do not breed in Sakhalin. The southern islands of the Kuril chain, including Kunashiri, Etorofu (Iturup) and Urup, form an extension of the Hokkaidō avifauna. Hokkaidō is also on the migration route of, for example, Greater White-fronted Goose, Taiga Bean Goose [NT] and Bewick’s Swan, all of which migrate through Hokkaidō to winter farther south in Central Japan.

Central Japan – Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū

By far the majority of species on the Japanese list have been recorded from the central region of Japan consisting of Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū, which although predominantly Palaearctic is greatly influenced by the proximity of the Oriental Region. In fact, while in winter it is easy to accept the predominant Palaearctic influence, it is far more difficult to do so in summer, when the climate, the vegetation and the birds suggest an almost tropical setting. The central region receives the greatest number of migrants and accidentals, but also attracts certain species that breed neither farther north nor farther south in Japan, and is home to several endemics. This group of species breeding only in Central Japan includes Swinhoe’s Storm Petrel and Band-rumped Storm Petrel, Striated Heron, Eastern Cattle Egret and Little Egret, Common Kestrel, Rock Ptarmigan, Copper Pheasant and Green Pheasant, Dollarbird, Japanese Green Woodpecker, Fairy Pitta, Grey-headed Lapwing, Greater Painted Snipe, Tiger Shrike [VU], Alpine Accentor, Marsh Grassbird, Japanese Reed Bunting and Yellow Bunting, Azure-winged Magpie and also, thanks to a successful captive-breeding and reintroduction programme, Crested Ibis and Oriental Stork. Two further endemics, Japanese Wagtail and Japanese Accentor, breed in Central Japan and in Hokkaidō, but not in the Nansei Shotō. Fairy Pitta and Dollarbird, both summer visitors, and Greater Painted Snipe, a local resident, are notable since they are of tropical origin yet occur north to central and even northern Honshū on occasion.

A number of species have colonized Japan from the south with only limited success, and are relatively more abundant in the warm temperate region of the south; examples include Japanese Night Heron, Striated Heron, Pacific Reef Egret, Grey-faced Buzzard, House Swift and Japanese Paradise Flycatcher. Other colonists have spread rapidly, extending their range even to the cooler north. One, Red-rumped Swallow, has even bred in Hokkaidō on occasion.

The high-elevation habitats provided by the mountains of central Honshū enable some northern species, such as Spotted Nutcracker, to breed farther south in Japan than they might otherwise do. Conversely, the warm current along the Pacific coast allows other species of southern origin but which have not fully adapted to cooler regions, such as Pacific Reef Egret, Intermediate Egret and Greater Painted Snipe, to breed farther north than might otherwise be expected. There is also a relict species, Rock Ptarmigan, a small isolated population of which remains at high elevations in the Japan Alps – the result of climatic changes.

The Nansei Shotō

The Nansei Shotō, the island chain in Japan where the northern limit of the Oriental Region and the southern limit of the Palaearctic Region intergrade, has elements from both regions, making the avifauna and other fauna of the Nansei Shotō of great interest and importance.

A number of endemic birds have evolved in the Nansei Shotō. Some of these range throughout the island chain, such as Ryukyu Robin (which occurs from the Danjo Gunto islands west of Kyūshū in the north to the Yaeyama Islands in the south) and Ryukyu Minivet (which not only occurs from Yaku-shima to the Yaeyama Islands, but has recently extended its range beyond the islands into Kyūshū and even Honshū). Amami Woodcock breeds on Amami Ōshima, and some winter south to Okinawa. Lidth’s Jay, Owston’s Woodpecker and Amami Thrush are restricted to just Amami Ōshima. Pryer’s Woodpecker, Okinawa Rail and Okinawa Robin are restricted to northern Okinawa; while Ryukyu Scops Owl is virtually an endemic, occurring commonly from Amami Ōshima to Yonaguni-jima, then only on Lanyu Island off southeast Taiwan, and on the tiny Batanes and Babuyan Islands of the north Philippines.

In addition, many southern species breed in the Nansei Shotō but no farther north. These include Cinnamon Bittern, Malayan Night Heron, Purple Heron, Barred Buttonquail, Slaty-legged Crake [VU], White-breasted Waterhen, Ryukyu Green Pigeon, Pacific Swallow and Light-vented Bulbul. The islands thus form the northern limit for these species, yet at the same time they are the southern limit for other species, such as Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker.

A number of seabirds, such as Greater Crested Tern, Black-naped Tern, Roseate Tern, Sooty Tern and Brown Noddy, have important colonies among the Nansei Shotō. Moreover, in 1988, Short-tailed Albatross6 was confirmed as breeding on the isolated Senkaku lslands. Compared with Central Japan and Hokkaidō, Nansei Shotō hosts relatively few winter and summer visitors, but instead these islands receive many migrants and accidentals and are the wintering grounds for small numbers of a wide range of shorebirds.

The Izu, Ogasawara and Iwō Islands

These isolated oceanic islands, particularly the Ogasawara Islands and Iwō Islands, have few resident species and few seasonal visitors, but they have attracted a long list of accidentals, and have a number of interesting breeding species such as: Short-tailed Albatross and Black-footed Albatross, Bonin Petrel, Matsudaira’s Storm Petrel, Bulwer’s Petrel, Greater Crested Tern and Black-naped Tern, Brown Noddy, lzu Thrush, ljima’s Leaf Warbler, Izu Robin, Owston’s Tit and Bonin Honeyeater.

Migration

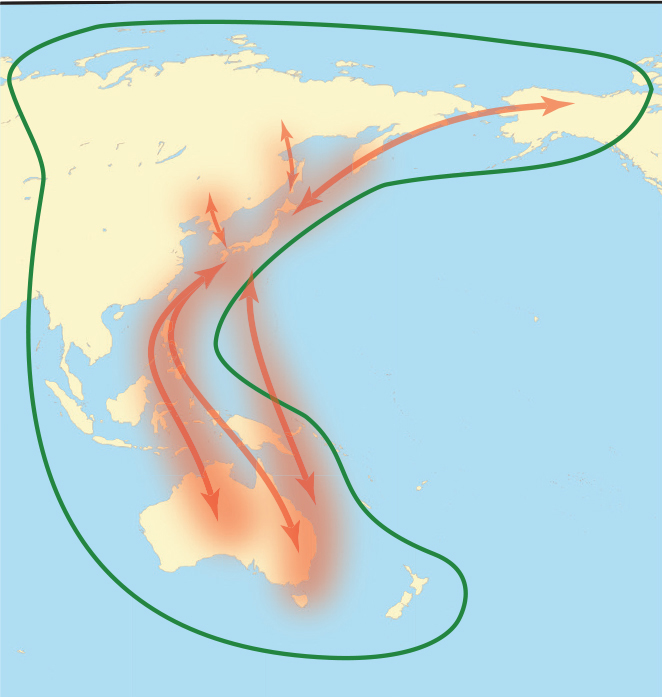

The East Asian–Australasian Flyway is one of the world’s most important bird-migration routes linking points from northeastern Russia all the way to southeast Australia through the birds that travel between them. Conserving those birds means protecting not only their breeding grounds, often in the far north, but also the wintering grounds in the south and their vitally important refuelling stop-over locations along the way.

The shapes of present-day migration routes carry imprints of past coastlines prevalent during times of glaciation. At the height of ice ages, trans-ocean migration routes were shorter, whereas now when we are in an interglacial the distances that birds must cover are very much greater. On spring migrations some birds of the East Asian–Australasian Flyway in effect follow a fossilized route, while on their return in autumn they follow newly derived, more direct routes.

The East Asian–Australasian Flyway The green boundary indicates the extent of the flyway and the red areas and arrows show the main routes and directions taken.

Bird-migration routes that include Japan have likely evolved in relation to long-term changes in the Asian continental coastline, and the elevation of mountain ranges now forming the spine of Japan. Initially, a major route is presumed to have extended along the then Asian continental coast, eventually becoming the Kuril Islands–Japanese Islands–Nansei Shotō–Taiwan route. Routes along the coasts of the newly formed Sea of Okhotsk depression led to an extra route down what is now Sakhalin, while farther south migration routes along the coasts of the Sea of Japan depression led to current routes from Asia to Japan via the Noto Peninsula and down the eastern side of peninsular Korea into southwestern Japan and Kyūshū. The East China Sea depression led to a further route extending along what is now the continental coast of the East China Sea, some birds crossing directly from Kyūshū to Taiwan, bypassing the Nansei Shotō.

Because of Japan’s geographical position, mountainous terrain and climatic zones, the classification of birds into various categories is not an easy task. Nevertheless, some are clearly residents, winter visitors, summer visitors, passage migrants or accidentals, while some make vertical migrations, and others are resident within the country yet make local migrations. In some cases, such as Oriental Greenfinch, certain subspecies breed in Japan but move south and are replaced in winter by subspecies from farther north.

In short, ‘Japanese birds’ come from as far north as the arctic coasts and tundra of Siberia and even Alaska and from as far east as continental USA, and they range as far west as Myanmar, southwest to the Malay Peninsula, south to the Philippines, to New Guinea and even to Australia as far south as Tasmania and, in the case of South Polar Skua, Antarctica.

The study of migration is advanced mainly by the bird-ringing scheme organized in Japan through the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, while direct observation complements scientific bird-ringing. For example, the migration routes of raptors, including Eastern Buzzards and various sparrowhawks, have been shown by direct observation to run across the straits from southwest Hokkaidō to northwest Honshū, and a major migration route of Chinese Sparrowhawk through the Nansei Shotō was discovered. Although the study of migration through Japan is well advanced, much remains to be learned.

South Polar Skua is the southernmost Southern Hemisphere species to visit Japan [JoH].

1 In this context, migrants are species that pass through Japan between breeding grounds farther north and wintering grounds farther south, but typically neither breed nor winter here.

2 Some species reach Japan occasionally, but not having followed clear migration patterns.

3 In ornithological terms, accidentals (sometimes referred to also as vagrants) are individual birds appearing far away from their normal range. They may be blown by storms, or be far off course because of inappropriate migration instincts.

4 Some occasionally spend the winter here, too.

5 Once it was an abundant breeding species on islands and islets around Hokkaidō. A very small number of pairs currently nests, but only on Teuri-tō.

6 There is evidence to suggest that this population may be a separate, and as yet unnamed species.