Chapter Eight

The Birth of Motion Pictures

Edison studies the film from a home projecting kinetoscope.

One of Edison’s ideas in the late 1880s was to combine sound, using his famous phonograph, with a viewing machine. He gave the photographic and optical parts of the assignment to a new mucker, amateur photographer William Kennedy Laurie Dickson. As team leader, Edison dealt with the electromechanical components of the project.

Thomas Alva Edison’s muckers may have worked hard under their boss, but they also worked in an environment that encouraged creativity and provided them with the materials to experiment. The workers were employed to help Edison develop his ideas and to build and test new devices in his New Jersey laboratory. Dickson’s work with Edison set the standard for motion pictures. For the human eye to be fooled into believing that pictures “move,” it has to see at least 24 pictures per second, each slightly different from the previous one. Photographic glass plates were too thick and heavy to move that quickly through any device, so Dickson arranged for the production of a new invention called “photographic pellicle” (invented by Hannibal Goodwin in 1887). Known as celluloid film, this was a type of plastic that had a coating of photographic chemicals on it.

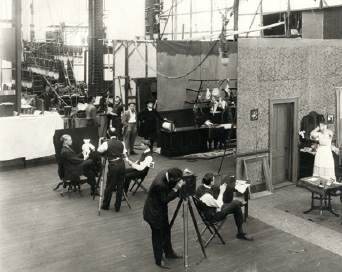

A look at movies being made in Edison’s movie studio in the Bronx, New York.

With his assistant William Heisse, Dickson developed a mechanism that smoothly advanced the film by using sprockets. The sprockets pulled the film forward through perforations on the film’s edges. The film was illuminated by Edison’s electric light bulb. Today, the advancing mechanism, film with perforated edges, and the light bulb still are used in cameras and projectors.

In 1889, the team came up with a working motion picture camera called a kinetograph. A separate viewing device called a kinetoscope followed two years later. Edison filed patents for both machines.

While waiting for the patents to be granted, Edison approved Dickson’s plan to build a studio on Edison’s lot. The “Black Maria” was an odd-shaped, tarpaper-covered building that got its name from the slang term for a type of police wagon that it resembled. Like any camera, the kinetograph required bright light to record images, so the Black Maria’s roof could be cranked open, and the whole building was able to rotate on a track.

The Black Maria was the first movie studio.

In 1893 and 1894, the world’s first true motion pictures were filmed inside the Black Maria. Some starred Dickson; others, like Fred Ott’s Sneeze, starred lab assistants. A succession of trick dogs, dancers, performing bears, knife throwers, and acrobats also were captured on film in the Black Maria.

The kinetoscope debuted at Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. Thousands of people paid 25 cents to peer, one at a time, through the kinetoscope’s eyepiece. Enterprising businessmen bought dozens of kinetoscopes and opened kinetoscope parlors. Soon, though, the novelty of watching one-minute films wore off, and admission prices dropped. When the price to view reached five cents, kinetoscopes became known as nickelodeons.

Edison recognized that the way to make motion pictures profitable was to sell new films, not the devices with which to view them. Dickson, meanwhile, wanted to invent a projection device that let many people at one time watch longer films. When Edison ordered Dickson to put aside projection to make new films, the two men’s working relationship suffered. Their disagreement reached the breaking point in 1895 when inventor Thomas Armat introduced a projection device for kinetographic films. Edison suspected that Dickson had helped Armat. Dickson left Edison’s employment, and Edison purchased Armat’s device. The terms of the sale allowed Edison to manufacture the machine, which he named the Vitascope, as his own invention.

In April 1896, Edison exhibited the Vitascope in New York. For nearly a decade, practically all the motion pictures seen by American audiences were made by Edison. His only real competition came from his former employee. After leaving Edison in 1895, Dickson founded his own motion picture company, which eventually became known as Biograph.

In the early 1900s, though, more competitors arrived on the motion picture scene. Many were unwilling to pay Edison for the right to use his patented equipment. Hoping to avoid Edison’s private detectives and law enforcement agents, some early moviemakers moved all the way across the country to a tiny suburb of Los Angeles, California. There, the agreeable climate offered plenty of year-round natural light, and films could be set in any location, from the water to the desert. In a roundabout way, then, we can say that Edison “invented” Hollywood!

Edison long was regarded as the sole inventor of motion pictures. Today many finally recognize Dickson’s vital contributions. In fact, “The Film 100,” a 1996 list of the most influential people in the history of motion pictures, cites Edison as the 10th most important person in film history. William Kennedy Laurie Dickson is number one.