Chapter Five

Edison’s Baby

The wax cylinders that held the recordings for Edison’s phonograph could be delivered to customers’ doorsteps.

Whenever reporters asked Thomas Edison to name his favorite invention, he always replied, “The phonograph.” It was the only invention he ever referred to as “my baby,” claiming, “This is my baby and I expect it to grow up to be a big feller and support me in my old age.”

Edison had gotten his idea for recording sound while trying to improve on Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, which had been invented one year earlier, in 1876. Edison first concentrated on making a better mouthpiece, or transmitter. While working on that, he thought another improvement might be a machine to record phone messages. Edison already had invented a way to record telegraph messages. Recording sound would prove to be more difficult, but his knowledge of the telephone helped. Edison knew that a telephone transmitter used a diaphragm and an electromagnet to convert sound waves into a pattern of weaker and stronger electrical currents. He also knew that a telephone receiver turned these variations in current back into sound. The telephone’s transmitter and receiver provided Edison with two vital parts of the phonograph.

In addition, Edison borrowed from an invention by Leon Scott. In 1856, Scott had developed a machine that traced the shape of sound waves onto paper. (His was not an attempt to reproduce sound, however. Scott only wanted scientists to be able to “see” sound waves.)

Edison combined and altered these inventions. In his first experiments, Edison spoke into a trumpet that had a thin metal diaphragm at the end. Sound waves made the diaphragm vibrate, and a needle attached to the diaphragm punched a pattern into thick paper tape as it was pulled under the needle. The tape then was pulled under another needle, causing a second diaphragm to reproduce the original sound. Unfortunately, the sound quality of Edison’s first attempt was poor.

Edison found his own dictation machine to be useful.

So, Edison decided to replace the tape with tinfoil wrapped around a cylinder, which could be turned beneath the needles by a hand crank. Edison drew a picture of the machine he had in mind, and one of his assistants, John Kruesi, built it in early December 1877. With Edison reciting the poem “Mary had a little lamb…,” it recorded on the first try!

Edison took his “talking” machine to New York and showed it to the editors of Scientific American. Magazines and newspapers around the world carried the sensational news, and the 30-year-old Edison became an international celebrity.

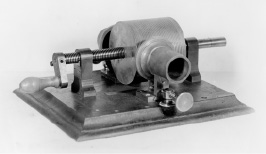

Edison’s original tin-foil phonograph.

Edison soon thought of many uses for his new invention: dictation machines, books for the blind, and musical performances, to name a few. Unfortunately, though, the phonograph still was very crude. Improving it to the point where it could do any of those things well would require many more years of trial and error.

In the meantime, Edison decided he needed a vacation, so he interrupted his work for a long trip out West. Upon his return, Edison’s mind was filled with new ideas. For the next 10 years, he poured all his energy into developing electric light and power stations. It was 1887 before he returned to his work on the phonograph.

When he came back to this project, Edison devoted two years to developing a “new, improved” phonograph. He replaced the tinfoil with a cylinder made of hard wax and added a battery that turned it at a steady speed. These and other improvements made the phonograph easier to operate. In addition, the quality of the sound was much better, and the wax cylinders held a full two minutes of recorded sound.

After that success, however, his first project to employ the science behind the phonograph—talking dolls—was a failure. Edison had hoped the dolls would earn a quick profit. Unfortunately, the tiny phonographs in the dolls often broke before they even arrived at stores.

Edison then planned to sell his phonograph invention as a dictation machine. To his surprise, businesses showed little interest. What people wanted in 1889 were coin-operated phonographs, or jukeboxes.

At first, Edison insisted on pushing his dictation machine idea. But with competitors eager to capture this new phonograph market, Edison entered the music business. And once he did, as with everything else, he became completely involved.

For many years, Edison personally hired all his company’s singers and musicians and decided which recordings would be released. Since he was quite deaf, Edison auditioned recordings by biting the wooden case of the phonograph and “listening,” or feeling the vibrations, through his teeth! Edison’s company produced phonographs and records for 52 years. During that time, Edison and others made thousands of improvements in sound recording and were rewarded with high profits. By 1929, however, they were losing their customers to a newer invention: radio. But by then Edison did not seem to mind. He was 82 years old and completely absorbed in his latest project—searching for a new way to make rubber.