Chapter Six

A Brilliant Idea

Perhaps Edison’s most famous invention was the incandescent light bulb. Before its invention, most homes relied on candlelight, oil lamps, or gas lamps. But, the candle or oil flames caused fires, and the gas was smelly and built up dangerous fumes. So, it was no wonder there was an excited buzz surrounding the display of electric arc lamps (invented by Edward Weston) at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, the lamps—which produced brilliant light as electricity arched or leaped across small gaps between electrodes—emitted an intense glare that was far too bright for home use.

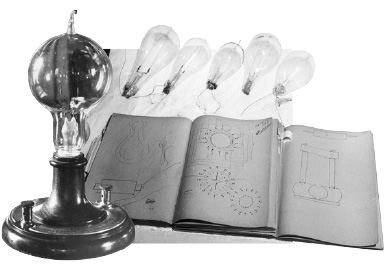

Incandescent light works when an electric current flows through a fine material, called filament, and makes it glow. Thomas Alva Edison’s journals noted that effect in 1876 after some experimentation with carbonized paper. But Edison did not become serious about developing an incandescent light bulb until he vacationed out West in the summer of 1878. A physicist friend, George Barker, encouraged Edison to explore the possibilities of an electric light system.

Upon his return, Edison visited an electric arc light factory in Connecticut. Edison was intrigued by how the owner, William Wallace, made eight lamps glow at once with one generator, or dynamo.

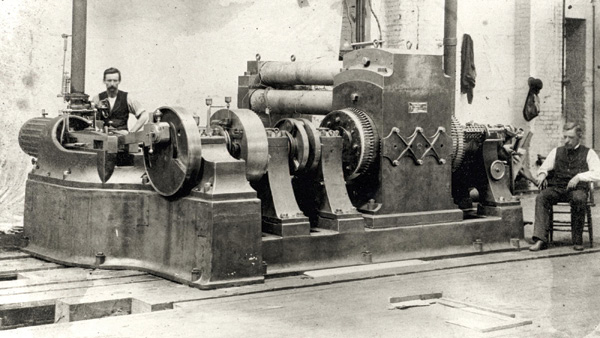

In September 1878 Edison caused a sensation when he declared to the press, “With 15 or 20 of these dynamo-electric machines...I can light the entire lower part of New York City.” He added, “...[T]he same wire that brings the light to you will also bring power and heat.”

Edison’s self-publicity had its desired effect: It attracted financial backers, including financier J.P. Morgan. At their urging, Edison brought on board physics and math expert Francis Upton to lend his knowledge to the project. But actually making a practical and reliable incandescent light bulb took far longer than the “few weeks” Edison originally had predicted.

Finding the right material for the filament turned out to be a huge problem. Edison’s first bulbs used carbonized paper in partial-vacuum jars. They glowed, but for only about eight minutes. Edison and his team then tested various materials until their eyes hurt. They rejected iron, cobalt, nickel, silicon, boron, and others because they either melted or burned out too quickly. Edison decided he needed the thinnest possible filament, and Upton’s math calculations backed that conclusion. A thin filament would raise the electrical resistance, which would let Edison bring down the current. Edison also found a better vacuum pump for the glass bulbs. With less oxygen present, the wires would not be able to burn as easily. Edison found more efficient ways to seal the bulbs and keep the oxygen out, too.

By the spring of 1879, Edison had a light bulb working with a platinum filament. But platinum was very expensive, and the bulb still was not reliable enough. The experiments continued.

A 19th century illustration of how Edison might have carbonized paper while searching for a filament for his light bulb.

While working in the lab one fall evening, Edison abstractedly began playing with a piece of lampblack and tar that was there for the lab’s telephone project. After rolling it into a thin thread, Edison later said that he decided on carbon as his new filament. After all, something that was already carbonized was not likely to burn much more.

But what kind of carbon? Edison’s team tried carbonizing all sorts of things, including wood, fishing line, and even coconut hair. On October 21, 1879, they tried a light bulb with carbonized cotton sewing thread. It glowed for more than 13 hours!

Over the following weeks, the team had even more success with a carbonized cardboard filament shaped like a horseshoe, which glowed for more than 100 hours. News of Edison’s invention became public in December. Crowds thronged to Menlo Park for a special New Year’s Eve demonstration of the new incandescent light bulbs.

Edison had promised to light up lower Manhattan, however, and that took longer. He moved to New York City to be closer to the project, and his group made plans to lay underground electric wires and contract with customers. Finally, on September 4, 1882, Edison’s Pearl Street Power Station lit up about 200 homes and businesses in New York City.

“I have accomplished all I promised,” Edison said.

One of Edison’s jumbo dynamos, used to generate electricity for New York City.

In 1889, Edison’s electric companies joined together as Edison General Electric. After merging with another company in 1892, the company became simply General Electric Corporation, which still exists today.

Over time, alternating current (AC) power systems prevailed over Edison’s direct current (DC) system. And light bulb manufacturers eventually switched to tungsten filaments. But Edison’s incandescent light bulb and his foresight to create an electrical delivery system remain among his brightest inventions.