Beginnings and Reconciliations

A Painful Reality

Loss is a very real part of human experience that may not occur very frequently but can have profound effects on an individual’s life. Loss is something we must learn to accept and cope with. The late anthropologist Margaret Mead said, “When a person is born we rejoice, when they’ve married we jubilate, but when they die we try to pretend that nothing has happened.” This kind of avoidance, a veiling of actual circumstance, has negative consequences for all involved, but especially for those who have experienced the loss.

In our society, it is very difficult to end a relationship after the person has died, and it is difficult to end a relationship that itself has died. The cost of our personal commitment, the “price of love,”1 is grief, which has negative consequences in the lives of those involved. And yet, loss and grief can also lead to positive change and growth in a person’s life.

After we lose someone or something close to us—whether through death, divorce, separation, or retirement—we feel the cost of that commitment. Those costs can be high, and they can be very challenging. Sickness, anxiety, anger, depression, and even death can occur after we suffer a major loss. But this does not necessarily have to be the outcome. What can we do to cope with our loss? How do we center ourselves again, learn to live again, albeit differently and in the absence of the one or thing we loved?

The Journey through Grief—A Review

The process of grief, whether from the loss of someone you love, loss of a job or career, or some other type of loss, entails a similar range of experiences that are not bound to prescribed phases or stages or even time lines. Various approaches and the arguments against them have been outlined in earlier chapters of this book. But grief has a look to it and a certain face that does have some commonality.

There is that first psychological state of shock at hearing the news of the death of a loved one, but also the sudden realization that something has actually ended, and with that a certain numbness and unreality of a life now changed. We seem swallowed in our emotions; our behaviors seem rote and mechanical; and we seem to have limited memory of conversations or discussions that have occurred with other people. This state of shock is normal and generally passes quickly, although the reality of absence soon seeps in. The very strong and very real feelings that come with loss are extremely intense—and more than frightening. The numbness that everyone experiences following a major loss is the mind’s way of letting one deal with all of the details that surround the loss. Numbness allows our body and mind to process the details. It gives us a much-needed time-out. How long that lasts is generally up to us. During this time, we may feel distant and disconnected, even from ourselves. And sometimes this leads people to believe that we are under control. In reality, the finality of our loss has not yet been fully felt. The body begins to process loss bit by bit.

After a few weeks, another set of experiences will be triggered by feelings of emptiness and the permanence of loss. Our sense of pain and abandonment can lead to loss of appetite, sleep, and overwhelming depression. These feelings are perfectly normal, and they are vitally necessary to continue to cope. The best thing to do at this time is to loosen inhibitions and emotions to their fullest. Painful as they are, acknowledging their existence is the first step toward alleviating them. It may look like backsliding, but it is not. Persistent weeping, lack of focus, apathy, and black depression are all positive signs at this time, for they show that one is accepting the reality of what has happened—a normal reaction to loss. At this time, belongings of the deceased can be intense painful reminders of the loss. It is not uncommon for the bereaved to want to look at photographs or videos of the deceased. Thinking that one sees or hears the deceased is also common. We may feel like we are going crazy, but we’re not. True mental illness is relatively permanent, whereas these grief behaviors are transient, and they will pass as one begins to cope with grief. Feelings of anger may also surface at this time, creating further confusion, but why not? One has been left alone, deserted, without one’s most important system support system, especially if the loss has been a spouse. It is logical for the bereaved to feel angry with the one who has departed. And although this anger is natural, and almost inevitable, feeling guilty about one’s anger is also natural—but unhealthy, if the guilt persists.

Recognizing and acknowledging our feelings about loss is what distinguishes us as human beings. Our feelings eventually provide us strength to endure and move forward. There is no real time line for this because each person is different precisely because each person’s life context is different. Research used to tell us that the degree of attachment to the deceased or the thing lost influenced the duration of our grief, but some now dispute this claim altogether, arguing that an individual’s resilience is a much more important factor influencing how one grieves and how one copes (Doka, 2016). Recognizing our own “grief experience,” helps us to situate ourselves within this common human experience. It allows us to organize our feelings into coherent and manageable pieces so that, as bereaved, we can feel some control, safety, and a sense that overcoming our grief is an achievable, if not inevitable, process. We understand that it will take some time. We just don’t know how much.

For women, who have an innate sense of caregiving and nurturing, this uncertainty is unsettling.

The first signs that a person is dealing successfully with her pain may at first be slight, but any sign, however small, is a major accomplishment, and she should feel good about this success. Again, a day spent without experiencing pain followed by a very painful day does not indicate backsliding, but only the unpredictability associated with the period of recovery. Congratulations for every good hour are well in order, however many hours that may be.

Understanding the different aspects of grief can be instrumental in realizing that one is normal and that it is okay to feel the intense emotions that grief calls forward. What is significant is that although this pain may feel like it exists only in the mind, a very real and present danger exists for the body. The bereaved are under tremendous stress, and the body feels it. Loss of appetite, loss of sleep, and apathy can be very harmful to one’s overall well-being.

Grief can affect weight gain and weight loss, and both can cause health problems and an even further lowering of self-esteem. A healthy diet may seem like the last thing that one should be worried about when a significant loss occurs, but one’s level of health inevitably reflects on how well and how fast one recovers from loss. Depression, anxiety, anger, guilt, and loneliness all have a severe impact on the eating habits of the bereaved, so a diet rich in protein is important.

Exercise too is a very important aspect of recovery. Muscles that are utilized and healthy circulatory and respiratory systems make people feel better in many ways, and most importantly, exercise supports positive self-esteem. It is not important to run a marathon or lift heavy weights; each individual is different and has different needs. It is only important to remain active physically whether this activity takes the form of running, swimming, or walking the dog. It is very important that one does not cease physical activity when mourning a loss. Being active is part of expressing individuality, and cessation of physical activity can mean a further loss of self-esteem. Survivors need to help themselves through meeting their nutritional and physical needs, even though these may seem the very least important things to attend to at the time of loss.

Loss of sleep is often a sign of depression and a sign that the individual is suffering. Getting enough sleep is critical. Realizing that we are our own most important resource and focusing on health matters helps us to develop a close, intimate relationship with ourselves—especially during the difficult time of loss when it is extremely important to have a well-developed sense of self. Intense introspection is the only thing that can bring the individual survivor of loss to the point of understanding what that loss means in our life, and learning what works to incorporate that loss into our life is what helps us to move forward with self-awareness and self-confidence. These are important milestones in coping with loss and integrating loss into a new life pattern.

The Individuality of a Woman’s Grief Experience

In this book, we have focused on building a better understanding of women’s grief—not because it is so completely different from a man’s grief, but because there are social and cultural influences that have made the loss and grief experience for women remarkable in some ways, and it is those experiences that we have tried to illuminate.

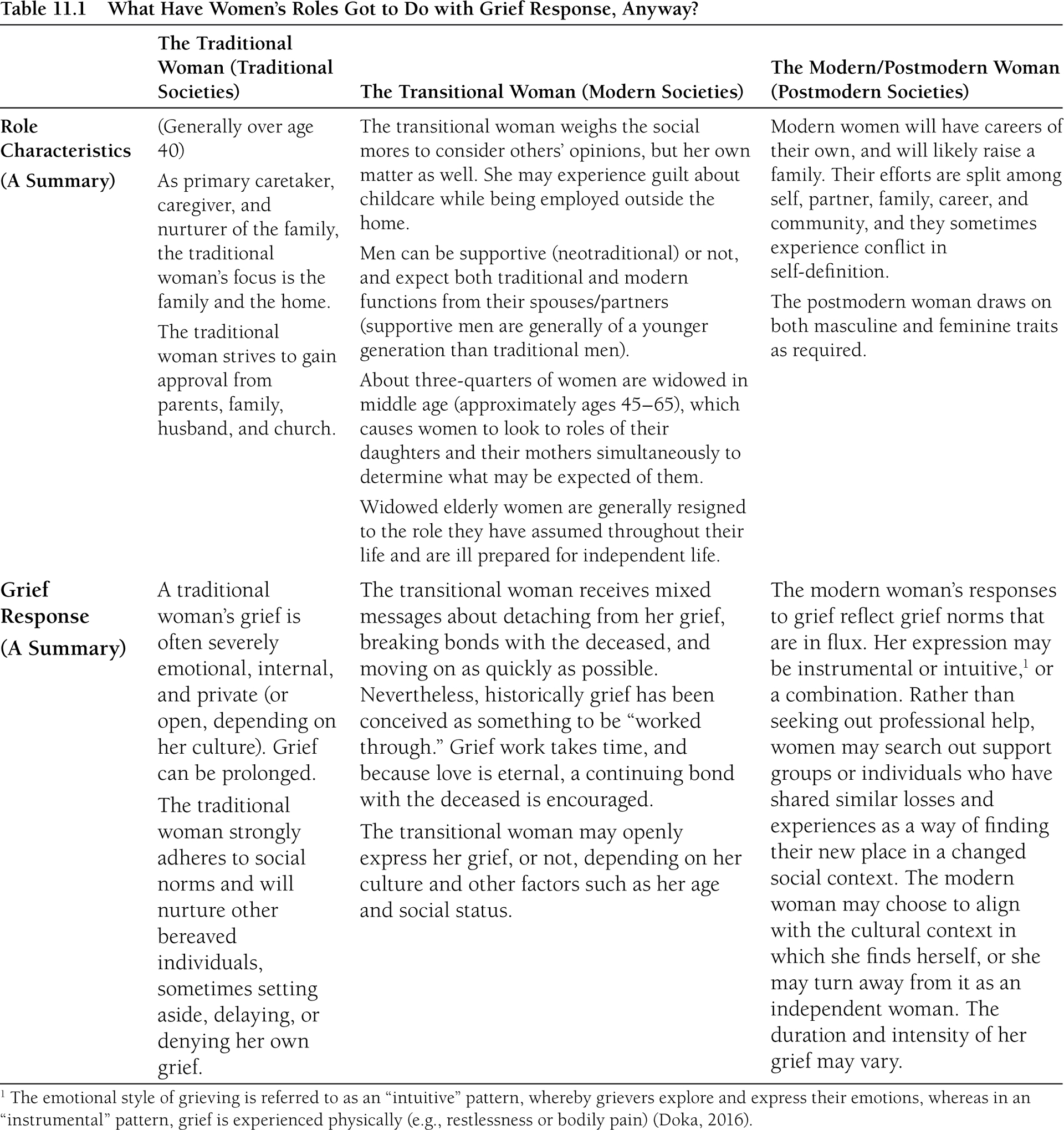

In the first two chapters, the social construction of the roles of women (traditional, transitional, modern/postmodern) was explicated in light of a historical look at how grief has been conceptualized and addressed over time. Those insights help us to better understand how women may respond to grief differently, not only because of their age, education level, and financial and social status but because of the critically important sociocultural environment in which the woman was raised and how she functions in her current situation.

A woman’s response to loss and grief is influenced by the depth of grief she feels within the context of her life. It is not that grief defines her. It is that she defines her life within—and perhaps in spite of the loss and grief she experiences and the extent to which she integrates that absence into her continuing life journey. Women’s experiences of loss and grief can be very complex, and for many women it is a difficult journey and a difficult story to tell—particularly for women of the baby boomer generation who are now reaching their 60s and 70s. Many of these women were raised in traditional households, where grief was felt and expressed privately and where one just carried on in spite of the lead in one’s heart.

For women who have been socialized into a traditional role of caregiving and dependency, a traditional grief response can be expected (Gilligan, 1993; Pipher, 1994). However, because of the growing number of women who are now well educated, with careers of their own (many living independent, single lives and sometimes raising children on their own as well), a grief response that is more reflective of a modern/postmodern woman is becoming more common. As well, women who are younger and who have been raised in modern/postmodern households and societies may experience their partners (usually male) as being more “empathic, egalitarian and sensitive” (Pollack, 1998). These combined factors are changing the complexion of women’s grief response—to say nothing of the multicultural influences on both the ways girls and young women are raised and the manner in which they are expected to respond within the boundaries of their particular social and cultural relationships with the males in their lives (i.e., spouses/partners, fathers, brothers, cousins, etc.) and/or significant others of any gender orientation. In short, the culture shaping women’s grief is inevitably in transition itself, making any set pattern or expectation of response both unrealistic and ill advised. Nevertheless, for now, and in light of a burgeoning older population of women at hand, the following reference points do provide a way to think about what a woman’s experience of loss and grief may look like.

Healthy Expression of Grief

There are varying views on expressions of grief. One view, which we support in this book, is that open expression of grief is much healthier than holding it inside or denying it altogether. Denial is an unconscious psychological defense related to the social norm that individuals always appear “cool, calm, and collected.” The reality is that there are many times when human experience is anything but “calm.” People are taught to be strong and in control, but often this involves a false sense of strength. The true sign of strength is the ability to express actual feelings, not deny or suppress them. Emotions are not weaknesses. They are not lesser than reason and do not show weak lapses in self-control. They are a legitimate part of experience, just as masculine and feminine traits are a legitimate part of our human characteristics and potentialities.

If sadness is experienced, it is important to cry. If anger is felt, beating on a mattress with a broom, jumping up and down, or yelling aloud are all helpful. Release of extreme emotional tension will help the survivor feel much better.2 Destructive behavior such as breaking furniture or windows will only create worse feelings later and will destroy any benefits gained.

It is unfortunate in the Western world that showing emotion is perceived as weakness when, in fact, it takes a good deal of strength to let oneself express strong emotions. Probably the most helpful change that could take place to assist survivors of loss would be a change in how our society values masculine and feminine characteristics. Qualities traditionally associated with the masculine, such as aggressiveness, competitiveness, and rigid suppression of anything that is not strictly “rational,” have traditionally been valued more highly than have feminine qualities, such as warmth, expressiveness, and caring. That these feminine qualities have been consistently derided and seen as weak is directly related to the difficulty survivors of loss have in progressing through the grieving process. A reevaluation of the masculine and feminine and an increased awareness that these qualities that are indigenous to all human beings, irrespective of biological sex, would be extremely beneficial to both the individual experiencing grief and to societies as a whole—particularly in a world where the masculine ethic of aggression has forced people everywhere through the devastation of two World Wars and now terrorism on a global scale. Both masculine and feminine qualities are valuable and necessary. A widespread acceptance of the integration of the masculine and feminine would help each of us to experience a more healthy grieving process.

Research supports this view. “Intuitive” responses to grief (i.e., through expressing and exploring emotions, commonly ascribed to a feminine response pattern) and “instrumental,” or more physical, expression through restlessness or bodily pain, where one “thinks through” or “acts” out grief, commonly ascribed to a more masculine response pattern (Doka, 2016), are both considered effective coping strategies (Doka and Martin, 2010).3 Importantly, how one grieves and the intensity of the grief response bear no relation to the depth to which one loved the person or the thing lost (Doka, 2016).

Grief as Opportunity for Change and Growth

For survivors to get themselves back into emotional, physical, psychological, and spiritual balance, relying on oneself as their greatest resource can be uplifting and immensely valuable. No one can specify how a person should or should not feel at a particular point in the grieving process, and no one can know exactly what is going on inside the bereaved’s mind or heart. One of the most important things a survivor of loss can do, or that anyone else can do to help stabilize and improve the survivor’s self-esteem, is to shift the locus of control from others to the self. Accepting the opinions of others as fact can be very damaging and can seriously impede personal progress. Family and friends can be a great help to the survivor of loss, but only those who have experienced grief can truly understand the situation, and these are people to whom a survivor can turn for support. The survivor will have a myriad of questions, which require honest answers, and others who have similar experiences can answer some of them. Survivors should know that they are not alone in their feelings and that their feelings are normal. Culturally and spiritually supportive community support groups can offer specific and directed counseling as required.

The process of grief is not easy and may in fact be the most stressful and painful time in a person’s life. However, loss initiates change, and it is up to each individual to decide the form that change will take. Loss can sometimes work as a starting point from which to consciously change many destructive behavioral patterns such as letting the locus of individual self-esteem center on others (as in a traditional role). Loss is never a pleasant experience, but it can form the basis for a way of living through active, conscious choice controlled by the thoughts and actions of the individual herself. Living in the present initiates one into an awareness of the positive within oneself, an awareness which is empowering and which acts as a catalyst for potential growth. For women who survive their spouses (or partners), Naomi Golan (1983) describes recovery as moving from wife to widow, to woman—a kind of metamorphosis in which the change created by the loss initiates a form of search for the self. This search involves a strong will and a personal commitment to accepting change—discovering who and what are happiest being and doing, and consciously moving to sustain this in our lives. Taking active control of our own life and living according to our own decisions is a possible and positive outcome of the grieving process for women that is highly enabling—emotionally, physically, psychologically, and spiritually. We encourage women to seek this growth through their grief, regardless of the sociocultural environment in which they were raised or in which they currently live.

Notes

1. K. Doka (2016), Grief Is a Journey (New York: Atria Books). Also, C. Parkes (2015), The Price of Love: The Selected Works of Colin Murray Parkes (New York: Routledge).

2. Keeping a journal can assist survivors of loss to understand and come to terms with the various complex and often conflicting emotions accompanying grief. Recording feelings, along with their strength and frequency, can help survivors to organize their feelings and observe their own progress over time. For example, one might write, “Today I feel terribly empty,” and that might be all. Time spent writing is important because it is also time spent thinking, and because loss often engenders confusion, the writing process, itself can help to clarify and sort through. The reflective process often leads the survivor to question their values and society’s values as well—perhaps for the first time. Survivors may also question the validity of their religion or their purpose in life, and even the value of life itself. These wonderings are normal, and although answers will not come easily or quickly, it lies within the capacity of each individual to come to terms with these questions in a workable way as part of reframing self-identity.

3. Not displaying emotions such as crying (historically regarded as an inability to grieve) or not dealing with grief, especially in Western world culture, may have been derived from a grief myth that Doka refers to as “an affective bias” in counseling, particularly as it applies to men and grief (i.e., men are perceived to be less likely to show emotion or accept help, and as having more difficulty responding to loss) (Doka, 2016). Coping through open expression is one way (an intuitive pattern), as is physical expression of grief through doing or thinking (an instrumental form of expression).