April 1844

From his university days, George Lewis (1803–1879) identified with the evangelical wing of the Church of Scotland. He taught economics and edited a church-related newspaper before beginning his active ministry. When the Church of Scotland split in 1843, a third of the ministers and half the members left the established state church; Lewis took his congregation into the evangelical Free Church of Scotland. The new church, not having state support, immediately began raising funds elsewhere in Great Britain and in the North America. For six months in 1843–44, Lewis was part of a deputation that toured Canada and the United States to raise funds for the Free Church. Although this trip was financially successful, including raising monies from slave owners, his outspoken anti-slavery position caused controversy in the South. Impressions of America confirmed his spoken views. Furthermore, those who raised funds in slave-holding states were widely criticized—including by Frederick Douglass—and were encouraged to return the “blood-stained” donations and to break communion with churches in slave-holding states.

In Scotland, Lewis had long worked to alleviate the urban poverty and ignorance of industrial workers. Because of lack of success in this endeavor, Lewis eventually left his urban parish and abandoned his belief that British factory conditions could be improved by moral means. Subsequently, he retreated to a rural parish where he devoted his efforts to raising his five daughters.

Lewis was interested in the Presbyterian Church in America, as well as education, slavery, American labor conditions, and Scottish emigrants. Within these limits, Lewis’s Impressions of America presents a very credible, informative account.

George Lewis, Impressions of America and the American Churches: From Journal of the Rev. G. Lewis (Edinburgh: W. P. Kennedy, 1845), 155–163.

I arrived in Montgomery, Alabama, about midnight on the 9th April, after three days and three nights staging, feverish and nervous from want of sleep and exercise, but found relief by the luxury of a bath and a sound sleep, and arose grateful to God for his protection over me throughout my journey. Inquiring for the Presbyterian minister, I found his carriage at the corner of the street. He received me cordially, and drove me for the night to his house, about a mile from the town. The prairies of Alabama begin but a little way out of the town—some woodland, others without any wood. Half a mile from his house, we came to one of the woodland prairies, where the sand ceases, and a rotten limestone, mixed with vegetable matter, forms a warm, rich, and very deep soil. The aspect and colour of the soil is very different from any I have lately passed through. Here there is a run of twenty miles of this fertile soil. Twenty years ago this land was sold at the State price of a dollar and a-half; now it is worth fifty dollars an acre.[2] The chief want in the prairies, in summer, is water; the surface wells all drying up. This has caused some of the wealthier settlers to form artesian wells, at the depth of some hundred feet, which they put down by augers or bores, about the diameter of your arm, and which at all seasons sends forth a stream of water, pure and cool. The wood of the Alabama prairies is all young and recent, having no appearance of antiquity. The trees are scattered over the meadow, forming ornaments rather than covers; and, by preserving the ground in some measure from the scorching sun, allow the rich pasture to spring up. Montgomery, as a town, is only twenty-five years old, having passed in that period from log-houses to frame-houses, and from frame-houses to brick, and now numbers 4,000 inhabitants.

The State of Alabama is 317 miles long, and 174 broad, containing about 28,160,000 acres. It lies between 30 and 35 degrees of north latitude, having the Gulf of Mexico and the Floridas on the south—Georgia on the east—the State of Tennesee on the north, and Mississippi on the west. The population has increased since 1810 as follows:—

1810 10,000

1814 29,683

1818 70,544

1820 127,901

1827 244,041

1830 308,997

1840 590,756

of this last number, 253,532 are slaves. The free coloured persons, male and female, are only 2,039. (Manummitted slaves cannot remain after manumission.) The rich prairies occupy the central part. The rest is rather hilly, and the banks of the rivers are said to be unhealthy. In 1840, the exports of this State amounted to nearly thirteen millions of dollars. It has three daily newspapers, and twenty-four weekly. The University of Alabama, which is liberally endowed by the State, I did not see. It is at Tuscaloosa, and was founded in 1820. In it, and Grange College, in the county of Franklin, the students do not exceed 152. The educational returns in 1840, give 114 academies, or grammar schools, with 5,018 scholars and 639 primary or common schools, with 16,243 scholars, which gives a twenty-third of the population at school, including the coloured people, or about a twelfth part, excluding those whom this State jealously exclude from the benefits of education, lest it should endanger their property and power over their fellow-men. The educational returns report not less than 22,592 persons, above twenty years of age, unable to read or write. This, no doubt, is the lowest, and not the highest number, indicating a very low state of education amongst the white population, compared with the northern or eastern States.

The Baptists report that they have in Alabama 250 churches; but, as they have only 109 ministers, these churches must be mere preaching stations. They have 11,445 communicants or members, which gives 105 members to each minister, or forty-five to each congregation. The Methodists have sixty ministers, and 13,845 members, or 231 members to each minister. The Presbyterians, twenty-five churches, and twenty-nine ministers, and 2,268 members, most of their churches being as yet only stations for preaching. The Roman Catholics have a bishop and five priests, and the Episcopalians seven ministers, but I could not learn the state of their congregations. Every thing in this State is in its infancy, and it were a healthy promising infancy but for slavery. Even here railways are to be found. The Alabama and Florida railway extends from Pentacola, 156½ miles, to Montgomery and cost 2,500,000 dollars, and has a branch extending ten miles, from Selma to Cahawba. Most of this State was originally included in the territory of Georgia; but Georgia ceded her rights, and it was admitted into the Union in 1820 [1819].

The residence of the Presbyterian minister of Montgomery is not unlike a Scottish manse and glebe. House and grounds are, however, his own purchase, which he obtained, house and seventeen acres of the finest land, surrounded by a grove, for 1,500 dollars, about £300. Both he and his lady are from the neighbouring State of Georgia. His congregation is small, only eighty members, 250 sitters. The ladies of the congregation are at present working hard to erect a new church, and have got 1,000 dollars gathered by fancy fairs and suppers, at which they preside—thus drawing the world to help the church, means to which the church would never need to resort, if each of its members felt more the duty and privilege of aiding the cause of Christ with their substance. Let not those blame the Church for resorting to these arts, who, when applied to for aid, contribute a less sum to the cause of Christ than they spend weekly upon their meanest pleasures.

We had got into a pleasant conversation upon Scotland, and America, and Presbyterianism, &c., when the minister’s only child would not take its tea, and began to look a little flushed. A mother’s fears interpreted the symptoms into the beginning of scarlet fever. I ventured to hint that the child might have eaten too much, and that it should be suffered quietly to sleep it over, as it seemed quite disposed to do; but no! the little fellow must take his tea, which, with a full soul, he would have loathed, though it had been honeycomb—and so we had a scene, or succession of scenes. The child screamed itself into a fever, and I quite lost favour in the eyes of the lady by advocating the let-alone system, that nature might get time to work herself right. Scotland, America, and Presbyterianism were all forgotten, and I was quickly despatched to bed. In the morning the signs of scarlet fever, and every other kind of fever but the hunger fever, were gone. The lady had recovered her good humour. She said with a good humoured smile, “We loved so to talk about the Kirk.” “It is our sick child,” said I.

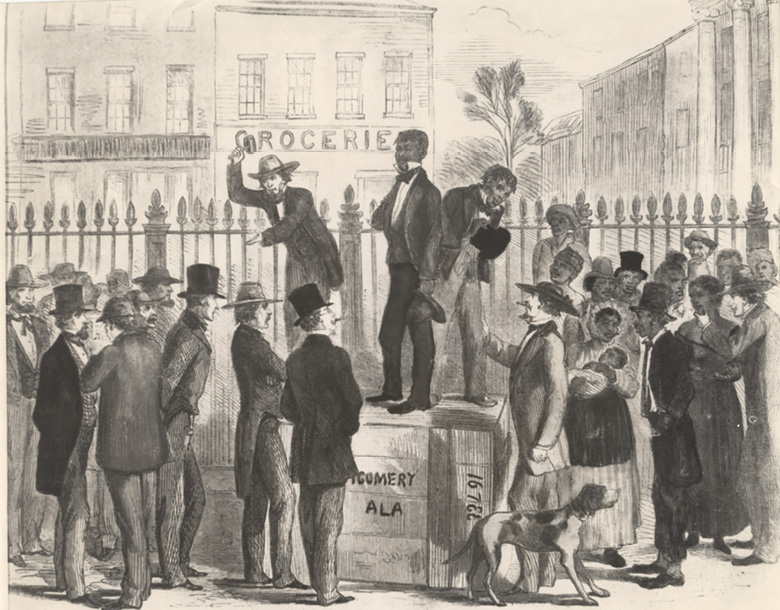

On leaving Montgomery, we drove past the Town-house, in front of which was seated a band of young negroes and negresses, all under twenty years of age. There were not fewer than fifty, the one half females, sitting on one side, and the young men on the other. They looked so neat and clean, and their clothes so new and shining, that my first thought was that they were charity children dressed for some holiday scene. “What’s this?” I exclaimed. “I am ashamed to say that is our slave market,” was the reply. “They are decked out to attract customers.” None of them was chained. They sat silent and demure—too silent and demure for holiday children. The salesman sat in the middle, rocking on a chair, balanced on its hind feet, his heels thrown upwards against a railing, and a newspaper in his hand. No one seemed at the time inquiring their price, but it was early, ere business had well begun. Such public exhibitions are still very common here, though no longer permitted in the Carolinas. I asked if they were field labourers, or domestic slaves, and learned that they were all field labourers. Their present dress is only for days of sale, and has been worn by many hundred young men and women in succession, who have gone through the same exhibition, like any other live stock tricked out for the market. As soon as sold, they are stripped of their ornaments, and reduced to their every day rags. We soon saw the truth of this in the appearance of a family of field labourers just dropped from a waggon, and standing in the streets half naked, whose single ragged garment of linen could hardly be detected to have been once of a white colour. That the law does occasionally, in this State, afford some protection to the poor slave in extreme cases, I am glad to learn. A planter in this neighbourhood was fined 10,000 dollars, some short time ago, for starving his slaves.

Newspaper illustration of “Slave Auction in Montgomery, Alabama.”

The household slaves I saw seemed to be lazy, and unserviceable. They did not come at the call of their mistress or master, took their own time, and were averse to any kind of work, out of the ordinary routine. The State of Alabama, by forbidding the manumitted slave to remain in the State in which he has been born and bred, and where all his earthly affections and interests are centred, has extinguished all hope and desire in the breast of the coloured population to better their condition, by services, however faithful and prolonged. The same act by which they have rivetted the chain, has rendered the slave a worse servant, and lowered his value to his master as a bondsman. As well destroy the mainspring of our watches, and expect the hands to point the right time, as take away hope and expect faithful service from human beings. If a manumitted slave is found in the State, he is sold for the benefit of the State. Thus does the tyrant majority act towards the minority, whose temporal destiny is in their hands, expecting to gather where they have not strawed, and by degrading their labourers, degrading themselves and their children, and retarding the permanent prosperity of their country, for the sake of their immediate interests, and to allay their present fears. Slave labour is only profitable when cotton is high priced. The fall of cotton, by the opening of new markets, would render slave labour more and more unprofitable, and make more obvious the impolicy as well as the inhumanity of slavery, in its immediate effects on their interests. The cultivation of cotton, like that of ”, is individual wealth and general poverty. Herds and flocks, and grain crops, are all forgotten in the growth of cotton or sugar; even, as in South America, no one thought of the greater riches to be procured from the surface of the soil, while anything was to be got by searching for the precious metals in the bowels of the earth. The low price of cotton in Alabama, while it would impoverish many of the present planters, and deprive them of their large returns for a few years, would ultimately enrich the country by an increased production of all the grains and fruits by which a nation multiplies those internal resources which no changes in commerce or in prices can permanently affect.

CHAPTER VII.

. . . We found a steamer from Montgomery to Mobile on the 12th April. The River Alabama, on which we sail, exhibits at the landing place the character of its floods. The river is no more than 100 feet below the banks, which it has excavated and hollowed out by its violence. The last year’s flood has made serious inroads upon the foundations of a vast cotton store, which probably next flood will wholly undermine. At present the river is almost too low to admit of steam navigation, and this is amongst the last trips for the season from Montgomery to Mobile. The steamer is a long slender vessel, having a vast saloon running along its centre, divided into two compartments—that nearest the bow for the gentlemen, also used for dining, and that nearest the stern, being the remotest from the engine, for the ladies, who remain apart throughout the voyage, unless at meals, when they occupy the upper seats, not mingled with, but separated from the gentlemen, who sit lower down, unless they have ladies under their protection, when they sit next them, if they so choose, which they seldom, however, appear to do. The sleeping berths run along each side of this great saloon, and have two doors, one entering from the saloon, and the other from the open air; and by this management, whenever the vessel is in motion, a current of air is supplied by the two doors when open in whole or in part. Meanwhile you are safely secured in a recess from the current, which keeps the apartment sweet and comfortable in hot weather, without exposing you to its full draught. Nothing can be better contrived for this climate than these berths with their double doors. These vessels are very slightly built, and last only four or five years, but will sometimes pay in a single season.

[2] Roughly equivalent to $37 and $1,232, respectively, in today’s currency.