March 1853

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903), born in Connecticut, entered Yale College, but left after a semester. It was not formal education that made the man; rather it was travel—a year’s voyage to China in his mid-teens, as well as three European visits—a six-month walking tour of Great Britain and months in Italy, Germany, and France. His observations resulted in newspaper articles, books, and a budding interest in landscape design, which would in time lead to his becoming the father of American landscape architecture.

In 1852, Olmsted made the first of two visits to the American South; in all, he spent a full year in the South. Sixty-four of his letters were published by the predecessor of today’s New York Times. Subsequently, they were revised and published in three volumes, and even later as The Cotton Kingdom. His published works differ from the norm of travel writing on the antebellum South in that he did not merely report his observations with a few editorial comments, but he actually analyzed the South and found it wanting. Holding democratic ideals, Olmsted worked to elevate the North’s popular culture. He believed that an improvement in Northern taste and morals would prove a free-labor society’s superiority to a slave-labor society. His approach took several paths: editing Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, which published work by Melville and Thoreau, as well an antislavery pieces. Olmsted also supported other antislavery publications, and raised funds to arm Kansas free soilers. Also, before the Civil War, Olmsted became the superintendent of New York City’s Central Park—a naturalistic park that he and Calvert Vaux conceived and designed. He left this position at the beginning of the war to serve as chief executive officer of the U.S. Army’s Sanitary Commission. This did not prove satisfactory, so Olmsted spent the last two years of the war in California dedicated to a variety of landscape projects, including designing the campus at Berkeley and San Francisco’s public parks system, and serving as chairman of the Yosemite Valley Commission. At the end of the war, he returned to New York where he resumed work on the city’s parks. Olmsted believed that not only the South and West required reinventing but so too did New York City, which was in need of civilization most of all.

Of the observers of the antebellum South, Olmsted ranks as one of the most astute, especially of the rural South and the yeoman farmers with whom he sympathized. He was ahead of his time to reject the idea of Southern white solidarity. During some of his travels by horseback, he had opportunities not available to those traveling by coach and steamboat. His personal observations were supplemented by wide reading, from government reports to local histories. A moderate man, he opposed slavery, but not to the extent that he wished to punish the South. Rather, he advocated gradual emancipation; in time, however, Olmsted became more critical of slavery, the general backwardness in the South, and the Southern elite. From a purely economic position, he calculated that a slave did approximately an eighth of the work of the best white laborer. In addition to slaves, he sympathized with poor Southern whites, who he judged to be lower than the lowest Northern classes, except those in the slums of New York City.

The following passage’s confused chronology is the result of augmenting and transferring information from letters.

Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States,with Remarks on Their Economy (New York: Dix and Edwards, 1856), 549–565 and 574–577.

A day’s journey took me from Columbus, through a hilly wilderness, with a few dreary villages, and many isolated cotton farms, with comfortless habitations for black and white upon them, to Montgomery, the capital of Alabama.

Montgomery is a prosperous town, with very pleasant suburbs, and a remarkably enterprising population, among which there is a considerable proportion of Northern and foreign-born business-men and mechanics.

I spent a week here very pleasantly, and then left for Mobile, on the steamboat Fashion, a clean and well-ordered boat, with polite and obliging officers. We were two days and a half making the passage, the boat stopping at almost every bluff and landing to take on cotton, until she had a freight of nineteen hundred bales, which was built up on the guards, seven or eight tiers in hight, and until it reached the hurricane deck. The boat was thus brought so deep that her guards were in the water, and the ripple of the river constantly washed over them. There are two hundred landings on the Alabama river, and three hundred on the Bigby (Tombeckbee of the geographers), at which the boats advertise to call, if required, for passengers or freight. This, of course, makes the passage exceedingly tedious.

The principal town at which we landed was Selma, a thriving and pleasant place, situated upon the most perfectly level natural plain I ever saw. In one corner of the town, while rambling on shore, I came upon a tall, ill-proportioned, broken-windowed brick barrack; it had no grounds about it, was close upon the highway, was in every way dirty, neglected, and forlorn in expression. I inquired what it was, and was informed, the “ Young Ladies’ College.” There were a number of pretty private gardens in the town, in which I noticed several evergreen oaks, the first I had seen since leaving Savannah.

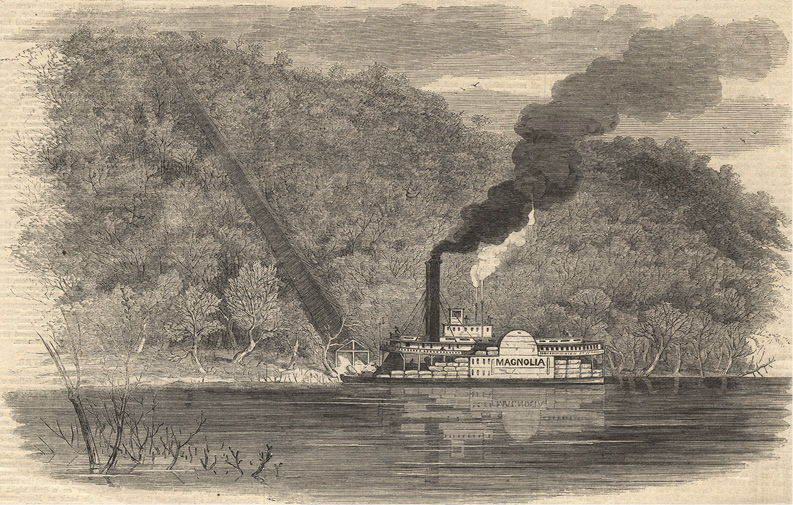

At Claiborne, another considerable village upon the river, we landed, at nine o’clock on a Sunday night. It is situated upon a bluff, a hundred and fifty feet high, with a nearly perpendicular bank, upon the river. The boat came to the shore at the foot of a plank slide-way, down which cotton was sent to it, from a warehouse at the top.

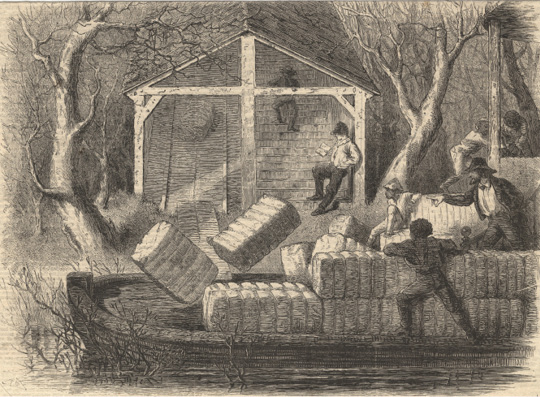

“Cotton-Shoot on the Alabama.” Loading cotton onto the steamboat Magnolia on the Alabama River from the Illustrated London News, 4 May 1861. This is the reverse image of the engraving printed in Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, 21 April 1855. The three-hundred-foot long shoot descends from the two-hundred-foot hill to the river. Above: “Foot of the Shoot: Receiving the Cotton-Bales on Board the Steamer.” Loading cotton onto the steamboat Magnolia on the Alabama River from the Illustrated London News, 4 May 1861. The shoot is divided in half. On one side is the cotton shoot itself, and on the other are the steps.

There was something truly Western in the direct, reckless way in which the boat was loaded. A strong gang-plank being placed at right angles to the slide-way, a bale of cotton was let slide from the top, and, coming down with fearful velocity, on striking the gang-plank, it would rebound up and out on to the boat, against a barricade of bales previously arranged to receive it. The moment it struck this barricade, it would be dashed at by two or three men, and jerked out of the way, and others would roll it to its place for the voyage, on the tiers aft. The mate, standing near the bottom of the slide, as soon as the men had removed one bale to what he thought a safe distance, would shout to those aloft, and down would come another. Not unfrequently, a bale would not strike fairly on its end, and would rebound off, diagonally, overboard; or would be thrown up with such force as to go over the barricade, breaking stanchions and railings, and scattering the passengers on the berth deck. Negro hands were sent to the top of the bank, to roll the bales to the side, and Irishmen were kept below to remove them, and stow them. On asking the mate (with some surmisings) the reason of this arrangement, he said “The niggers are worth too much to be risked here; if the Paddies are knocked overboard, or get their backs broke, nobody loses anything!”

The boat being detained the greater part of the night, and the bounding bales making too much noise to allow me to sleep, I ascended the bank by a flight of two hundred steps, placed by the side of the slide-way, and took a walk in the village. In the principal street, I came upon a group of seven negroes, talking in lively, pleasant tones: presently, one of them commenced to sing, and in a few moments all the others joined in, taking different parts, singing with great skill and taste—better than I ever heard a group of young men in a Northern village, without previous arrangement, but much as I have heard a strolling party of young soldiers, or a company of students, or apprentices, in the streets of a German town, at night. After concluding the song, which was of a sentimental character, and probably had been learned at a concert or theatre, in the village, they continued in conversation, till one of them began to whistle: in a few moments all joined in, taking several different parts, as before, and making a peculiarly plaintive music. Soon after this, they walked all together, singing, and talking soberly, by turns, slowly away. I allowed them to pass me, but kept near them, until they reached a cabin, in the outskirts of the village. Stopping near this a few minutes, two of them danced the “juba,” while the rest whistled and applauded. After some further chat, one said to the rest: “Come, gentlemen, let’s go in and see the ladies,” opening the door of the cabin. They entered, and were received by three negro girls, with great heartiness; then all found seats on beds. and stools, and chests, around a great wood fire, and when I passed again, in a few minutes, they were again singing.

THE MUSICAL TALENT OF NEGROES.

The love of music which characterizes the negro, the readiness with which he acquires skill in the art, his power of memorizing and improvising music is most marked and constant. I think, also, that sweet musical voices are more common with the negro than with the white race—certainly than with the white race in America. I have frequently been startled by clear, bell-like tones, from a negro woman in conversation, while walking the streets of a Southern town, and have listened to them with a thrill of pleasure. A gentleman in Savannah told me that, in the morning after the performance of an opera in that city, he had heard more than one negro, who could in no way have heard it before, whistling the most difficult airs, with perfect accuracy. I have heard ladies say that, whenever they have obtained any new and choice music, almost as soon as they had learned it themselves, their servants would have caught the air, and they were likely to hear it whistled in the streets, the first night they were out. In all of the Southern cities, there are music bands, composed of negroes, often of great excellence. The military parades are usually accompanied by a negro brass band.

Dr. Cartwright, arguing that the negro is a race of inferior capabilities, says that the negro does not understand harmony; his songs are mere sounds, without sense or meaning. My observations are of but little value upon such a point, as I have had no musical education; but they would lead me to the contrary opinion. The common plantation-negroes, or deck-hands of the steamboats—whose minds are so little cultivated that they cannot count twenty—will often, in rolling cotton-bales, or carrying wood on board the boat, fall to singing, each taking a different part, and carrying it on with great spirit and independence, and in perfect harmony, as I never heard singers, who had not been considerably educated, at the North.

Touching the intellectual capacity of negroes: I was dining with a gentleman, when he asked the waiter—a lad of eighteen—to tell him what the time was. The boy, after studying the clock, replied incorrectly; and the gentleman said it was impossible for him to make the simple calculation necessary. He had promised to give him a dollar, a year ago, whenever he could tell the time by the clock; had taken a good deal of trouble to teach him, but he did not seem to make any progress. I have since met with another negro boy, having the same remarkable inability—both the lads being intelligent, and learning easily in other respects: the first could read. I doubt if it is a general deficiency of the race; both these boys had marked depressions where phrenologists locate the organ of calculation.

A gentleman, whom I visited, in Montgomery, had a carpenter, who was remarkable for his mathematical capacities. Without having had any instruction, he was able to give very close and accurate estimates for the quantity of all descriptions of lumber, to be used in building a large and handsome dwelling, of the time to be employed upon it, and of its cost. He was an excellent workman; and, when not occupied with work directly for his master, obtained employment of others—making engagements, and taking contracts for jobs, without being required to consult his master. He had been purchased for two thousand dollars, and his ordinary wages were two dollars a day. He earned considerable money besides, for himself, by overwork at his trade, and still more in another way.

He was a good violinist and dancer, and, two nights a week, taught a negro dancing-school, from which he received two dollars a night, which, of course, he spent for his own pleasure. During the winter, the negroes, in Montgomery, have their “assemblies,” or dress balls, which are got up “regardless of expense,” in very grand style. Tickets are advertised to these balls, “admitting one gentleman and two ladies, $1;” and “Ladies are assured that they may rely on the strictest order and propriety being observed.” Cards of invitation, finely engraved with handsome vignettes, are sent, not only to the fashionable slaves, but to some of the more esteemed white people, who, however, take no part, except as lookers-on. All the fashionable dances are executed; no one is admitted, except in full dress: there are the regular masters of ceremonies, floor committees, etc.; and a grand supper always forms a part of the entertainment.

While in a book-store, in Montgomery, I saw a negro looking at some very showy London valentines. After examining the embossed envelopes, and the colored engravings of hearts and darts, and cupids and doves, he would ask the clerk to read the poetry, and listen while he did so, with the air of a profound critic. I heard ten dollars mentioned as the price of one of them; and I presume he was ready to pay that price, if he could find an adequate expression of his sentiment.

My friend had so much confidence in the discretion and faithfulness of his carpenter, that he seldom gave him any orders or directions. To enable him to execute some business with greater celerity, he, one day, in my observation, took a horse that his master was intending to use himself. When asked why he did so, he mentioned the object he had in view, and said: “I thought I needed him more than you did”—and was not reproved.

On visiting a piece of ground that his master owned, out of town, we found him engaged, with two black men and one white—a native, country fellow—in putting up a fence. The latter was acting under his orders; and, upon inquiry, I found that, seeing that the work was needed to be done immediately, he had hired him, as well as the two blacks, without consulting his master. It was the first case I had seen of a white man acting under the orders of a negro, though I have several times since seen Irishmen doing so.

This gay carpenter’s wife was a woman of serious sentiments, and preferred prayer-meetings to balls; so they did not agree very well. She belonged to another gentleman, who did not live in the town, and was at service in another family than that with which her husband was connected. She had informed her owner that, if he would like to take her into the country with him, she had no particular objections to being separated from her husband. She did not like him very much—he was “so gay.”

It is frequently remarked by Southerners, in palliation of the cruelty of separating relatives, that the affections of negroes for one another are very slight. I have been told by more than one lady that she was sure her nurse did not have half the affection for her own children that she did for her mistress’s. But it is evident that this loyalty is not peculiar to the black race. Probably there are many white people in Europe, even in this day, who would let their children’s lives be sacrificed to save the life of the son of their sovereign. They teach this as a duty, and use the Bible to make it appear so, in Prussia, if not in England.

A very excellent lady, to show me how little cruelty there was in the separation of husband and wife, told me that when she lived at home, on her father’s plantation, in South Carolina, he had given her a girl for a dressing-maid. This girl, after a time, married a man on the plantation. The marriage ceremony was performed by an Episcopal clergyman, according to the prayer-book form—the parties, of course, promising to cleave together until death should part them. A year later, the lady herself was to be married, and was to remove with her husband to his residence in Alabama. She told the girl she could do as she pleased—go with her and leave her husband, or remain with her husband and be separated from her. She preferred to cleave to her mistress. She accordingly parted from her husband, with some expressions of regret for the necessity, but with no appearance of grief or sadness. Neither did the husband complain. A month after she reached her new residence in Alabama, she found a new husband; and it was supposed that her former husband had suited himself with a new woman. She had now been living ten years in Alabama, and had several children; she was expecting soon to be taken with her mistress on a visit to the old plantation in South Carolina, and laughed as she spoke of probably meeting her old husband again.

A slave, who was hired (not owned) by a friend of mine in Savannah, called upon him one morning while I was there, to say that he wished to marry a woman in the evening, and wanted a ticket from him to authorize the ceremony.

“I thought you were married,” said my friend.

“Yes, master, but that woman hab leave me, and go ’long wid ’nodder man.”

“Indeed! Why, you had several children by her, did not you?”

“Yes, master, we hab thirteen, but now she gone ’long wid ’nodder man.”

“But will your church permit you to marry another woman so soon?”

“Yes, master; I tell ’em de woman I had leave me, and go ’long wid ’nodder man, and she say she don’t mean to come back, and I can’t be ’spected to lib widout any woman at all, so dey say dey grant me de divorce.”

A pleasant example of the child-like confidence which a slave frequently has in his sovereign, when he is a good-hearted and trustworthy man, occurred to me at a hotel, where I had been waited upon for several days by an unusually good servant. One morning, while making a fire for me, he said—

“Dey say Congress is going to be bruck up in tree week— I’se glad enough o’ dat.”

“Glad of it—why so?”

“I’se got a master dah; I’ll be a heap glad when he’s come back.”

“You want to see him again, eh?”

“Yes, sar. I won’t stay long in dis place wen he com, nudder. I’ll hab im get noder place for me. I don’ like dis place, no how; dis place don’ suit me; never saw sich a place. Dey keeps me up most all night; I haan been used to sich treatem. Dey haan got but one servant for all dis hall; dey ought to hab two at de least. I’m de olest servant in de house; all de odder ole servant is gone.”

“And they have got Irishmen in their places.”

“Yes! and what kine of servant is dey? Ha! all de Irish men dat ever I see haden so much sense in dar heds as I could carry in de palm of my han. I was de head waiter allers in my master’s house till my brudder grew up, and I learned him; he’s de head waiter now. And dis heah ant no kine of place for my sort; I don’ stay here no longer wen my master come back.”

A few mornings after this, he did not come into my room, as usual; I was out during the forenoon; when I returned, he came to me, and said:

“You must excuse me dat I din’t be heah to brush your clothes dis mornin’, sar; dey had me in de guard-house, last night.”

“Had you in the guard-house—what for?”

“Because I was out widout a pass. You see I don’ sleep heah, sar, and I was jes gwine down to de boat, ’bout two o’clock, and dey took me, and put me in de guard-house.”

“And what kind of accommodations do they give you at the guard-house?”

“Why, dey makes me pay a dollar for ’em. I offered dem two dollars las’ night, if dey let me go. I tort dat’s de way dey do; make you pay two dollar, or else dey gives you a right smart whippin’; but dey didn’—I don’ know why. I tell you, sar, I nebber felt so mortify in all my life, as wen dey lets me out de guard-house dis mornin’, right before all de people in dat ar market-place.”

“Well, I suppose it was your own fault.”

“No, sar! not my own fault ’tall, sar; dey ought to gib me a pass; why not? dey knows I’s a married man. Do dey tink I’s gwine to sleep heah wid dese nasty niggers? No, sar! I lie out dah on de floor in de passage, and catch my deff of cold first. I aint been use to sich treatem. I’s got a master. My master’s member Congress. Wen dat broks up, he mus fine me nodder place mighty quick. I don’ stay heah. I’s always been a family servant. You see, sar, I aint use to such treatem. Nebber was sole yet in all my life. My missis’ fader was worf four hundred tousand dollar, and we had two plantation. Nebber was in a field in my life—allers was in de house ebber since I was a little chile. I was a kine of pet boy, you see, master. I allers wait on my masser myself till my little brudder got big enough; den I want to go ’way. Oh, I’se a wild chile, you see, sar, and I want to clear out and hab some fun to myself. I’s a kine of favorite allers to my mistress. She ’ould do anything for me. She wanted to learn me to read, but I’ru too wild. She would gib me a first-rate education, I ’spose, only I’s so wild I wouldn’.”

“Can’t you read at all!”

“Well, I ken read some, but not very well. Dat is, you see, master, dere’s some of de letters I can’t read, not all on ’em I can’t; no sar; but I ken read some.”

There were about one hundred passengers on the Fashion, besides a number of poor people and negroes on the lower deck. They were, generally, cotton-planters, going to Mobile on business, or emigrants bound to Texas or Arkansas. They were usually well dressed, but were a rough, coarse style of people, drinking a great deal, and most of the time under a little alcoholic excitement. Not sociable, except when the topics of cotton, land, and negroes, were started; interested, however, in talk about theatres and the turf; very profane; often showing the handles of concealed weapons about their persons, but not quarrelsome, avoiding disputes and altercations, and respectful to one another in forms of words; very ill-informed, except on plantation business; their language very ungrammatical, idiomatic, and extravagant. Their grand characteristics—simplicity of motive, vague, shallow, and purely objective habits of thought; spontaneity and truthfulness of utterance, and bold, self-reliant movement.

With all their individual independence, I soon could perceive a very great homogeneousness of character, by which they were distinguishable from any other people with whom I had before been thrown in contact; and I began to study it with interest, as the Anglo-Saxon development of the Southwest.

I found that, more than any people I had ever seen, they were unrateable by dress, taste, forms, and expenditures. I was perplexed by finding, apparently united in the same individual, the self-possession and confidence of the well equipped gentleman, and the coarseness and low tastes of the uncivilized boor—frankness and reserve, recklessness and self restraint, extravagance, and penuriousness.

There was one man, who “lived, when he was to home,” as he told me, “in the Red River Country,” in the northeastern part of Texas, having emigrated thither from Alabama, some years before. He was a tall, thin, awkward person, and wore a suit of clothes (probably bought “ready-made”) which would have better suited a short, fat figure. Under his waistcoat he carried a large knife, with the hilt generally protruding at the breast. He had been with his family to his former home, to do a little business, and visit his relatives, and was now returning to his plantation. His wife was a pale and harassed looking woman; and he scarce ever paid her the smallest attention, not even sitting near her at the public table. Of his children, however, he seemed very fond; and they had a negro servant in attendance upon them, whom he was constantly scolding and threatening. Having been from home for six weeks, his impatience to return was very great, and was constantly aggravated by the frequent and long continued stoppages of the boat. “Time’s money, time’s money!” he would be constantly saying, while we were taking on cotton, “time’s worth more ’n money to me now; a hundred per cent more, ’cause I left my niggers all alone, not a dam white man within four mile on ’em.”

I asked how many negroes he had.

“I’ve got twenty on ’em to home, and thar they ar! and thar they ar! and thar aint a dam soul of a white fellow within four mile on’’em.”

“They are picking cotton, I suppose?”

“No, I got through pickin’ fore I left.”

“What work have they to do, then, now?”

“I set em to clairin’, but they aint doin’ a dam thing—not a dam thing, they aint; that’s wat they are doin’, that is—not a dam thing. I know that, as well as you do. That’s the reason time’s an object. I told the capting so wen I came a board: ‘ says I, capting, says I, time is in the objective case with me.’ No, sir, they aint doin’ a dam solitary thing; that’s what they are up to. I know that as well as anybody; I do. But I’ll make it up, I’ll make it up, when I get thar, now you’d better believe.”

Once, when a lot of cotton, baled with unusual neatness, was coming on board, and some doubt had been expressed as to the economy of the method of baling, he said very loudly:

“Well, now, I’d be willin’ to bet my salvation, that them thar’s the heaviest bales that’s come on to this boat.”

“I’ll bet you a hundred dollars of it,” answered one.

“Well, if I was in the habit of bettin’, I’d do it. I aint a bettin’ man. But I am a cotton man, I am, and I don’t car who knows it. I know cotton, I do. I’m dam if I know anythin’ but cotton. I ought to know cotton, I had. I’ve been at it ever sin’ I was a chile.”

“Stranger,” he asked me once, “did you ever come up on the Leweezay? She’s a right smart, pretty boat, she is, the Leweezay; the best I ever see on the Alabamy river. They wanted me to wait and come down on her, but I told ’em time was in the objective case to me. She is a right pretty boat, and her capting’s a high-tone gentleman; haint no objections to find with him—he’s a high-tone gentleman, that’s what he is. But the pilot—well, damn him! He run her right out of the river, up into the woods—didn’t run her in the river, at all. When I go aboard a steam-boat, I like to keep in the river, somewar; but that pilot, he took her right up into the woods. It was just clairin’ land. Clairin’ land, and playin’ hell ginerally, all night; not follering the river at all. I believe he was drunk. He must have been drunk, for I could keep a boat in the river myself. I’ll never go in a boat where the pilot’s drunk all the time. I take a glass too much myself, sometimes; but I don’t hold two hundred lives in the holler of my hand. I was in my berth, and he run her straight out of the river, slap up into the furest. It threw me clean out of my berth, out onter the floor; I didn’t sleep any more while I was aboard. The Leweezay’s a right smart, pretty little boat, and her capting’s a high-tone gentleman. They hev good livin’ aboard of her, too. Haan’t no objections on that score; weddin’ fixins all the time; but I won’t go in a boat war the pilot’s drunk. I set some vally on the life of two hundred souls. They wanted to hev me come down on her, but I told ’em time was in the objective case.”

There were three young negroes, carried by another Texan, on the deck, outside the cabin. I don’t know why they were not allowed to be with the other emigrant slaves, on the lower deck, unless the owner was afraid of their trying to get away, and had no handcuffs small enough for them. They were boys; the oldest twelve or fourteen years old, the youngest not more than seven. They had evidently been bought lately by their present owner, and probably had just been taken from their parents. They lay on the deck and slept, with no bed but the passengers’ luggage, and no cover but a single blanket for each. Early one morning, after a very stormy night, when they must have suffered much from the driving rain and cold, I saw their owner with a glass of spirits, giving each a few swallows from it. The older ones smacked their lips, and said, “Tank ’on, massa;” but the little one couldn’t drink it, and cried aloud, when he was forced to. The older ones were very playful and quarrelsome, and continually teasing the younger, who seemed very sad, or homesick and sulky. He would get very angry at their mischievous fun, and sometimes strike them. He would then be driven into a corner, where he would lie on his back, and kick at them in a perfect frenzy of anger and grief. The two boys would continue to laugh at him, and frequently the passengers would stand about, and be amused by it. Once, when they had plagued him in this way for some time, he jumped up on to the cotton-bales, and made as if he would have plunged overboard. One of the older boys caught him by the ankle, and held him till his master came and hauled him in, and gave him a severe flogging with a rope’s end. A number of passengers collected about them, and I heard several say, “That’s what he wants.” Red River said to me, “I’ve been a watchin’ that ar boy, and I see what’s the matter with him; he’s got the devil in him right bad and he’ll hev to take a right many of them warmins before it’ll be got out.”

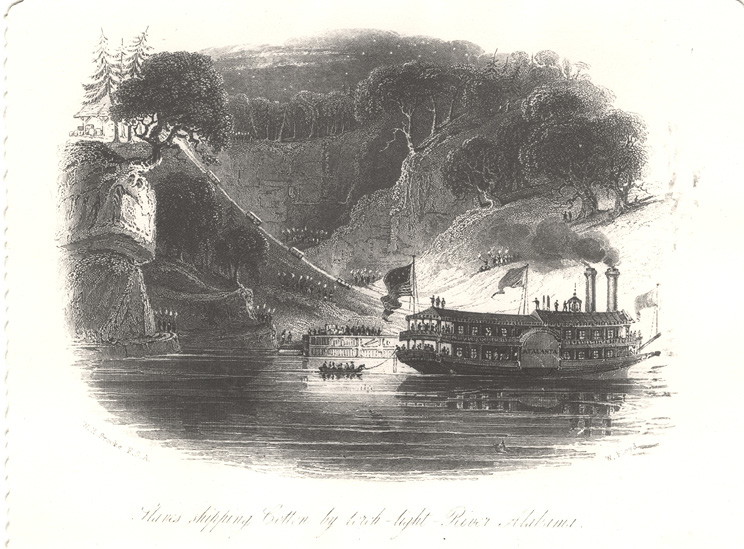

Engraving of “Slaves Shipping Cotton by Torch Light—River Alabama.”

The crew of the boat, as I have intimated, was composed partly of Irishmen, and partly of negroes; the latter were slaves, and were hired of their owners at $40 a month—the same wages paid to the Irishmen. A dollar of their wages was given to the negroes themselves, for each Sunday they were on the passage. So far as convenient, they were kept at work separately from the white hands; they were also messed separately. On Sunday I observed them dining in a group, on the cotton-bales. The food, which was given to them in tubs, from the kitchen, was various and abundant, consisting of bean-porridge, bacon, corn bread, ship’s biscuit, potatoes, duff (pudding), and gravy. There was one knife used only, among ten of them; the bacon was cut and torn into shares; splinters of the bone and of fire-wood were used for forks; the porridge was passed from one to another, and drank out of the tub; but though excessively dirty and beast-like in their appearance and manners, they were good-natured and jocose as usual.

“Heah! you Bill,’’ said one to another, who was on a higher tier of cotton, “pass down do dessart. You! up dar on de hill; de dessart! Augh! don’t you know what de dessart be? De duff, you fool.”

“Does any of de gemmen want some o’ dese potatum?” asked another; and no answer being given, he turned the tub full of potatoes overboard, without any hesitation. It was evident he had never had to think on one day how he should be able to live the next.

Whenever we landed at night or on Sunday, for wood or cotton, there would be many negroes come on board from the neighboring plantations, to sell eggs to the steward.

Sunday was observed by the discontinuance of public gambling in the cabin, and in no other way. At midnight gambling was resumed, and during the whole passage was never at any other time discontinued, night or day, so far as I saw. There were three men that seemed to be professional sharpers, and who probably played into each other’s hands. One young man lost all the money he had with him—several hundred dollars.

MOBILE.

. . . .

CHAPTER X

ECONOMICAL EXPERIENCE.

The territorial Government of Alabama was established in 1816 [1817], and in 1818 [1819] she was admitted as a State into the Union. In 1820, her population was 128,000; in 1850, it had increased to 772,000; the increase of the previous ten years having been 30 per cent. (that of South Carolina was 5 per cent.; of Georgia, 31; Mississippi, 60; Michigan, 87; Wisconsin, 890). A large part of Alabama has yet a strikingly frontier character. Even from the State-house, in the fine and promising town of Montgomery, the eye falls in every direction upon a dense forest, boundless as the sea, and producing in the mind the same solemn sensation. Towns frequently referred to as important points in the stages of your journey, when you reach them, you are surprised to find consist of not more than three or four cabins, a tavern or grocery, a blacksmith’s shop, and a stable.

A stranger once meeting a coach, in which I was riding, asked the driver whether it would be prudent for him to pass through one of these places, that we had just come from; he had heard that there were more than fifty cases of small-pox in the town. “There ain’t fifty people in the town, nor within ten mile on’t,” answered the driver, who was a northerner. The best of the country roads are but little better than open passages for strong vehicles through the woods, made by cutting away the trees.

The greater number of planters own from ten to twenty slaves only, though plantations on which from fifty to a hundred are employed are not uncommon, especially on the rich alluvial soils of the southern part of the State. Many of the largest and most productive plantations are extremely unhealthy in summer, and their owners seldom reside upon them, except temporarily. Several of the larger towns, like Montgomery, remarkable in the midst of the wilderness which surrounds them, for the neatness and tasteful character of the houses and gardens which they contain, are in a considerable degree, made up of the residences of gentlemen who own large plantations in the hotter and less healthful parts of the State. Many of these have been educated in the older States, and with minds enlarged and liberalized by travel, they form, with their families, cultivated and attractive society.

Much the larger proportion of the planters of the State live in log-houses, some of them very neat and comfortable, but frequently rude in construction, not chinked, with windows unglazed, and wanting in many of the commonest conveniences possessed by the poorest class of Northern farmers and laborers of the older States. Many of those who live in this way, possess considerable numbers of slaves, and are every year buying more. Their early frontier life seems to have destroyed all capacity to enjoy many of the usual luxuries of civilized life.

“A Southern Planter’s Home in Alabama.”

Notwithstanding the youth of the State, there is a constant and extensive emigration from it, as well as immigration to it. Large planters, as their stock increases, are always anxious to enlarge the area of their land, and will often pay a high price for that of any poor neighbor, who, embarrassed by debt, can be tempted to move on. There is a rapid tendency in Alabama, as in the older Slave States, to the enlargement of plantations. The poorer class are steadily driven to occupy poor land, or move forward on to the frontier.

In an Address before the Chunnennggee Horticultural Society, by Hon. C. C. Clay, Jr., reported by the author in De Bow’s Review, December, 1855, I find the following passage. I need add not a word to it to show how the political experiment of old Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia, is being repeated to the same cursed result in young Alabama. The author, it is fair to say, is devoted to the sustentation of Slavery, and would not, for the world, be suspected of favoring any scheme for arresting this havoc of wealth, further than by chemical science:

“I can show you, with sorrow, in the older portions of Alabama, and in my native county of Madison, the sad memorials of the artless and exhausting culture of cotton. Our small planters, after taking the cream off their lands, unable to restore them by rest, manures, or otherwise, are going further west and south, in search of other virgin lands, which they may and will despoil and impoverish in like manner. Our wealthier planters, with greater means and no more skill, are buying out their poorer neighbors, extending their plantations, and adding to their slave force. The wealthy few, who are able to live on smaller profits, and to give their blasted fields some rest, are thus pushing off the many, who are merely independent.

“Of the twenty millions of dollars annually realized from the sales of the cotton crop of Alabama, nearly all not expended in supporting the producers is reinvested in land and negroes. Thus the white population has decreased, and the slave increased, almost pari passu in several counties of our State. ln 1825, Madison county cast about 3,000 votes; now she cannot cast exceeding 2,300. In traversing that county one will discover numerous farm-houses, once the abode of industrious and intelligent freemen, now occupied by slaves, or tenantless, deserted, and dilapidated; he will observe fields, once fertile, now unfenced, abandoned, and covered with those evil harbingers—fox-tail and broom-sedge; he will see the moss growing on the mouldering walls of once thrifty villages; and will find ‘one only master grasps the whole domain’ that once furnished happy homes for a dozen white families. Indeed, a country in its infancy, where, fifty years ago, scarce a forest tree had been felled by the axe of the pioneer, is already exhibiting the painful signs of senility and decay, apparent in Virginia and the Carolinas; the freshness of its agricultural glory in gone; the vigor of its youth is extinct, and the spirit of desolation seems brooding over it.”