1

Constructing The Chaplin Machine:

The Constructivist International Encounters the American Comedians

If one considers the dangerous tensions which technology and its consequences have engendered in the masses at large – tendencies which at critical stages take on a psychotic character – one also has to recognise that the same technologisation has created the possibility of psychic immunisation against such psychoses. It does so by means of certain films in which the forced development of sadistic fantasies or masochistic delusions can prevent their natural and dangerous maturation in the masses. Collective laughter is one such pre-emptive and healing outbreak of mass psychosis. The countless grotesque events consumed in films are a graphic indication of the dangers threatening mankind from the repressions implicit in civilisation. American slapstick comedies and Disney films trigger a therapeutic release of unconscious energies. Their forerunner was the figure of the eccentric. He was the first to inhabit the new fields of action opened up by film – the first occupant of the newly built house. This is the context in which Chaplin takes on historical significance.

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility’, 19361

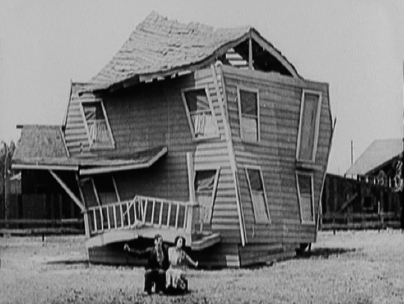

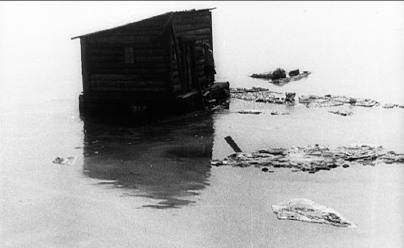

For Walter Benjamin, the new landscape of the ‘Second Industrial Revolution’, with its mass production factories, new means of transport and communication, and its increased geographical spread and its concentration of population and labour, is incarnated as a ‘newly built house’ – but a newly built house which, we can expect, resembles the theatrical constructions of Vesnin and Popova, or, as we shall soon see, of Buster Keaton – a house full of trapdoors, mass-produced, jerry-built or prefabricated, but with a new spatial potential, where its multiple pitfalls can be faced without incurring real pain, real physical damage – traversed, if not transcended. The person that can live in it is the Soviet figure of the Eccentric, who has adapted himself to the precipitous new landscape, and has learned to laugh at it; in turn the audience, who may well live in these new houses too, learn to live in them in turn. To get some notion of what the newly built house is like, we could turn to the one in Buster Keaton’s One Week (1920): a prefabricated house whose pieces are assembled in the wrong order, which is alternately dragged along a road and knocked down by a train, but which in between provides a series of vivid and joyous surprises for its inhabitants and the audience. Alternatively, it could be like the house in Lev Kuleshov’s Americanist gold-rush melodrama By The Law (1926), another minimal, wooden construction placed in the barren Western expanse, which begins as a sweet petit-bourgeois homestead but soon becomes consecutively an execution chamber and a flooded, marooned wreck, left desolate and hopelessly bleak.

Comic Anti-Humanism

According to Benjamin, the Eccentric is Chaplin. But what sort of a man can live in this new house? Is Chaplin a man at all? In Movies for the Millions, a 1937 study of the popular consumption of cinema, the critic Gilbert Seldes made the observation, in the context of a discussion of the comic film, that there was something uncanny about Charles Chaplin. Several pages after an encomium to Chaplin’s genius (as ‘the universal man of our time’) he remarks, almost as an aside, ‘(W.C.) Fields is human. Chaplin is not’. Chaplin’s inhumanity is then defined as a consequence of this universalism, combined with a resemblance to a doll, an automaton.

Buster Keaton’s newly built house

A house stranded, in Lev Kuleshov’s By The Law

He is not [human] because perfection is not human and Chaplin achieves perfection. A French critic has said that in his early works Chaplin presented a marionette and in his later masterpieces endowed that marionette with a soul. That is one way of putting it. It is also true that he created a figure of folklore – and such figures, while they sum up many human attributes, are far beyond humanity themselves.2

This provides an interesting contrast with the more familiar idea of Chaplin as a mawkish sentimentalist. ‘Chaplin’ is not a human being, and is not a realistically depicted subject – he is both machine and archetype. In this he serves as an obvious paradigm for the avant-garde. In his earlier films (principally those made for the Essanay, Mutual and First National studios in the late 1910s, before the character of the ‘little Tramp’ was finalised, humanised) ‘Chaplin’ is involved, largely, in everyday situations, albeit in dramatic versions. He is a cleaner in a bank, he is a stroller in a park, he is a petty criminal, he is pawning all his possessions. This universal everyday is made strange, through use of the accoutrements of the everyday for purposes other than those intended, and through the peculiarly anti-naturalistic movements of Chaplin’s own body. Chaplin wrote the preface to Movies for the Millions (where he uses the opportunity to denounce the Hays code), so we can assume he had no particular problem with being branded inhuman (or sur-human). Yet however odd they seem in this relatively mainstream study, Seldes’ observations were not new. Here we will turn to the avant-garde takes on Chaplin. The field is huge, ranging from El Lissitzky and Ilya Ehrenburg’s Veshch-Gegenstand-Objet to Iwan Goll, from Erwin Blumenfeld to Fernand Léger; but here we will concentrate on the accounts of Viktor Shklovsky, Oskar Schlemmer, the Soviet magazine Kino-Fot and Karel Teige.

The reception of Chaplin by the Soviet and Weimar avant-garde from the early 1920s onwards3 hinges precisely on a dialectic of the universal and the machinic. Viktor Shklovsky edited a collection of essays on Chaplin in Berlin in 1922, and in Literature and Cinematography, published in the USSR the following year, he devotes a chapter to Chaplin; in fact, he is the only ‘cinematographer’ mentioned by name in this dual study of literature and film. Shklovsky describes this early use of multiple identities as ‘a manifestation of the need to create disparities, which compels a fiction writer to turn one of his images into a permanent paragon (a yardstick of comparison) for the entire work of art.’4 In this sense, then, Chaplin’s universalism would seem to be a means of enabling the other characters, or the events in the film, to take place, giving them centre stage. This doesn’t at all tally with the idea of Chaplin as unique ‘star’, and clearly suggests Shklovsky was only familiar with the short films preceding the feature The Kid (1921), where the tramp character emerged fully developed. The remarks that follow, however, are more insightful:

Chaplin is undoubtedly the most cinematic actor of all. His scripts are not written: they are created during the shooting [. . .] Chaplin’s gestures and films are conceived not in the word, nor in the drawing, but in the flicker of the gray-and-black shadow [. . .] he works with the cinematic material instead of translating himself from theatrical to film language.5

Chaplin is immanent to cinema, and this is what makes him interesting for Shklovsky’s purposes: formulating a theory unique to film as an art form, disdaining the ‘psychological, high society film’6 which merely imposes theatre upon a new, radically different art. Chaplin moves in a new way, through a new space.

Shklovsky’s short discussion of Chaplin includes two observations which, as we will see, are common in the avant-garde’s reception of his work, which are to do with how the body of the Chaplin-machine moves through cinematic space. First, again, we have Chaplin as machine, something about which Shklovsky is initially rather tentative: ‘I cannot define right now what makes Chaplin’s movement comical – perhaps the fact that it is mechanised.’ Similarly, this movement – mechanised or not – is something which immediately sets him apart from the other protagonists in the films, which marks him out from the ordinary run of humanity. ‘Chaplin’s ensemble moves differently than its leader.’ Shklovsky claims also that Chaplin is an artist who bares his devices, something that would be picked up over a decade later in Brecht’s ‘V-Effects of Chaplin’.7 More specifically, a baring of the ‘purely cinematic essence of all the constituents in his films’ occurs. This is done partly through the avoidance of intertitles (and, he notes, one never sees Chaplin move his lips to simulate speech), and partly through a series of devices physical or technical: ‘falling down a manhole, knocking down objects, being kicked in the rear’. So, in Shklovsky’s brief, early discussion of Chaplin we find three principal elements which are usually ascribed to the products of the avant-garde: a sort of impersonal universalism, a human being who isn’t a ‘subject’, and an alien element thrown into the everyday; a mechanisation of movement; and the baring of technical devices.

An instructive example of this correspondence being put to use, although not a cinematic one, can be found in the Bauhaus master Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, which shows the influence of these three elements: figures which, as in the Commedia dell’arte, are (to put it in Eisenstein’s terms) ‘types’, not subjects; a focus on mechanisation (here taken much further, with the costumes seemingly borrowing from the forms of ball-bearings, lathes, spinning tops and other toys); and an acting style which makes the construction of gesture obvious, rather than concealed. It is unsurprising, then, that Schlemmer can be found making similar remarks about Chaplin. In a Diary entry of September 1922, written while formulating the Triadic Ballet, he writes of a preference for ‘aesthetic mummery’ as opposed to the ‘cultic soul dance’ of communitarian, ritualistic forms of dance. Schlemmer argues for an aesthetic of artifice and mechanised movement:

The theatre, the world of appearances, is digging its own grave when it tries for verisimilitude: the same applies to the mime, who forgets that his chief characteristic is his artificiality. The medium of every art is artificial, and every art gains from recognition and acceptance of its medium. Heinrich Kleist’s essay Uber das Marionettentheater offers a convincing reminder of this artificiality, as do ETA Hoffmann’s Fantasiestücke (the perfect machinist, the automata). Chaplin performs wonders when he equates complete inhumanity with artistic perfection.8

The automaton, the machine, artifice: Chaplin is seen as a culmination of a Romantic tendency to create strange, uncanny, inhuman machines that resemble human beings. Mechanisation is accordingly seen as something linked as much with dance and comedy as with factory work – or more specifically, dance and comedy provide a means of coming to terms with the effects of factory work and the attendant proliferation of machines. Schlemmer continues: ‘life has become so mechanised, thanks to machines and a technology which our senses cannot possibly ignore, that we are intensely aware of man as a machine and the body as a mechanism.’ Schlemmer claims that this then leads to two only seemingly competing impulses: a search for the ‘original, primordial impulses’ that apparently lie behind artistic creativity on the one hand, and an accentuation of ‘man as a machine’ on the other. By merging the ‘Dionysian’ dance with ‘Apollonian’ geometries, Schlemmer claims the Triadic Ballet will provide some sort of yearned-for synthesis between the two. Although he does not acknowledge this, it is possible that Chaplin’s combination of mechanisation and sentiment provides a similar synthesis. Chaplin is the machine that cries.

This has a great deal in common with Walter Benjamin’s anatomy of the ‘Chaplin-machine’ in his notes for a review of The Circus (1928), where Chaplin is both an implement and a marionette, noting both that he ‘greets people by taking off his bowler, and it looks like the lid rising from the kettle when the lid boils over’; and that ‘the mask of non-involvement turns him into a fairground marionette’.9 Benjamin implies something deeper here, that this is a ‘mask’ of sanguine inhumanity, under which something more poignant and sophisticated is at work. Another of Benjamin’s observations merges Shklovsky’s positing of something immanently cinematic about Chaplin with the notion that his movement is machinic – in fact, his motion is that of the cinema itself. In a 1935 fragment he notes that the film is based on a succession of discontinuous images, in which the assembly line itself is represented. Chaplin incarnates this process.

He dissects the expressive movements of human beings into a series of minute innervations. Each single movement he makes is composed of a series of staccato bits of movement. Whether it is his walk, the way he handles his cane, or the way he raises his hat – always the same jerky sequence of tiny movements applies the law of the cinematic image sequence to human motorial functions. Now, what is it about such behaviour that is distinctively comic?10

Shklovsky suggests tentatively that it is this machinic movement itself which is comic, that Chaplin is funny precisely because he is mechanised, in which perhaps the audience detects the process at work in the film in the actions onscreen, or perhaps recognise their own increasing integration in the factories where most of them work into an ever-more mechanised capitalism, and are made to laugh at it to dispel resentment and tension. The tension, trite as it may sound, appears to be between machinic movement and personal pathos – but in the process the pathos itself may become machinic.

Meanwhile, Schlemmer’s brand of Romantic-inflected artistic syntheses is entirely absent in another avant-garde celebration of Chaplin: a 1922 cover story for the Constructivist film journal Kino-Fot, edited by Alexei Gan, a publication described at the time by hostile critics as ‘cheap, American-like’.11 This is a collaboration between Aleksandr Rodchenko (as writer, of a strange prose-poem eulogising the actor-director) and Varvara Stepanova (as illustrator, providing woodcuts interspersed with the text) titled ‘Charlot’, the name of Chaplin’s ‘character’ in France. Here, again, there is a stress on the ordinary and everyday, and Chaplin’s universalisation thereof, as well as on technology. However, there is an acknowledgement of the ‘affecting’ nature of the performance, something ascribed to the humility of the Chaplin character, and a certain ingenuousness.

He pretends to be no one,

Never worries at all,

Rarely changes his costume,

wears no make-up,

remains true to himself, never mocks a soul.

He simply knows how to reveal himself so fully and audaciously that he affects the viewer more than others do.12

Aside from the bizarre failure of Rodchenko to notice the layers of kohl and foundation applied for even the more naturalistic Chaplin performances, this is curious as it suggests that precisely in his otherness, his strangeness in his context (‘his movement contrasts with the movement of his partner’, something also noted by Shklovsky), Chaplin becomes more emotionally involving for the viewer. This ‘revealing himself’ however is not a dropping of the mask for the purpose of pathos – indeed, Rodchenko claims that ‘he has no pathos’. There is a certain smallness to Chaplin in Rodchenko’s text. While he avoids the accoutrements of the ‘psychological, high-society film’, what Rodchenko calls ‘the old tinsel of the stage’, Chaplin also effaces the machine monumentalism of the period (‘dynamo, aero, radio station, cranes and so on’). The machine is transferred to a human scale, as ‘next to a mountain or a dirigible a human being is nothing, but next to a screw and one surface – he is Master.’ Machine life is on a human scale here: it is everyday, not grandiose. Chaplin then, is something ordinary and alien. The text’s conclusion is that ‘simply nothing – the ordinary – is higher than the pompousness and muddlehead-edness of speculative ideologies. Charlot is always himself – the one and only, the ordinary Charlie Chaplin.’

Chaplin as everyman and as ‘master’ is conflated, an unstable and unresolved contradiction. Yet what marks out Rodchenko’s Chaplin-machine from Shklovsky or Schlemmer’s marionette is a political dimension, something too often overlooked in even the earliest of his films. Nonetheless, Chaplin here takes the place more commonly assigned to Ford or Taylor in terms of providing a bridge between Bolshevism and Americanism.

(Chaplin’s) colossal rise is precisely and clearly – the result of a keen sense of the present day: of war, revolution, Communism.

Every master-inventor is inspired to invent by new events or demands.

Who is it today?

Lenin and technology.

The one and the other are the foundation of his work.

This is the new man designed – a master of details, that is, the future anyman [. . .]

The masters of the masses –

Are Lenin and Edison.13

This elliptical text offers few clues as to why exactly Communism should be one of the foundations of Chaplin’s rise – although we will suggest a few possibilities presently – but another element has been added to those of the avant-garde Chaplin. He is a new man, and a potentially Socialist one. Stepanova’s illustrations, however, have little to do with this extra element. Here, we have a depiction of the Chaplin-machine as montage, in a more casual, rough, representational version of Suprematist abstraction, but sharing the alignment of discrete shapes. He is made up of clashing, patterned rectangles and a circle for a head, poised as if about to leap. The only elements about him that aren’t drawn from the Suprematist vocabulary are the fetish objects mentioned in Rodchenko’s text: the bowler hat, the cane and the arse. Her illustration for the cover of the issue of Kino-Fot, meanwhile, features the famous moustache, in a dynamic, symmetrical composition in which Chaplin swings from his cane towards the spectator, flat feet first. The monochrome palette of the magazine cover is exploited to give Chaplin’s legs a sharp stylisation, his pinstripes futuristically thrusting forwards. Stepanova’s Chaplin-machine is fiercer than Rodchenko’s, it seems. Still a ‘new man’, he displays fewer traces of the human scale.

There is a question, however, of whether or not there is a Chaplinism of practice, rather than of spectatorship. Can Charlot alone be the universal man-machine, or can the audience that he is habituating to the ‘newly built house’ themselves live in this manner? Is Chaplin the only alien element in the everyday, or could the everyday itself be transformed? A possible answer to this could be found with the avant-garde group Devetsil in Czechoslovakia, a country whose tensions between Americanised rationalised industry and an active labour movement and Communist Party were similar to those of Weimar Germany. Devetsil’s goal was ‘Poetism’, as defined in Karel Teige’s 1924 Manifesto. Teige defines this as a kind of complement to Constructivism in the plastic arts (‘poetism is the crown of life; constructivism is its basis [. . .] not only the opposite but the necessary complement of constructivism [. . .] based on its layout’14), as a kind of practice of life-as-play, rejecting the ‘professionalism of art’, ‘aesthetic speculation’, ‘cathedrals and galleries’ and the other institutions ritually lambasted in the avant-garde manifesto. Poetism is ‘not a worldview – for us, this is Marxism – but an ambiance of life [. . .] it speaks only to those who belong to the new world.’ It combines the Constructivism derived no doubt from ‘Lenin and Edison’ with what an ‘aesthetic skepticism’ learned from ‘clowns and Dadaists’. Those clowns are listed, in what marks an interesting contention given the prevalent received idea of ‘high’ Modernism, or an aloof, puritan avant-garde:

it is axiomatic that man has invented art, like everything else, for his own pleasure, entertainment and happiness. A work of art that fails to make us happy and to entertain is dead, even if its author were to be Homer himself. Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Burian, a director of fireworks, a champion boxer, an inventive or skilful cook, a record breaking mountain climber – are they not even greater poets?

Poetism is, above all, a way of life.15

In the Poetist conception, the avant-garde’s place for Chaplinism is in life. Americanism in technology, Bolshevism in politics, slapstick in everyday life. This puts a rather different spin on the idea of the utopian ‘new man’ of the 1920s – not a Taylorist ‘trained gorilla’ so much as a self-propelling marionette.

Teige expounds on this at length in the 1928 book World of Laughter, a text on humour, divided between sections on ‘Hyperdada’ and on ‘Clowns and Comedians’. The Teige-designed cover is dominated by an image of Chaplin in The Circus, peering out inscrutably. Interspersed with the text are sharp, strong-lined drawings, either taken from the cultural industry itself (a guffawing Felix the Cat)16 or from satirical protest (various George Grosz images of the grotesque bourgeoisie) and, unsurprisingly, Fernand Léger’s Chaplin sketches for Blaise Cendrars’ Chaplinade.17 Teige’s final gallery of glossier photogravure prints follows a Van Doesburg painting, with its bare, precise abstraction, with an image of Josephine Baker, looking sardonic with her skirt of bananas; circus images by Man Ray and others; and iconic photographs of American comic actor-directors, all of them performing their own specific character. Buster Keaton looks melancholic and effeminate, wanly holding a hand of cards; Harold Lloyd appears as the muscular embodiment of technocratic Americanism, balancing on the girders of a skyscraper’s steel frame; and Chaplin, again taken from The Circus, by contrast sits looking desperately poor and harried. These images between them situate Chaplin in a context of Modernist reduction (De Stijl), comic over-abundance (Baker) and the abnormal personas of his filmic contemporaries. The book itself argues from a similar perspective as the Poetist manifesto published four years earlier – Dada and clowning as a praxis of life, with the technological environment catered for by Constructivism. There is an open, unanswered question in Teige’s inclusion of Chaplin as a Poetist, as in Rodchenko’s poem’s conception of a mass modernity ruled over by technology and mass politics. If Chaplin is ‘outside’ of Constructivism, a phenomenon not part of the faceless mass that is ‘mastered’ by Lenin and Edison, then could he be actively hostile to it? Could he start breaking Edison’s machines, or break ranks with Lenin’s politics? Could his own versions of machines and politics promise something different from, or complementary with, Bolshevism and American technology?

This survey of various exponents of Chaplinism is taken from a wide range of protagonists of the leftist avant-garde. We have Shklovsky’s politically non-committed but aesthetically more disruptive conceptions, most notably ostranenie, and the bared device; Schlemmer’s Germanic, technocratic-Romantic synthesis; Rodchenko’s Bolshevised proclamation of the abolition of art; and Teige’s ideas of avant-garde praxis. Drawing on all of them, certain almost always present features are noticeable. First of all, the notion of Chaplin as a marionette and a machine, his movement somehow new and uncanny, and differentiated from that of his co-stars; second, Chaplin as a universal figure, both in his unassuming, faux-humble posture, and in an (early) ability to play all manner of roles, albeit usually as a subordinate figure in a class sense; third, an employer of avant-garde techniques of estrangement and bared devices; and fourth, Chaplin as a product of the age of ‘Lenin and Edison’, responding to the former in his cinematic representation of the (lumpen)proletariat and the latter in his mechanised movement. This can be seen, then, as not purely an idolatry of an ultra-famous icon of the new mass culture, but as a recognition of a fellow traveller with the leftist avant-garde.18 With that in mind, we will move on to an examination of whether this stands up in the case of his films and those of his less valorised, but still highly important contemporaries, and then analyse the various responses (by the Soviet avant-garde in particular) to these works and their techniques.

Let Me Show You Another Device

I love the theatre, and sometimes feel sad because leadership in the art of acting is beginning to be taken over by the movie actors. I won’t speak of Chaplin, who by some magic premonition we loved before we even saw him. But remember Buster Keaton! When it comes to subtlety of interpretation, clarity of acting, tactful characterisation, and stylistically unique gesture, he was an absolutely unique phenomenon.

Vsevolod Meyerhold, mid-1930s19

Before we turn to the particular forms that Chaplinism took in the 1920s work of Kuleshov, FEKS et al., a selection of films from the period should be analysed in terms of the three major obsessions of Soviet Chaplinists discussed earlier. First, in terms of their presentation of technology as a comic foil, or as a mechanisation of the productions themselves; second, in terms of their devices, their particularly filmic, as opposed to theatrical qualities, the way in which they draw attention to the film form itself and, frequently, mock their ‘high-society, psychological’ competitors; and third, the class relations in the film – specifically, whether or not the claims made by Rodchenko that Chaplin’s work is in some way brought into being by Communism are in any way tenable. We will focus on the short films of the period, both because this allows the opportunity for a cross-section of typical works, and because the frequent time lag between the completion of the films and their likely showing in Germany (and even more so, the USSR) makes it likely that it is these works that were those initially seen by continental Modernists, rather than the more famous features (City Lights [1931], The General [1926], and so forth).

In some of these, you can see exactly what Rodchenko or Shklovsky were talking about. In The Adventurer (1917), Chaplin is an escaped criminal who charms his way through a high-society party, through such ruses as transforming into inanimate objects, such as a lampshade. Another fairly typical short complicates Rodchenko’s contentions: The Bank, which Chaplin directed for Essanay Studios in 1915. In terms of the comic use of technology, Chaplin’s films are generally more subtle than those of his two major competitors, and notably here the gestures, rather than the props themselves, are mechanical, or in this particular instance, bureaucratic, and the film takes place in a particularly corporate space. The first few minutes of the film, however, are most interesting for their bitterly ironic satire on class collaboration. Chaplin, in tramp costume, waddles into a bank one morning, spins through the revolving doors several times, then insouciantly follows the complex combination on the doors to the vault, which he casually opens. The assumption that he is going to steal the reserves that are no doubt kept inside is dispelled when the vault is shown to also contain a uniform and a mop and bucket. The tramp puts on the former, picks up his implements, and goes to work, seemingly without noticing that his obviously parlous predicament could be easily solved by means of the vault’s other contents.

Chaplin as criminal – The Adventurer

Chaplin as object – The Adventurer

No doubt he is considered too harmless and stupid – another phlegmatic ‘trained gorilla’, like F.W. Taylor’s ‘Schmidt’ – to be under suspicion. He clearly, however, has some designs on advancing to the level of clerk, at least. In a movement that supports Shklovsky’s contentions on Chaplin’s mechanised movement very neatly, he treats his janitorial colleague’s arse like a desk drawer, neatly sliding it under the table in a precise, parodic moment. A similar moment comes near the end of the film, during a dream sequence where the tramp foils a robbery (again, co-operating with his superiors20) – using the moustache-topped mouth of a banker as a slot, a receptacle, miming putting paper into it as if it is a postbox. Throughout, the tramp is aggressive to his fellow janitor, who is regularly kicked up the arse and hit with the mop, and seemingly obsequious to the clerks and bosses upstairs. However (as has often been pointed out in studies of the violence in Chaplin’s films), the mop usually fulfils the role of Charlie’s unconscious, ‘accidentally’ hitting the people he is too polite to deliberately strike. It is striking, though, given the relatively benign figure the tramp becomes, how malevolent the earlier Chaplin is, even if this malevolence is mostly presented as being accidental.21

Here, we can see that the familiar melancholic, put-upon Chaplin emerged gradually. You can find him in 1915’s titular The Tramp, and perhaps most fully in Easy Street (1917), a film which combines unusually bleak social criticism for its period with unashamed sentimentality. The opening scenes, with the Tramp crushed and crumpled, crouching in the shadow of the workhouse, are typical examples of this – the marionette gone winsome. The film hinges on him becoming a policeman and defeating the local criminals – something which he manages after an accidental dose of some sort of stimulant from a drug addict’s needle.

Chaplin as tramp – Easy Street

The earlier His New Job (1914) gives more justification to Shklovsky’s theories on Chaplin, what with its baring of various cinematic conventions and devices. Made earlier in 1915, it similarly shows a much more aggressive, and most notably, annoyed figure than the Chaplin of the features, always ready to strike the arses of his adversaries with the ever-present cane. The key element in His New Job is a mocking of the theatrical pretensions of (respectable, non-comic) cinema. The plot hinges on the tramp’s attempt to become a film actor, which he eventually will, by luck and accident. Another auditioning actor reels off his learned speeches from Hamlet, no doubt oblivious to their irrelevance to the silent film, something mocked in a moment where Chaplin with ‘monocle’ mimes a typical thespian. In the feature (which appears to be set in the Napoleonic wars, judging by the costumes, but regardless is clearly an opulent, high-society affair) that is being filmed it becomes obvious that the tramp is unable (despite his best efforts) to remotely convince as a romantic actor. The sword he is given is held in much the same way as the wooden planks he is seen with earlier on, when he is forced to help out the studio’s carpenter, resulting in various of the crew being clouted; and he knocks over, and is trapped by, a large Doric column, smashing up the neoclassical stage accoutrements. Finally, he manages to tear a large (and for the time, revealing) strip off the lead actress’ dress, which he subsequently uses as a handkerchief after he is, inevitably, sacked (although, like almost all his co-stars, she appears to find him sexually irresistible). In this short, much of the comedy is aimed directly at the film-as-theatre, the object of a decade of Constructivist scorn. The acting is inappropriate, the decor anachronistic, the carefully simulated period costumes are torn up – the entire simulated space of the late-Victorian drawing room is gleefully desecrated. Meanwhile, the process of film-making itself is shown as being ad hoc, cheap, and riven with petty hierarchies and stratifications. However, a laugh at high culture, even in this attenuated form, is often an easy laugh – and it is notable that the target is the culture of the bourgeois rather than the place they occupy in the social scale.22

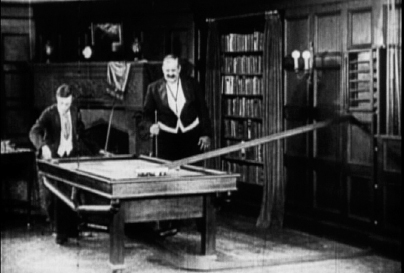

As an explicit baring of cinematic devices, His New Job is far less extensive than Buster Keaton’s 1924 Sherlock Jr., a 45-minute film somewhere between a short and a feature. It acknowledges the disparities in everyday life that film, as a dreamlike space outside of social reality, creates, but does so in a far from schematic manner. Keaton’s protagonist is a film projectionist and porter (and a desperately poor one; an early set piece shows him picking through the rubbish remaining after the spectators have left, finding dollar bills which are invariably then claimed by returning movie-goers) who has daydreams both of courting a woman above his station, and of becoming a detective. After failing miserably in both, he falls asleep, during the projection of another high-toned melodrama set inside a mock-Tudor mansion, with the symptomatic title Hearts and Pearls, its soporific, narcotic function neatly signalled by the name of the production company that appears on screen: ‘Veronal Films Ltd’. The stars morph into Keaton’s previous love interest and her other suitor. Aggrieved, Keaton walks into the film, and is promptly thrown back out of it.

The film itself then takes revenge on this transgression of boundaries by subjecting him to a life-threatening montage. In a sequence that bares the centrality of fast-cutting and montage to film as a medium, while at the same time providing a (remystifying) series of baffling tricks, Keaton is subjected, while staying in the same place, to a change of scene (in rapid succession) from the middle of a road, to the edge of a cliff, to a lion’s den. Then a hyperactive detective film with Keaton in the leading role forcibly replaces the previous melodrama on screen, with a panoply of mechanical devices – Keaton traversing practically every kind of motorised vehicle, with a super-Taylorist precision in timing, as in the moment where a broken bridge is linked by two passing trucks just in time for him to get across. Keaton’s own movement, as Meyerhold rightly points out, is constantly precise and restrained, letting the machines and the tricks take centre stage. Here, the mechanical is both revealed and concealed: there is some clear speeding and reversing of the film, alongside actual stunt work. In the film’s final sequences, where Keaton, now safely out of the film and his dream, gets the girl, the gulf is still present – he watches the screen studiously to find out exactly what to do with his new love, attempting to simulate their heroic gestures. This is in turn thrown back, when the screen blanks out, only to return with the couple holding young children. The last shot shows Keaton looking distinctly unimpressed. Over the course of Sherlock Jr. there is a combination of an assault on (other kinds of) cinematic genre combined with an ambiguous presentation of the social function of cinema (as dream, as educator, as ideologist) which has clear affinities with the Modernist film. Sherlock Jr.’s use both of technological tricks, which need no particular physical gifts, and of acrobatic stunts, is also the key to the Soviet avant-garde’s comic dialectic – a tension between accessibility and artifice on the one hand, and the cultivation of the authentic body on the other; it is a contradiction which would not be resolved.

Buster Keaton’s daydreams, in Sherlock Jr.

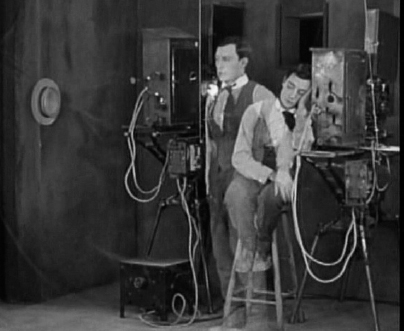

Another affinity with the Constructivists is in a shared fixation on, and involvement in, engineering, as a mechanical basis for filmic experiment and as a joy in machines.23 Like Eisenstein, Keaton had a functional ability in civil engineering, something that is most relevant in two early shorts, One Week (1920), which centres on the prefabrication of housing, and The Electric House (1922). The latter centres on a mix-up of degrees, in which a Buster who is qualified in botany finds himself in possession of a diploma in electrical engineering. He is immediately put to work by the father of the obligatory pretty young woman, in electrifying his entire house. Before the inventions of Edison became prosaic this had far wider implications than lightbulbs and sockets, and the film shares with Russian Futurism a romanticism of electricity (cf. the famous formulation of its egalitarian promise ‘socialism equals Soviet power plus electrification’). So the electric house necessitates every possible area of everyday life being electrified. With an intertitle of ‘let me show you another device’, we are introduced to an automated dining system where food approaches on electrified train tracks, and where the chairs themselves retract from the table mechanically, and cupboards have similar rail systems to get boxes inside and out. The actual engineer, hiding in the generator room, then sets the entire house against the inhabitants, with the gadgets menacing the family to the point where Keaton is eventually flushed out of the house, ending up at the wrong end of the drainage system. Although electricity and engineering are here placed at the service of servility for a decidedly affluent family, its potential is clear both as driver of impossible technologies and as creator of new spaces.

Buster Keaton flicks the switch on The Electric House

Keaton shows another device

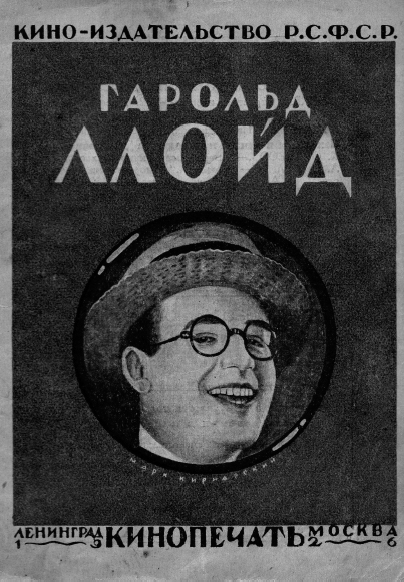

The use of the new space opened up by the technology of the Second Industrial Revolution is the fundamental innovation in the films of Harold Lloyd, who is otherwise ostensibly the most conservative of the three major silent comedians, although this didn’t stop the RSFSR publishing a short tract on his work in 1926, featuring an introduction by Viktor Shkhlovsky, where he contrasts Lloyd with Chaplin, with the former needing to acquire new characteristics, new devices in order to differentiate himself from the English actor-director:

Chaplin fashioned his image by employing the type of the hapless clerk.

Lloyd chose different material as his permanent mask. On screen, he is a young, well-dressed man in glasses.

The glasses saved Lloyd from the fate of being Chaplin’s shadow.

The whole trick of Lloyd’s screen image has to do with a particular shift: he is a comedian with the outward appearance of a girl’s first lover.

Viktor Shklovsky celebrates ‘Garold Lloyd’

Lloyd altered the old character types, the customary conditions of the role. He performed the bit in a different tone. And the bit, as they say in the cinema, got through to the public.24

Lloyd, for Shklovsky, merely uses alternative inanimate objects to differentiate himself; the choice of glasses and neat, Ivy League clothes is largely what distinguishes him from Chaplin’s crumpled suits and bowler hat, enabling the creation of another approach, a new persona, without any psychological interiority necessary, any new ‘personality’. What he does, in fact, is portray a middle-class rather than working-class character, a slapstick comedian you could take to meet your parents. Grandma’s Boy (1923), for instance, showcases a character who is the class antipode of Chaplin’s shabbily dressed chancer or Keaton’s depressive, faintly sinister little man. The entire film hinges on the capture of a tramp who is menacing a small town, albeit a less humble tramp than Charlie’s. However, there is still the fascination with objects, which seem to revolt against Lloyd, as in a fascinating, brief scene where his grandmother’s dresser becomes an obstacle course, with a distorting mirror and a potentially lethal candle, while a central plot device is very uncommon: a false flashback. Nonetheless, this is a tale of a bullied man who triumphs over his tormentors by becoming a better fighter than them, immediately assuming their worldview.

What makes Lloyd relevant for the purposes of this discussion is his use of urban space as a jarring, perilous and fantastical abstraction and absence, in which the skeletal frames of buildings without façades are apt to drop the unwary protagonist into lethally empty space. Never Weaken (1921) is the first of two films (the other being the more famous Safety Last) in which the space of the American city becomes the star. And here too, there is the same mocking of the theatrical we find in Keaton and Chaplin (‘Shakespeare couldn’t have asked for more’, notes the opening intertitle, while literary conventions are also mocked in the painstakingly ornate prose of a suicide note). This skyscraper romance, focused on a couple who work on adjoining blocks, ends in a ballet of girders in which Lloyd, after failing in (that seemingly frequent slapstick event) a farcical suicide attempt via a gun wired up to the door of an office, is lifted in his Thonet chair onto part of the steel frame of a skeletal skyscraper. Blindfolded, he immediately assumes he has been lifted up to heaven, as when he opens his eyes the first sight is the stone angel carved onto the corner of his office block. The next ten minutes or so are a remarkably abstract play of mechanical parts in which the stunts are the only ‘human’ element, albeit in a particularly superhuman form. By the end, he still thinks he’s in this vertiginous girder-space even when he is lifted onto the ground, reaching for a policeman’s leg as if it were the next girder along.

On this brief assessment, Chaplin’s films often seem less mechanically striking than those of his immediate contemporaries, although it is only Chaplin who actually convincingly mimes a machine, taking the machine as a measure of human interaction.25 Lloyd and Keaton are always fundamentally untouched by their encounters with malevolent technologies. With Chaplin the machine becomes something immanent. In that case, it is telling that he becomes the principal model for the new techniques of film-making and acting introduced in the Soviet Union. Absurd as a Taylorised Chaplin might appear (in the context of his later parody of scientific management in Modern Times), it is surely this which makes him more appealing to Soviet Taylorists. The place we can find this merging of Taylor and Chaplin is in the discipline of ‘Biomechanics’, developed by the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold.

Harold Lloyd walks the steel frames in Never Weaken