2

Red Clowns to the Rescue:

Biomechanics in Film, Factory and Circus

I got the chance to see a few other productions, on nights off, and afternoons when I had no matinee. Soviet vaudeville was heavy on acrobats, wire walkers, kozatski dancers, jugglers and trained animals. Actually, the People’s Vaudeville was a watered-down stage version of the People’s Circus. The circus was by far the most popular form of entertainment.

Harpo Marx, on a tour of the Soviet Union in 19331

Most people are still unaware that many of the successes of our leftist cinema originate from the circus and acrobatics.

Sergei Tretiakov, ‘Our Cinema’, 19282

Proletcult. This theatre developed on acrobatic lines and its methods began to approximate to those of the circus. This phase is now passing. The theatre has its headquarters at the Colusseum, Christy Prood. Its scenery and stage apparatus are so designed as to be readily converted, and at the same time to give opportunities for acting on several different levels. This portable property equals performances to be given at the Workers’ Clubs three nights a week.

Teachers’ Labour League, Schools, Teachers and Scholars in Soviet Russia (1929)3

Joyous Rationalisation

The most notorious depiction of the Soviet enthusiasm for the industrial scientific management usually summarised as ‘Taylorism’ is in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1920 novel We, unpublished in the USSR until the 1980s, although the author gave public readings from it in 1923. It shares its name with a play by the Constructivist theorist and designer Alexei Gan, and the similarity of title is in no way coincidental. We is a novel of Soviet Taylorism taken to its illogical conclusion. Set in the twenty-sixth century, it purports to be the diaries of D-503, an inhabitant of a giant city where the population live in glass skyscrapers and adhere to a ‘table of hourly commands’. He is an engineer by profession, builder of the ‘Integral’, a spacecraft designed to take the new rationalist society to other worlds altogether. Zamyatin conceives of this ‘One-State’ as a vast, beautiful ballet mécanique. D-503 writes:

this morning I was at the launching site where the Integral is under construction – and I suddenly caught sight of the work benches. Sightlessly, in self-oblivion, the globes of the regulators rotated: the cranks, glimmering, bent to right and left; a balanced beam swayed its shoulders proudly; the blade of a gouging lathe was doing a squatting dance in time to unheard music. I suddenly perceived all the beauty of this grandiose mechanical ballet, floodlighted by the ethereal, azure-surrounded sun.4

Taylorism has here achieved the status of a kind of official state philosophy. D-503 is amused at the philosophical myopia of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, stating – ‘Taylor was, beyond doubt, the greatest genius the ancients had’, although ‘he had not attained the final concept of extending his method until it took in the entire life-span, every step and both night and day.’5 He watches and participates in collective exercises, or rather, cells of rhythmic Taylorised happiness. All beauty in the One-State is based on the eroticism of geometry, on the intersections of planes, on discrete colours and shapes in conflict and alignment. Physical desirability is based on abstraction. A woman whom our diarist is attracted to is described as being ‘made up entirely of circumferences’.6 Collective work and collective action is the highest form of beauty, a merging into one technologised organism, with no divisions, no labour hierarchy. The designer of the Integral, our protagonist, joins in the building work, struck by the beauty of the labour process:

the workers below, in conformance with Taylor, regularly and rapidly, all keeping time, were bending, straightening up, turning like the levers of a single enormous machine [. . .] I was shoulder to shoulder with them, caught up in a steel rhythm.7

This is surely satire aimed at Proletcult and Constructivism, at Gastev, Meyerhold, Gan, Rodchenko, Stepanova and their circle, and Zamyatin is able to convey the sheer excitement they found in the industrial process, and their intent to make of it a new form of art. What he adds, however, is the central dictatorial figure, The Benefactor, a cultic element the Constructivists would resist, but one which D-503 seems unconcerned by. The Benefactor is ‘a certain something derived from the ancient religions, something purifying like a thunderstorm or tempest’.8

The Constructivists, like the One-State, certainly did attempt to transfer Taylorism into the aesthetic sphere. We will find, however, that in the process they created something that did not evoke the Platonic, frozen world described in We, but rather proposed something rough, changeable and comic.

Some observers of the early Soviet Union were horrified by the manner in which it tried to extend American industrial methodologies, taking them out of the factory into everyday life and into art. A well-informed, if politically typical, observer, René Fülöp-Miller, writes of how,

in spite of all this fantastic veneration for Chicago and ‘Chicagoism’, the Bolsheviks have many faults to find with their model; the chief defect being the lack of the true political form, the dictatorship of the proletariat, which alone is able to develop society into the longed-for ‘complete automaton’. Only Bolshevism can give the final perfection to this technical wonderworld. For even in America mechanization is still confined to economic life, limited to the factories. [. . .] The American, it is true, was the first to create the mechanistic-technical spirit, but he is trying to sneak away from its social consequences, and aims at continuing to preserve outwardly the soulful face of the good-natured, honest man.9

In an account which anticipates both Cold War and post-89 paradigms, the use of cybernetic techniques outside of the immediate production process portends the elimination of the conception of the ‘human’ itself.

Yet if biomechanics, the form of mechanised, Taylorised acting developed in the theatre of Vsevolod Meyerhold from the early 1920s onwards, is an imposition of industrial domination to the point where it conspires to bleakly mechanise even entertainment, why is it that accounts of biomechanical studios seem to present something so enjoyable, almost idyllic? The American artist Louis Lozowick, for instance, presents his visit as follows:

The first place we came to was a middle-sized room, rather dimly lighted and full of young people noisy with talk and laughter. Most of them seemed to be engaged in what appeared to be physical exercises of all kinds – swinging over bars, leaping over obstacles, doing acrobatic stunts on a ladder, making somersaults, and suddenly exploding with laughter when something did not seem to go right. Was this a gymnasium? I asked. No, it was a class for young actors in biomechanics, the discipline invented by Meyerhold and very popular among the young. Briefly, biomechanics required of the actor that he be complete master of his ‘biologic machine’ in all its faculties and functions. The actor should have such perfect control of his body that he could pass instantly from motion to repose, from fencing to the dance, from gesture to pantomime, and from walking to acrobatics.10

This doesn’t appear to be the Taylorist learning of small, exact movements requiring little effort and less skill, but a peculiar combination of sport and circus. Lozowick clearly has no American referent for such a thing, yet the young actors seem to assume that he must. ‘When they learned that there was an American in their midst,’ he recalls, ‘they surrounded me and showered me with questions. “What kind of training do the actors get in America? How do they make their living? Do they know about biomechanics?”’ They do not, of course – this is another Soviet ‘American’ invention.11

Biomechanics is a comedy of technology, and hence is a fusion of Taylorism and what Meyerhold himself would codify in 1936 as ‘Chaplinism’. It is, not without reason, the former of those two who has been privileged in readings of biomechanics. Trotsky, for instance, in his remarks on Meyerhold in Literature and Revolution, considered this a symptom of the contradictory over-reaching of the ‘Futurists’ due to Russia’s combined and uneven development, a strange accident, whereby the deployment of a strictly industrial system in art achieves an ‘abortive’ effect. Others, while not so harsh, have also noted only the Taylorist element of the biomechanical system. Richard Stites’ otherwise comprehensive Revolutionary Dreams, for instance, doesn’t spot that American comedy was a source of bio-mechanical ideas, and that slapstick acrobatics were perhaps a greater element than the incipient militarism he notes. Stites does however rightly record that Meyerhold was a committed Taylorist, and a member of the League of Time, one of two quasi-Taylorist groups active in the early Soviet 1920s, and the affinity of his theories with the leader of the other, Alexei Gastev of the Central Institute of Labour. Similarly, he writes, biomechanics is a regime of:

alertness, rhythmic motion, scientific control over the body, exercises and gymnastics, rigorous physical lessons in precision movement and co-ordination – in short, ‘organised movement’, designed to create the ‘new high-velocity man’.12

The new high-velocity man (who will live in the ‘newly-built house’) could be the Taylorised worker, or he could just as easily be Harold Lloyd. A retrospective argument can help illuminate the claim that biomechanics is a form of technological comedy. In 1936 Meyerhold wrote a lecture titled ‘Chaplin and Chaplinism’. This article is overshadowed by the beleaguered director’s need to justify himself against the orthodoxies of Socialist Realism, which he does by accepting them in part, and then refusing them with the next argument (an approach which evidently did him no favours, given his eventual murder by the state). In this essay he compares his own earlier work – the biomechanical productions of the 1920s, from The Magnanimous Cuckold (1922) to The Bed Bug (1929) – to the early silent comedies of Chaplin, in that they both share a particularly mechanical bent. The early films – Meyerhold mentions His New Job – were considered to ‘rely on tricks alone’; but, like the repentant Meyerhold looking over his shoulder at the NKVD, Chaplin then repudiated such frippery with the pathos of The Gold Rush. ‘He condemned his own formalist period, rather as Meyerhold condemned Meyerholditis.’13 Yet earlier in the same argument he has intimately linked his development of biomechanics with Chaplin’s privileging of movement over the inherited devices of the conservative theatre. After noting that Chaplin began to reject ‘acrobatics’ and ‘tricks’ from around 1916, he writes:

As a teacher I began by employing many means of expression which had been rejected by the theatre; one of them was acrobatic training, which I revived in the system known as ‘biomechanics’. That is why I so enjoy following the course of Chaplin’s career: in discovering the means he employed to develop his monumental art, I find that he, too, realised the necessity for acrobatic training in the actor’s education.14

So while he is making a highly ambiguous and guarded repudiation of biomechanics, he essentially defends it by aligning it with the comic acrobatics of the early Chaplin and the Mack Sennett Keystone comedies. This can also be seen in his employment throughout the 1920s of Igor Ilinsky, an actor whom Walter Benjamin (in the Moscow Diary) rather unfairly considered to be an extremely poor Chaplin impersonator, as a means of introducing some kind of Chaplinism to the Soviet stage; but there is an implication there too in the original theoretical justifications of biomechanics. In this, and in many other pronouncements on the affinities between comedy and technics, the comic element is mediated through the circus (which, as we will see, was regarded by Eisenstein and Tretiakov as a proto-cinematic form).

This is perhaps encapsulated in the distinction Meyerhold establishes between ‘ecstasy’ and ‘excitability’, with the former standing for all that is mystical, religiose and of dubious revolutionary value, and the latter standing in for dynamism, movement, comedy.15 More to the point, his conception of biomechanical labour, both inside and outside the theatre, is actually quite far from Taylorist in its conception, something critically but correctly noted by Ippolit Sokolov, who according to Edward Braun regarded biomechanics as ‘“anti-Taylorist” [. . .] rehashed circus clowning’.16 Similarly, actual Fordists were unimpressed with Gastev’s attempt to conjure up an entire system of life out of their industrial management techniques, precisely because it had comic elements, because in some ways it was not serious; when emissaries from the Ford Motor Company visited his Institute, they found ‘a circus, a comedy, a crazy house’ and a ‘pitiful waste of young people’s time’.17 Following this precedent, biomechanics is a complete revaluation of Taylorism to the point where it attains the quality of circus clowning. To illustrate this point, we could compare Meyerhold’s conception of work with that of Taylor himself, and of Henry Ford, that great proponent of the scientific management of labour and Soviet icon.18

Fordist labour is predicated on the near-total elimination of thought in work; something which some, such as Gramsci, regarded as freeing up potential for revolutionary organisation, but which undoubtedly created bleak, relentless work environments. An account of Fordist labour from the worker’s perspective, such as Huw Beynon’s Working for Ford, for instance, stresses precisely this aspect.

Working in a car plant involves coming to terms with the assembly line. ‘The line never stops you are told. Why not? . . . Don’t ask. It never stops. When I’m here my mind’s a blank. I make it go blank.’ They all say that. They all tell the story about the man who left Ford to work in a sweet factory where he had to divide up the reds from the blues, but left because he couldn’t take the decision making. Or the country lad who couldn’t believe that he had to work on every car: ‘oh no. I’ve done my car. That one down there. A green one it was.’19

Sokolov and the Ford delegation were right – this doesn’t bear much resemblance to the biomechanical studio.

In the 1922 lecture ‘The Actor of the Future and Biomechanics’, Meyerhold clearly regards work as something that has to be completely transformed in a socialist society, eliminating drudgery and fatigue and reinstating thought. Rather tellingly, by contrast with Taylor or Ford, his model is the skilled worker. This can be seen even in the most seemingly Taylorist statements.

However, apart from the correct utilisation of rest periods, it is equally essential to discover those movements in work which facilitate the maximum use of work time. If we observe a skilled worker in action, we notice the following in his movements: (1) an absence of superfluous, unproductive movements; (2) rhythm; (3) the correct positioning of the body’s centre of gravity; (4) stability. Movements based on those principles are distinguished by their dance-like quality: a skilled worker at work invariably reminds one of a dancer; thus work borders on art. This spectacle of a man working efficiently affords positive pleasure. This applies equally to the work of the actor of the future.20

While an American Taylorist might agree with these four points, the use to which they are put, and the aesthetic pleasure that it produces in both the worker and the spectator, would be wholly alien to him.

Taylorism essentially rests in the rationalisation of drudgery, and the implementation of precise rules for unskilled work. This is no doubt why Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management centres on pig-iron handling as its main example, in that it proves that even the most thoughtless work, based purely on brute strength, idiotic work – especially this kind of work – can be made ‘scientific’, that is, reduced to a series of speeded-up, physically amenable and repetitious movements, that which can be performed by, in Taylor’s admirably unromantic phrase, an ‘intelligent gorilla’. Meyerhold argues for the worker as something complete, who rationalises his work to the point where his work becomes an aesthetic phenomenon. Taylor and Ford are, quite unashamedly, interested in the unthinking worker.21

In My Life and Work (which went into several Soviet editions in 1925 alone, Stites notes) Ford (or rather his ghost-writer) is candid about his own horror of the labour which takes place on his assembly lines:

Repetitive labour – the doing of one thing over and over again and always in the same way – is a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind. It is terrifying to me. I could not possibly do the same thing day in and day out, but to other minds, perhaps I might say to the majority of minds, repetitive operations hold no terrors.22

So there are some who are made for the life of the mind, and some for a life of labour; any attempt to bridge the two is unimaginable, and merely breaks up the worker’s otherwise contented existence, as with those agitators who ‘extend quite unwarranted sympathy to the labouring man who day in and day out performs almost exactly the same operation’.23

There isn’t any attempt to romanticise this pattern of work, however – merely a repeated claim that first, there are people who are ‘made’ for this kind of labour, and second, that those who do it have no objection to it (and those who do object can easily be put to work in the more creative areas of the Ford Motor Company). The vast difference between this and Meyerhold’s skilled, balletic worker, in perfect control of mind and body, should be obvious. Ford reiterates that he employs all manner of disabled workers in his factories, because skill is fundamentally irrelevant. ‘No muscular energy is required, no intelligence is required.’24 ‘Taylorisation of the theatre’ shares with actual Taylorism in the factory a fixation with the precise mapping of movement, the speeding up of that movement, and the elimination of the extraneous – but it comes at this from an entirely opposed position, for all Meyerhold’s protestations.

Making-Difficult

The Circus, however, which is the foundation of the theories of ‘attractions’ developed under Meyerhold’s influence by Tretiakov and Eisenstein, is far closer to the biomechanical theory than is Taylorist practice. They are both forms of work based on a remarkably regimented control of the body, and on spectacle. This is after all a theatre based on ‘physical elements’, rejecting both ‘inspiration’ and ‘the method of “authentic emotions”’. Rather than the Stanislavskian method, we have as potential aids to biomechanical acting ‘physical culture, acrobatics, dance, rhythmics, boxing and fencing’.25 All of these forms, like the circus, or the intricate mesh of engineering and acrobatics that makes up the comedies of Buster Keaton, are based (just as is pre-industrial craftsmanship) on what Shklovsky calls difficulty, on physical feats, as much as they are on the regimented, precisely controlled motion of Taylorism. In his discussion of ‘The Art of the Circus’, he notes that ‘plot’ and ‘beauty’ are irrelevant to the circus, and that its particular device is in this difficulty, in the very fact that ‘it is difficult to lift weights; it is difficult to bend like a snake; it is horrible, that is, also difficult, to put your head in a lion’s jaws.’26 So this, again, is skilled work, something which cannot be emulated easily. Its appeal rests on the spectacle of ‘horrible’ feats being performed, and on the veracity of those feats.

Making it difficult – that is the circus device. Therefore, if in the theatre artificial things – cardboard chains and balls – were routine, the spectator would be justifiably indignant if it turned out that the weights being lifted by the strong man weighed less than what was written on the poster [. . .] the Circus is all about difficulty [. . .] most of all, the circus device is about ‘difficulty’ and ‘strangeness’.27

This difficulty and strangeness is implied to be similar to the difficulty and strangeness of Futurism, something which is then wholly taken up by Meyerhold’s students, Tretiakov and Eisenstein, although the former comes to have doubts about its political efficacy other than as a sort of shaming of the unfit audience who are incapable of undertaking such feats. It is this, as already noted, which is the crux of the problems in Constructivism’s comic Americanism. There is the trick, the baring of the device, the impossible geographies and improbable movements created purely via the mechanical means internal to the cinema and to montage; and there is the ‘difficult’ circus trick, which is reliant on the particular physical training of the actor or circus performer, which relies on the perfection of the real physical body. In this case, if the audience are not able to perform these feats, they may be able to enjoy the spectacle of someone else living in the ‘newly built house’, but they themselves will still not be able to occupy it.

An interesting defence of the ‘difficult’ form of trick as a kind of dialectical reversal of reification, or an ‘anticipatory memory’ of a world without reification, can be found in Herbert Marcuse’s 1937 essay ‘The Affirmative Character of Culture’. Marcuse claims that:

when the body has completely become an object, a beautiful thing, it can foreshadow a new happiness. In suffering the most extreme reification man triumphs over reification. The artistry of the beautiful body, in effortless agility and relaxation, which can be displayed today only in the circus, vaudeville, and burlesque, herald the joy to which man will attain in being liberated from the ideal, once mankind, having become a true subject, succeeds in the mastery of matter.28

This seems closest of all to Meyerhold’s conception of machinic movement – the treatment of the body as an object to the point where objectification becomes reversed. This is a tentative, and perhaps unsuccessful attempt to fuse the apparent industrial rationality of Taylorism with the production of movements based on joy rather than on eight hours of the same movement for the purposes of an unusually high pay cheque. On another level, what Marcuse describes, this ‘artistry of the beautiful body’, could be seen around the same time in the aestheticised, classical cinema of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938), whose smoothness and humourlessness is otherwise very far from Meyerhold’s conceptions; the concentration on the deliberately farcical, ‘low’ form of the circus, rather than Riefenstahl’s lofty Hellenism. Yet as long as it remained something based on ‘circus tricks’, despite the organic connection with proletarian culture this might provide,29 biomechanics remained something outside of everyday life, based on spectacle and amazement, at a safe distance. The truly utopian implication of biomechanics lies elsewhere – in the possibility that it would make the factory more like the circus and the circus (and the associated popular forms – vaudeville, cinema) more like the factory, thus closing this gap. Yet work still remains the common thread linking the two, despite the possibility that Taylorism could actually reduce labour.30

The circus elements of biomechanics would be emphasised by Eisenstein in 1923’s ‘The Montage of Attractions’, an essay so extensively analysed that another discussion of it here would be fairly superfluous.31 Eisenstein’s ideas on ‘attractions’ – moments of ‘emotional shocks’ – were developed in collaboration with Sergei Tretiakov on plays like 1923’s Gasmasks and Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man, but Tretiakov’s own version of the ideas has not been given anything like the same attention. ‘The Theatre of Attractions’ (1924) has an intense focus on the attraction’s utility in the class struggle, noting that ‘despite the tremendous importance of biomechanics as a new and purposive method of constructing movement, it far from resolves the problem of theatre as an instrument for class influence’ ;32 the response to this appears to be a move away from the Constructivist slapstick of Magnanimous Cuckold or the Eisenstein collaborations, in favour of the ‘precise social tasks’ of instilling particular agitational effects in the audience via the attractions.

So while montage is derived from ‘the music hall, the variety show, and the circus program’, Tretiakov notes that in that form ‘they are directed towards a self-indulgent and aesthetic form of emotion’, irrespective of the disjunctive effects of their difficulty and strangeness. The movements in Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man are ‘based on acrobatic tricks and stunts and on parodies of canonical theatrical constructions from the circus and the musical’. This can provide part of the intended agitational effect, provoking ‘audience reflexes that are almost entirely objective and that are connected to motor structures that are difficult or unfamiliar for the spectator’, while he claims that individual attractions ‘operate as partial agit-tasks’. The flaw, however, appears to be precisely in the audience reaction to the very difficulty of the attractions, in their inability to perform them, as ‘expressed in statements such as “what a shame that I can’t control my movements like that”, “if only I could do cartwheels” and so on.’ The result of this is then claimed to be much the same as that produced by a performance of Ibsen’s Brand, the spectator ‘depressed from all Brand’s thrashing about’. Although Tretiakov evidently thinks that the audience will be ruing ‘their own existing physical shortcomings’, he acknowledges that it is precisely the emphasis on the spectacle of difficulty that is the problem with inspiring an active response in the audience.33

Boris Arvatov had claimed in LEF in 1924 that the new theatre had a political effect through its exemplary effect on the audience:

the theatre must be reconstructed on the foundations of an overall social, extra-aesthetic science and technology (physical culture, psycho-techniques and so on) with aesthetic formalism expelled from it. Only those artists who have grown up in this new ‘life-infused’ theatre will be able to give us a strictly utilitarian, Taylorised shaping of life, instead of the theatricalisation of life. [my italics].34

Tretiakov seems to argue that this has been a failure. For all the defamiliarisation produced by circus Taylorism, the effect is much the same as produced by, for instance, the stunts of Harold Lloyd or Buster Keaton. The world may seem momentarily different, may have been made momentarily strange and exciting, yet the everyday is still untouched, and the mere reaction of thrill or awe is not enough. This prefigures Tretiakov’s subsequent development of the more active ‘operative’ theories of the later 1920s, where spectacle decreases in importance to the avant-garde, in favour of participation, wall-newspapers and worker-correspondents.

FEX as Engineers of Spectacle

The Technique=Circus, the Psychology=Head over Heels

The Factory of the Eccentric Actor (FEX),

‘Eccentrism’ (1922)35

We wanted to create a show in which a series of tricks would unite the elements of circus, jazz, sport and cinema. Our ideal actor was Chaplin. We considered that Eccentrism was the surest way to ‘Americanise’ theatre, to give the theatrical action the dynamics required by the 20th century – the century of unheard-of velocities.

Leonid Trauberg of FEX36

The actual use of biomechanics, derived as it is from a form of popular art, when used in conjunction with popular Americanism, seems to have become inadvertently politically contradictory. The reports of the production of D.E. – Give Us Europe, for instance, seem to suggest that, like One Sixth of the World, the play sets up an opposition between the decadence of the United States, represented by jazz and the foxtrot,37 and the nobly marching Komsomol, in a play where the USA and the USSR fight over Europe. So the ‘West’ then had the monopoly on dance in an erotic, as opposed to acrobatic sense, with the biomechanical movements of the young communists appearing merely militaristic. Edward Braun, drawing on contemporary accounts, claimed that ‘the scenes in “foxtrotting Europe” [were] far more energetic and diverting’ than those of the Red Fleet and the young biomechanists.38 Mayakovsky was particularly scathing about the onstage juxtaposition of an (actual) jazz band and the (actual) Red Fleet, mocking its military pretensions as ‘some kind of theatre institute for playing at soldiers’.39 The promise of the Theatre of the Eccentric Actor was, in part, that they could perform a synthesis – one whereby the Reds would not necessarily have to be the incursion of order and power; the link between the biomechanist and the foxtrotter.

Eccentrism was an amalgam of jarring techniques, modernist disorientation, Keystone Kops slapstick and Taylorist mechanisation, albeit stressing their disruptive elements rather than the nascent sobriety of biomechanics. Published by Grigori Kozintsev, Leonid Trauberg, Sergei Yutkevich and Georgi Kryzhitsky while still in their teens, and thrown at Petrograd passers-by from a moving car, the 1922 Manifesto of the Eccentric Actor is a playful counterpoint to Constructivist hardness: self-referential and witty, undercutting its violence with a wilful absurdism. Importantly, the Eccentric Manifesto serves as a major corrective to the still depressingly prevalent view of the 1920s avant-garde as haughtily aloof from ‘popular culture’, wherein the artistic ‘vanguard’ in a parody of Leninism attempts to ‘improve’ its audience. Regardless, the hostility of Eccentrism to ‘high’ art forms is surely not in doubt. Eccentrism, as employed by the acting studio-film collective The Factory of the Eccentric Actor (FEX) first of all abolished the theatre’s preoccupation with subjectivity, with the depiction of a character’s inner torments. In the Manifesto this is best expressed by a comparison between an actual theatrical review (‘captures all the fine psychological nuances of fading passion with great sensitivity’) and an imaginary one of one of their revues (‘after four false starts Tamara tears off into the distance’).40

The Manifesto, with its innumerable references to Chaplin and the circus, is also notable for its unconcealed infatuation with the imagined USA and its unambiguous Proletkult-influenced Communism where revolution and revolutionary art ‘spills into the streets’ rather than being limited to legislation and regulation of industry. This is then accompanied by a love for the ephemeral products of base capitalism.

WE VALUE ART AS AN INEXHAUSTIBLE BATTERING RAM SHATTERING THE WALLS OF CUSTOM AND DOGMA. But we also have our forerunners! THEY ARE: The geniuses who created the posters for cinema, circus and variety theatres, the unknown authors of dust-jackets for adventure stories about kings, detectives and adventurers; like the clown’s grimace, we spurn Your High Art as if it were an elasticated trampoline in order to perfect our own intrepid salto of Eccentrism!41

The theoretical preoccupations of the other proponents of a Chaplinist-Taylorism are here, but it’s clear that the emphasis is on a kind of cultural revaluation of popular art and ‘trash’ to the point where, rather than revolutionary art drawing from it while mechanising it, calming it down, it accelerates the process, taking the cultural forms of Americanised capitalism in the context of the NEP’s mixed economy as something which, like the ‘socialist’ elements of the economy, is hostile to the restoration of bourgeois values exemplified by the psychological, high-society play/picture as the cultural form enjoyed by the NEP man.

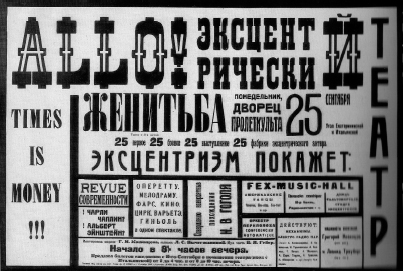

Given their evident preoccupation with the poster, it would be instructive to look at the poster for their first (of two) theatrical production, of Gogol’s The Marriage.42 The typography is obviously circus influenced, as is the style – a crowding of declarations and promises (or disclaimers, such as explaining that the production was ‘not according to Gogol’), with certain stretches of text in large print. Most interesting for our purposes is that there were various sections of text in a dubious English. One area declares the ‘FEX-MUSIC-HALL’ (Chaplin’s old school), while one of the areas of the grid is filled with the Taylorist exhortation ‘TIMES IS MONEY!’, which both promises a few stereotypes of Americanism, an oblique joke at NEP capital, and the accelerated pace the Eccentrist borrows both from the speed, violence and cynical humour of the American comic film, and from the accelerated mode of production – something also indicated by Kozintsev and Trauberg spurning the title of ‘directors’ in favour of ‘Engineers of the Spectacle’. The play itself, as if to declare that the eventual intention of the FEX was to branch out into film production, included projected excerpts from American comedies. Katerina Clark’s list of the attractions (taken from her translation of reminiscences by Kozintsev) suggests biomechanical theatre becoming an organised chaos:

Original Poster for the FEX-MUSIC-HALL

Figures dressed in garish clothing exchanged shouts and reprises about topical issues; they sang couplets and acted out strange pantomimes with dances and acrobatic feats. The affianced pair from Gogol (in conventional theatrical guise) were mixed in with constructions moving about on wheels. Then, in a flash, the backdrop was changed into a screen onto which was projected a clip of Charlie Chaplin fleeing from the cops. Actors dressed and made up in the same way as those on screen burst onto the stage to act in parallel play with the movie. A circus clown shrieking hysterically turned on a salto mortale right through the canvas of the backdrop, while ‘Gogol’ bounced around on a platform with springs from which he was propelled to the ceiling.43

So here we have circus-as-defamiliarisation in an extreme form, where the procession of jarring attractions is adapted to political agitation and to a technologised burlesque on the Russian classics; we also have a return of cinema to its original place as just such an attraction, something that would have accompanied the clowns and lion-tamers. The fixed nature of cinema, as a discrete object of contemplation, flickering out from the dark, is disrupted by combining it with the actual movement of figures on stage, so that – as in the circus itself – falling into a trance is impossible, in populist prefiguring of the Epic Theatre. Nonetheless, it would seem that the theatre was only a stage on the way to the more genuinely proletarian entertainment of the cinema, and in the 1924 article ‘The Red Clown to the Rescue!’44 Trauberg quite specifically called for the film studios to allow the FEX to make a film.

The earliest surviving example of the FEX’s foray into film-making (the debut, The Adventures of Oktyabrina [1924], is lost), and the most clearly ‘Eccentrist’ in its conception, is The Devil’s Wheel (1926), a cut-up comedy of the Leningrad lumpenproletariat, centring on an amusement park and the descent into the dissolute of a Red Army man (hence the early title Sailor from the Aurora, the cruiser used in the October Revolution). It establishes a tension from the very start between its socially redeeming aims and the joy with which the caricatured criminal underworld is depicted – and it does this through the depiction of a very particular kind of urban space. The first scene shows a Leningrad apartment block, surrounded by rubble, with blasted -out windows which are suddenly filled with people dancing, fighting and kissing. While, no doubt, this is intended at one level as a depiction of squalor and poverty, it also serves as a celebration of teeming urban life, and the fantastical delineation of a new multi-storey architecture of clarity, visibility and play. There is a deliberate dialectic set up between the everyday, and what on paper sounds like a conventional love story, and the montage of attractions themselves, which present the everyday via the defamiliarisations of jump-cuts and cheap but effective tricks, described by Jay Leyda as a deliberate ‘clash’ between realism and an ‘eccentric treatment’.45 Nothing is too crass for the FEX in this film – and so circus crassness is taken to the level of non-objectivity.46 While many of its tricks rely on such obvious props as sticking fireworks in the background, having its characters walk through halls of mirrors, filming the spinning wheels to the point where they become abstract, or focusing on the abstraction of the patterns on the heroine’s dress, the use of an amusement park as a setting provides a ready-made series of attractions to exploit.

The sailor from the Aurora is tempted in The Devil’s Wheel

The contradiction in Eccentrism between its Bolshevism and its fixation on the socially dubious comes out in certain moments in The Devil’s Wheel. At one point the hoodlums, led by a circus magician named ‘Mr Question’, go to attack a Workers’ Club, and one briefly wonders which side Kozintsev and Trauberg would want to win in that particular fight, such is the intrigue and excitement with which the underworld is portrayed. The suggestion is that the world inhabited by these characters, with their obsession with thrill and sensation for its own sake, is the true and correct way of experiencing technologised everyday life. The manifesto itself hails ‘the cult of the amusement park, the big wheel and the switchback, teaching the younger generation the BASIC TEMPO of the Epoch’. These settings are described by Barbara Leaming as a kind of New Space – which we might suggest is of a different but analogous kind to the abstract grids of the Harold Lloyd films -the creation of ‘an alternate world, an eccentric locus of playful subversion. In the amusement park, the logic and meaning of the everyday world are suspended.’47 So what does it mean for the veteran of the October insurrection to be dropped into this space? It is not treated with moralistic disgust, but it is clear that it is something that must be destroyed, albeit, it would seem, with some regret, and perhaps utilising some its features afterwards (hence the carnivalesque depiction of the Paris Commune in The New Babylon three years later). Appropriately, the destruction of fairground underworld is itself given a strange, acrobatic treatment, where the gangsters fall out of the windows of the cramped apartment block we see at the start of the film, ‘like a swarm of clowns descending to the sawdust’.48 After their fall, something is lost.

The New Stupidity

I do not know whether the stage needs biomechanics at the present time, that is, whether there is a historical necessity for it. But I have no doubt at all – if I may speak my own point of view – that our theatre is terribly in need of a new realistic revolutionary repertory, and above all, of a Soviet comedy [. . .] we need simply a Soviet comedy of manners, one of laughter and indignation [. . .] a new class, a new life, new vices and new stupidity, need to be released from silence, and when this will happen we will have a new dramatic art, for it is impossible to reproduce the new stupidity without new methods.

Leon Trotsky, Literature and Revolution (1924)49

Meyerhold’s biomechanical works tend to either be revolutionary celebrations such as D.E., or peculiar adaptations of the classics such as The Magnanimous Cuckold; and when, at the end of the 1920s, he moves into social satire with Mayakovsky’s Bed Bug and Tretiakov’s eventually unproduced I Want A Child, he faces harsh opposition from state critics. So could the new American-Soviet forms really be used to critique the ‘new vices and new stupidities’ of the bureaucratic, unfinished revolution? The first major Soviet film comedies do not quite conform to Trotsky’s prescriptions – the stupidities portrayed are almost entirely those of the Western perception of Bolshevism, as opposed to the indigenous stupidities of bureaucracy and NEP. Lev Kuleshov’s Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) was the fruit of several years of experimentation on the part of a ‘Collective of Failed Actors’ who had all been rejected at their examinations (hence Kuleshov’s later claim that the film was motivated by a climate where ‘everyone defended the theatricalisation of the cinema, the Moscow Art Theatre was law, and only in it could be seen future production possibilities50), and is a feature-length farce concerning the titular American visitor, who, visiting the ussr and assuming from the Western press that he will be faced with ruthless, bloodthirsty Bolsheviks, brings with him a cowboy relative (played by the boxer Boris Barnet) but is kidnapped by the same sort of charismatic, eccentric underground troupe that would feature two years later in the FEX’s Devil’s Wheel.

The film contains a multitude of tricks and stunts, most of which are indebted to the ‘American montage’ that Kuleshov consistently argued for. Mr West’s Ivy League haplessness and round spectacles are immediately reminiscent of Harold Lloyd, his clothes appear as a kind of engineer’s garb, and a car is fixed in the first few minutes (that American technological expertise), while high-wire acts evoke both Lloyd and the circus. The overwhelming impression of Mr West, though, is one of sheer speed, from the fast-cutting to the incessant car chases – both of which seem far more indebted to the example of Mack Sennett’s pre-1920 Keystone Kops series than the more sophisticated work of Keaton or Chaplin. Other devices seem to have been arrived at without American example. The montage of intertitles onto the action, as well as speeding up the action and lessening the literary remnants, have a similar effect to Rodchenko’s work on Vertov’s Kino-Eye in the same year, treating the graphic elements of the film as an integral element, creating disruptive, anti-illusionist, defamiliarising parallels with the typographical experiments on the page in Kino-Fot or Rodchenko-Mayakovsky’s Pro Eto. Kuleshov intended at least some of the borrowings and lurid details to have an educational or at least parodic effect, albeit largely at the expense of German expressionism rather than the American comedy, in moments which are intended to be parodies of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Dr Mabuse The Gambler (1922):

in these scenes we wanted to expose the fundamental and essential falsity of psychological fiction cinema and we were trying to show that the regular organisation of acting and montage work will give us the opportunity to get the better of every style and character of production, and in particular the American and German examples.51

Regular organisation – so even the seemingly improvisational scenes where the underworld remnants leap around and generally assault the sensibilities of Mr West are created in a mechanically precise manner.

Kuleshov’s collective torment Mr West with great relish, with Aleksandra Khoklova as a dubious ‘countess’ being particularly eccentric and gleeful. Again, the underworld is mostly far more intriguing than the real Bolsheviks who save Mr West at the climax of the film, showing him such marvels as a Red Army parade and the Shabolovka radio tower, a similar unstable dichotomy between the dissolute and the regimented to that of Meyerhold’s D.E. Yet one of the most intriguing elements of Kuleshov’s work is in the cohesion of the collective, both in their role as Mr West’s antagonists and in their own work. It reminds that there was one element of the popular cinema which, practically without exception, the directors of the avant-garde refused to attempt to subvert or assimilate, but instead disdained, no doubt as one of the elements which could not be ‘useful’: the star system. The actors were instead frequently rather odd looking, their charisma not deriving from their beauty. In the case of Aleksandra Khoklova this met with the active opposition of the nationalised film studios, who effectively banned her from appearing in films due to insufficient pulchritude.

Olga Bulgakova, in an essay on Soviet actresses, wrote that there was a specific ‘Eccentrist woman’ who was usually disdained both by authorities and, apparently, by audiences:

female ‘anti-stars’ of the 1920s were distinguished above all by their unattractiveness [. . .] they were reared on hostility to ‘the star’, ‘the beauty’, ‘the queen of the screen’ [. . .] while everyone was delirious with delight at ‘Greta Garbo’s divine beauty’, a reviewer described Elena Kuzmina (of FEX) as a ‘hiccoughing monster’.52

Bulgakova quotes Eisenstein on this kind of anti-stardom:

Khoklova is no ‘Soviet Pickford’. America is well acquainted with the image of the petty bourgeoisie and the ‘bathing girl’. The very existence of Khoklova destroys this image. Her bared teeth rip up the stencil of the formula ‘women of the screen’, ‘women of the alcove’ – Khoklova is the first Eccentric woman of the screen.53

Bulgakova notes that this was written at the exact point, in 1926, that Kuleshov was told he would only be permitted to make films without Khoklova being allowed a starring role. This side of filmic populism has been described by postmodernist historians in an interestingly dispassionate manner, lest they be accused of criticising authentic popular desire.

Adventures of Ms East

The comedies of Kuleshov’s collaborators (many of whom – Komarov, Barnet, Pudovkin – became directors soon after Mr West), from 1925–27, are more inclined to fulfil Trotsky’s requirements for a specifically Soviet satire.54 Boris Barnet’s The Girl With the Hatbox (1927) contains many anti-NEP jibes, for instance, although used in a measured and decidedly Americanist form. Perhaps more than any other, this film resembles a direct Soviet transposition of one of the gentler American comedies, such as Keaton’s Our Hospitality (1923), with a more realist and slightly more formally experimental bent. The squalor of the period is evoked in the subterfuge and exploitation that the heroine, a shopgirl who lives in the semi-rural outskirts of Moscow, has to undergo at the hands of her boss, who utilises part of her flat, with the constant threat of the sack being held over her. False names, rented spaces, homelessness, marriages of convenience, workplace bullying and the obvious survival and continued power of the bourgeoisie are all treated as objects for mordant comedy, though not quite agitation. Though it in a sense accomplishes the task of making an efficient comedy with Soviet material, its deus ex machina ending, via a lottery ticket, would no doubt have seemed to have dubious political usefulness. Meanwhile, much unlike Barnet’s former partners in the Collective of Failed Actors, its lead actress Anna Sten was conventionally beautiful enough to be picked up and groomed by Samuel Goldwyn in the 1930s.

The Stenberg Brothers’s Poster for The Girl with the Hatbox

Another example of the comedy of NEP comes as one of the many ingredients in Yakov Protazanov’s 1924 film Aelita. Though, directed by a former White émigré from a novel by another former White émigré, it earned the derision of much of the avant-garde, this film still contains significant Constructivist input – from Isaac Rabinovich’s abstract sets to Alexandra Exter’s costume designs, and not excluding Aleksei Fajko and Fyodor Otsep’s Eccentrist, defamiliarising script, constantly frustrating predictable outcomes. Accurately described by Ian Christie as ‘polyphonic’,55 the film combines quasi-Constructivist fantasies of revolution on Mars, grim scenes of immediate post-Civil War privation, and Chaplinesque farce from Igor Ilinsky.

Here, there are Red Army men who, after the failure of the world revolution at least manage to create revolution on Mars, alongside Moscow-dwellers who hold parties where they dress and act as they would have done before the revolution as an escape from Bolshevism. The satire here is surprisingly pointed, given the direction by a returned anti-Soviet émigré: revolution is seen as a necessarily unfinished project, and the tension between squalor and fantasy does not end in a ridicule of the latter. Aelita presents a world as familiar and as jarringly unfamiliar as the films of the avant-garde; the ‘new stupidities’ receive a series of well-aimed blows.56 What is especially notable about Aelita, however, is its link between dreams (and this is literally a dream, if an enormously vivid one) of revolution in outer space and dreams of world revolution – the central figure dreams of the former at least in part as a means of escaping the NEP’s compromises, as a means of replacing the world revolution’s failure to save the Soviet Union from national backwardness. The dreamer is not mocked, however – it is the mundane world around him that is risible and absurd, not the interstellar revolution that accompanies his sleep.

Eisenstein and Alexandrov’s The General Line, a film which we will return to at various points below, and which was partly filmed in 1926, before the decline of Eccentrism, can be seen to have certain features which derive from the collision of the montage of attractions and distinctly Soviet satire. The film was aptly described by the critic Robert Barry as looking like ‘a Keaton film where the machines all work’, and the satire on bureaucracy is dominated by Eccentrist methods of defamiliarisation – stenographers dominated by a huge typing apparatus, the ubiquitous presence of the Lenin cult leading to bureaucrats morphing into their portraits of the sainted leader. These seem closest of all to the ‘new methods’ that the new idiocies of the 1920s’ bureaucratic state capitalism called for, in that they use the very machines and objects of power as comic and belittling. A not dissmilar satire takes place in Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa (1927), this time based on the claustrophobia of Moscow’s urban space and its effects on attempts to conceive of new forms of sexual relation. Shklovsky’s script features two men, both construction workers (one skilled, one unskilled), essentially exchanging between them the house’s housewife, with the usurped ‘man of the house’ simply moving to another part of the tiny basement flat, behind a partition. The woman, however, eventually feels stifled by both men, and finds liberation in a train ride out of the city. In the fact that the two men are erecting new buildings to replace these cramped conditions there could be an open-ended element to this attack on an ad hoc, accidental new space – the promise that it will be only temporary. Something darker is hinted at in the set design by Sergei Yutkevich, a signatory to the Eccentric Manifesto – an assemblage of petit bourgeois kitsch rammed into the tiny space in order to make it ‘cosy’, and where the characters are constantly framed by wallpaper and doilies, in one of the most persuasive of modernist attacks on the old interior. Among the kitschy artefacts is a 1926 calendar, with an image of a Soviet leader for each month; for much of the film, it is the calendar image of Stalin himself which looms over the characters.57

People and objects: Bed and Sofa

Joe is already watching you: Bed and Sofa

Slapstick and Instruction

From these films, it would seem that there was a serious attempt to combine a popular form, avant-garde experiment, social satire and explicit socialist commitment in early Soviet comedy. However, accounts, both contemporary and retrospective, tend to be less sanguine. The most detailed study of the films and directors (or rather, studios and stars) who were actually considered ‘popular’ in the Soviet 1920s is in Denise Youngblood’s Movies for the Masses – Popular Cinema and Soviet Society in the 1920s. This charts the gradual attempts to reduce the dependence on receipts from the screenings of American films and official programmes to reform popular taste. In profiling the ‘Education or Entertainment’ debate during NEP (a period when foreign and especially American imports had an overwhelming dominance over the ‘market’ – she quotes a statistic to the effect that an American film would make a profit of 100 per cent and a Soviet-produced one a loss of 12 per cent), she places the avant-garde on the side of the debate that stands for ‘improving’ cinema, for the ‘dull but worthy’.

Alexei Gan, because of his rages against imported pictures that ‘poisoned the masses’, is quoted in the same breath as Nicholas II, although it is pointed out that ‘unlike Nicholas II, (leftists) did believe that ‘popular’ art (art for the masses) was to be encouraged, albeit via ‘social, cultural and political enlightenment’.58 This is of course the same Alexei Gan whose journal Kino-Fot was a focus for the cult of slapstick, and in the issue which was mentioned earlier in the chapter, produced a particularly impressive celebration of the avant-garde’s cult of Charlot. Similarly, the self-proclaimed ‘Americanitis’ of the FEX and Lev Kuleshov, not to mention Eisenstein, is given fairly cursory mentions. It is surely clear that a critical affection for, and a critical engagement with, American cinema was common to practically all ‘leftist’ directors, with even the irreconcilable opponent of the fiction film, Vertov, owing a debt to the speed of ‘American montage’. Meanwhile, the avant-garde affinities of the work that Youngblood considers a genuine engagement with the tastes of working class cinema-goers, that of Boris Barnet and Friedrich Ermler, has in turn clear affinities with the work of the avant-garde in the attention to montage and making-strange. As counters to the avant-garde, Youngblood reproduces from the fan magazine Soviet Screen; but as well as a love for stars and glamour, these images also show a huge amount of photomontage and Constructivist typography, as well as drawings evoking the Schlemmer-like work of Alexander Deineka – not to mention a sketch of ‘the soul of the American film’ which closely resembles the 1910s ‘American’ drawings of George Grosz.59

What this overlooks is that the avant-garde was both obsessed with popular culture and intent upon changing it. If Chaplin or Griffith could be critically assimilated into their work, other elements, such as the happy ending, the star system (which, as we have seen, was deeply misogynist in its treatments of unconventional actresses like Khoklova or Kuzmina) and anything that signified ‘escapism’ were to be expunged. The argument that this was unpopular with audiences also seems inconclusive. Pudovkin’s Mother (1926), for instance, was a genuine popular ‘hit’, while other vanguard works such as FEX’s New Babylon (1929) or Eisenstein’s October (1928) were clearly box office failures – although this may be connected with the increasing official hostility to ‘formalism’ from 1927 onwards. The argument against the cinematic avant-garde is a postmodernist one: the problem with Marxists and Modernists is that they won’t accept that popular desire is, and always will be, for what Youngblood calls ‘those pictures which appeal to the lowest common denominator (through a combination of action and sentiment)’, and while an attempt to create a collision of agitation, defamilarisation and popular art might result in Great Art which can be safely contemplated in MOMA, it will always be unpopular with the audience for whom it was intended, who merely want a bit of escapism after work. The assumption is that this would be as true in the ‘new society’ as it was in the old; ‘choice’, meanwhile, should be paramount, so any attempts at education should, presumably, be kept to the schools. What the Red Clowns promised was that this fixed perspective could be broken apart.