Despite Hollowell’s victory in the Coke case, which opened doors to blacks at facilities in the Atlanta airport terminal, many other doors in Georgia remained shut—especially the doors to all-white schools. In 1958, four years after the Brown decision, Jesse Hill and other black civic leaders renewed their challenge to racial segregation in public schools in Georgia. They chose Donald Hollowell as their chief counsel. Hollowell’s legal groundwork in the Ward and GSCB cases would prove particularly valuable in countering the legal maneuvers by state officials intent on maintaining segregation in education in Georgia.

Hollowell, who remained a key member of the Atlanta NAACP, was a leader among the community activists who decided it was time to revive their efforts in higher education.1 His law firm had continued to focus on civil rights cases, and his direct connections to Thurgood Marshall and the LDF were huge assets for the activists who wanted to challenge the segregationist system. Prompted by the Brown decision, the LDF had begun to receive major gifts from foundations and corporations, including Rockefeller, Ford, and Carnegie. Marshall directed the support to finance legal cases aimed at bringing an end to segregation.2

The LDF paid expenses and court costs for the cases in which it was involved, including expenses for air travel, lodging, and meals. Because most of Hollowell’s travel was in state and Jim Crow restrictions prohibited him from staying in hotels during the 1950s and early 1960s, he did not incur expenses for lodging or air travel, other than the cost of trips to New York to confer with LDF attorneys. During in-state overnight travel, Hollowell often stayed with friends and supporters. In the mid-1960s, the LDF began to offer allowances of salaries in its monthly remittance of expenses and court costs. However, the fees were not large, especially in light of the extensive workload and long hours associated with such cases.3

Additionally, in some cases Hollowell was called on to do legal work for the NAACP, which was even more strapped for cash than the LDF. For example, in regard to a 1964 hearing in the case of Preston Cobb, a major criminal case that required Hollowell to travel to New Orleans, Robert Carter wrote to Hollowell: “I am writing you about the scheduled argument in Cobb set for October 9th. . . . I must point out that the Association is at present in what I hope is a temporary financial crisis. I cannot assure you that we would be able to pay you for arguing the case or when, and I am reasonably certain that we could only pay $100 over and above expenses. How soon we would be able to do even that, I can’t say”4 Despite the uncertainty of when or even whether he would be paid, Hollowell responded that he would travel to New Orleans to argue the case. Such instances illustrate Hollowell’s generosity with his time and expertise despite his expectation of receiving little or no compensation.

Although Hollowell worked closely with Marshall and the LDF, local lawyers made decisions about which cases to pursue and to appeal. Howard Moore recalled that the LDF never dissented from attorneys’ decisions at the local or state level, other than dissuading them from involvement in cases involving labor organizations, because labor entities such as the AFL-CIO were major supporters of the LDF. Moore also noted, “If any Communists were involved, we were to distance ourselves from them.”5 Segregationists who labeled civil rights advocates as Communists did so to discourage support for civil rights and enrage opponents of the movement. The Communist label would thus have severely impacted LDF financial support.6 With these caveats, however, Hollowell and his law partners were free to actively pursue cases to eliminate state-sanctioned racial injustice.

Emboldened by the federal injunction against racial discrimination at the GSCB, Hollowell was determined to win a landmark court order for the admission of black students to an all-white college. Meanwhile, Georgians had chosen Ernest Vandiver—a staunch segregationist and a protégé of Herman Talmadge—as their new governor. Vandiver was a formidable opponent whom Hollowell would face many times in the struggle to desegregate Georgia’s schools. Vandiver later explained his segregationist stance of the time in a legal context: “My campaign platform at that time was to preserve the county unit system, to preserve segregation, which we had been brought up with all our lives, to give the legislature independence, and not to raise taxes. . . . When you are inaugurated, you swear to uphold the Georgia laws—whether [or not] it is the law of the United States. Georgia laws at that time—you know what it was. They [the schools] should be closed rather than integrated.”7

The school desegregation campaign mounted by black civic leaders under Hollowell’s legal guidance targeted the entire University System of Georgia, which included sixteen institutions for “white students only.”8 In addition to the all-white institutions, Georgia had three historically “Negro institutions”: Fort Valley State College, Savannah State College, and Albany State College, all founded in the late 1800s and offering a liberal arts curriculum. The funding and resources provided to these black institutions by the state’s regents from taxpayer revenues were minuscule compared to those provided to the all-white institutions. There were no graduate or professional programs for blacks within the state university system; for that matter, graduate and professional programs for blacks in the southern states were virtually nonexistent.9

In addition to Hollowell and Hill, the community activists who sought to break the color barrier in Georgia’s colleges and universities included Rev. Dr. Samuel Williams, Morehouse College professor, president of the Atlanta Branch of the NAACP, and pastor of Friendship Baptist Church; Atlanta University School of Social Work dean Whitney Young; and M. Carl Holman, who was then an English professor at Clark College.10 Holman later became editor of the Atlanta Inquirer, the radical weekly founded during the Atlanta sit-ins to rival the more moderate Atlanta Daily World, which curtailed its coverage of some militant events due to its white advertising base.11 Most of the activists participating in this effort to desegregate colleges and universities came from black institutions that were not as subject to intimidation or control by the white power structure. Hill used his independence and resources from the black-owned Atlanta Life Insurance Company to become the chief catalyst in many of Georgia’s civil rights battles.

The most difficult challenge to Georgia’s rigidly segregated colleges and universities, and the most celebrated victory, would be the desegregation of the state’s flagship university. The activists were keenly aware of the impact of a victory that would result in the desegregation of the flagship school. Jesse Hill observed, “We said to ourselves, if we could crack the University of Georgia, then everything would fall down; they would fall like dominos. And so we literally put the Georgia State case aside and decided to concentrate on the University of Georgia”12

In the grand tradition of Atlanta’s black middle class, the community activists selected two candidates with impeccable and wholesome backgrounds. After the attacks on the characters of the GSCB applicants, which dampened the court victory, Hollowell was meticulous in his efforts to select applicants whose backgrounds would be difficult to besmirch, given the all but certain attack that would come from state and university officials. In selecting the students, the leaders undertook a rigorous screening process that included a series of interviews with the candidates and their parents. Hill recalled: “We did our homework and we carefully selected students who could not be criticized. . . . In other situations where we’ve tried to desegregate venues, we have not been quite as careful and selective. But in this case, it was airtight. We talked to those students for weeks and weeks before they completed the applications.”13

Hollowell, Hill, and the other activists selected Hamilton Holmes, the son of a middle-class family long active in the civil rights movement, and Charlayne Hunter, the daughter of an army chaplain and a career woman. Both had high aspirations. Holmes wanted to become a doctor like his grandfather, while Hunter was interested in journalism. Moreover, and fittingly, Holmes was descended from a long line of “race men” committed to racial justice. Alfred (“Tup”) Holmes (Holmes’s father), Dr. Hamilton Mayo Holmes (Holmes’s grandfather), Oliver Wendell Holmes (Holmes’s uncle), and family friend Charles Bell had challenged the segregated golf courses in Atlanta in 1955. This bold family team of civil rights activists sued the city in federal court in a case that resulted in the desegregation of Atlanta’s golf courses in 1956, the first publicly desegregated facilities in the city.14 In an interview, Isabella Holmes, Holmes’s mother, declared that not only was her son ready for the challenge, but that his father and grandfather strongly influenced him to continue the family’s legacy in academic excellence and race uplift.15

Hunter’s parents, Charles S. H. Hunter Jr. and Althea Hunter, were also supportive of their daughter’s choice. Although they had not been leaders in the Atlanta civil rights movement, they had in their own way grappled with the system of segregation. Her father joined the segregated military early in World War II as an army chaplain and ministered to soldiers who fought for America on faraway battlefields and died without being honored as first-class citizens. Hunter remembers that her father’s sermons always focused on human dignity and human rights.16 Though her father was away in the military during much of the time she struggled to enter the University of Georgia, her mother stood firm and provided strong family support. Both Holmes and Hunter had exemplary high school records and were the progeny of the city’s black elite—the kind of students coveted by the nation’s black colleges.17

Despite their impeccable records, Holmes and Hunter were African Americans in a state bent on maintaining segregation, especially in schools. It was an arduous process even to secure admissions applications. Hill made several unsuccessful attempts to obtain applications by making requests to admissions officials. While the university did not allow African Americans as students or faculty, blacks made up the majority of the janitors at the institution. Determined to overcome the stalling tactics and secure applications for Holmes and Hunter, in an unconventional move, Hill convinced one of the janitors in the admissions office to surreptitiously secure applications.18

In July 1959, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes were finally able to apply for admission to UGA. As expected, the university summarily rejected their applications on transparently fraudulent grounds. Holmes recalled:

We were told at that time Georgia had a requirement that all freshmen had to live on campus, male and female. Females had to live on campus for four years, males just for the freshman year—then they could move, and move anywhere they wanted to. They told us that because of no dormitory space—they did not say because we were black, they said because there was no dormitory space—they could not accept us.19

That disingenuous response signaled the start of a long legal process that would eventually end 175 years of segregation at the University of Georgia. Hollowell had been down this road ten years earlier in the Horace Ward case. This time he was determined to finish the fight. And this time he had at his side not only the veteran Constance Baker Motley but also two bright new recruits: his young law clerk Vernon Jordan and his former client and new law partner, Horace T. Ward. Jordan remembered:

I started working with Hollowell the Monday after I graduated from law school. And that first day we were in Atlanta Municipal Court getting demonstrators out of jail because the civil rights movement was hot. . . . I was the first young law school graduate that Hollowell brought to his office. Horace Ward came in September, and we had a very good time. I carried Hollowell’s briefcase, I drove his car, did his research, I studied under him, I was his law clerk, I was his mentee, and we had lots of cases—too numerous to mention—having to do with violations of civil rights and asserting equal opportunity rights for plaintiffs. The most significant by far was the University of Georgia case.20

Jordan and Ward were crucial in helping Hollowell meet the increasing demands on his practice. By 1960, Hollowell was severely overburdened with civil rights cases that ranged from his representation of criminal defendants to public accommodations cases such as the Coke case to the renewed challenge to desegregate UGA. Due to the volume of demands for his counsel as chairman of Georgia’s NAACP Legal Redress Committee and the routine cases of his firm, he often simply did not have the time to follow up on important cases.

For example, in 1964, Augusta branch NAACP president Rev. C. S. Hamilton complained to NAACP executive Roy Wilkins after parents of prospective plaintiffs waited more than a year for Hollowell and local attorneys in Augusta to file a school desegregation case. In a May 21, 1964, letter to Wilkins, Hamilton stated:

We were told by our local attorneys, Mr. Ruffin and Mr. Watkins and Mr. Hollowell of Atlanta, that the school case would be filed in April of last year but to date nothing has been done.

I am aware that all of us are busy; but when a community is organized and ready to move, then the attorneys do not follow through with a case like this, it handicaps us as leaders of the NAACP in the local community.

After talking with the attorneys, the parents were told the case would be filed within thirty days but a whole year has passed since then.21

A few months later, Hamilton complained to NAACP’S Southeast director Ruby Hurley, “I hate to bring a complaint every time I write but our chief attorney Donald L. Hollowell was supposed to have sent material to the local school board after the hearing in Brunswick on the 24th of August. . . . We look for Judge Scarlett to stall but not Attorney Hollowell. If he does not have time to handle the case why start it and drag it out as he has?”22

Hollowell’s lack of a timely response to Hamilton was likely due to the overwhelming demands on Hollowell’s time. In a December 29, 1965, memorandum to Jack Greenberg, Hollowell and Howard Moore summarized the civil rights cases on which they were working cooperatively with the LDF in December 1965. Not including school desegregation cases, a panoply of cases on appeal, and numerous cases in which the LDF was not involved, Hollowell and Moore were handling more than twenty-five cases with the LDF. Examples of cases throughout the state included the following:

• two cases in Crawfordville, Georgia, involving petitioners arrested for picketing for equal rights, and a case involving Clifford Cooper Jr., charged with reckless driving resulting from his effort to elude a hostile white mob

• a case in Columbus, Georgia, involving blacks arrested for picketing a place of public accommodation without a permit

• a case in Dublin, Georgia, in which fifty-four blacks were arrested for picketing a segregated filling station in the black community

• a case filed on behalf of several young blacks in Savannah, Georgia, under the Fair Labor Standards Act for unpaid wages and overtime compensation

• a case filed to enjoin segregation in drive-in restaurants in Savannah after Dick Gregory led a group of young blacks in sit-in demonstrations

• a case against Mardon Walker related to her arrest and jailing in connection with a sit-in at an Atlanta restaurant

• a case involving Preston Cobb Jr., a fifteen-year-old black youth convicted and sentenced to death by electrocution23

On the civil rights cases that Hollowell litigated across the state, it was common for him to work sixteen-hour days over long periods of time. Besides his extended working hours on civil rights lawsuits such as the Holmes case, he was forced to practice a wide spectrum of law to help pay the bills. Howard Moore, whom Hollowell recruited to his firm in 1962, remembered: “The areas of law which he mastered were amazing. Not only could he do criminal law, but he could do civil law. He could do contracts; he could do wills; he could do probate; he could do family law. And not only did he do trial work, he did appellate work, and he did transactional work.”24

Although Hollowell had won several civil rights cases, financial compensation for civil rights work was minimal during this era, and Hollowell often used his own money to pay clients’ legal expenses, which clients were unable to reimburse. Hollowell was able to take civil rights cases with no or little remuneration because he and his law partners financed the law practice from fees earned from work in other areas. His partners therefore not only played an important role in the firm’s civil rights litigation but also performed the routine legal work—such as family law, wills and divorces, probates and estates, contracts, personal injury work, and representation of black businesses—that provided vital income to the practice.25

Atlanta had a thriving black business community anchored on historic Auburn Avenue, and there was a great deal of activity in the area of small business transactions.26 Hollowell’s clients during the formative years of his practice included James and Robert Paschal, owners of a sandwich shop that opened in 1947. In addition to representing the Paschal brothers in business matters such as the acquisition of property, he handled more mundane day-to-day legal matters as well. For example, among hundreds of documents from Hollowell’s office revealing his extensive work unrelated to civil rights is a copy of an executed agreement, prepared by Hollowell, releasing the Paschal brothers from liability in connection with a leather coat stolen from the coat rack at Paschal’s restaurant.27 The Paschal brothers later developed the world-renowned Paschal’s Motor Hotel and Restaurant, which became the unofficial center of operations for the nation’s civil rights leadership.28

As Atlanta’s demographic patterns changed and blacks were afforded suburban real estate opportunities, Hollowell’s firm also provided legal assistance. After Hollowell and his wife purchased a home in the Collier Heights subdivision, one of the first suburban developments in the nation to be built by blacks for blacks, Hollowell handled much of the legal work for many other Collier Heights purchases.29 Howard Moore remembered that fees for the legal assistance provided by the firm were not large, but they were steady, and the work provided an excellent source of referrals in other practice areas.30

Over the long course of the new UGA case, Hollowell and his team would encounter a host of familiar stalling tactics and maneuvers by state officials. Holmes and Hunter filed a series of appeals to university and regents officials who had repeatedly rejected their applications. Meanwhile, to avoid losing any time from college, Holmes attended Morehouse College in Atlanta, and Hunter attended Wayne State University in Detroit.31 This proved to be a mixed blessing, for after the completion of their freshman years of college the prospect of entering the University of Georgia had become far less appealing for both students. Holmes had settled into the elite Morehouse College atmosphere, excelling in his studies and joining the prestigious Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, and Hunter had become a popular student at Wayne State and a member of the prominent black sorority Delta Sigma Theta.

Nonetheless, Holmes considered the University of Georgia’s superior science facilities ideal for his premedicine interests, and UGA’S premier journalism school still attracted Hunter. The combination of their interests and the strong influence of Hollowell and other community activists led them to again pursue admission to UGA. During the summer of 1960, Holmes and Hunter filed applications to enter the university for fall quarter 1960 as transfer students.

Once again admissions director Walter N. Danner refused to admit them, and they appealed to the regents. Frustrated with administrative minutiae and delays imposed by the regents, on September 2, 1960, on behalf of Hunter and Holmes, Hollowell filed for an injunction before federal judge William A. Bootle in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Georgia to prohibit the university from denying them admission due to their race. The petition also asked the court to enjoin Danner from refusing to consider the applications of black residents of Georgia for admission to the university. Although Hollowell served as chief counsel, helped organize community activists to support the case, and selected Holmes and Hunter as plaintiffs, the LDF provided expert assistance. LDF attorneys Thurgood Marshall, Derrick Bell, and Constance Baker Motley were among those who filed the injunction. Bootle refused to issue the injunction, ruling that Holmes and Hunter had not exhausted administrative remedies. Instead, he ordered the regents to rule immediately on whether the two applicants could proceed with personal interviews, invoking the loosely enforced admissions requirement created after Horace Ward tried to enter the university and reserved for use by university officials to exclude blacks.

In response to Bootle’s order, Danner scheduled interviews with Holmes and Hunter. Holmes’s interview occurred on November 18, 1960. He described his interview as a calculated attempt to prove he was not qualified for admission: “The interview was obviously an effort to trap me and was obviously an effort to show that I was not qualified for admission to the university. The questions that they asked me were very personal, very negative; they were trying to show that I was not a very desirable person. That my family was not desirable. That my high school was a lousy high school. There was nothing positive about my interview. I don’t recall if they ever asked me what kind of student I was”32

It was a favorite strategy of southern opposition lawyers to attempt to discredit plaintiffs who legally challenged the segregationist system. Since the Brown decision had ruled racial segregation unconstitutional, proponents would simply dream up other reasons to exclude black applicants. Assailing the character of black applicants, often with fictitious information, was a popular legal shenanigan. Constance Baker Motley noted: “Whenever we filed one of these suits, what they wanted to do, of course, was disqualify the applicant on some ground other than race. So whenever we filed one of these suits, what they would do was investigate the plaintiff—whoever that plaintiff was, male or female—from the day they were born.”33

Hunter’s interview was a somewhat kinder, gentler version of administrative Jim Crow, but the outcome was the same: admission denied. While admissions director Danner informed Holmes and Hunter that they had been rejected because of insufficient dormitory space, he also told Holmes that he did not qualify as a “suitable applicant to the University of Georgia” on the basis of his personal interview.34 During the interview, Holmes had responded “no” to the question of whether he had ever been arrested. In an effort to assail Holmes’s character, admissions officials asserted that Holmes had lied, contending that a previous speeding violation they discovered constituted an arrest.35 Notably, the law school dean, J. Alton Hosch, had given virtually the same reasons for rejecting Horace Ward—evasiveness and contradictory statements in his responses during his personal interview.

Exasperated with the obstructionist tactics, chief counsel Hollowell led his team in preparing for the trial. With the help of the LDF, they conducted meticulous research on thousands of university admissions records. Vernon Jordan, a junior member of the team, discovered the smoking gun—the key piece of evidence that irrefutably revealed the duplicity of university officials. Jordan recalled:

I was lucky enough to be the one to find the record of the woman who lived in Marietta, Georgia, Cobb County, who was a transfer student who had been admitted to the university subsequent to Charlayne’s application, and Charlayne was being denied on the basis that a junior could not transfer—“some Dannerism,” I would call it. This evidence convinced us that we had a case.36

The evidence Jordan found was especially pertinent because the student admitted after Hunter had an academic profile almost identical to Hunter’s—she was both a transfer student and a journalism major.37 Hollowell now had the ammunition he needed to make his case; he argued before Judge Bootle that Holmes and Hunter were denied admission solely on the basis of their race.

On November 18, 1960, Bootle scheduled a courtroom trial, which was held in Athens, Georgia, on December 13–17, 1960.38 In a series of questions during the trial that convincingly made the case for admitting Holmes and Hunter, Hollowell introduced the evidence that Jordan had discovered. The evidence revealed that Bebe Brumby, daughter of the late Otis A. Brumby, member of the General Assembly and owner of two Georgia newspapers, had been admitted to the university for winter quarter 1961, although she had applied after Hunter and Holmes submitted their applications. Brumby was also a relative of United States senator Richard Russell.

The fact that both Brumby and Hunter aspired to be journalists and had applied as transfer students made the disparate treatment even more apparent. It also made the acceptance of Brumby and rejection of Hunter due to limited dormitory facilities indefensible. Hollowell’s questioning led to revelations that Brumby actually had been courted for admission, in stark contrast to the flat-out rejection of Holmes and Hunter.39 In a crucial courtroom exchange between Motley and admissions counselor Paul Kea, Motley made it clear that it was not Brumby’s exceptional academic record that justified her special treatment:

MOTLEY: Would you look at that transcript and tell me what kind of student she was, since you evaluate transcripts of transfer students? Was she an “A” student, a brilliant student?

KEA: Well, I would say that of course she is not an “A” student because there is not an “A” on the transcript.

MOTLEY: Do you see any “Bs” on there?

KEA: Yes. There are two “Bs,” the rest are “Cs”40

Hollowell systematically attacked the spurious tactics and double standards that university officials had used to block the admission of his clients. In a brilliant tactical move during the trial, he educed testimony from UGA president Aderhold that Horace Ward, whom Aderhold and law school dean Hosch had contended did not have the type of mind to study law, had graduated from the prestigious Northwestern University School of Law and was in the courtroom as one of the lawyers on his team. Hollowell then sought to elicit information from Aderhold to emphasize that Ward had entered a law school at least equal to the school that had rejected him.

The defendants’ attorney, B. D. Murphy, strongly objected to Hollowell’s line of questioning. Murphy asserted that he could not see any possible relevancy of the reputation of Northwestern University’s law school. Hollowell responded: “I would submit, your honor, that the witness has testified that under the records here that this young man . . . was denied, among other things relative to qualifications, and that he now further testifies that he understands that he [Ward] is a lawyer who is a part of this case. I felt that it would be relevant to establish that the school at which he attended was at least on a par with the school at which he had previously applied.”41

Bootle overruled Murphy’s objection, and Hollowell continued to question Aderhold, contrasting Ward’s acceptance at Northwestern University with his rejection by the University of Georgia. In another strategic move, Hollowell had Ward conduct the direct examination of Holmes on the witness stand.42 Hollowell noted that Ward brought with him a special passion to see the Holmes case achieve what his own legal case had not been able to accomplish. Hollowell said it made him feel very good to have Ward work with him on the case against UGA because justice had not been served by the outcome of the Ward case. Hollowell concluded that one of the most interesting things to develop out of the Ward case was the fact that Ward had graduated from Northwestern University School of Law and was able to be a part of the Holmes v. Danner legal team.43 Vernon Jordan summed up the irony, noting, “There’s a lot of poetic justice there, that Horace could be denied himself and come back and be counsel to Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes—as my mother would say, ‘The Lord works in mysterious ways.’”44

In yet another move reminiscent of the Ward case, Murphy sought to show that Holmes did not have a serious interest in admission to the University of Georgia but was pursuing admission at the behest of the NAACP. Murphy relentlessly questioned Holmes about who had advised him regarding admission to UGA and who had retained Hollowell to represent him, in his effort to show that Holmes was a pawn of the NAACP. A seemingly exasperated Hollowell objected to the line of questioning:

HOLLOWELL: May it please the Court, I submit that this is cross-examination and that the counselor has broad discretion and he can sift as fine as a flour sifter, but I submit that there should be some relevancy to the matter at hand, and I just can’t see any relevancy to this type of questioning, as to what specific individuals have discussed with him the matter of going to the University of Georgia, and I object to it on the basis that it is irrelevant.45

Although Bootle allowed Murphy to continue his line of questioning trying to show that Holmes was not a bona fide candidate, “Bootle . . . appeared to share Hollowell’s sentiment concerning the irrelevancy.”46 In the following telling exchange, which followed Hollowell’s repeated objections, even Murphy made a statement that impugned the relevancy of his own questions to the central issue of the trial:

HOLLOWELL: I submit, Your Honor, that he [Holmes] has not said, and he has said four times now, because the last time I objected it was the third time, that he did not retain the counsel, that his father retained the counsel, and that he didn’t know when, exactly, his father retained the counsel. Certainly there is no relevancy.

THE COURT: Well, I don’t want to curtail counsel in anything that you tell me in your place that you bona fide think is relevant to this inquiry. Do you bona fide think it is relevant?

MURPHY: I think it is relevant. I don’t think it is relevant to whether or not he ought to be admitted to the University of Georgia, but—

THE COURT: Well, that’s the only thing we are trying, isn’t it?

(LAUGHTER)

THE MARSHALL: Order in court. If you are going to remain in the courtroom you will have to be quiet. Otherwise, we’ll have to clear the room.47

Hollowell’s strategy to win the admission of Holmes and Hunter included an effort to show how absurd it was that the tax-supported university accepted students from around the globe but refused to accept any of its native citizens who were black. Hollowell called a secretary from the university housing office to the stand:

HOLLOWELL: Miss Costa, might you indicate some of the different races or nationalities that are presently housed at the University in the dormitories?

COSTA: We have Japanese students, we have Chinese, we have students from India, we have students from Holland, students from France . . .

HOLLOWELL: Do you have any students of Negroid extraction there to your knowledge?

COSTA: Not to my knowledge, no.48

Hollowell’s strategy and sheer courtroom presence throughout the trial dazzled his young clients, leaving a lasting impression. Holmes said, “When he was walking around he’d raise his hand up and point his finger. He was always slow and deliberate. I mean he was just fantastic . . . one of the most impressive men I had ever seen.”49 Andrew Young observed:

Don Hollowell was a gentleman and a master and more like a Shakespearean actor in the courtroom than the typical lawyers we saw at that time. Even Thurgood Marshall could be kind of folksy, but Don Hollowell and Constance Motley were the Shakespeareans, and it would always impress me whenever I was in a courtroom, not only would they quote the cases, but when the judges would send the law clerks to pick up the volume to check the case, they would say, “You will find that on page 365, Your Honor.” They were right on the case and you just felt proud sitting in the courtroom watching them handle things.50

An able opponent in the courtroom battle was assistant state attorney general E. Freeman Leverett, a formidable attorney who specialized in defending the state against civil rights cases in the 1960s. Yet as Leverett would recall in later years, Hollowell was even more formidable: “Don Hollowell was one of the best trial lawyers I’ve come up against and probably did most of the work. He did an excellent job of discovery and getting the records and showing that there had been a disparity in the way the white applicants were dealt with by university officials and the way the black applicants were dealt with.”51 Hollowell was also the first black lawyer to try a case before Judge Bootle, who was impressed by Hollowell’s legal skill. In an interview, Bootle vividly recalled that Hollowell was a “good trial lawyer” with excellent courtroom presence.52

On January 6, 1961, Bootle delivered his historic ruling, finding for the plaintiffs. In light of the huge disparities that Hollowell and Motley had exposed in the treatment of Holmes’s and Hunter’s applications as compared to those of the white applicants, Bootle ruled that the black plaintiffs were denied admission to the state university solely because of their race. Bootle opined that “Had . . . plaintiffs been white applicants to the University of Georgia both would have been admitted to the university not later than the beginning of the fall quarter, 1960.”53

In direct opposition to testimony from Aderhold, who denied any knowledge of a university “policy to exclude students on account of their race or color,” Bootle found that there was indeed a tacit policy to exclude blacks from admission to the university on account of their race and color.54 In perhaps the most telling example of officials’ untruthfulness related to their contention that Holmes and Hunter were rejected due to limited dormitory space, Bootle opined that the true reason behind the “limited facilities” claim was best expressed in a handwritten letter from Chancellor Caldwell to President Aderhold dated June 15, 1960. Caldwell stated in the letter that it was his understanding that all dormitories were filled and that Aderhold was “relying on this to bar the admission of a Negro girl from Atlanta”55

With a mountain of prima facie evidence revealing the defendants’ true motive—to preserve the segregationist system—the fair-minded Judge Bootle ordered the immediate enrollment of the two plaintiffs. Bootle’s decision was a major victory for Hollowell, his clients, and the cause of equal justice under the law. It would not, however, bring an immediate end to nearly two centuries of segregation at the university. Before that victory could be achieved, there would be a desperate, last-minute legal skirmish accompanied by student unrest and even violence.

To forestall the desegregation of the university, at Governor Vandiver’s request the state immediately appealed Bootle’s enrollment order.56 Bootle, with a volte-face typical of the legal quirks in this case, obligingly granted a stay of his own order.57 Hollowell and Motley then countered with their own appeal to Elbert Tuttle, Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals judge in Atlanta, for reinstatement of Bootle’s injunction against the university. Tuttle, a progressive federal judge unfettered by the entrenched racial prejudice in the Deep South, was unafraid to do his duty at a time when racial justice for blacks was very unpopular.58 Judge Tuttle therefore summarily upheld Bootle’s original decision, declaring that the Supreme Court had held many times that institutions of higher education could not exclude persons based on their race or color. Accordingly, on January 9, 1961, the same day Bootle issued a stay of his order, Tuttle ordered the immediate enrollment of Holmes and Hunter.59

Later that eventful day, with a howling mob in the background, Holmes and Hunter, accompanied by Jordan, Ward, Holmes’s father, and Hunter’s mother, successfully completed the registration process.60 The next day the state, desperate to preserve the segregated system, appealed to the United States Supreme Court. Eugene Cook, Georgia’s attorney general, hand-delivered the seven-page appeal to Edmund Cullinan, the deputy clerk of the court, with instructions that it be delivered to Justice Hugo Black, the supervising judge of the Fifth Circuit. Justice Black, instead of acting unilaterally, presented the petition to all of his colleagues who were in session that day. With unprecedented swiftness, all nine justices affirmed the order to enroll Holmes and Hunter immediately.

As news of the Supreme Court decision spread in Atlanta, friends and associates of Hollowell converged on the Hollowells’ modest home in the Collier Heights subdivision in Atlanta to celebrate the victory. Vernon Jordan and his wife, Shirley, ushered the group to Hollowell’s den, where they led the celebrants in dancing the “Mashed Potato.” The celebrants shouted a joyful chant that summed up the appeals process that ended in success for the Hollowell legal team—“From Bootle to Tuttle to Black and Back.”61

Meanwhile, Governor Ernest Vandiver reentered the fray. Standing on his campaign promise of “No, not one!” he ordered all university funds to be cut off in accordance with the package of segregationist laws devised shortly after Ward’s application.62 The Georgia Appropriations Act required the withholding of funds in the event that a black student entered an all-white college.63 Vandiver contended that this was one weapon the state had in reserve to sustain segregation in the event of a court order.64

In yet another countermove, Hollowell’s team filed for a temporary restraining order of Vandiver’s executive order to close the schools. Judge Bootle was not impressed with Vandiver’s order and ruled to invalidate the package of patently unconstitutional segregationist laws set up to prevent Ward and other blacks from entering white schools.65 Bootle held that university officials were not “free to order the admission of plaintiffs when, apparently, the result of such admission under the General Appropriations Act of 1956 would be to cut off the appropriation of funds for the University of Georgia.”66 Even more than forty years later, Bootle retained some degree of annoyance at Vandiver’s attempt to circumvent his ruling, saying, “He was going to close the university to keep from complying with my order. That wouldn’t do! I didn’t hesitate one second to enjoin him as soon as the motion for an injunction was made by counsel.”67

Within five days, some of the dust had already settled. Holmes and Hunter showed up for their first classes on the morning of January 11, 1961. Not surprisingly, however, the battle was not over. After the relative decorum of the courtroom, Holmes and Hunter encountered open hostility and violent behavior on the UGA campus, which erupted into a riot that night. Rioters converged on Hunter’s dormitory with heightened tensions following UGA’S basketball game loss to arch rival Georgia Tech. Revealing his intolerance with the admission of Holmes and Hunter and frustration with the loss to Georgia Tech, one student remarked, “We got beat by Georgia Tech and we got beat by the niggers”68 Rocks and other missiles were thrown, fires were ignited, windows were broken, and the crowd chanted racial insults.

Shortly after the melee at Hunter’s dormitory, Hollowell pleaded for reason during a press conference:

As to whether or not we’ve asked for any protection by the law enforcement authorities, we have not as such. I think the city police there and such others that are deemed necessary by our justice department or state police authorities would be certainly capable of handling this situation.

I would like to think the people at the university and around the university are sufficiently fair-minded, and they would want to see any Georgia citizen get the best education possible at the facilities that are provided by the state.69

Vandiver refused the university’s request to send in state troopers, but the indomitable dean of students William Tate and several faculty members helped calm the crowd outside Hunter’s dormitory on the evening of January 11. Tate, a stickler for law and order, put aside his segregationist views to protect Holmes and Hunter.70 Hunter observed that Tate stood like a wall against the rioters.71 With the help of fire hoses and tear gas, Athens police and fire officials eventually dispersed the mob of two thousand.

Concerned about Holmes’s safety in a campus dormitory, Hollowell, Holmes’s father, and the group of Atlanta community activists had found refuge for him in the home of Ruth Moon Killian and her two sons, Alfred and Archibald. On the evening of the riot outside Hunter’s dormitory room, Klan members, determined to maintain the segregationist order, threatened to burn a cross outside the Killian home. However, in anticipation of possible mob violence at their home, the Killian household had become an armed base camp. Korean War veteran Archibald Killian recalled: “We had between twenty and thirty black Athenians, with about thirty shotguns, with about thirty cases of shotgun shells, and we were ready to do whatever, Malcolm X, by whatever means necessary. I told them, if you burn a cross at my house, you will not have to ask who came. All you gotta do is turn them over in the morning, pull that sheet off, and you will know because we are going to stand up!”72

The Klan, whose modus operandi relied on fear, retreated from the well-armed Killian household and did not burn a cross.73 In addition to the meticulous work that led to the legal victory, Hollowell and the team of community activists had also carefully planned for Holmes’s personal safety, selecting a family whose courageous actions repelled the Klan and protected Holmes from injury.

Although no serious injury occurred on campus or at the Killian household, the potential for bloodshed lurked in the shadows. Athens police arrested eight Klansmen on campus on charges of disorderly conduct and carrying a deadly weapon to a public gathering. Even more disturbing, police found in the men’s vehicle one .45-, two .22-, and three .38-caliber loaded guns and two belts of ammunition.74 With the help of Dean Tate on campus and the band of black Athenians at the Killian home, both Holmes and Hunter survived the danger without any physical harm. Ironically, however, Holmes and Hunter were forced to return to Atlanta after university officials suspended them from classes, citing concerns about their personal safety, while most of the rioters stayed in school.

Concerned about his clients’ safety even in Atlanta, Hollowell asked Atlanta police chief Herbert Jenkins to provide surveillance at their homes. Louise Hollowell, who had taken a few threatening phone calls, was concerned for her own and her husband’s safety and reminded Hollowell that they might also be at risk. Although Hollowell acknowledged that it had not occurred to him that he and his wife could be in danger, because of his frequent absences from home due to his work, he asked Jenkins to provide surveillance at their home as well.75 Hollowell regularly traveled back roads in Georgia to represent unpopular clients and reasoned that he was far more in harm’s way during these ventures than at his home. Reflecting in later years on the possible danger, he said, “I always figured that if somebody wanted to get me, they would.”76 Although he kept a handgun and a shotgun in his home, he never carried a weapon.

After Holmes and Hunter were suspended, Hollowell’s team returned to the courtroom prepared for battle, but this time the fight was all but won. Judge Bootle ordered the suspensions lifted on January 16, enabling Holmes and Hunter to return to class. Bootle made it clear that he would call on the president for federal troops if state officials would not maintain order. He declared that the lawful orders of the court could not be “frustrated by violence and disorder.”77

Hardened segregationists openly defied the court order, and even some state officials continued to urge noncompliance with Bootle’s order.78 The widespread resistance to the ruling included animosity in Bootle’s own hometown of Macon, Georgia. Bootle’s order reenergized the Klan in Macon. One hundred Klansmen burned a cross on Columbus Road in Macon, and Imperial Wizard Lee Davidson denounced Bootle’s ruling, insisting, “It would be better to close the university” rather than allow it to be integrated. Davidson declared that white people must unite “if racial segregation in the South [was] to survive.”79

Klan-affiliated women from Macon protested at the state capitol, and riotous students hanged Bootle, Holmes, and Hunter in effigy on the UGA campus. Peter Zack Geer, Vandiver’s executive assistant, actually praised the rancor, saying, “The students at the university have demonstrated that Georgia youth are possessed with the character and courage not to submit to dictatorship and tyranny.”80 Segregationist sentiments prevailed among the majority of whites in Georgia, and Bootle’s hometown was no exception.

In an interview, Bootle acknowledged that this environment was part of his own upbringing and culture; he reluctantly revealed that even his own father had tried to persuade him not to render the decision that resulted in the desegregation of the university. Modestly disclaiming his own role, this champion of social justice said: “We were born with it [segregation]. That was a part of our culture. But I wasn’t wedded to it; I was wedded to justice. . . . [The desegregation of the University of Georgia] just happened to happen under my watch. I don’t deserve any credit, don’t seek any. I just did what any honest, self-respecting judge would have done.”81 Bootle noted that although he had grown up in a segregationist environment, he was nevertheless bound to honor his judicial responsibility to fairness and justice.82

Years later, long after the dust of the battle had settled, Vandiver would regret his stand and express remorse, especially for his racially polarizing campaign promise. “I made a major statement: ‘Neither my child or your child will ever go to an integrated school, no, not one.’ That was a statement I should not have made. Not that I’m putting the blame on anyone else, because I made the final decision.”83

Interestingly, despite Vandiver’s racist campaign slogan and vow to close the university to thwart black student enrollment, on January 19, 1961, just a few days after Holmes and Hunter entered the university, he proposed a package of bills to repeal most of Georgia’s segregationist statutes under the veil of a Child Protection Freedom of Association Defense Package.84 Vandiver, a pragmatist, sought to appease the segregationist sentiments of most whites while at the same time facing the reality of a federal court mandate that challenged the old segregationist order.

Vandiver’s so-called child protection bill and his decision not to stand in the door to bar black students, as he had promised during his gubernatorial campaign, dogged him for years among diehard segregationists. As he recalled:

I had many threats on my life. In fact, I carried a pistol for a while. . . . People would come up to me and say, “Why didn’t you fight?” I said it would not have done any good. The Supreme Court ruled. I said, “What did you want me to do, call out the National Guard and fire on Fort McPherson?” It was a situation that had to be met. I met it. I thought that I would never be elected to anything again, and I have not been. So maybe I did commit political suicide, but that was all right.85

Vandiver, the well-groomed, handpicked, would-be successor to United States senator Richard Russell, had indeed ruined his political career and in 1972 lost his senatorial bid to succeed Russell. Entrenched segregationists, who still made up a significant voting bloc, had abandoned him, and blacks, who by this time had won more voting rights, remembered all too well his infamous “No, not one” statement. Yet it should be underscored that his decision not to stand in the door to prevent blacks from entering white schools, as Governors Ross Barnett and George Wallace later did in Mississippi and Alabama, no doubt forestalled a worse riot in the aftermath of Holmes’s and Hunter’s admission to the university. In 1961, fueled by Governor Barnett’s bodily blockade and racially polarizing rhetoric to stymie James Meredith’s entrance to the University of Mississippi, mob violence led to death and destruction on that campus.86

Although Hollowell’s legal team had won a long, difficult battle to gain the admission of Holmes and Hunter without bloodshed, the two students had endured character attacks, racial pranks, and threats of physical violence. Resisting such civil rights progress in the 1960s, hardened segregationists escalated racial violence. In Mississippi, one of the better-known incidents of racial brutality was the June 21, 1964, gangland-style executions of civil rights activists Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. FBI officials recovered the bullet-riddled bodies of the three men on August 4, 1964.87

Less than one month earlier, on July 11, 1964, a tragic example of racial violence in Georgia had been the murder of Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn, a World War II veteran, assistant superintendent in the Washington, D.C., schools, and army reserve officer. Penn was returning to his Washington, D.C., home from military duty at Fort Benning, Georgia, with fellow officers Lt. Col. John Howard and Maj. Charles Brown. The black soldiers stopped in Athens, Georgia, near the UGA campus to change drivers. Klansmen noticed the out-of-state license plate and followed them as they traveled outside Athens into neighboring Madison County. Klansmen Cecil Meyers and Howard Sims fired shotgun blasts from their car that instantly killed Penn, who suffered wounds to his head and neck.

Sims was later arrested at the headquarters of the Clarke County Klavern no. 244 of the United Klans of America Inc. less than a mile from the UGA campus. According to FBI statements, the four suspects arrested and charged in the case—Meyers, Sims, James Lackey, and Herbert Guest—along with other members of the Klan frequented Guest’s garage, also located in close proximity to the university.88 Despite a signed confession from Lackey and corroborating statements from another Klansman, an all-white jury acquitted the two shooters of murder.

Following Sims’s acquittal on the murder charge, the unrepentant Klansman persisted in racially charged behavior. In a 1965 incident, Sims trailed civil rights workers to the home of Athens NAACP branch president Rev. William Hudson. Sims used opprobrious and racially insulting language in speaking to Hudson and the civil rights workers. Reverend Hudson, while standing on his own property, drew a pistol on Sims, who had threatened him. Despite Sims’s threat, his reputation for racial violence, and the widespread knowledge that he was one of the triggermen in Penn’s death, Hudson was indicted for drawing his pistol on Sims. Hollowell represented Hudson in City of Athens v. William Hudson, in which Hudson was acquitted. In a related case, City of Athens v. Joseph Howard Sims, Sims was convicted and fined $27.00 for cursing.89

In 1966, a federal jury convicted Meyers and Sims of violating Penn’s civil rights. The fact that the Klansmen’s ambush and fatal shooting of Penn was triggered merely by black men driving a car with a Washington, D.C., license plate indicated clearly the potential threat to Holmes, Hunter, and their lawyers.90 While Hollowell’s celebrated victory in the Holmes case was an important gain and a historic step for a Deep South university, the Klan murder of Penn showed that blacks continued to endure savage forms of injustice during this era.

Hollowell periodically sought assistance from Judge Bootle to guarantee Holmes and Hunter’s safety, including help with an incident that occurred shortly after their enrollment, when a deranged person carrying a gun showed up at Hunter’s dormitory.91 Despite such ongoing challenges, Holmes and Hunter both graduated from the University of Georgia in 1963, ready to embark on what would become very successful careers. Holmes, elected to Phi Beta Kappa, went on to become a highly respected orthopedic surgeon, while Hunter has achieved fame and professional success as a journalist. Besides affirming the constitutional rights of Holmes and Hunter, Hollowell and his legal team affirmed that blacks could, if given the chance, achieve great success.

Speaking at Atlanta’s Wheat Street Baptist Church, at a mass meeting designed to inform the community about the events leading up to the enrollment of Holmes and Hunter in the formerly all-white University of Georgia, Hollowell urged the overflow crowd to support the NAACP. “If you do not support every good thing in your community that is fighting to help blacks and whites alike, you are not worthy of the freedom some people are winning for you.” Tracing the history of the fight to desegregate UGA, Hollowell compared the university’s refusal to admit Holmes with its refusal of Horace Ward and noted the irony of Ward’s role in the Holmes case: “10 years ago, almost in the same month and on the same day, he was plaintiff and here he is counsel helping another black boy [Holmes] get into the University.”92

Holmes and Hunter rightly credit Hollowell for their legal victory, and they also contend that he was responsible for giving them the confidence to persevere amid formidable obstacles. In an interview, Hunter said that her relationship with Hollowell went far beyond that of attorney and client. She recalled how he had helped her gain the strength to endure the tremendous stress that she experienced in her quest to desegregate the University of Georgia: “I used to call him ‘Uncle Don.’ I wasn’t unique in that sense. He had that relationship with any student he ever represented and they would tell you the same thing. We would say, ‘King is our leader. Hollowell is our lawyer. And we shall not be moved.’ But it went beyond just the slogan; he cared for all of us as if we were, in fact, his children.”93

Hollowell’s victory in desegregating UGA was significant in civil rights history. However, despite the long, hard battle, the struggle for equity was not over, and segregationists continued trying to dissuade black applicants from attending the university. Shortly after the admission of Holmes and Hunter, Hollowell and Hill joined forces again to help another black student enter the university when Mary Frances Early, also a Turner High School graduate, sought to join her former schoolmates.94

Early was attending the University of Michigan as a graduate student supported by an “out-of-state aid scholarship,” the decades-old practice designed to keep blacks out of white schools. On January 12, 1961, she noticed a picture of Hunter in the newspaper, “clutching a Madonna and looking so despondent,” after Hunter and Holmes had been suspended. At that point she resolved that she would “join the struggle to help these two young people and do what [she] could to help end segregation that was so prevalent in the South.”95

Early began by approaching Hollowell and Hill to ask for help in transferring from the University of Michigan to UGA.96 Despite the less than month-old federal injunction banning racial discrimination that had been affirmed by the United States Supreme Court, university officials recycled some of the same tactics to deny her application. A confidential informant report revealed that university officials had Early spied on to try to discover any kind of character-damaging evidence. She was also subjected to a degrading interrogation by university officials, who asked if she had prostituted herself or visited houses of ill repute.

Despite these tactics, Hollowell, with judicial help from Bootle, was able to win the third black student’s admission to the university, this time without a bitter and protracted court fight. Early entered the university during the summer quarter of 1961 and completed her graduate degree in music education on August 16, 1962, becoming the first black student to graduate from the University of Georgia in its more than 175-year history.97

In an interview, Early remembered that Hollowell helped her many times during her enrollment at the University of Georgia. On one occasion, he sought help from Judge Bootle after UGA officials insisted that the university was not desegregated for family members of black students, and therefore her family could not attend a music recital in which she was scheduled to perform. Judge Bootle declared that the university was open to family members, but in this instance, the concert had occurred prior to Judge Bootle’s declaration.98

In discussing the reasons for the triumph in the Holmes v. Danner case, Vernon Jordan summed up Hollowell’s and Constance Baker Motley’s legal talents and commitment to obtaining social justice for black people. His retrospective view captures a dedication to community activism that transcended their roles as lawyers.

Well, number 1 . . . Hollowell and Motley were good lawyers. Number 2, and equally as important, they were committed to this process. They were acting out of a sense of duty and obligation, not just to their clients but to black people and to the country and to the Constitution. Because there was Hollowell’s talent and Connie Motley’s talent, combined with their commitment, it’s over; it’s history. The combination of the two, extraordinary legal talent plus commitment and devotion, added up to victory and it was a significant victory to open up the state university that had denied Horace Ward years earlier based on race.99

The combination of Motley’s and Hollowell’s legal talents, community activism, moral suasion, and legal action succeeded in creating an environment for positive social change.100 The desegregation of UGA was a turning point for Georgia and its recalcitrant political leaders, who finally abandoned their policy of massive resistance and accepted the start of desegregated education.101 It should also be underscored that although a violent struggle ensued at the University of Mississippi a year later, it was Hollowell’s encouragement and support of Holmes’s and Hunter’s applications to UGA that emboldened James Meredith to challenge “Ole Miss.”102 Additionally, in Meredith’s protracted legal battle against the University of Mississippi, the United States Fifth Circuit of Appeals cited the Holmes precedent in upholding the injunction against the University of Mississippi. The court specifically noted in its decision that the U.S. Supreme Court had refused to reverse the action of Judge Tuttle when he vacated the stay of Judge Bootle and ordered the admission of Holmes and Hunter.103

Building on this momentum, and despite the legal roadblocks and political rhetoric of Governor Wallace and Alabama officials, in May 1963, the LDF brought a suit against the University of Alabama that ultimately won the admission of James Hood and Vivian Malone.104 Hollowell had not only won the admission of blacks to UGA, a battle that began ten years earlier with the Ward case, but his triumph also established a U.S. Supreme Court legal precedent at a Deep South flagship school that influenced the overall legal crusade to unravel the apartheid systems at other such schools.

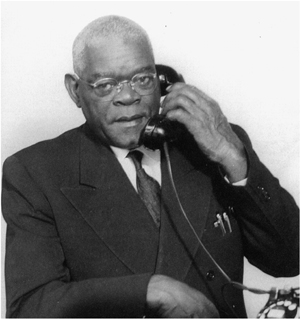

Hollowell’s father, Harrison H. Hollowell. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell’s mother, Ocenia B. Hollowell. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Donald L. Hollowell (bottom right) in a sixth-grade school photo. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

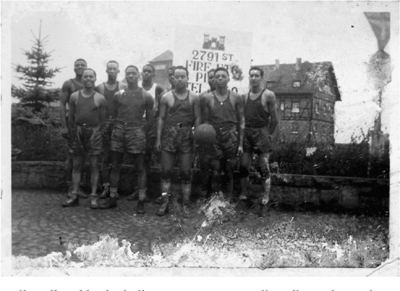

Hollowell and basketball team, ca. 1940s. Hollowell is only partly visible, fourth from left in the back row. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

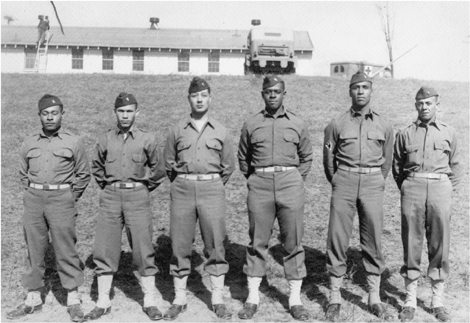

Hollowell as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Lieutenant Hollowell, fourth from left, Headquarters Company Officers. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Donald and Louise Hollowell—bride and groom—New York, Cafe Zanzibar, early 1940s. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell (“Lane College Delegate”) at the Southern Youth Negro Congress in 1946. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Horace T. Ward, Constance Baker Motley, and Donald L. Hollowell, 1961. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

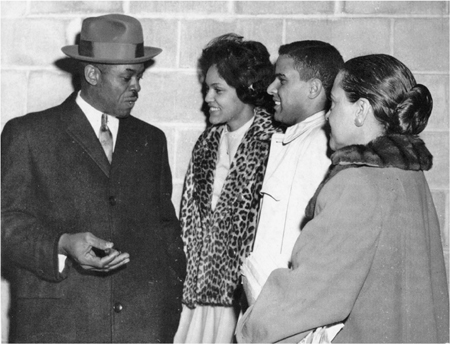

Hollowell with Charlayne Hunter, Hamilton Holmes, and Hunter’s mother, Althea Hunter, 1961. Marilyn Holmes personal archives.

Hollowell, civil rights leaders, and the press, ca. 1961. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Facing page: Hamilton Holmes (foreground) leaving the University of Georgia after attempting to register in 1961. He is accompanied by Hollowell (right) and Rev. Dr. Samuel Williams (left), president of the Atlanta Branch of the NAACP and pastor of Friendship Baptist Church in Atlanta. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

C. B. King, Hollowell, and Vernon E. Jordan Jr., Albany, Georgia in 1961. Courtesy of A. E. Jenkins Photography, Albany, Georgia.

Hollowell with Duke Ellington and Jack Greenberg at a New York City fund-raiser for Hollowell’s 1964 superior court judge campaign. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Horace T. Ward with A. T. Walden (left) and Hollowell (right) on the steps of the Georgia capitol, 1964. Horace T. Ward personal archives.

Hollowell, Constance Baker Motley, Coretta Scott King, and Wyatt Tee Walker, 1960s. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

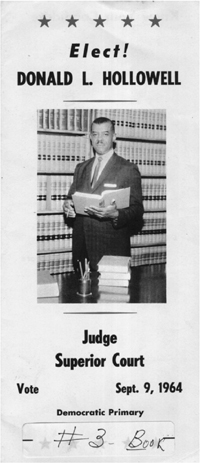

Pamphlet from Hollowell’s 1964 candidacy for superior court judge. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Donald and Louise Hollowell leaving the Atlanta Biltmore Hotel following the first integrated Bar Association dinner, 1965. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell, EEOC chairman Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., and Mrs. Lowe, New York City, 1966. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell and attorney Howard Moore with defendant Preston Cobb (center). Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell visiting with presidential candidate Jimmy Carter at a 1976 Voter Education Project dinner. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell being sworn in as honorary member of Phi Alpha Delta law fraternity with attorneys Wiley Branton, former dean of the Howard University Law School, and Vernon E. Jordan Jr., former president of the National Urban League, 1978. At far right is the late Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell and U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

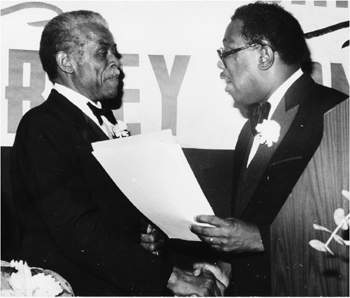

Hollowell and Marvin Arrington Sr. at Gate City Bar Association retirement dinner, 1986. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Mrs. Coretta Scott King making remarks at the Ebenezer Baptist Church Intergenerational Resource Center Tribute to Hollowell, 1990. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Iris Hollowell Baker, Corretta Scott King, Thelma Hollowell, Harry H. Hollowell, Corinne Hollowell Oliver, Hollowell, and Louise T. Hollowell at the Ebenezer Baptist Church Intergenerational Resource Center Tribute to Hollowell, 1990. Donald L. Hollowell Papers, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archives Division.

Hollowell speaks at the University of Georgia commencement ceremony, 2002. Hollowell was awarded an honorary doctor of laws degree. Photo by Peter Frey/UGA.