The meeting ran its usual course through the day. Reports and complaints were made, questions were asked and answered. None of the news was good, but Lief kept nothing back.

He knew that it was no use trying to give the people false comfort. They had eyes and ears. They knew only too well that times were hard. They would see through any pretence in a moment.

To be seen by all, he had to stand on the stairs that led to the upper floors of the palace. Just a little closer to the source of the voice that soon came back to torment him.

He fought it by keeping his hands on the Belt of Deltora—using the power of the gems, keeping his fingertips on the amethyst that soothed, the diamond for strength, the topaz that cleared the mind.

But the voice was relentless. Its poison dripped into his mind hour after hour, till his stomach was churning and his clothes were damp with sweat.

Soon, he told himself. Soon …

The Belt cannot save you, little king.

Abruptly the voice left him. His head reeled with the sudden freedom. He became aware that Barda had taken his arm, that the people were staring up at him in fear. He realised that he must have staggered.

‘I am sorry,’ he said. ‘I … am a little tired.’

‘The king must rest now,’ said Barda. ‘Thank you all—’

There was a stir from the crowd as a woman holding a sleeping baby scrambled quickly to her feet. The woman was gaunt, and her clothes, though carefully washed and pressed, were ragged. She looked nervous, but stood very straight, with her shoulders back.

‘I am Iris of Del, boot maker and mender, wife of Paulie and mother of Jack,’ she began, identifying herself as was the custom at these meetings. ‘I have a question.’

As Lief met her determined eyes, he knew exactly what she was going to ask. Plainly Barda knew it too. The big man stiffened and began to raise his hand as if to say that it was too late, that no more questions could be answered.

‘Yes, Iris,’ Lief said quickly.

The woman hesitated, biting her lip as though suddenly regretting her boldness. Then she looked down at the baby in her arms and seemed to gain confidence.

‘There is something worrying my husband and me, sir,’ she said. ‘I am sure it must be worrying many others, too, but no-one has yet spoken of it.’

Lief saw that many people in the crowd were nodding and murmuring to one another. So—the word has spread, he thought. All the better. It will make what I have to tell them easier, if they are prepared. I only wish …

He opened his mouth to speak, then froze as there was a sudden stir near the doorway. Two women shrieked and ducked, a man shouted and a small child gave a high-pitched cry of excitement.

Then the whole crowd was exclaiming, looking up.

A messenger bird had soared through the doorway and into the palace. Lief’s heart gave a great leap as it sped towards him.

‘Kree!’ Barda muttered.

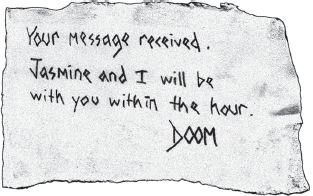

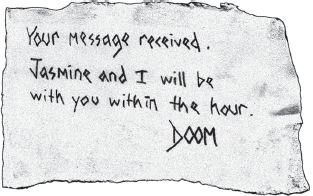

Kree landed on Lief’s outstretched arm and waited until Lief had taken the scroll from his beak before squawking a greeting. Lief unrolled the note.

‘Thank you, Kree,’ he said, passing the note to Barda. He did not know how to feel. He needed Doom urgently, and was filled with relief at the thought that Toran magic was speeding him to Del. But he would rather Jasmine had remained in the west, in Tora, where she would be safe.

Then he shook his head. How could he have thought Jasmine would agree to that?

‘I must have been mad,’ he said aloud. Barda nudged him, and he glanced up. Iris was still standing in the centre of the crowd, looking bewildered.

‘Go on, Iris,’ he said, smiling at her. ‘I am sorry for the interruption.’

The woman swallowed, tightened her grip on her child, and spoke again.

‘It sounds foolish, but Paulie and I half feared to come here today, sir,’ she said. ‘Especially as we had to bring our little Jack with us. We have heard rumours that somehow the Shadow Lord has returned—that he lurks here in the palace, in a locked room above stairs. Is that—could that be—true?’

‘No, it is not!’ barked Barda, before Lief could speak. ‘The Enemy has been exiled to the Shadowlands, as well you know.’

But Iris’s anxious eyes had never left Lief’s face.

‘We have heard that the Enemy talks to you, sir, in your mind,’ she said in a low voice. ‘And perhaps to others too, for all we know.’

‘That is so,’ Lief said quietly, ignoring the pressure of Barda’s hand on his arm. ‘And it is time to tell you about it. I was going to do so today in any case, as soon as the time for questions was over. Thank you for giving me a way to begin.’

Very flustered, not knowing whether to be pleased or afraid, Iris sank back down beside her husband. He put his arm around her and gently touched the baby’s cheek with a work-stained finger.

The room was very still as Lief began to speak.

‘On the third floor of the palace, in a sealed room, there is a thing called the crystal,’ he said. ‘It is a piece of thick glass set into a small table, and it has been in the room where it now stands for hundreds of years. The Shadow Lord can speak through it, as you or I might speak through an open window.’

A murmur of dread rippled through the crowd.

‘The Enemy once used it to talk to his palace spies,’ Lief went on. ‘Now he has begun to use it to taunt me, to distract me from my work, and above all, to try to make me despair. He torments Barda and Jasmine too. And as he gains strength, I fear he will begin on others.’

‘But can this evil not be destroyed?’ someone called from the back of the room. ‘If it is made of glass—’

‘I have tried to destroy the crystal many times, without success,’ Lief answered.

His calm voice gave no hint of what those grim, exhausting struggles in the white room upstairs had cost him. But everyone could see it, everyone close enough to see the sheen of sweat on his brow, and the shadows that darkened his eyes at the memory.

He took a deep breath. ‘The crystal was made by sorcery, and can only be destroyed by—by something just as powerful. The Belt of Deltora alone is not enough. But just before this meeting began, I suddenly saw another way. Tonight, I am going to try, one last time, to destroy this thing that threatens us all.’

‘Lief, what are you saying?’ Barda muttered.

The murmur in the crowd had risen to a dull roar. Before him Lief saw a sea of frightened, exclaiming faces. The people were afraid. Afraid for him, and for themselves. They were right to be so, but panic would help no-one.

‘I cannot do this without your help,’ he called, over the din. ‘Please hear me!’

Utter silence fell.

‘These are the things you all must do,’ Lief said. ‘When you leave here, go directly to your homes. Bolt the doors, put up the shutters and do not stir outside again until you hear the bells ring to tell you all is well. This is for your safety. Do you understand?’

The people nodded silently, awed by his seriousness.

Lief nodded. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘Now—there is something else that can be done by those who want to help further. Make yourselves as comfortable as possible, and stay awake. Stay awake through the night and—as often as you can—think of me. Send me your strength.’

‘And is this all you ask of us, King Lief?’ cried a man from the back of the crowd. ‘Our thoughts? Why, we would give you our lives!’

A great cheer rose up, echoing to the soaring roof of the great hall.

Lief felt a hot stinging at the back of his eyes. ‘Thank you,’ he managed to say. ‘I will carry your words with me. They will help me more than you can know.’

The sun had dipped below the horizon, and a huge full moon was rising, when six of Barda’s strongest guards carried a shrouded burden from the sealed room on the third floor of the palace.

The guards were grim-faced. Each one of them was astounded at the enormous weight of the small thing they carried. Each was filled with a nameless dread.

Lief walked in front of the guards, Barda walked behind. Both of them were bent forward, as if in pain. But neither paused or uttered a word as they moved along the hallway, towards the stairs.

And because they did not falter, the guards did not falter either. Suffering but uncomplaining, they heaved their hooded cargo forward, over the rubble of the bricks that had once blocked the hallway, past the old library, down the great stairway, across the deserted entrance hall, out of the palace.

Only when they had crossed the palace lawn and were moving down the hill did one of the guards speak. He was a guard called Nirrin, rescued not so long ago from slavery in the Shadowlands.

‘Where are we going, sir?’ he gasped. ‘It would help—I think—if we could know. Is it far?’

Lief turned to him. Later, Nirrin would tell his wife that never had he seen such a tortured face as the king turned to him that full moon night. Only the heavens knew what the boy was going through, what was pouring into him from that nightmare beneath the cloth.

Nirrin had volunteered for this task, and never regretted it for a single moment, though he had bad dreams for months after that terrible journey.

He had heard nothing from the crystal, but still it had touched him. Long after he carried it, the weight of its evil seemed to press him down, to make it hard to breathe, even in his own safe bed.

And never would he forget Lief’s eyes.

‘The king just stared at me for a moment,’ he told his wife. ‘His eyes were like—like deep wells. His mouth opened, but no words came. It was as if he had forgotten how to speak. Then, he croaked out an answer.

‘“Not far,” he said. Then he pointed down the hill and across a bit, and I could see a sort of glow through the trees. “Only to Adin’s old home, and mine, Nirrin. Only to the forge.”’