THE FAT-EATERS BELIEVED the ancestors returned in the new bodies of children, so for several weeks Tulik, Auntie, and the woman named Luce studied Aurora’s features to see who she might be.

They pondered her, but there was great disagreement. “Look. That birthmark at her hairline is just like Ek’s,” said Auntie.

“No, Ek’s was on the other side of her forehead.”

Tulik said, “Ek was her own grandfather. Remember?”

“But her expression is just like that of Ek’s. Isn’t that so, Dora-Rouge?” Auntie tried for support. “Doesn’t she look like your mother?”

“Leave me out of it,” said Dora-Rouge. “I love her whoever she is.”

But the arguments over Aurora continued. Luce, who wore a calico dress, favored Auntie’s opinion. “She’s just like Ek. Look how she keeps crawling toward Ek’s book. See? She’s doing it now.”

This was the first time I’d heard of Ek’s book. “What book?” I asked.

“Yes, I have her book. But it’s yours. It’s for you women.”

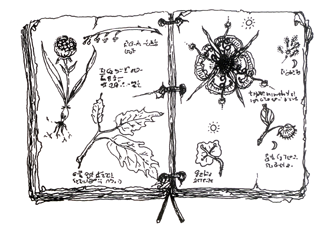

The book’s pages were made of thin birch bark cooked into a stew of salt and ash, then flattened and dried. In it were diagrams of plants. Arrows pointed to parts of them that were useful for healing a root, a leaf. Also there were symbols for sun and moon which depicted the best times of day to gather the plants.

IT WAS TRUE that Aurora went often to this book written in another alphabet. She would put out her hand, reaching toward it, the little table where it rested, chattering in innocent baby talk, speaking the before-language words.

Personally, I didn’t like the notion of returned souls. I believed in newness, in the freedom of a beginning outside the past, outside history. Maybe it was because I had fallen into my own life so late or because I had grown up in the white world and only come home so recently.

But out of plain stubbornness, Tulik began to call Aurora “my grandfather,” and he named her privately after his mother’s father; Totsohi, which meant Storm. Totsohi was a man revered for his intelligence, generosity, and kindness. He had been a keeper of peace.

While it was true Aurora had peaceful, knowing eyes, like those of an older person, I complained, “That’s a big order to fill when she doesn’t even know how to walk yet.” But they all turned a deaf ear to me.

Sometimes when Aurora’s eyes sharpened or looked especially wise, Tulik would say, with pride, “See? There he is. It’s Totsohi himself!” Or if Aurora was very serious and took him in with a long look, Tulik would say, “Totsohi is always such a thinking man.”

Once Aurora said something that sounded like Tulik’s name. This heartened him. His face lit up. “He remembers me!”

Finally, I found a way to break him of this habit. When he told me one day, “My grandfather has a wet diaper,” I took hold of the opportunity. “You’d better change him then,” I said. “I don’t want to see an old man naked. It would embarrass him.” I handed Tulik the cloth.

After that, Tulik called her Aurora whenever I was around, but when he thought I wasn’t listening, the times when I was in “my” corner of the room, or sitting outside in the white chair, I heard him speak with her. “What do you think a human is, Grandfather? I’ve been wondering this all my life.” Or he’d speak about the old times, or ask if Totsohi remembered the time the horses froze standing by water. “I still can’t get it out of my mind,” he said.

Because of Aurora’s ancient history, she was treated with great respect, as if she were an elder. It was good, I thought, when I cradled her and looked down into her small, round face. It would help her grow into a strong woman. She would be what I was not. She would know her world and not be severed from it. Whoever she was, it was a kind of beginning, I reasoned, because all the parts of her were new and fat and laughing.

Tulik tied the old man Totsohi’s flint, what Totsohi had called a living stone, around her neck. That was how Aurora, my baby sister, became the man who had dreamed sickness and foretold the measles, who had warned the people that these diseases would kill them. She became the man who knew the songs of the water and beaver. And maybe she was part Ek, too.

I HAD A FEELING all along that Husk would not come, but I hoped I was wrong. On the night before he was to arrive I prepared for his arrival. I put pictures on the wall. He liked that, Husk did. Tulik cleaned the floors. I washed the small windows until they were invisible and streakless. Then, on the morning of the fifth, I put the bedding out on the whalebone fence to air, picked wildflowers and arranged them in jelly glasses to spruce up Tulik’s house. Everything was bright. I was excited that John Husk was coming and that Tommy, I hoped, might come with him. I still thought of Tommy daily, and sometimes at night I pretended we were together in each other’s arms.

On the morning of the fifth, Dora-Rouge and I went to the String Town depot, a little wooden building with coal still sitting in a bin outside the door. But noon arrived and no train appeared. The day wore on. No Husk or Tommy arrived. My heart fell.

“What do you think?” Dora-Rouge said, frowning. “It’s not like John. He always does what he says.”

“But maybe it’s not him. No trains at all have come in, just that empty one.” It sat, its cars empty with waiting.

Soon we learned that a security force was being sent in. By now, we knew what that meant. It meant there were plans under way to begin blasting and construction once again. The only people who were able to pass through were what Bush called the soldier police, already prepared for our resistance. A roadblock was in effect. No one could travel Highway 17. And no one could come by train. The trains were carrying only freight and emptiness to be filled, and they were guarded carefully against human travel.

I cried, “I hate this place.”

“Shh. It’s all right, Angel.”

Later that same day a light rain fell on the bedclothes laid over the whalebones, but I was too depressed to care.

That night I could not sleep. I held Dora-Rouge’s sleeping potion in my hand wondering if I should swallow it. I’d preserved and guarded what was left of the concoction. I looked daily at the amount left in the brown glass bottle, afraid to use it, saving it for when my insomnia might worsen, afraid it would evaporate or I would drop it, afraid it would lose its strength. It seemed selfish of me to use it; the plant that went into it, like the one for headache, was beneath water now. Dora-Rouge had sent several people searching for it, but it was nowhere to be found and this added to Dora-Rouge’s heavy grief that one more sacred thing was missing from the world.

I lay there listening to the rain, smelling it. I was lonely. In a house filled with the snores and breathing of others, I was all alone.

We learned later that Husk and Tommy, reaching the roadblock, were turned back. They tried to take to the waterways in order to reach us, but were intercepted.

During the few times I slept, when a few hours of darkness went through my thoughts, I entered a world of green, a tangled-together nest of growing things. At times now it was an autumn world I saw, with white seedpods and silver filaments flying into warm air, desperate and urgent, seeking a resting place, a place to grow. There were burrs carried to new places in the fur of wolves and other animals, seeds dispersed by birds. At times I’d see the ancient lichens awake on rocks, and green mosses, soft as clouds.

When Dora- Rouge told Tulik about the plants that grew in my sleep, he said, “Dreams rest in the earth.” By that he meant that we did not create them with our minds. One day, after I’d drawn a plant, he said, “I know where that one is. Come on.” With great energy, he prepared to find it, rain or shine. We went searching for other plants, too, me wearing my rubber boots, trying to keep up with him. We tramped across land and swamp. As we walked through mosses, Tulik pointed out landmarks. We searched for the little elk lichens that grow at the edges where light and shadow meet. We canoed through marshes and waded in mud.

Some of the plants we would cut. Others had to be pulled by the roots, but only if there were enough left to survive. Each had its own requirements. We were careful, timid even, touching a plant lightly, speaking with it, Tulik singing, because each plant had its own song.

“I feel stupid, talking to plants,” I said to Tulik one day.

“What’s wrong with feeling stupid? Entire countries are run by stupid men. But,” he said, “soon you won’t feel that way.”

Some plants we tied with string and hung from the dark ceiling of Tulik’s house. Some we let dry for several days. Later we’d boil a plant or powder it and mix it with fat into a paste, with Tulik stirring the dark, bitter liquids until the house smelled dank with the mustiness of remedies. Some plants were from marshes, others from meadows. All were our sisters.

I sampled all the remedies and teas, sometimes drinking the bitterness of wormwood or maybe a cup of bluestem, to see what its effects were, all the time telling the plant, “Thank you,” because you have to speak with the plants even if it feels foolish. There was the mikka plant that took down the heat of inflammation, and scilla, a tea that would open the body for childbirth. I tried the salves, ate the soapy-tasting mixtures. I began to learn them and soon, as Tulik had said, I no longer felt embarrassed.

“Sing over this,” Tulik said one day, handing me a leaf.

“But I only know a death song.” All I remembered was Helene’s song and I was forbidden to sing it. I couldn’t remember Dora-Rouge’s animal-calling song, though I recalled the sound of it.

If all of Tulik’s remedies failed to help an ailing person, if all his roots and songs and teas were ineffective, Tulik sent for a woman from the east. She came when there was nothing to be done but to sing into the patient, to place new songs inside their body, songs that would replace illness with a song of mending. The woman’s name was Geneva and she seemed to shine with a kind of inner light. I thought of her as something like the sun, appearing from the direction of dawn, walking toward us from the eastern morning light. Geneva had a graceful walk and quiet ways, and even though I thought of her as an old woman, I realize looking back that she wasn’t much over forty.

Geneva traveled with a girl a few years younger than I was. I didn’t know the girl’s real name, but we called her Jo. On the first day Geneva came with this young apprentice. Jo and I became fast friends. We were rare, younger women who lived with older people and learned from them, but even if we hadn’t had that common bond, I would have loved Jo. In some ways, she was like a wizened old lady. In others, she was light and young. When she walked it was with an air of floating; she was quiet with an inner happiness. She specialized in treating bronchitis, yet she was still young enough and modern enough to say things like “That’s cool.”

Jo wore jeans and a single long braid fell down her left shoulder. She was skinny and tall and looked like a no-nonsense woman one minute, but in the next she could be a girl again, laughing, her voice almost like the sound of glass or bells.

I looked forward to the appearance of Jo even though she only came when someone was in pain or sick.

One day an old man at the settlement had something like a stroke and could not get up out of bed. I’d gone to the square little house with Tulik and the two women. The man was tired-looking, and his head was turned to the side; his eyes were open, but he couldn’t move. He was covered by a white sheet, his arms on top of it. When Geneva and Jo arrived, they stood on either side of him and sang. When the two women opened their mouths to sing in the small, tan-painted room, the sounds that came out were like nothing I’d heard before.

I was greedy to learn the songs. “Teach me,” I said. “I want to know that song.” And we would walk through the grasses laughing and singing, me sounding terrible, barely even able to keep time. Jo hardly noticed that I had no gift or talent, barely even a voice.

In those days, we were still a tribe. Each of us had one part of the work of living. Each of us had one set of the many eyes, the many breaths, the many comings and goings of the people. Everyone had a gift, each person a specialty of one kind or another, whether it was hunting, or decocting the plants, or reading the ground for signs of hares. All of us together formed something like a single organism. We needed and helped one another. Auntie was good at setting bones, even fractures where bone broke through skin. I was a plant dreamer, even though I barely understood what that meant. Tulik knew the land and where to gather herbs, mosses, and spices. He knew the value of things. Dora-Rouge knew the mixtures, the amounts and proportions of things.

Bush, too, had another gift, among her many, though I’d been led into thinking her skills were only those of fishing, hunting, and making financial deals with shopkeepers. I might never have known Bush’s other gift except for the day I was at the stove putting pieces of cut meat into a kettle of hot lard. Outside, a terrible noise, a dynamite blast, broke through the land. I jumped, turned suddenly, a careless movement, and the kettle of boiling grease tipped over. My arm was burned badly, seared. I could tell at once that it was a terrible burn. I cried out. I smelled my own flesh cooking and it made me sick. Aurora yelled, too, as if to match my screaming. Without wanting to, without knowing it, my legs ran out the door and down the slope to the ice-cold water. Tulik followed behind me, unable to keep up, calling, “Angel!”

I ran from the fire until winded. I fell into the water, lay down inside its coolness.

Auntie had followed behind Tulik, and as Tulik reached me, he shouted at her, “Get Bush. Hurry!” He yelled in the old language so I wouldn’t hear him. But I understood him. He said, “It’s a bad burn. Very bad.”

Auntie turned and ran toward the meetinghouse.

At the water, he leaned over me. Tulik was so tender. He couldn’t bear for me to feel pain. His eyes were filled with tears.

By the time Auntie returned with Bush I had stopped screaming and become silent and still.

Then it was Bush who bent over me, breathless from running, her face near mine. She lifted my arm from the water and looked at it. And when she put her hand over the heat, I screamed, “No! Don’t touch it!” By then I was shivering from the cold.

But she said, “It’s okay. It’s going to be all right.” As cold as it was, she lay down beside me.

“It’s bad, isn’t it?” I asked, remembering the smell of my own flesh burning. I felt strangely disconnected from my body, from the pain I knew was there. Then I felt sick and started to cough.

Bush took hold of my arm, held her head over the burn. “Hold still.”

I saw her hand become very red. She spoke to the burn, spoke with it, and said, “Burn, go away. Coolness enter.” With closed eyes, she said, “Heat, leave this skin.” She said this in many ways, as if trying to get the language right.

To my surprise the pain began to dim. The heat of it began to cool.

I’d burned my thigh as well, but didn’t notice it until later. Some of the hot grease had splattered into my right shoe.

By evening, the pain had lessened enough that I could rest and sleep. Tulik looked in Ek’s book to see what to use for fever. “Three-leaf,” he said. He went out the door, returning a few hours later with muddy boots, a sweat-stained shirt, and the little plants that looked something like clover.

I slept that night on the bed where Tulik usually lay, behind the dark curtain, on a fur, soft and comforting. The bed smelled of Tulik, of fresh wood and sunlight. I slept.

By then Tulik had sent for salve from Geneva. The salve arrived later that night. It had been carried by runners. They’d sent the message from town to town, then returned the jar of salve in the same way, each one passing it to another as in a relay.

I had a slight fever. Bush said she thought it was from the burn itself.

Later I lay there thinking of the words Bush had used to talk fire away. I’d never heard of such a thing before. Every new thing I learned about her raised her in my esteem. Bush was still coming together in my mind.

Later I learned that there are those who can stop bleeding just by talking to it. It seemed too simple. I wondered if I could talk loneliness away, or scars. Maybe it was how Dora-Rouge had talked with the water or how Agnes had spoken with, and learned from, the bear.

AURORA WAS THE CHILD of many parents. We shared in her care. At night, in my wakings, I tended to her. Sometimes when she cried out with a dream, Bush picked her up and carried her about until she slept again. Or Tulik would stand beside her and speak with her, calling her “my grandfather,” and saying such things as, “Although this world is painful, be glad you are here with those who love you.” Auntie, of course, slept much too soundly to hear the child, or at least that’s what she said.

Sometimes now, even as the summer diminished, there was a kind of twilight. On those nights when I was awake in the soft shadows of night, I would look at the face of Grandson, then slip outside, into the intimidating beauty of the land. I’d walk down close to water and look across at an island in the lake. This island meant much to me because of the stories told about it and my ancestors who went there and what befell them.

It was the island where Ammah, one of the creators of life, lived. On Ammah’s little island were shining things, things that grew. Ammah was the one light that remained in the shadowy history that had nearly obliterated our world. Ammah fed all life and was its protector. On the little island were seeds, grains and grasses, nests and eggs. Some of the nests were nests made with the translucent, blue-edged wings of dragonflies, and these, I was told, shone with moonlight. The silky down of plants was stirred up in every passing breeze. Ammah was the protector of spring eggs, caretaker of the abandoned nests of winter, of the unborn, of promise.

One of the trees on Ammah’s Island had been toppled under the five-hundred-pound weight of an eagle nest and even from a distance I could see its roots sticking up like thin fingers from the ground, reaching toward the moon. There, also, some trees were new, infant trees rising out of those that had decayed and fallen.

The seeds of corn lived there. An old man, long before Totsohi, had left the seeds from the journey south in a clay jar for Ammah to watch over. It was from the same corn Dora-Rouge possessed.

Ammah’s Island was a place of hope and beauty, and no one was permitted to walk there. Never could we put a foot down on it. No person could trample hope, could violate the future. But at times, some days, I sat in a canoe and daydreamed out across the water at the place Ammah protected, and I liked to see the island on my sleepless nights and mornings. I was told Ammah was a silent god and rarely spoke. The reason for this was that all things—birdsongs, the moon, even my own life—grow from rich and splendid silence.