The low-budget house is shoehorned into a narrow urban site with amazing dexterity.

The house seen in its urban context.

Ahmad Djuhara was born in 1966 and graduated from Parahyangan Catholic University, Bandung, in 1991. He was first employed by Pacific Adhika Indonesia (PAI, 1992–8), later taking up an appointment with Jeffrey Budiman Architects (1999–2001). His designs have won a number of awards, including first place for the Megolopolis Gallery House, Tarumanagara University, Jakarta, in 1997, and an honorable mention in the JakArt@2000 Jakarta Arts Festival for an arts center selected by the sole American juror, architect Antoine Predock.

He established his own firm, Ahmad Djuhara, in 2001, and since 2004 has been in partnership with his wife Wendy in the firm djuhara + djuhara. Wendy Djuhara graduated three years after her husband from the same university and also worked with PAI, in her case for ten years. Their design for the Museum Wayang extension in Jakarta won first place in a competition organized by the Jakarta Chapter of the IAI and the Bureau for Culture and Museums in 2004. Both Ahmad and Wendy Djuhara are active members of Arsitek Muda Indonesia (AMI) and are occasionally referred to as the AMINext generation.

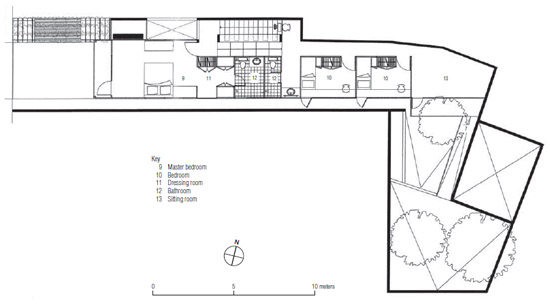

The Wisnu House is a modest town house shoehorned into a relatively tiny urban site at Perumahan Graha Indah in West Java. The site is approximately 5 m wide and 30 m deep, with a garden at right angles at the rear, the whole totaling 242 sq m. The house has a footprint of 5 m x 25 m and a built-up floor area of 215 sq m. Ahmad Djuhara explains that “The project was offered to djuhara + djuhara after Nugroho Sundari and Tri Sundari had seen the architects’ earlier design for the low-budget Steel House at Bekasi. The clients were living on the site in a tiny 36-m terrace house on a 78sq m plot. Piece by piece they bought the land behind their house, eventually acquiring a total of 242 sq m sloping down from the rear boundary. After buying the land, they had a limited budget to build the new house, which presented a challenge to the designers.”1

The concept was to erect a “floating” box that shelters an open space at ground floor—a modern interpretation of the traditional rumah panggung (platform house). The ground floor is devoted to the living, dining and kitchen spaces, whereas the “box” above contains bedrooms, a sitting room overlooking a garden and a study. Wendy Djuhara explains that “the original idea of the floating box was influenced by cost considerations. The narrowness of the site allowed us to only build on the second level, while achieving an additional open living space below, perfect for living in the tropics.”

The ground floor has a hinged steel metal gate at the front, with a smaller steel side gate, which functions as the main entrance to the house. The entire frontage can be opened up to connect the interior to the front garden and the public space across the street that contains a communal garden and sports facilities.

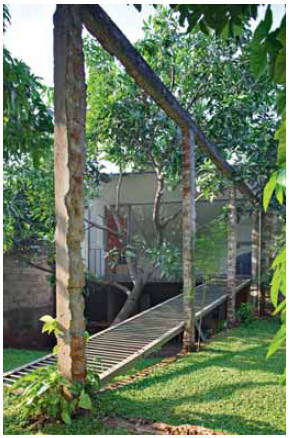

With the limited budget available, the basic structure of the house consists of concrete columns, beams and slab because, at the time of construction, a concrete structure was less expensive than a steel one. But the upper floor has a lightweight structure just 4 m wide consisting of a steel frame roofed with a metal deck. The main façade of the house, facing the street, is clad in reclaimed timber, intended to shield the interior from the western sun in the afternoon. The upper floor is accessed by a stair adjacent to the house entrance and also from the rear garden by an inclined steel bridge. Along the south flank of the building, a 600-mm gap has been left to permit sunlight to enter and also to allow rain to fall into a channel that directs water to the front of the site. The open-sided concept at ground-floor level permits cross-ventilation and allows the occupants to live without air-conditioning.

The design is conceptually a floating box that opens up the ground-floor space,

The kitchen/dining space looks out to a quiet rear garden.

The house is designed for a family of two adults and two children and a live-in maid. Unusually, the servants’ quarters are located at the front of the house, giving the domestic staff easy access, adequate sunlight and ventilation and responsibility for providing security for the house. This is a further development of the experimental design approach in the architects’ earlier design for the Sugiharto Steel House. It brings the so-called back yard into use as the family recreation area, rejecting the notion that it is a back-of-house space for kitchens and domestic staff. Ahmad argues that the common perceptions of housing can be critically challenged through such design exploration.2 Asked to reflect upon architects who have been influential in their careers, the Djuharas name Tom Elliott and the late Richard Dalrymple, both architects in PAI, together with Irianto Purnomo Hadi, the first “president” of AMI, in addition to Japanese contemporary architecture.

The house is designed with immense ingenuity, with overlapping functions and multiple levels. Ramps between floors follow the sloping topography and enable easy access. Like a “Matryoshka (Russian) doll,” the house opens up to reveal numerous layers, with infinite possible variations of layout. Architect Danny Wicaksono observes that “Everyone who visits the house feels that this is a place that they could live in and they would feel comfortable in.”3 This a perceptive remark for, although of modest size, the house embodies the “original” idea of a “home,” not least being the way its location and openness show faith in the enduring quality of community.

Ahmad accepts the opinion but responds: “I feel that this house is not a house for everybody. It takes some guts to live in such an extraordinary design in Jakarta or Indonesia, with open space at ground floor. It is even intimidating.” More importantly, the house indicates how, with ingenuity, beautiful spaces can be created on a modest budget.

There is considerable ingenuity in the overlapping of functions within the plan.

The front façade of the house is clad in reclaimed timber.

Light penetrates through the timber screen and casts a gentle filigree throughout the interior.

The concrete frame provides a memory of a former structure on the site.

An inclined bridge leads from the garden to the first-floor family room.

The interior has multiple levels with connecting ramps.

A hinged metal gate at the front of the house can be opened to connect the interior with the forecourt.

First floor plan.

Footnotes

1 Ahmad and Wendy Djuhara in conversation with the author, October 20, 2009.

2 Amanda Achmadi, “Ahmad Djuhara: Steel House, Bekasi, Jakarta,” in Geoffrey London (ed.), Houses for the 21 Century, Singapore: Periplus Editions, 2004, pp. 102–5.

3 Danny Wicaksono in conversation with the author, October 18, 2009. Wicaksono is joint Editor-in-Chief of Jong Arsitek, a free architectural e-magazine based in Indonesia.