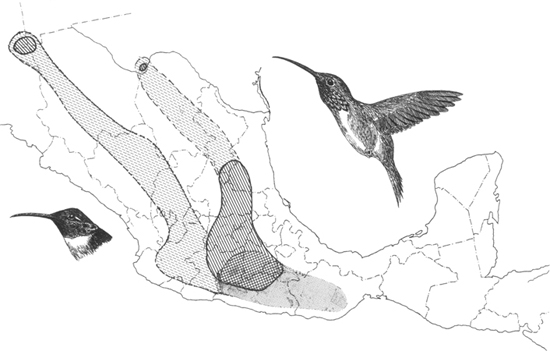

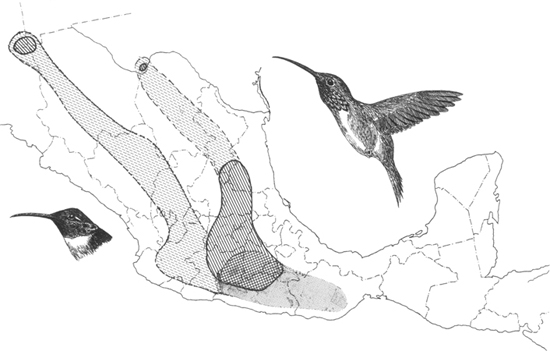

Breeding (hatched), residential (cross-hatched), and wintering (shading) ranges, plus migration routes (broken hatching) of the lucifer hummingbird.

None in general English use; Chupamirto morada grande (Spanish).

Breeds in southwestern Texas (Chisos Mountains), southward through central and southern Mexico to Guerrero, mostly at elevations of 1200 to 2250 meters. Migratory at northern end of the range. Has bred in southern Arizona; probably a regular breeder in adjacent Sonora.

None recognized.

Wing, males 36–39 mm (ave. of 10, 37.6 mm), females 39–44 mm (ave. of 8, 41.2 mm). Exposed culmen, males 19.5–22 mm (ave. of 10, 21.1 mm), females 20–22.5 mm (ave. of 8, 21.2 mm) (Ridgway, 1911). Eggs, ave. 12.7 × 9.7 mm (extremes 12.0–13.8 × 9.2–10.1 mm).

Thirteen adult males from Arizona averaged 3.2 g (range 2.9–3.7 g); 5 females averaged 3.3 g (range 3.2–3.5 g). Nine females from Texas averaged 3.5 g (range 3.1–3.9 g); 3 males averaged 3.4 g (range 3.1–3.6 g) (Scott, 1994).

Adult male. Above metallic bronze, bronze-green, or golden green, usually duller on pileum, especially on forehead; remiges dull brownish slate or dusky, faintly glossed with purplish; four middle rectrices metallic green or bronze-green, the rest of tail purplish or bronzy dusky or blackish; a small postocular spot (sometimes also a rictal spot) of dull whitish; chin and throat brilliant metallic solferino or magenta-purple, changing to violet, the posterior feathers of sides of throat much elongated; chest dull white; sides and flanks mixed light cinnamon and metallic bronze or bronze-green, the median portion of breast and abdomen pale grayish or dull grayish white; under tail-coverts dull white with central area of pale brownish gray; femoral tufts white; bill dull black; iris dark brown; feet dusky.

Breeding (hatched), residential (cross-hatched), and wintering (shading) ranges, plus migration routes (broken hatching) of the lucifer hummingbird.

Adult female. Above as in adult male but lateral rectrices much broader, the three outermost (on each side) with basal half (approximately) light cinnamon-rufous, then (distally) purplish black, the two outermost broadly tipped with white, the black terminal or subterminal area on second and third separated from the cinnamon-rufous of basal portion by a narrow space of metallic bronze-green; fourth rectrix (from outside) mostly metallic bronze-green but terminal or subterminal portion blackish and outer web edged basally with light cinnamon-rufous; a postocular spot or streak of cinnamon-buff, and beneath this a narrow auricular area of grayish brown; malar region and underparts dull light vinaceous-cinnamon or cinnamon-buff, passing into dull whitish on abdomen; the under tail-coverts mostly (sometimes almost wholly) whitish; femoral tufts white; bill, etc., as in adult male.

Immature male (first winter). Similar to adult female, including broader tail feathers, but darker above and below, size smaller, throat with some metallic purple feathers (Oberholser, 1974).

Immature female (first winter). Similar to adult female (Oberholser, 1974).

In the hand. Unique among North American hummingbirds in having a blackish (culmen 19–22 mm) bill that is more than half as long as the wing and distinctly decurved. The underparts are buffy to pale buff. The tail of the male is deeply forked; that of the female is rounded, with a tawny base and white tips.

In the field. Inhabits open desert-like country, often where agaves are abundant, and the long and decurved bill is the best fieldmark for both sexes. The male is about the same size as the Costa hummingbird, but has a deeply forked tail and lacks red color on the forehead. The female resembles several other hummingbirds but, apart from the longer bill, the pale cinnamon-buff underparts and the tawny color at the base of the tail are fairly distinctive. The birds utter shrill, piercing shrieks when defending their nest; other calls have not been described.

In the Chisos Mountains of the Big Bend area of Texas, lucifer hummingbirds occur from May through early July on the open desert or on the slopes of the mountains up to about 1500 meters. During late July and early August, after breeding, the birds begin to move upward into various canyons such as Boot Canyon at 1900 meters (Wauer, 1973). They sometimes occur at higher altitudes as well; as many as 10 individuals have been seen near the South Rim of these mountains at about 2200 meters in mid-July (Fox, 1954). Actual nests in the area have been found from 1100 to 1500 meters. The first Texas nests were found in a desert-like habitat dominated by agave (A. lechuguilla), sotal (Dasylirion leophyllum), and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) (Pulich and Pulich, 1963). Associated plants included candelilla (Euphorbia antisyphilitica), catclaw (Acacia greggii), mormon tea (Ephedra), yuccas (Yucca species), and cacti. Blooming cacti provided the principal source of food during the unusually late nesting observed by the Pulichs.

In northern Sonora, 30 females were found along a 3-kilometer stretch of Arroyo Cajon Bonito at about 1200-meter elevations. There they nested among sycamores and hackberries and foraged from streamside upward along the drier upper slopes, where agaves were in flower (Russell and Lamm, 1978). More generally in Mexico the species is found in open country having scattered trees and shrubs and among brushy vegetation in arid areas. There is no special marked preference for any particular species of plant nor for any specific altitudinal zone (Wagner, 1946b).

In Texas, this species arrives as early as March 7 and has been reported as late as November 12 (one winter record exists for January 4). Typically it arrives during March, with males preceding females by a few days. By late August the birds are moving toward lower canyons, where they remain until about the second week of September. Between then and November the birds move back to their winter territories in the Mexican desert (Oberholser, 1974).

Vagrant birds in Texas sometimes reach the Edwards Plateau, more rarely the Gulf Coast (Rockport, Aransas County). Other than Texas, the species is essentially confined to Arizona, where it is very rare but where nesting has been reported (American Birds 27:804). There is also a single state record for Williamsburg, New Mexico (American Birds 33:796).

In the Valley of Mexico, seasonal movements of these birds are associated with variable availability of foods; there are few plants during the winter months (Wagner, 1946b).

The relatively few observations of lucifer hummingbirds suggest that it consumes a fairly high proportion of insects in its diet, and its attachment to flowering agaves is probably in large part associated with the abundance of small insects usually found around these plants. In Texas, the overwhelming favorite plants from May through September are the yellow-green blossoms of several agaves (A. americana, A. chisoensis, A. harvariana, and A. lechuguilla). In early spring the birds also visit Chiso bluebonnet (Lupinus havardii) and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens), and late fall migrants often concentrate on tree-tobacco (Nicotiana glauca) that has been planted along the Rio Grande (Oberholser, 1974). The species also has been observed foraging at the blossoms of Erythrina coralloides and E. “corallodendrum” (Toledo, 1974).

Wagner (1946b) reported that 11 stomach samples that he examined invariably contained insects, spiders, and other small animals, particularly dipterans. These insects are extracted from flowers of Erythrina americana, Salvia mexicana, Loesalia mexicana, Lupinus elegans, and other plants, including eucalyptus and Opuntia cactus. Sometimes the birds also resort to removing entangled flies from spiderwebs (Bent, 1940), but they do not hawk them in flight.

Although few actual nests have been found in Texas, the breeding season there probably extends from May to July. Nests have been found from May 8 to August 2, and very recently fledged young have been observed between June 8 and the first week of August. There are now at least six nesting records for the Big Bend area (American Birds 32:1026). The single-reported Arizona nesting of this species was in Guadalupe Canyon, Cochise County, in May 1973 (American Birds 28:920).

In Mexico, breeding likewise seems to occur in the summer months. Bent (1940) reported six Mexican egg records from June 15 to July 4; most were from the state of Tamaulipas. In the Valley of Mexico, the principal breeding period is between May and September, with extremes of April and October (Wagner, 1946b).

Feeding territories in the Chisos Mountains are sometimes associated with the distribution of flowering agaves. The territory of one male contained two agaves along a cliff edge, and from them extended 6 meters on each side to some low trees, and 4.5 meters backward from the edge to another small tree (Fox, 1954). All but two of six observed males defended feeding territories, which usually consisted of circular areas having 12-meter radii. In one of the two exceptional cases, one male shared some agaves with black-chinned hummingbirds, and another male partially shared its territory with the first. Of two females, one showed partial possession of her area, while the other apparently visited undefended agaves. Two immature birds were evidently non-territorial. Wagner reported that in Mexico the calculated size of a male breeding territory was 30 to 50 meters in diameter—considerably larger than the feeding territories reported by Fox.

The first two nests discovered in Texas were both placed in agave (A. lechuguilla) stalks, about 2 to 4 meters above the ground (Pulich and Pulich, 1963). Four nests found in Tamaulipas were all placed in shrubs, again only a few meters above ground (Bent, 1940). Four nests observed by Wagner were in low shrubs (Senecio salignus) about 1 to 2 meters above ground. The two nests found in the Chisos Mountains were similarly constructed. Both were placed on two or three dried pods that were attached to the stalk. On these pods the birds had made a foundation and constructed the nests of plant fibers, grass seeds, and pieces of leaves. Both were lined with plant down and feathers, and one was decorated externally with small leaves. The other nest, still unfinished, was undecorated. Neither contained lichen decorations, although this seems to be typical of nests found in Mexico (Bent, 1940; Wagner, 1946b). A third nest found in the Big Bend area was located almost 2 meters up in a dead shrub, but with flowering individuals of Agave lechuguilla in the vicinity (Nelson, 1970).

Nests in Texas are usually placed on the live or dead stalks of cane cholla, on dead lechuguilla stalks, or on leafy branches of ocotillo. Sometimes nests are placed on the old nests of the previous year, but females that begin a second clutch while still feeding nestlings build their second nest at a new site. Male lucifer hummingbirds are the only North American hummingbirds known to display to females that are sitting on their nests, including not only incubating females but also those tending nestlings. Such courted females may remain on the nest or may take off and ascend with the male, either chasing him or facing and hovering upward with him. The most typical displays performed by males in Texas are shuttle flights lasting 30 to 45 seconds, and having associated wing or tail sounds that sound like card-shuffling noises and that can be heard at least 100 meters away (Scott, 1994). Presumably the courting of nesting females is an adaptive behavior for any regularly double-brooding species.

According to Wagner (1946b), courtship has two phases. The first is to attract the female and induce her into copulation, and the second is simultaneously performed by both partners. The first of these is a display flight by the male, performed daily in the same place, usually in the first 5 hours after sunrise. Its form is variable, but in part consists of repeated lateral flights between two perches on a tree or bush. At greater levels of excitement the male may ascend vertically upward in a spiraling flight and then pitch downward again to a perch. The more rarely seen second phase was observed once by Wagner a short time after dawn. In this case a male performed before a perched female, beginning his display with a sharply ascending and somewhat spiraling flight upwards for about 20 meters. At the peak of the ascent the bird hovered in place, and then began a rapidly descending swoop toward the female, pulling out of the dive while still some distance above her, and terminating the descent with a series of pendulum-like swings of decreasing amplitude as he slowly descended toward her.

The flight terminated with the male again gaining altitude. The dive was accompanied by a sound resembling that of an electric fan, but apparently lacked vocalizations (Wagner, 1946b). This display has some components, especially the pendulum-like swinging, very much like that of the Bahama woodstar; it also resembles the display dives of Archilochus and Selasphorus to some degree.

Details of incubation and brooding behavior are not well known, but Wagner (1946b) estimated that the incubation period is 15 days from the laying of the second egg to the hatching of the first egg, or a total incubation period of 15 to 16 days. Incomplete observations indicated a fledging period of 22 to 24 days. Similarly, Pulich and Pulich (1963) estimated the fledging period at 21 to 23 days, also on the basis of incomplete information.

Recent observations by Scott (1994) support the 15-day estimate for incubation, and a nestling period of 19 to 23 days. The fledglings remain near the nest and are fed for 13 to 19 days after leaving the nest. The female’s care of the nestlings may be combined with nest construction and incubation of a second clutch.

The unusually long and decurved bill of this species is not associated with obtaining nectar from unusually long tubular-blossomed plants, but instead may principally serve for extracting insects from plant blossoms and perhaps similar recesses. It thus seems somewhat comparable to the starthroats, which also have unusually long bills and apparently feed largely on insects rather than nectar. The starthroats often hawk insects during flight, however, which is rare for lucifer hummingbirds.

Taxonomists have generally maintained the genus Calothorax exclusively for the lucifer hummingbird and a very closely related species—the slightly shorter billed beautiful hummingbird of southern Mexico. These two forms clearly constitute a superspecies. They are also obviously very close relatives of the sheartails (“Doricha”) of the same general area, differing from them only in the longer and more deeply forked tails of the males. I can see no reason for maintaining these two genera as distinct, nor for excluding some of the “woodstars” from the same genus. Other Central and South American genera such as Acestrura, Chaetocercus, Philodice, and Calliphlox may be part of the same assemblage, but no detailed comparisons of these types have been made in the present study.

The very small size of this species probably places it at a competitive disadvantage with many other sympatric species, and Fox (1954) noted that black-chinned and broad-tailed hummingbirds sometimes trespass on the territory of a male lucifer. However, a female drove away an immature magnificent hummingbird and some black-chinned hummingbirds from one agave, but another was driven away from an agave by a male black-chinned. There are apparently no plants that this species has specifically become dependent upon, although several observers have commented on the attraction of lucifer hummingbirds to flowering agaves.