6 Policy implementation, productivity, and program evaluation

Local government managers strive to deliver programs efficiently and effectively. As the previous five chapters have explained, in order to do so, managers need to be leaders, models of ethical behavior, effective communicators, political savants, coalition builders, champions of community and economic development, strategic planners, and competent stewards of the community’s resources. Managers need to play all of these roles in an ever-changing community environment. The contemporary condition of fiscal duress for local governments makes government roles particularly challenging.

Municipal and county governments remain the general-purpose public service delivery organizations of the U.S. political system. These governments have the highest levels of interaction with those governed, provide the daily essential services, and face high levels of citizen demand for accountability. Thus, local government agendas are extensive, diverse, and constantly changing. It is important to remember that, especially at the level of local governments, change is normal. Federal and state policies change, regional and local economies fluctuate, technology improves and brings new challenges, citizen needs and wants grow, and political and social values shift.

This chapter examines three aspects of the local government manager’s responsibilities: policy implementation, productivity, and program evaluation. Each is essential for delivering efficient and effective services. First, however, is a discussion of agenda setting and policy formulation.

Agenda setting and policy formulation

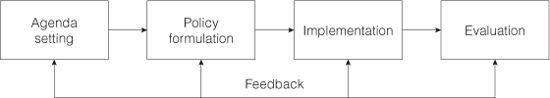

Public policy is “whatever governments choose to do or not to do.”1 Normally, policy making is the responsibility of elected bodies—city councils, county boards, and the like. Local government managers also participate in policy making. The process of creating public policies is usually conceptualized as roughly sequential stages or activities. Thus, in professionally managed local governments, one sees the process (see Figure 6–1) as:

- Agenda setting Process through which issues are brought to the attention of policy makers

- Policy formulation Process of considering options for addressing the issue and adopting a specific course of action

- Implementation Process through which adopted policies are put into action

- Evaluation Assessment of whether or not policies perform as intended; also provides information on how to modify or improve policies.

These stages of the policy process are analytic constructions that are not always independent, distinct, and phased in the order presented here. Clearly evaluation can be used for formulation and after implementation. Similarly, it is difficult in practice to separate the process of agenda setting from formulation. Historically, the council-manager form of government attempted to separate the roles of the elected body and the manager into, respectively, policy formulators and policy implementers. In practice that distinction has proved to be neither realistic nor appropriate. Policy formulation and implementation overlap; each process informs and affects the other. Instead, it is fruitful to look at the stages of the policy process as structured opportunities to combine the professional expertise of civil servants with citizen involvement, leadership with representative decision making, and experience-based continuity with constructive and politically responsive change.

The remainder of this discussion will emphasize agenda setting and policy formulation; the other stages are addressed in subsequent sections. (Another perspective on these topics appears in Chapter 2.)

Setting the policy agenda

The policy agenda consists of those issues or problems that have come to the attention of the government as requiring scrutiny, deliberation, and some decision regarding action (or possibly inaction). How issues reach the agenda can be a complex process, often involving a constellation of elected officials, interest groups, individual citizens, lobbyists, professional associations, political parties, and others.2 Other levels of government can take actions that bring issues to local government agendas. Mass media also have a role in bringing issues to the public agenda. Although policy analysts disagree regarding the directness of media influence, it is certainly true that selective attention to local issues by the mass media often alerts citizens to new issues for government attention and encourages those who already believe an issue should be addressed. Ultimately, however, elected officials and interest groups usually exercise the greatest influence on the content of the jurisdictional policy agenda.

I feel fortunate to be part of the growth of the community in a place where people are getting things done. I’m [a cog in the wheel and] definitely not the driver.

Bruce Clymer

Policy professionals often distinguish between the systemic agenda and the governmental (or institutional) agenda.3 The systemic agenda is a discussion agenda that includes general issues that receive public attention and discourse, but it typically does not include proposals for specific action. For example, on the systemic agenda one might find discussion of the prevalence of street crime, a decline in tourism, or violence in schools. In contrast, the government or institutional agenda contains proposals for the adoption of particular solutions or goals by the government. Local government managers are most concerned with the governmental policy agenda, which encompasses the issues on which the government will take action.

In the setting of governmental policy agendas, the professional manager usually assumes the role of an informed facilitator. The manager contributes knowledge of the local political, social, and economic context; understanding of government processes and procedures; memory of past and current policies; and interpersonal skills to the discussion. A public manager must be able to communicate articulately with all the actors involved and keep the discussion directed at the issues at hand.

It is a tenet of democracy that when elected officials and professional managers set the policy agenda, they attempt to maximize citizen participation. As informed facilitators, professional managers are expected to anticipate reactions from the community and accurately project levels of support for potential policies or future initiatives. If the manager knows the local political arena well; understands local economic and social forces; and is attuned to community leaders, activists, and media, the manager can exercise political leadership to pursue agendas and policies that might not be popular or salient to the public. Effective managers build networks of professional colleagues and rely on professional political and research sources to anticipate public reaction to ideas and policies and to identify important issues that might not otherwise reach the agenda.

Gatekeeping The process of including or excluding items from the government agenda is called gatekeeping. Although it is sometimes exercised unscrupulously, ethical elected officials and managers practice gatekeeping for three legitimate purposes: to bring order to the local agenda, to group together issues that should be considered together, and to prevent the deliberative body from being overwhelmed by issues. Gatekeeping, therefore, requires expertise in strategic planning and management because of its short-range and long-range strategic management considerations. The manager must explore probable futures for the jurisdiction and alternatives for coping with them; this helps to reduce uncertainty as well as support the process of developing effective contingency plans for meeting identifiable social, economic, natural, and technological threats. Advanced contingency planning reduces the need for stressful and costly crisis management. (See Chapter 4 for more on planning.)

Managing agenda setting The manager’s role in agenda setting demands many skills and activities. Certain issues—employee benefits and compensation, internal budget allocations, and purchasing and contracting decisions—recur on virtually every local government policy agenda. In addition, new agenda items arise from new needs or from demands of citizens, politicians, interest groups, lobbyists, the media, or other participants in the agenda-setting process. New issues are generated by economic and social crises that produce calls to curtail services, initiate services (protection against terrorism), or maintain services in spite of budget shortfalls (education, child care, homeless services). In setting the government agenda, the manager must be able to communicate, set priorities, and identify alternatives.

Some agenda items are introduced with no mention of alternatives, and some are coupled with a single proposed solution or with several possible solutions. Agenda setting thus evolves into policy formulation as alternatives developed by a variety of sources—elected officials, citizens, public managers, lobbyists, interest groups, policy planning organizations, and the like—are brought forward for discussion.

Formulating policy

Regardless of when policy alternatives appear, the different levels of effort, cost, and complexity required for implementation of each alternative are usually examined. Thus, part of policy formulation requires consideration of avenues for implementation, and it is up to the professional manager to design implementation strategies for scrutiny or comparison at the formulation stage. Formulation then evolves into implementation because the strategies scrutinized when formulating a policy are likely to be the same strategies used when that policy is implemented.

Because the way a policy is formulated shapes the way it must be implemented, the more explicit and precise the formulation, the less distortion during implementation. Therefore, as part of policy formulation, the local government manager must perform two important functions.

First, the manager identifies prioritized goals and objectives for the policy or program in terms of available resources (or needed resources) and describes results to be created within a defined time frame. At this stage, goals represent the anticipated long-term results of the policy or program; outputs and outcomes are often described in intervals of five, ten, or twenty-five years of elapsed time. Objectives are more short term, usually specifying outputs and outcomes in a particular quarter or in a given year. This is the beginning of the process of marrying budget with policy.

Second, the manager develops plans for the accomplishment of the goals and objectives, specifying personnel, budget, location, equipment, facilities, and other operational features that will form the road map for implementation. The manager’s ability to produce accurate and detailed plans insures that the costs of the policy or program are correctly established and that it addresses the problem intended.

The construction of action plans to chart the paths by which goals and objectives will be achieved falls to government managers. Often action plans represent the product of systems analyses and take the form of detailed flowcharts that associate time lines with particular tasks. Like the formulation of goals and objectives, action plan development is most successful when participation is broadest. Once action plan frameworks are created, it is necessary to associate administrative rules and procedures with the plan. In this way, formal authority and accountability are assigned, staffing is legitimized, and the stage is set for resources to flow at the policy implementation stage.

Implementation—accomplishing objectives—is a central concern in policy formulation and a fundamental managerial responsibility. If the objectives set during policy formulation are to be accomplished, the policy-making process must include consideration of the problems and processes of implementation. Four managerial activities are basic to accomplishing objectives:

- Assigning responsibilities, delegating authority, and allocating resources

- Using functionally oriented management systems to coordinate organizational resources and performance

- Involving people in productive activity through shared performance targets and work processes and through training and the reinforcement of positive jobrelated behaviors

- Tracking progress toward results through intermediate productivity.

Communication is the essence of these four managerial functions. Taken together, they are designed to maintain an organization-wide exchange of information. Because many traditional government functions are no longer performed directly by government, and this trend is increasing, the discussion of implementation concludes with an examination of alternative delivery systems.

Responsibilities, authority, and resources

Assignment of responsibilities, delegation of authority, and allocation of resources are among the most important of the manager’s activities. They also represent contradictions. Subordinate managers and nonsupervisory personnel need clear job assignments and the authority to carry them out, yet responsibilities often overlap, organizational boundaries blur, and authority is in constant flux. In this complex organizational environment, the manager attempts to create and maintain workable relationships. That effort requires an understanding of organizational structures and processes. It also requires active leadership to balance the twin requirements for stability and change.

Organizational structure Organizations can be structured in many ways, but to keep the inevitable contradictions from resulting in chaos, managers need to draw on both hierarchical and open-systems organizational methods. To assign responsibilities, managers can use two concepts from the traditional hierarchical model as generally workable starting points:

- Specialization and organizational grouping by function (e.g., firefighting, law enforcement, planning) are the most commonly accepted bases for assignment of responsibilities; crime prevention is generally a matter for the police, and wastewater treatment is usually a function of the utility or sanitation department

- Authority needs to be specific to a function and commensurate with responsibilities.

These commonly accepted structural principles facilitate assignment of responsibility. Continuity and stability are usually maintained at the operations level because, in an existing organization, most responsibilities can be assigned on the basis of past practice and experience. The chief administrator does not need to make organizational changes when established routines work reasonably well and new functions readily fit existing patterns.

Often, however, new responsibilities do not fit current patterns. If prevention of crime related to drug use is a priority, for example, that function may need to be assigned to organizational units other than the police; it could be assigned to the health and recreation departments and the schools instead. Wastewater treatment may involve not only several departments of a local government but also relationships among several jurisdictions. Because of such complexities, matrix forms of project management sometimes work better than hierarchical structures. A project structure can be formed for such activities from various parts of the organization on the basis of the skills and expertise needed, regardless of the hierarchy.

There are practical limits on the complexity of matrix forms if the desired outputs and outcomes are to be achieved. Jeffery Pressman and Aaron Wildavsky, who studied policy implementation in Oakland, California, warned that designers of policy need to use the most direct means possible to accomplish their objectives. They noted that “since each required clearance point adds to the probability of stoppage or delay, the number of these points should be minimized wherever possible.” Echoing Woodrow Wilson, they also concluded that policymakers should “pay as much attention to the creation of organizational machinery for executing a program as for launching one.”4 Two practical guides to assigning responsibility and delegating authority, therefore, are: (1) maximize functional expertise, and (2) minimize organizational and administrative complexity.

Allocation and utilization of resources Once policy responsibility is assigned, the manager must see that the resources to perform the job are allocated and utilized. Generally, resource allocation relates to four basic administrative service areas: finances, personnel, plant and equipment, and information. One of the manager’s hardest tasks is to maintain these service areas both as a service to line management and as a control system for general management. For example, in hiring personnel, management control may be enhanced by having a centralized system that standardizes most recruiting and hiring processes in a central personnel office. The line (department) manager, however, may find such a system inhibits the department’s ability to hire good employees. If the system makes it difficult to employ the individuals most suited to doing the department’s work, resources are not being allocated effectively, and service delivery and quality suffer.

Resource utilization—in this example, how personnel actually are used—rests in the hands of the department manager. Resource utilization is monitored in part by the local government manager’s evaluation of service and program delivery, which will be discussed later in this chapter.

We now take a systematic approach to service delivery.… Service delivery is no longer based on who is complaining the most or the loudest. It depends on what is the best use of taxpayers’ money.

Mark Ryckman

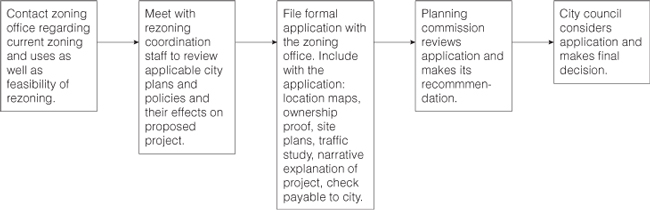

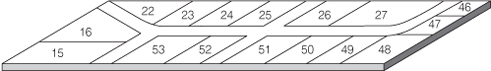

Resource utilization is successful if it accomplishes the desired results. Operational management, also known as results-oriented management, focuses on the outputs and outcomes of management activities. It requires specification, in operational terms, of the activities that fulfill government responsibilities. Thus, operations management might focus on the library’s circulation of books, or responses to requests for information, or the public works department’s maintenance of streets. In addition to the specification of outputs and outcomes, operations management includes planning the processes for achieving them. A flowchart or PERT (program evaluation and review technique) chart depicts the methods and resources used to provide the service. These charts help in making the most efficient use of resources by providing a view of how each step relates to another. They help to avoid overlapping and unneeded steps. Flowcharts also help to determine the time and resources needed to achieve the desired results. In addition, they facilitate identification of changes needed in an organization, procedures, or resources. Figure 6–2 shows a flowchart for processing a rezoning application.

For the local government manager, managing for results should be the overriding goal. To ensure that policies are implemented—and results attained—the manager must coordinate organizational resources and performance. This process is often referred to as functional management.

Functional management

Functional management (one of the components of ICMA’s 18 best practices, see Appendix B) means that the manager must keep an eye on intraorganizational maintenance and development in order to coordinate activities among different units.

Otherwise, competition for resources may become destructive to the organization. In short, attention must be focused on management processes, not simply on final results. In addition, while keeping the overall result in mind, the manager must also ensure that intermediate productivity controls are established for each department so that progress can be monitored and problems identified before they become crises.

Intermediate measures are particularly important in public service delivery. For example, police performance may be measured by the number of arrests made (output). Even though the number of arrests may be less important than reduced criminal activity or an increase in citizens’ feelings of well-being, this intermediate measure provides time and cost comparisons required for important subfunctions and may reveal activities that should be changed or terminated before final results are in. Productivity and performance measurement are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

The functional management system allows organization-wide coordination and integration of activities. In turn, the manager can focus on key issues—cost-benefit trade-offs, contingency responses, and organizational procedures—and providing the resulting information available to others.

The police department, for example, may want to know the relative cost and effectiveness of foot patrols versus bicycle patrols. In addition, it needs to know how well each would respond to an emergency and what the procedures should be for deploying patrols to emergencies. The answers to all these questions are critical to effective coordination and integration of the department’s efforts.

Coordination and integration depend on agreed work rules and performance targets. If they are not established through managerial leadership, they emerge through practice and become binding in fact. These rules must be related to function and kept up to date. They should be guides to behavior rather than limits on action, and they should be kept to the minimum necessary to achieve desired results. On occasion, explicit rules to establish limits on behavior may be required, often to meet legal or technical requirements.

Performance targets

Performance targets for work groups help supervisors improve service delivery (see the performance measures for Knightdale, North Carolina, on page 160). When individuals have performance targets, they may be useful indicators of the need for training, motivation, or discipline. Performance targets may also be used as a basis for reward, although this practice can result in counterproductive employee behavior, and it limits a manager’s discretionary use of authority. Unions typically seek to control performance when quantified work standards are applied to individuals for compensation purposes; unionized workers may tend to work to the rules, becoming relatively rigid and inclined to contest management’s decisions.5

Work process design Work processes in direct public service delivery are usually defined by those who perform the work. Internal processes may be designed more uniformly by management, which sees the needs of the whole organization. In either case, three factors must be considered in establishing work processes:

- Governmental functions

- Workers and their skills and needs

- People served or affected by the activity.

Managers generally should focus on work modules and work groups rather than on discrete units of work and individual workers. In short, as with performance targets, work processes need to be considered from the perspective of functional organizational management, not individual employee control.

Knightdale, North Carolina, finance department performance measures and workload indicator results

Note to original table: Some data for the column, FY 2000 actual, did not meet target this year. The finance department installed new software for privilege licenses, all financial operations, and the utility billing process. Although the new software installation has been completed, the new system did cause some delays in our normal operations, and therefore staff did not meet all targets.

For results-oriented functional management to succeed, managers need to pay careful attention to how they organize for implementation of policies. Traditional theory assumes that the manager informs subordinates of what needs to be done and subordinates carry out the task because of the authority of the manager. Contemporary managers recognize that those who are responsible for achieving results should participate in deciding how to achieve them. Ultimately, the local government manager has the responsibility for results, but, in reality, local government employees share this responsibility.

Sharing authority with employees Various forms of participative management attempt to engage members of the work organization in planning for attaining results.

Team management In team management, parameters are established and a team representing all the units involved in the service or program are brought together to work on planning and organization. Typically, the team or task force has a specific objective in mind, and often a time line is established as well. The advantages of the team approach are that multiple perspectives are likely to emerge and the needs of various parts of the organization are considered in working toward objectives. Redundant efforts and counterproductive steps can be avoided. It is important that the expectations of the group be clearly defined; if they are not, the team may spend a lot of time in meetings that serve no useful purpose.

Project management Project management is similar to the team approach, but it usually focuses on a specific problem or project. Again, it brings representatives from various parts of the organization together to work toward accomplishment of some task. Project management is particularly effective for programs involving several units of the organization.

Quality management Another approach to involving people in planning for the achievement of results is quality management, or total quality management (TQM), a system adapted from the manufacturing sector for use in the public sector, with some good results. A major concern of quality management is the process for ensuring quality. Traditionally, evaluation techniques focus on the results or end service product. In the quality management approach, evaluation is continuous; this means that workers examine their activities to identify problems along the way instead of waiting until an activity is complete. Problems can be detected early and corrections made. This approach saves resources by reducing defects—the goal is zero defects—in products or services and by reducing time by lessening the need to go back and find out what went wrong.

An additional benefit of this approach is that the whole organization is brought into the process, and employees develop a stronger commitment to producing services of high quality. Productivity is likely to improve, and the people served are likely to perceive more interest in their concerns. Employees of the government are empowered if the manager is willing to give up some control and accept the full participation of subordinates in decision making and service delivery processes.

Empowerment also requires the manager to provide people the tools to work effectively. The most important of these tools are training and development. In addition, specific skills are often necessary for analyzing the work process and detecting errors or problems. In most quality management approaches, statistical process-control techniques—used to measure and correct variations in service level or quality—are very important. There also must be team training to focus on quality improvement from a group perspective.

There are many ways for management and labor to relate to one another. Some ways actually build a positive work environment that, in turn, contributes to the effective delivery of local government services. Others that are based upon distrust, enmity, and disagreement, however, injure the work environment and derail service delivery.

James Flynt

Learning organization model The learning organization concept also has been used by local government managers as a way of adapting their organizations to the ever-changing environment. Learning organizations gain information from their environments and use the information to make internal changes, thus affecting the way the organization acts.6 Local government managers have used this model to help adapt to citizen demands for better services without raising taxes. Learning organizations constantly reinvent themselves to better serve their citizens.

Balanced scorecard The balanced scorecard management system builds on many other management approaches such as continuous improvement, employee empowerment, and measurement-based management and feedback.7 The balanced scorecard provides continuous feedback about the internal organizational processes to allow continuous improvement in performance and outcomes. It focuses on four perspectives: learning and growth, business process, customer, and financial.

Checkpoints for avoiding the traps that can damage your TQM process

|

Trap 1: Short-term focus |

Believe that TQM is a long-term journey, not a destination, and add a sense of urgency |

|

Trap 2: The closed kimono |

Don’t place blame. Find fame when your employees bring quality problems out into the open |

|

Trap 3: Quality improvement equals staff reduction |

If quality improvement can result in a reduced staffing level, utilize attrition rather than termination |

|

Trap 4: A green eyeshade only attitude |

Believe that improved customer satisfaction will bring great benefits. Don’t look only at the dollars and decimal points |

|

Trap 5: Delegation |

Total quality management leadership is too important to delegate |

|

Trap 6: Ignoring the 85/15 concept |

Believe that management must be involved in order to resolve 85 percent of your quality problems. Total quality management is not a “fix the worker” program |

|

Trap 7: QI teams are the only way to achieve improvements |

Use QI teams extensively, but supplement and complement them with other continuous improvement strategies. Minimal and selected use of quick-hit strategies is okay, but be careful |

|

Trap 8: Training: Too little, too soon |

Provide just-in-time training |

|

Trap 9: Formal training only |

Build a continuous learning environment |

|

Trap 10: Solving world hunger |

Break large issues down to those more solvable problems that can make the greatest difference |

|

Trap 11: Lack of focus |

Focus QI efforts on the key goals and CSFs of the company in order to advance more quickly toward your vision |

|

Trap 12: A separate structure |

Build a parallel quality organization, not a separate one |

|

Trap 13: The quality department |

Don’t make the quality unit accountable for quality either implicitly or explicitly. Keep the unit small—an internal consulting staff group |

|

Trap 14: Putting the test site on a pedestal |

Showcase the test site carefully. Don’t flaunt it or shove it down people’s throats |

|

Trap 15: Researching customers’ satisfaction |

Don’t just check on how you are doing in the eyes of the customer. Check to see where you should be going in order to meet customers’ needs |

|

Trap 16: The split personality |

Practice what you preach in order to shape the desired culture; what gets measured and rewarded gets done |

Tracking progress

Another important aspect of policy implementation, for the manager and for department heads, is tracking progress by means of intermediate productivity measures that indicate, for example, the level of recreational services in a given neighborhood. Automated information systems can help if they are oriented to the needs of central, departmental, and supervisory management. But relatively simple paper and oral reporting systems may serve just as well. For example, a calendar marked with target dates may serve adequately to track some timetables.

Tracking activities and results must be a sustained managerial activity—regular, but not merely routine. Periodic reports are a classic monitoring device. Some audits may need to be randomly scheduled and others selectively scheduled. An apparently spontaneous visit by the manager to an operating department can serve a constructive purpose, particularly when it is timed to highlight an important accomplishment, such as a significant increase in productivity.

Monitoring must be visible except in rare instances, such as investigations of theft, when security or privacy rights are involved. Whenever possible, the information gained from monitoring should be open to all concerned managers. Monitoring can serve as a positive organizational management mechanism rather than as a negative control if it is used to encourage employees by calling attention to their accomplishments and helping them identify areas for improvement.

Productivity Productivity is defined in economics as the efficiency with which output is produced by the resources used, and it is usually measured as the ratio of outputs to inputs. To focus on effectiveness as well as efficiency, a broader definition is more commonly used in the public sector: the transformation of inputs into desired outcomes. Productivity improvement efforts in government, then, generally include actions to improve policies and services as well as operating efficiency.

A variety of productivity indicators exist: efficiency, effectiveness, responsiveness, quality, timeliness, and cost. Productivity indicators and the information they yield are useful only if they are employed to provide excellent public services, reduce costs, and make improvements when possible.

Productivity applied to investment of financial resources is a related concern. In the current economic environment, local government managers must give the returns on financial investment the same scrutiny as investments in service delivery and support services.

Three approaches to productivity improvement have been successful in the public and private sectors:

- Investment in capital resources and technology

- Strengthened management and work redesign

- Workforce improvement—working smarter and harder.

The second and third approaches relate primarily to improving internal management, which was discussed in the previous chapter. This chapter therefore discusses only investment in capital resources and technology; in addition it explores ways of overcoming obstacles to productivity improvement.

Use of technology in productivity improvement The greatest increases in output generally have resulted from investments in capital resources (plant and equipment, for example) that make use of state-of-the-art technologies. In fact, in the discipline of economics, the prescription for improved productivity is greater technological efficiency in combining human, natural, and capital resources.

Five interrelated aspects of investment merit the attention of top managers:

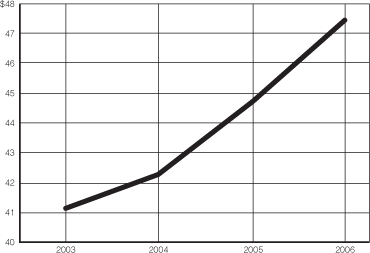

The relation of investment to labor costs Investment in scientific and technological advances and capital resources, along with readily available energy resources, has resulted in large increases in worker productivity. During the 40 years before the extended decline in improvement of productivity that began in the United States in 1968, output per worker increased an average of 3 percent per year, making possible large increases in worker compensation even in the fields outside those responsible for the increased output. Since 1968, the rate of productivity growth has fluctuated. In 1980, it reached its low point and then improved until 1986, when it began declining through 1988. In 1989–1990, the growth rate increased. From 1991 to 1999, the rate of productivity growth again declined. Since 2000, there has been an actual decrease in productivity. The decline in productivity growth, combined with higher labor costs, created incentives for further investment in labor-saving technology. Historically, local governments have been extremely labor intensive, with high workforce costs. The desire for a reduction in labor costs is a strong incentive for introducing technology. Effects on service quality and levels need to be carefully monitored.

Changes in services and public expectations resulting from technological advances Investment typically results in new products and services as well as new technologies for more efficient production of existing products and services. In the private sector, new-product development is often preceded by market research to identify or change consumer demand. Traditionally, little comparable activity occurred in government. Local governments tended to focus only on production of existing services. Today’s citizen surveys and other instruments help identify citizen demand and facilitate government’s response. In addition, the greater involvement of citizens and groups in policy making helps educate them about the limits of government’s ability to provide services. Thus, citizen demand changes as well.

Technological exchange and its impact on organizations The usefulness of technology depends on organization size, structure, processes, and external connections. Some governments are too small to profit from some technologies. It makes no sense to acquire firefighting equipment for high-rise structures, for example, in a jurisdiction that has no buildings over three stories high. Experiences of other jurisdictions may or may not apply in a particular community; technological exchange must be evaluated case by case. Nevertheless, as a general rule, experience supports technological exchange and even the shared use of equipment to improve public service and reduce costs.8

Use of information technology in decision making The technology involved in a geographic information system (GIS) is just one example of how modern integrated computer software and data warehousing facilitate management decision making and effective delivery of services.9 AGIS (Figure 6–3) links many different types of data that pertain to a particular location or area. For example, when a building permit is requested, the GIS can bring up data about the entire infrastructure of the proposed area, types of buildings and businesses, crime rates, traffic patterns, and virtually anything else relevant to the decision. The public works department of Grand Rapids, Michigan, uses a system that permits the staff to map and log work on citizen requests and send an automatic response to the citizen when the work is done. The system combines GIS with mobile responders in the field. Systems like this save an immense amount of time and provide managers with a wealth of data to inform decision making.

Fairfax County, Virginia, developed a citizen relationship management (CRM) program that aggregates and disseminates information to all affected parties. By computerizing information on all county program activities, citizen complaints, and follow-up, the county can track its policies and their effects. Managers and decision makers have complete and accurate information on which to base their decisions and actions. Denise Souder, in Public Management, wrote, “A rising intolerance for system failure or for unreliable data is driving many local governments to change the way they do things.”10

Automated budgeting systems provide similar advantages by linking information systems to allow sharing of data to improve decision making.11 Automated budgeting enhances the processes of developing, preparing, analyzing, and evaluating budget requests. It also is used for developing budget recommendations and allocations and to control use of appropriated monies. Other automated financial management systems are available to streamline payroll, preparation of financial statements, compliance with appropriations and policy, and maintenance of records (see also Chapter 5).

Figure 6–3 Database layering concept from Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky, GIS

Political/Administrative Districts

Zoning

Utilities

Parcels

Planimetric Features

State Plane Reference Grid

Topographic Lines

Geodetic/Survey Control

Cost savings and investment Investments in equipment and technology are usually expected to yield cost savings. Savings resulting from investment in equipment should at least amortize outlays by the end of its useful life. If an investment is expected to improve productivity by reducing costs, then savings should yield a net return on the investment (including an amount equal to or exceeding the interest). However, improving services is also part of productivity improvement. Among internal service improvements are such things as raising the accuracy of revenue forecasts, reducing the average time to clear financial transfers, and reducing the cost to repair municipal vehicles. Citizens appreciate improvements in response times for addressing utility connections, increased cleanliness of streets and parks, speed in the repair of reported potholes, and reduced waiting time for purchasing permits. Improvements in these productivity measures mean increased citizen satisfaction with local government.

Overcoming obstacles to productivity improvement With help from employees in identifying four common obstacles to improvement in local government, managers can take actions to overcome them:

Organizational constraints Organizational constraints in government may derive from political and legal frameworks that cannot be easily changed. Often, however, the limiting factors are structural and procedural and, therefore, are amenable to change by management. A manager must strike a balance between the one extreme of centralization and uniform prescription of rules and procedures and the other extreme of dispersion of responsibility and differentiation of processes to suit every individual’s wish. Current information technology makes it easier to exercise control without resorting to rigid and unchanging procedures. In addition, the manager can bring legal obstacles to the attention of elected officials for revision.

Resource limits The manager must inform citizens and elected officials when resources limit policy, service, and productivity improvement. Cost-benefit assessment may show that reallocation of money, people, equipment, buildings, or other resources will improve productivity. When resource constraints are a major concern, local governments commonly tap into their reserves, increase fees for services, reduce staff, or reduce spending on infrastructure and maintenance.12

Information deficiencies Information is one resource whose deficiencies are most subject to managerial correction. Three practical questions may help identify and eliminate barriers: Which data and analyses are needed? How is the information disseminated? How is it used? The department of planning in Lynnwood, Washington, has improved services for the public by integrating its geographic information and document imaging systems. The document imaging system allows the city to file information digitally instead of on paper. The electronic integration of information results in faster service for the citizen, with more complete information. Investment in information technology is currently of major importance in improving collection and dissemination of information (see Figure 6–4).

Disincentives Although attention is often given to motivation and incentives, sometimes policy makers make productivity improvements in ways that alienate people; for example, they impose across-the-board budget cuts for both productive economizers and unproductive spendthrifts. Communication with employees is of utmost importance in identifying disincentives.

Government efficiency is another goal. There has been a clear transition from the traditional status quo to an openness to change amongst the city staff. It has been an interesting challenge, and I am heartened by the staff’s responsiveness and willingness to make this transition. On my business cards are three words: “open,” “agile,” and “purposeful.” To lead an organization of this size, I think it is essential that we are receptive to new ideas and not defensive.

Craig Malin

Alternative delivery systems

Although public services are typically delivered directly by local government, numerous alternative delivery systems have been used for years, ranging from food and recreation service franchises to virtually full-scale government by contract, as when urban counties provide almost all services to their small communities. During times of retrenchment, interest in alternative delivery systems increases as officials seek to reduce costs and offer different levels of service on the basis of citizens’ willingness to pay.

When choosing alternative service delivery systems, local governments need to develop criteria for evaluating them. The criteria generally include

- Cost of service

- Financial costs to citizens

- Choices available to service users

- Quality and effectiveness of the service

- Distribution of services in the community

- Service continuity

- Feasibility and ease of implementation

- Citizen satisfaction

- Potential overall impact.

Alternative service delivery systems take many forms, described below and also in Chapter 7.

Privatization Privatization of services, including contracting out and franchising, has become common in local government. Contracting out is the purchase of services from another government or private firm, for-profit or nonprofit. All or only a portion of a service may be involved. Small governments may obtain specialized services and gain advantages of scale by purchasing services. For similar reasons, a government may choose to sell services to neighboring governments. For example, urban county governments often sell computer, law enforcement, and fire services to local municipalities. Contracting out also allows the purchaser to take advantage of market competition to gain efficiency and cut costs.

Contracted services are usually those that are easily defined. Solid-waste collection and water services are easily defined, and both are often contracted privately. Day care, drug treatment, and transportation of disabled people are commonly provided by specialized contractors. Law enforcement, however, is more complex and rarely contracted out except to another general-purpose government.

Like special services contracts, franchises have been used for decades by local government. Franchises are typically awarded to exclusive or nonexclusive providers through competitive or negotiated bidding. Individual citizens usually pay directly for the service, such as for the food served at a sports arena owned by the local government or for an ambulance ride to a hospital. Governments generally charge a percentage of gross or net income as a franchise fee.

Joint ventures Partnerships between local governments and the private sector have long been common, and they range from relatively modest programs to upgrade downtown storefronts to construction of large public facilities like airports and sports arenas. Usually the local government subsidizes the venture through tax incentives or the development of parking facilities or other public amenities. More recently, joint ventures to upgrade a community’s telecommunications infrastructure are becoming common. For example, South Sioux City, Nebraska, partnered with the local cable company to build a fiber-optic network that provides high-speed Internet access to the city, to residents, and to businesses.

Local communities bank on being repaid through taxes on the earnings generated by increased employment and other multiplier effects of joint ventures. Sophisticated citizens, however, may question whether growth compensates for the changes in the environment and character of the community. The local government manager is challenged to accommodate conflicting perspectives on development; this challenge is discussed in Chapter 4.

Intergovernmental contracts and agreements Local governments have a long tradition of engaging in intergovernmental agreements and contracts, although some states traditionally restrict them. In 1988, the city of Corvallis, Oregon, contracted with the county for repairs to its vehicle fleet, expecting to save as much as 20 percent on maintenance. Fire service is frequently provided under contract or by agreement by a large jurisdiction to smaller communities, and sometimes several units of government get together to provide service such as mass transportation when the need encompasses a large area and requires integration of service. Urban counties in California and Florida often provide municipal services to small communities via contracts or agreements.

Volunteer activity Volunteer and self-help activity are important alternatives to direct public service delivery. For example, many sheriff’s departments and fire departments depend heavily on volunteers. Josephine County, Oregon, uses volunteers for reception desks and filing in its library system and many of its county departments. Some cities, like Virginia Beach, Virginia, have developed robust volunteer programs that fill a wide variety of needs throughout the government and community.

Self-help includes neighborhood watch programs, neighborhood cleanup, and mutual assistance to mentally or physically disabled and elderly residents. Henrico County, Virginia, for example, organized a volunteer program in which seniors help one another, thereby reducing their dependence on the local government.

Volunteer and self-help programs reduce the demand for direct service by local governments, but they have other ramifications as well. For the local government manager, these efforts often bring new actors into the management and policy-making process. Neighborhood groups participate in the policy-making process, and local government managers need to be able to deal with them effectively, as discussed in Chapter 2. In addition, risk management issues may arise, and the manager should consider local government liability when deciding on the level of official responsibility to be assumed by volunteers.

The relationship between policy formulation and implementation

The policy implementation process is complex and involves the participation of many actors. The traditional assumption in public administration was that elected officials make policy and managers implement it, but that assumption no longer holds. If implementation is to be effective, it must be considered as part of the policy-making process. Plans for implementation and the policy’s cost as well as benefits must be considered while policy is being made. Otherwise, the policy that is developed may not be realistic. Once developed, the policy depends on the involvement of the whole management team to be effective. Therefore, the effective local government manager must ensure that the management team assumes its responsibility for policy implementation. In addition, it is important to involve citizens and groups affected by the policy.

Evaluation is the collection and analysis of information regarding the efficiency, economy, and effectiveness of programs and organizations. The types of information collected, the types of analysis, and the uses of the knowledge produced vary, but the twin objectives of evaluation remain the same: assessing goal achievement and improving function. In a local government setting, the knowledge generated by evaluation may be used by managers and elected officials to accomplish at least four important tasks:

- Allocate scarce organizational resources

- Determine which goals are being met and which programs are performing as intended

- Identify specific reasons for successes and failures

- Adjust programs for additional improvement or terminate ineffective programs.

It is through these activities that managers monitor and innovate to insure that their program or department adapts to changes in internal and external environments and remains responsive to political forces and public needs.

Departmental vs. program evaluation

The evaluation of departments is generally considered separately from the assessment of programs. Departments are part of the organization of government itself and, consequently, are relatively permanent. They typically exist to execute service functions that remain relatively constant over time—for example, police departments, fire departments, water and wastewater, public works, and transportation. Programs, on the other hand, are subject to the ongoing public policy process and can change from year to year. Programs are often special or innovative means of accomplishing some particular goal or delivering a specific service. For example, many municipal fire departments run programs to deliver crisis counseling to victims of fires or medical emergencies.

Consequently, the options available to the decision maker as a result of an evaluation are different for departments and programs. For example, it is unlikely that an ineffective police department will be dissolved, but a counseling program that fails to deliver quality services might be discontinued. Another difference is that departmental evaluations tend to put more emphasis on changes in performance over time. The methodology and tools for conducting evaluation are largely the same for departments or programs.

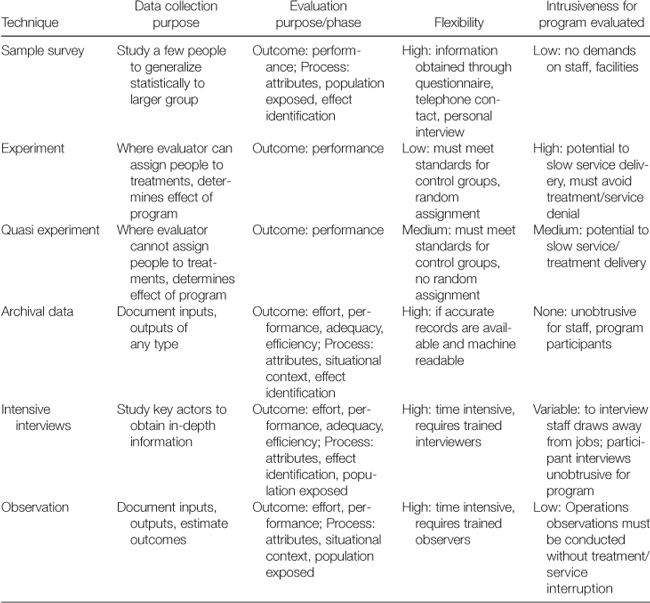

Types of evaluation

Program evaluation is the systematic assessment of a program’s or a department’s goal achievement. Usually there is a longitudinal concern in the assessment, but a typical evaluation is conducted at one point in time to determine goal achievement over a defined prior period. Performance audits are a type of program evaluation, and sometimes it is implied that departments are subject to audits and programs are subject to evaluations. According to the U.S. General Accounting Office, a performance audit determines the economy, efficiency, and effectiveness of government entities, including their compliance with relevant laws and regulations.13 Program evaluation, on the other hand, is the use of social science research methods to examine and document the effectiveness of social intervention programs.14 The significant difference between the two types of evaluation seems to rest with professional disciplines of investigators (auditors tend to be accountants, evaluators tend to be social scientists), the scope of the research (audits tend to emphasize effectiveness, which is defined financially), and certifications available to investigators (auditors tend to be certified public accountants or certified internal auditors, but there is no certified program evaluator program).15 Yet it is clear that both program evaluation and performance audits may address similar issues.

Data collection options for program evaluation

A third type of evaluation, policy evaluation or policy analysis, is the assessment of actual or probable impacts (outputs and outcomes) of a given policy.16 Such analyses can be undertaken before implementation (dealing with probable products) or after (dealing with observed products); the analyses identify the likelihood of achieving intended effects, the production of unintended effects, costing features, and projected political and administrative impacts.

Clearly, the differences among performance audit, program evaluation, and policy analysis are a matter of focus and degree. Historically, performance audit is associated with financial and effectiveness assessments; policy analysis is usually narrowly focused on particular policies (though perhaps with multiple goals); and program evaluation is seen as a comprehensive assessment that may be directed by managers or elected officials. The similar thread is that all three are assessments (although foci and purpose may vary) that yield important managerial information. In the following discussion, the term “program evaluation” is used for all types of evaluation.

An evaluation agreement

The reasons for an evaluation—managerial good practice, jurisdictional tradition, or legislative or regulatory requirement (including sunset reviews)—may impact the scope, nature, and frequency of assessment. It is common practice to define an evaluation in a memorandum of understanding, in a statement of scope of work, or perhaps in legislation (for example, a sunset evaluation). This is to the benefit of the manager whose department or program is being evaluated and to the manager directing the evaluation. The formal written agreement should specify whether a department or a program is being scrutinized. A typical agreement addresses six issues: who will evaluate, the scope of evaluation, the type of access to people and records, the cost, the time frame, and important topics for the final report.

Performance measurement and management information systems

An important tool of evaluation, performance measurement is “the ongoing monitoring and reporting of accomplishments, particularly progress toward pre-established goals” that is the responsibility of government managers and department heads.17

Program evaluation and performance audits document the process and outcomes of a particular program or department at a specific point in time. In contrast, performance measurement is an ongoing program that includes devising specific performance measures (or performance indicators) and continuously collecting information regarding these measures (see the chart on page 172 on fire service measures in Phoenix) that can be incorporated into managerial decisions regarding performance.18 For example, a police department may collect information on the number of false-arrest lawsuits and their outcomes as one dimension for assessing the utility of existing written guidance on arrest procedures.

In the context just described, performance measurement is part of a management information system: the continual effort of managers to examine the efficiency, effectiveness, or economy of the services delivered by their program or department. Individual performance measures (e.g., number of uncontested arrests) can be used in a program evaluation, but performance measurement is a process separate from an evaluation.

A management information system may involve many different types of measures, some aimed at performance (outcomes and impacts), and others aimed at effort, process, efficiency, and similar dimensions. Montgomery County, Maryland, for example, uses a three-pronged approach of internal auditors, office of legislative oversight, and an inspector general to audit funds, performance, and fraud and waste, respectively. Although the concept of performance measurement is very popular among elected officials, program evaluators, and some managers,19 its utility hinges upon the extent to which particular measures are actually used to accomplish managerial tasks and the degree to which it is integrated into a system that also accounts for aspects of program and department operation that are not related to performance.

|

Performance measures in fire services, Phoenix, Arizona, fire department |

|

|

Function |

Sample performance measures |

|

Emergency medical services |

Percentage cardiac responses less than 4 minutes Percentage paramedic recertification tests passed on first attempt Number of paramedic continuing education opportunities taught this quarter Number of equipment failures in the field this quarter |

|

Emergency transportation services |

Percentage of transportation fees collected Percentage of trauma transports reaching hospital in 5 minutes Average out-of-service time per ambulance per call by patient chief complaint Percentage of Code 3 trips that result in vehicular collision |

|

Special operations: hazardous materials |

Percentage of hazardous materials technician re-certification tests passed on first attempt Percentage of hazardous materials incident responses with responder lost-time injury Number of hazardous incident refresher classes taught this quarter Percentage of hazardous materials incident responses with agent identification in under 5 minutes |

|

Fire suppression |

Percentage fire incidents with initial response of first due crew in 4 minutes or less Percentage 3-1 fire incidents with command officer arrival 4 minutes or less Percentage fire incidents with damage confined to two rooms or less Percentage fire incidents with all-clear benchmark in 5 minutes or less |

|

Fire prevention |

Percentage of new construction plan reviews completed in 72 hours Number of new construction inspections completed per inspector by residential/commercial Percentage of schools in jurisdiction participating in urban fire safety instruction programs Number of public events staged/participated in for fire education this quarter |

The practice of performance measurement has its pitfalls.20 Perrin has argued that well-chosen performance measures are useful for “monitoring performance, raising questions and identifying problems requiring management attention,” but not for “assessing outcomes, determining future directions or for resource allocation.” Perrin elaborates a variety of flaws in creating and using performance indicators, including serious issues like performance manipulation and goal displacement: “In Poland under communism, the performance of furniture factories was measured in tons of furniture shipped. As a result, Poland now has the heaviest furniture on the planet.”21 Perrin’s complaint focuses not just on the way indicators are devised but also on the way they are used. Even proponents of performance measurement agree that, in the absence of a systematic framework for collating, evaluating, and examining performance indicators, the collection of data on the measures is not useful.22

Having good performance measures makes it easier to defend our resource allocations.

Don Gloo

In government, performance measurement is quickly becoming a fact of life. The provisions of the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 require that federal agencies collect and report performance measures on programs. Thirty states have enacted legislation requiring that agencies engage in at least some level of performance measurement.23 Cities and counties commonly practice performance measurement,24 and as of early 2004, more than 100 local governments participate in ICMA’s Center for Performance Measurement, a consortium formed to develop and benchmark performance measures for a wide variety of local government functions.

Performance indicators

Performance indicators themselves are multipurpose and can be used in the context of management information systems or program evaluation.25 The creation of performance indicators—even with a management information system in place—requires careful attention. The guidelines below provide standard guidance for choosing and using performance indicators.

Guidelines for performance indicators

- Target what is meaningful within the context of the program or department. Involve managers, employees, and stakeholders (including citizens) in the process of identifying key indicators of performance and how they will be defined for the data collection process. The goal is to choose indicators that are less subject to misinterpretation or misuse, and more likely to reflect genuinely meaningful outcomes or impacts of the program or department.

- Identify and choose indicators over which the program or department staff exerts direct control. This goes far to ensure that changes in performance are reflected in changes in the level of the indicator. General indicators that are affected by the operation of many programs or people make it difficult to accurately attribute responsibility for changes in performance.

- Test selected indicators before the assessments. Use a trial implementation of information collection and then get feedback from those collecting data and those responsible for the operations that generate the data. Review the information, its interpretation, and the collection process for accuracy, effectiveness, and meaningfulness.

- Reexamine, revise, and update performance indicators regularly. As circumstances, missions, and organizational arrangements evolve, indicators must also evolve; otherwise information will be gathered that does not measure or reflect critical operations. The review process should be widely based, involving managers, employees, and stakeholders.

- Place outcome information in perspective. Finding that a performance indicator is low does not explain why or how performance may have changed. Further investigation of matters unconnected to performance—such as budget, process, personnel changes—is essential to diagnose organizational challenges and improve productivity.

Performance indicators tend to reflect output or outcomes. Measuring the quality of output and outcome may require, for example, going outside the organization or program to get citizens’ subjective rating of the quality of services delivered by that department. It is difficult to capture process information with performance indicators, but the interpretation of outcomes and outputs may require process data. Awareness of the limitations of performance measurement is key; performance indicators cannot answer questions they were not designed to answer.

Performance measurement may lead to increased workforce productivity, but it is probably more important as an instrument for the examination and improvement of managerial decision making. By focusing on which tasks are to be performed or services are to be delivered, the manager can systematically identify appropriate strategies, tactics, and processes and allocate resources. The decision-making process is improved to the extent that attention is given to what is to be accomplished and how that accomplishment may be measured. Service is also improved. Citizens and clients benefit because they receive better service and are more able to hold government accountable.

Reasons for evaluation

Program evaluations may be undertaken for a variety of reasons and ordered by a variety of actors. Thus, an assessment may be required by legislation that establishes a program or a department or by administrative rules. In municipalities with internal audit departments, the manager’s office may require that every department or some subset of a department’s programs be evaluated regularly—perhaps every five years. Program or department directors may order an evaluation as a means of examining operations and improving productivity. Evaluations may be required as a condition of accepting state or federal funding. For example, when the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development provides municipalities with funds for safety and drug abuse programs in public housing projects, it requires that the programs be externally evaluated each year.

The auspices under which a program or department is evaluated usually affect the focus and possible outcomes of an evaluation. Sunset evaluations, for example, focus on determining the degree of goal achievement and may result in closure of the department or program if achievement is inadequate. On the other hand, evaluations commissioned by program managers balance emphasis between outcomes and process and typically aim at identifying tactics for improving program operation regardless of the level of goal achievement.

From a practical standpoint, it makes no sense to evaluate before some performance exists to be evaluated. It is important for managers who institute an evaluation of their own program or department to be certain that the conditions for an appropriate evaluation exist: that the program or department has operated long enough, with sufficient resources, to create a structure for achieving goals (or mission) and to generate meaningful outputs. In the technical literature, this is called an evaluability assessment.26 Managers whose programs are evaluated at legislative or regulatory direction, or at the direction of their managers, should make sure that an assessment of evaluability is carried out. Also, any evaluability assessment by an evaluation team should be accompanied by the manager’s own assessment. If the two assessments do not agree, or if the manager’s assessment states that nothing yet exists to evaluate, then the evaluation team, the relevant manager, and those who directed the conduct of the evaluation need to communicate. When there appears to be an inadequate structure for goal accomplishment or inadequate output, the manager of the program or department usually documents the situation and provides an appropriate explanation. In such cases, the evaluation team may be asked to determine how the current state of affairs arose, not to conduct a more standard evaluation.

Emphases in evaluation

Program evaluations may emphasize either process, or outcome, or both.27 Process evaluation, sometimes called formative evaluation, produces information about how or through what mechanisms and structure a program or department operates. Outcome or summative evaluation assesses whether goals have been achieved. Put another way, process evaluation shows how goals are accomplished while outcome evaluation reveals which goals are accomplished, and to what degree. Although outcome evaluation is generally considered critical, most evaluation professionals emphasize the need for balance with regard to process and outcome elements.28 Conducting an outcome evaluation without including process elements can place an evaluator in the position of either knowing a program works and not being able to explain why, or knowing a program does not work but without a clue about how it might be repaired.

Sometimes legislatively required assessments focus on outcome evaluation to the exclusion of concern with process. Sometimes resources do not permit a multifaceted evaluation design. Although such exigencies may require a narrower evaluation, managers of programs or departments that fail outcome evaluations should be aware that corrective action may require compilation of information regarding process.

Outcome or summative evaluation The goal of outcome evaluation is to paint a complete picture of goal achievement in the program or department. A typical picture is composed of four assessments: effort evaluation, performance evaluation, adequacy, and efficiency evaluation. In the broadest sense, these four dimensions are performance standards against which programs or departments might be examined. Each standard is measured in terms of a variety of possible performance indicators.

Process evaluation In large part, the purpose of process evaluation is to aid in the interpretation of results from other phases of a comprehensive evaluation. In particular, information about process offers a meaningful context for understanding performance evaluations. Process elements in an evaluation focus on understanding and documenting the structure, procedures, and mechanisms through which a program produces results. Process evaluations help pinpoint why successes and failures take place and, in so doing, contribute to the prevention of future failures. Furthermore, process evaluations identify and assess unintended impacts of program or department operation. Most process evaluations begin with the creation of a case or process flowchart. Such charts resemble decision trees or fault trees that specify all operations (decision and contact points) associated with the program or department of interest. An effective process evaluation looks at four dimensions of programs or departments: attributes, population served, situational context, and types of effects.

Equity

In evaluations of programs and policies, contemporary local government managers must always incorporate the criterion of equity in addition to the standard concerns of inputs, outputs, and processes. Equity is a challenging concept to apply at the policy level when different groups of citizens require different services to meet their needs. Managers should account in the evaluation process for such differences in needs and characteristics.

Costs and uses of evaluation

The process of evaluation—the use of management information systems, performance measurement, or program evaluation—is a critical source of information for the local government manager, but it can be costly and elaborate. Managers need to examine carefully the costs of evaluation (in dollars, time, and opportunities not pursued) to be sure that they are adequately balanced by the benefits of evaluation. Performance measurement as a day-to-day management approach regularly involves managers, whose time is valuable and limited; hence, the benefits of this approach should be weighed carefully against the cost in terms of time not available to other activities. The uses made of evaluation information largely determine the evaluation’s benefits. Department-level managers may regularly use evaluation information. The manager’s office and elected officials must also make constructive use of evaluation for it to fulfill its primary purposes of improving policies, services, and productivity.

- The chapter, setting the stage for a discussion of program management, describes various aspects of the manager’s involvement in policy making: setting the agenda; gatekeeping; managing agenda setting; and designing plans for implementation that define goals, objectives, and priorities.

- Traditionally, local government managers have had to balance three major concerns in administering public policies: efficiency, effectiveness, and economy. Today, however, equity and ethics are receiving increased emphasis. This chapter examined three dimensions of local government program and service management—implementation, productivity, and program evaluation—to identify ways to address these concerns.

- Communication is essential to the success of managerial efforts to implement policy: through assigning responsibilities and allocating resources; using functional management to coordinate resources and performance throughout the organization; encouraging productivity through performance targets and reinforcement of positive job-related behavior; and tracking progress toward desired results. Quality management, employee empowerment, strategic planning, and productivity measures were examined.

- Alternative delivery systems, privatization, joint ventures, intergovernmental agreements, and volunteer activities are used regularly when local governments choose not to perform traditional government functions directly.

- Local governments have found success in improving productivity through investment in capital resources and state-of-the-art technologies. Rank-and-file workers and supervisors can often identify and eliminate many barriers to productivity, but cannot eliminate the systemic barriers of organizational constraints, resource limits, information deficiencies, and disincentives.

- Evaluation can improve a local government’s decision-making processes, public policy, services, and productivity. The role of evaluation in program and service management, targets of and types of evaluation, costs and uses of evaluation, and several measures of organizational and program performance were presented.

Citywide customer service in Peoria

by Duane Otey

Citizens living in Peoria, Illinois, have long wanted and expected service equal to or exceeding the standards set by top-performing private organizations, so the concept of customer service is not new to the city. Peoria’s managers and employees are encouraged to examine their respective customer service roles regularly and to renew their commitments to the citizens they serve. The city, which is dedicated to ongoing service delivery improvements, offers comprehensive customer service training and consultation assistance to all its employees.

Project objective City administrators want to make further improvements in the way in which service is provided, to raise concern for special populations, and to increase efficiency by tapping into techniques of quality management, empowerment, teamwork, and benchmarking. To do these things, Peoria has partnered with citizens through community-based policing, open-space forums, neighborhood associations, citizens’ training programs, and town-hall meetings. After considering their feedback, the city manager has called for a citywide emphasis on customer service. In response to this directive, we have interviewed staff and council to measure organizational needs and to help formulate the customer service program’s structure. Although each individual had a different point of view, three common concerns emerged. Management should:

- Assess how city staff interacts with citizens.

- Enhance communication skills, as they are key to a successful customer service program.

- Ensure that employees are fully committed to the program.

Research To benefit Peoria’s program, the history of customer service in other local government organizations was researched. As we collected information, the elements of successful programs continued to surface. Although many local governments embrace components of customer service, here is a summary of three communities that have put in place comprehensive programs.

Grand Rapids, Michigan

- Established a customer service focus in all areas of service.

- Established employee teams to offer input.

- Brought in representatives of private businesses to help train staff.

- Insisted that staff go the extra mile in serving others.

- Redesigned city hall to make it less of a rat maze and installed kiosks.

- Offered all employees name tags.

- Published a pocket-size, eight-page, waterproof city service directory for all employees.

- Believed, and believes, that if you give most staff the proper tools, they will do a good job.

Chesapeake, Virginia

- Began the “Year of the Citizen” program in 1991.

- Has established employee focus groups to answer questions like “What frustrates you?” and “How can we improve?”

- Trains new employees yearly.

- Has developed the Customer Satisfaction Depends on Me training handbook, course handouts, and a historic outline of the development of its customer service program.

Phoenix, Arizona

- Has appointed service-representative teams within each department to develop, administer, and evaluate customer service projects. The teams assess points of customer contact, service cycles, service blockages, and service delivery data and recommend improvements.