3

Coping Mechanisms

Billings, Montana, August 1976.

It’s been a year since my summer in Glacier National Park, and I look back at that time with a mixture of joy, confusion, and anger. But not for long. A new chapter in my life is beginning, and I feel excited. My senior year is coming, and in my mind it will be filled with parties, sleepovers, and movies. Memories in the making. Get through this and the gate of life will be open. I will be free! I am partially there already, in the freedom department. Last month Dad, angry with the marriage, took a job in Minot, North Dakota. He’d made no invitation for us to join him. This wasn’t the first time my parents had lived apart; there was the time Mom had left him, taking me with her, in Great Falls. But I think he figured the marriage would be patched up, like it was before. Therefore, he saw his leaving as a separation. Mom saw it as regaining her independence and filed for divorce. That’s why we’re having a garage sale.

Our garage is beneath the house, a sharp ninety-degree turn from the street. Mom never parks in the garage because her Oldsmobile Delta 88 can’t make that turn. So this space has been turned into Dad’s woodworking shop, with shelves added for additional storage. Today, however, it’s turned into a secondhand store. Mom and I have brought our dining room table, our coffee tables, and side tables down the narrow stairs from the main living floor. These will be used to show our “gently used” wares. For more counter space Mom has placed a piece of plywood over two sawhorses. These surfaces will hold, seemingly, every article we own. Mom has taken this garage sale very seriously.

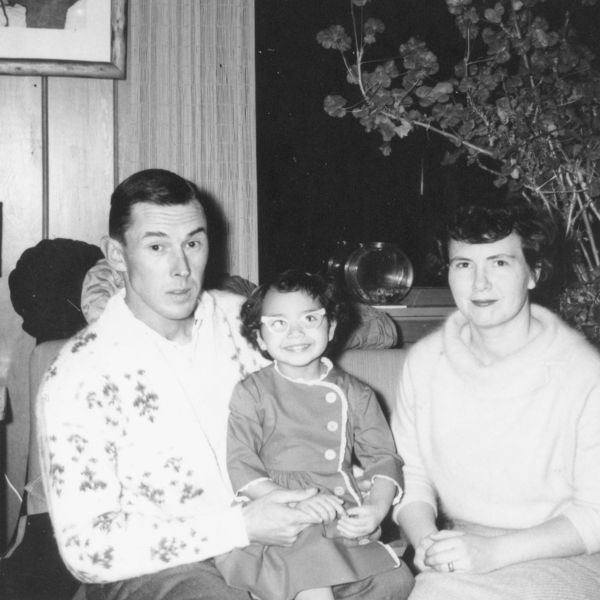

3. Adoptive parents, Jed and Eleanor; and Susan, age three. A family photo. Photo by Jed Devan. Courtesy of the author.

“I hope no early birds show up,” she says, as she carefully writes the item number and the price on tags and checks these against an inventory sheet. “I can’t stand the early birds. They’ll have plenty of time to buy without showing up at six in the morning.” She doesn’t pause in her efficiency. This afternoon her voice is unusually sharp, but I dismiss it, thinking it’s just nerves. Tomorrow her space will be invaded by a hoard of strangers. Handing me a stack of price tags and a pen, she points to a box filled with my childhood: books, toys, and stuffed animals, none of which I want to sell. But what I want is immaterial. “You’re too old for that junk,” she says, waving away my distress. There is no arguing with her.

I fan out my set of Nancy Drew books, published in the late 1950s. Their navy cloth covers are worn and tattered along the edges, signs of the love affairs young girls have for good mysteries. I hold The Secret of the Old Clock to my nose and inhale the musty smell of attics, closets, and boxes garnered through my three moves and countless others by its previous owners. When I place it with the others, my heart is heavy. As if to say good-bye, I touch each gently, placing a sticker with “10 cents” written carefully across it, and turn away, a lump in my throat. Mom’s voice whispers in my mind, Imagine, crying over a book!

These books, among others, are not just material items; they’ve woven themselves around my heart. As an only child, isolated in the rural landscape, they have kept me company on long, solitary days and provided a screen of distraction while my parents quarreled bitterly. I hate saying good-bye.

While I’ve been working on my things, Mom has hung a length of steel pipe, held in place by wires from the ceiling. It is about three feet long and acts like a clothes rod, where shirts and pants and some skirts and dresses are carefully hung on hangers. The only item I don’t want to sell is the umber doeskin vest, velvety soft, constructed from the hide taken during a successful hunting season twenty-some years earlier. Mom had fashioned a beaded design, which sits gracefully above each pocket flap. It will be the first thing people will see. My fingers move gently over the glass beads, and I pull the leather close to my face, drawing in its smell. I’d worn it, just as I wore Mom’s buckskin jacket (which I was able to talk her out of selling), taking pride in their representation of my American Indian heritage. Granted, it is an imagined heritage; I was not raised in an Indian family, nor was I raised in any kind of Native community. But when I slip it on, I feel more “Indian.” I don’t tell anyone this because it sounds ridiculous, but I see it as my heritage nonetheless.

“Why are you getting rid of this?” I ask for the third time, holding the leather gently in my palm.

“I don’t wear it anymore,” she answers, tying yet another tag to another piece of our past.

“But I do,” I argue, unable to keep the pleading out of my voice.

“You’re going to college next year; you don’t need that old thing. Someone else can use it.”

I sulk. Especially when I glance at the price tag: “$12.”

The next morning, within ten minutes of the sale starting, the doeskin vest is purchased by a woman in her twenties, her broad smile indicating she found the deal of the century. By two in the afternoon nearly everything has been purchased. Mom is making fantastic deals in her last-minute negotiations. By three she pulls the garage door shut and goes upstairs to make a late lunch while I clean up. Bored in the silence, I turn the radio dial to a hit station and turn up the volume. Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop Thinking about Tomorrow” blares from the Sony speakers. I sigh as I sweep the floor. Considering this day and the ease with which my life has been carried out the door, tomorrow seems to be the only solid thing I have to think about.

The divorce is finalized three weeks after Mom filed, and Dad is astounded at how fast it was granted. “The judge didn’t even ask me if I wanted it!” he says, confusion filling his voice. Montana, a no-fault state, is filled with domestic violence, drinking, and a lot of spite. The attitude is that those who want out should be allowed to do so. Quickly. So now Mom is single and filing to reclaim her maiden name; she wants nothing to do with Dad.

Tension trickles into every aspect of my life, and I no longer see my dreams of a fun senior year taking place. Mom is abrupt; Dad is absent. I turn down every invitation offered for fear friends will know how really chaotic my life is. One night in the middle of October, chaos takes a new turn, when I walk into the living room to see Mom crouched near one of the stereo speakers. “What are you trying to tell me?” she asks the speaker, then she turns her head so she can catch whatever reply might return. I have no idea what that reply might contain. All I hear is the weather report. It is calling for snow.

That night I lay in bed and wonder, how did she move from a frantic garage sale to this? I rake my memory, but nothing stands out. I can’t map the change in her behavior, one gentle step leading to another. Or perhaps I don’t want to map the change because it might undermine my belief that never once, in my fifteen years being raised by her, has Mom ever given me reason to doubt her actions. She’s dedicated her life to me, her daughter. I was never her adopted daughter. She signed me up for all the appropriate cultural lessons: music, piano, voice, and dance—both ballet and jazz. She made sure I had access to all the activities she felt kids should be part of: Girl Scouts, 4-H, Pep Club, band, orchestra, and choir. She felt the right friends to be important, so she’d drive me sometimes fifty miles round-trip to girls’ houses to encourage friendships. But more than anything, she protected me.

When I was sixteen Mom and I went to a small mall in Missoula, Montana, that contained a variety of retail shops. I wanted to go to the clothing store; Mom wanted to go next door. She’d meet me at the clothing store when she was done. Alone I moved around and between the racks, pushing clothes apart to get a better look, moving on to the next and the next and the next. I leisurely explored the bins, holding up T-shirts that I thought might be fun. But I felt the manager’s eyes on me: she was predator and I was prey. I looked at her, her mouth turned down, her eyes unblinking. That changed in a moment when another woman came to the register, garment in hand. She was all smiles and bright talk. In fact, over the twenty minutes or so I was there, she seemed to have a smile for everyone except for me. Every time I looked up, she was staring at me. At some point she muttered something about dirty Indians, and I felt my face grow hot. I didn’t know what to do, so I stood back, away from the clothes, near the door, and waited for Mom. When she arrived, I held a pair of jeans several sizes too large and pleaded with her just to buy them. I could alter them when we got back to Billings, I assured her. I just wanted her to help me escape the oppressive heat of hatred that filtered around me. I didn’t want her to see how inferior I was. Although Mom had tried to raise me to stand up for myself, this woman behind the cash register held more power and more authority; I couldn’t stand up against that. I had no self-confidence. I felt there was something wrong with me.

When I was six, Mom and I lay side by side on our stomachs looking for four-leaf clovers in the lawn. We rested on our forearms while our fingers combed through the end-of-June grass, dark green and strong against our fingers. My brown arm lay against her porcelain one, and I admired its myriad of freckles. “You have such pretty skin,” I said. “I wish I had your skin.”

She looked at me, her eyes wide, while she wrinkled her nose and pulled her brows playfully together. “This old, white skin? No, you don’t want this skin. What I would give to have your beautiful, young brown skin.”

And then she smiled. And I smiled back. But I still wanted her skin instead of my own.

By the time I was sixteen, and in that store, I was aware of what brown skin meant. I also was aware there was nothing anyone could do about it. Even me. So I gave the woman a twenty-dollar bill and, while Mom stood nearby, the manager said, just loud enough for my ears, “All you people do is come in here and steal me blind.” She slammed the register closed and handed me back my change, and I felt my face burn with shame as I walked through the door. I finally got rid of those jeans before leaving for college two years later. I threw them into a trash bin, unaltered.

And Mom protected us, as a family, making sure no one was aware of how badly our family functioned, with Dad’s alcoholism and abuse and her depression, which became noticeable when we lived in Naselle, Washington. At the time she’d blamed it on the rain; I now blame it on the fact that our family was volatile and fragile. She’d hidden it all so well from the public, from our friends, even from me, that I was unaware of the impact, the designs these dysfunctions etched on our lives.

So when she begins talking into the stereo speakers, there is no rational way to explain it. Therefore, it has to be something beyond my own knowing. Maybe, I think, if you flip a switch, stereo speakers can receive as well as send sounds. I have no idea; I’ve never thought about how electronics work. I just hope no one comes to the door when she is talking into them.

On Thanksgiving Day it is cold. The snow lies a couple of inches thick, covering the driveway, the grass, the outside stairs, while the thinning layer of clouds above indicates that the sun is going to break through at some point. Mom has been up all night talking with the person on the other end of the stereo speaker, and her eyes are wild and tired. As much as I love her, I am increasingly frustrated that she can’t be quiet and just go to bed. The doorbell rings, and I glance at the clock. It’s nine in the morning. We aren’t expecting anyone. Mom follows me to the front door, and I pull it open. Dad stands on the concrete landing, cradling a frozen turkey in his arms. “Happy Thanksgiving,” he says, his smile broad. He extends the bird toward me. A peace offering.

Mom pushes me out of the way. “You goddamned son of a bitch! Get that out of here. You’re trying to kill us!” I look at her face, agitated and filled with anger. Spittle flies from her mouth as she pushes the words out. Her eyes, normally a moderate brown, now shine obsidian, glinting in the frail morning light.

Confusion replaces Dad’s smile. “This is just a turkey,” he explains. “I’m just bringing this for Thanksgiving. I thought you’d appreciate it.”

“Susie, get in here,” Mom hisses between clenched teeth. “It’s a bomb. That goddamned bastard has brought a bomb into this house!” She tries pulling on the sleeve of my T-shirt, but it slips through her fingers as I step out of the house.

“Mom, it’s a Thanksgiving turkey!” I bark. “That’s all.”

Mom looks at me as if I’ve just lost my mind. “That bastard has never done anything without having a plan behind it, and now he wants to blow us up.” She then turns her full attention on the person she had—until recently—been married to for nearly thirty years. “I’m calling the bomb squad.” And with that she closes the wooden door, clicking the lock into place.

Dad and I exchange uneasy glances. Within moments I hear sirens wail their way along Rimrock Avenue. “What the hell has gotten into her?” Dad asks. But I don’t have time to answer; the police have shown up in a white van with an official emblem blazed on its side. The doors slide open, and three men get out, dressed in protective gear. They pull their plastic face guards down and warn Dad to get well away from the bird, but not to leave. They proceed then to take apart the frozen bird, the one he’d purchased at Safeway that morning after pulling into town at the end of a long night of driving. They hack, they cut, they saw at the carcass until it lay in tatters on the hood of Mom’s Oldsmobile. The bomb squad seems to take it all very seriously, while I die the slow death of a seventeen-year-old girl whose mother talks into speakers and whose father is accused of burying a bomb in a frozen turkey that requires the assistance of the Billings Police Department’s bomb squad. I am aware of neighbors who spy, glancing out their doors and windows, blinds and curtains falling quickly into place when I look in their direction. This is the family spectacle of the season, and it is so absurdly public. We have always been such a protectively private family.

“Ma’am, there’s no bomb here,” the head of the squad says, addressing the eye that peeks out of the slit of the barely opened door.

“Yes, ma’am. We’re sure. We’ve taken the whole thing apart, and no bomb has been found.” I can’t tell if he is serious, or if there is the tiniest bit of laughter being held back.

But there is no mistaking the seriousness of Mom’s voice when she screams, “Then you tell that son of a bitch to get off my property!” She slams the door again and immediately turns the deadbolt.

The head of the bomb squad turns around and addresses my dad, his voice tired but measured. “Sir,” he says, his eyes sympathetically averted, “you’re going to have to leave the property.”

“But it’s my property too,” Dad begins to argue, irritation tingeing the words, making them harsh and too loud in the quiet morning.

The sympathy of the officer disappears, and his voice hardens. “Sir, you need to leave the property. I have no idea what this is all about, and frankly, I don’t really care. I’m sure you’re a great guy, bringing a turkey to his family on Thanksgiving, but the lady wants you to leave and we need to ensure you do that.”

“Come on, Dad,” I state and begin to walk toward his truck. The last thing I want is a showdown with the police officer. But then I’m the peacekeeper. I’ve played this role for my entire life.

“Susie, don’t get in that truck,” Mom yells from the house. I look up to see her head against the screen of a window she’s just opened. “He’ll kill you!”

Too many sleepless nights, too much adrenaline, and too much drama causes my temper to snap. I glare at her and yank open the door of Dad’s truck and slide in. Before slamming the door shut, I yell, “He’s okay. I’m okay. Go get some sleep, for Christ’s sake!”

My father slides in on the driver’s side, puts the truck into gear, and backs out of the driveway. We begin a slow crawl down the curved street past the empty house of my best friend, Cari. Thank God she’d moved a few months before and is not privy to what has just transpired. At the end of the street Dad pulls over and asks questions for which I have no answers. I have no explanation for her outburst; I really have no idea what’s just happened. I just know there’s been a break, a rupture, silently rendered, in the fabric of my reality.

“Well, maybe it’s time I move back to Billings, keep an eye on things here,” he says, a spoken thought, as if he’s forgotten I am next to him.

“Don’t move back,” I tell him, quickly and without hesitation. Silence meets my statement, so we sit in the truck while the engine runs, pumping heat into the already stiflingly warm interior. “There’s nothing you can do here. I can take care of it. Your moving back would just make things a whole lot worse.”

Although it sounds like I’m protecting him, I’m not. I am saying I don’t want him in this town. We’ve had a stormy and contentious relationship since I was twelve, and it hasn’t gotten any better. His alcoholism has played a big role, blossoming when I was ten and hitting full bloom by the time I was thirteen. He’d quit drinking a year and a half ago, but it didn’t solve the entire problem. He still had a generally angry nature, which in itself has created an irreparable schism in our relationship. To be honest, having him at a distance has given me a sense of peace, of solace, that I hadn’t felt in years. I don’t want that peace interrupted, especially now when I am under so much pressure trying to deal with my mom.

On the other hand, I do feel a certain amount of empathy for my dad, especially now, seeing him slumped over with his arms on the steering wheel. He seems so much older than when he’d left us a few months ago. It’s clear he was blindsided not only by the divorce but also by the way his wife, now ex-wife, had met him at the front door with curses, epithets, and threats that would make any sailor proud. There is really nothing more to say.

“I guess I’ll get a motel room and grab a couple hours sleep before driving back to Minot.” He wipes his hand along his chin. He looks tired. Tired and beaten. When I get out of the truck, I raise a hand in farewell, but he doesn’t see it. His eyes are on his dismal future. I shove my hands in my jeans pockets and begin the walk toward home, holding my elbows close to my sides as the cold seeps through my thin T-shirt.

When I get back to the house, Mom meets me at the door, and her black eyes scan the street behind me. “Where is he?” she asks warily.

“He left,” I sigh. I enter the front door, tired and dazed. “Since our turkey has been disemboweled by the bomb squad, what are we doing for dinner?”

“Oh,” she says airily, waving away my question with her hand. “We’re having dinner. And we’re having a guest.” She drops her voice. “He’s bringing it.” Anger has been abruptly replaced by a buoyant, careless attitude.

“Who is ‘he’?” There’s a pit in my stomach.

“Oh, you’ll see soon enough,” she hints, then speaks in an excited, low tone. “It’s a surprise.” Her eyes are still jet black, the soft brown of her irises buried beneath the madness. She’s still beautiful, with her long black lashes against pale skin, and her smile at once engaging and whimsical. This look suggests a crush, the beginnings of love; I can’t recall ever seeing this particular look when she was with my dad, ever. I would be happy for her except, given the state of her mind, I don’t think love is a good idea. The pit in my stomach combines with heart palpitations, and her possible romance becomes a feared thing. But it’s happening, regardless of what I want. I begin to set the table for a Thanksgiving Day meal that doesn’t originate in our home.

At some point, when I was in grade school, Dad felt it was important that I be taught etiquette. Hence, the purchase of the book Manners for All Occasions, a book for older children, complete with line-drawn illustrations whose colors were limited to pastel pink and blue. I was enchanted and thumbed through it almost daily, committing its activities and behaviors to memory. I remember being quite impressed with the insistence of the author to act “just so” and telling me just how to do that. Keep in mind, this was just two years after the John F. Kennedy’s assassination, and the United States wasn’t yet finished with the pomp and circumstance of Jacqueline Kennedy. One chapter in particular caught my attention: formal table settings.

I was enamored by the formal setting, memorizing the placement of glasses (both water and wine), cups and saucers, silverware—including the placement of the knife after it had been used—dishes, salad plates, bread plates, bowls, and the ever important cloth napkin that cradled the forks for salad, dinner, and dessert. Our family never entertained like that; my parents were introverts and more interested in growing, hunting, and preparing food than of how to serve it. We were middle class. The book was for someone much more aristocratic than us.

Except on Thanksgiving. That was the day Mom pulled out all the stops and set a very elegant table. And because of Mom’s anticipated guest, I do the same. When I am finished, I stand back and admire my work. The silverware, the Mikasa china set, and the crystal glasses all lie precisely on top of the white linen tablecloth that had been hand-embroidered in delft blue, complete with matching napkins. Standing sentry in the center of the table are a pair of colonial blue candles on their myrtle wood base. I smile. I’ve done it by myself, while Mom is sleeping in her bedroom, and when she wakes up I imagine her reaction of happiness, because I’ll have “done her proud.”

The wall clock reads three. I have no idea when he will arrive, and neither does Mom. But evidently she’s not worried, and I try not to be. But when she comes out of her room an hour later, I ask with the first tinge of worry, “Are you sure he’s going to bring all the food?”

It is the absence that bewilders me. The absence of aroma, the roast turkey, the dressing, the cranberry sauce, the baked rolls, and the clove-spice pumpkin pie. The absence of Dad. The absence of friends. All of it is disconcerting. But the most disturbing absence is my mom, that strong and stalwart person I knew in the springtime has been replaced with someone unrecognizable to me. Her absence has scattered my sense of self to the far corners of the world. My world.

This person who waves away my concern with her hand, an airiness to her voice, her eyes black and unreadable; I no longer know this person. “He’s bringing everything,” she assures me, and there is a sense of weightlessness to her soul, a faith in the universe that I no longer have.

I kneel on the couch and look out the picture window, biting my nails. Will the potatoes be already mashed with gravy on the side? Would he bring canned or fresh cranberries? What about the fruit salad that Mom always serves alongside the meal; did he know how to make it? And would he remember the pumpkin pie? And the whipped cream? I wish we had made the dinner.

Another hour goes by, and Mom is unfazed.

“Are you sure he knows he’s bringing dinner?” I ask again.

“Yes,” she answers easily, unperturbed by my incessant question. “I’m positive. He’s taking care of it all.” Again, that wave of her hand that brushes off concern, a gesture that begins to set me on edge. Usually she is the one worrying and fretting about the details, and I’m unaware of any possible glitches. We have switched roles, and I’m not prepared.

I gather up courage to ask my next question, glancing at her out of the corner of my eye, getting ready to measure her reaction. “So how do you know him?” My words come out slowly, oozing through guarded lips.

“Oh, we work together. His wife left him. Just walked out on him and his two girls.” I give a silent groan. There’s going to be children too? It’s too overwhelming. And Mom’s explanation makes it all sound like gossip. Except she never gossips. A knot forms in my stomach as she adds, “So I invited them.” It seems straightforward enough, but the knot remains.

“What time are they supposed to be here?” Dinner was usually around three, and the clock on the wall said it was five in the afternoon.

“Oh, I don’t know,” she answers with a tinge of disinterest. “I haven’t heard yet.”

The knot tightens. “Is he going to call you to let you know?”

A smile rests on her lips, wily and teasing, as if she’s got a secret. “There are other ways of communicating than through the phone,” she answers with a half smile, raising her eyebrows meaningfully.

Acid coats my stomach. “What way?”

“You have to promise not to tell anyone,” she whispers. Her eyes are wide, like a child’s on Christmas, her lashes so long they touch her dark brows.

“Okay,” I answer, doubt edging my words. “I won’t.”

Her voice drops conspiratorially. “He talks to me through the stereo speakers.” She puts her finger to her lips and nods her head toward the speakers, mouthing the words, Somebody’s listening. She then walks out of the room.

“But I haven’t heard anybody talk to you through the speakers,” I say, following her, my granite world rocking beneath my feet.

“I know,” she says with a wink and a slow nod of her head. “It’s because you don’t know how to listen.”

Mom stops for a moment and looks around, confused, as if she’s suddenly disoriented. She studies the carefully set table, then her gaze wanders to the window, the door, and finally the speakers, where it rests for several moments. Then, quietly, seriously, she excuses herself. “I’m going to lie down for a while.”

“But what if they come?” I know them only as a “they” because I don’t know any of their names! Fingers of anxiety glide along my arms. I don’t want to answer the door without her beside me. There is absolutely nothing familiar about this emotional landscape.

“It will be fine,” she answers, but she sounds tired, the teasing gone. She disappears into her bedroom and shuts the door, and I sit on the couch, silence ringing in my ears. Once, twice, three times the hands of the clock rotate around its face, until it’s almost eight at night. Outside it’s dark, and streetlights dot the landscape. Still there is no sign of the family or of the food. Almost as if feeling my worry, Mom emerges from her bedroom and looks around and then looks at me. I watch in trepidation as her face becomes a mass of confusion, her eyebrows knitting together as if she is trying to solve the most difficult of puzzles. “He’s not here yet?”

I shake my head. She glances at the speaker, the one closest to the dining room table, and cocks her head. She kneels down, placing her mouth near the woofer, and yells, “Where are you?” She pauses and sits back. Nothing. She leans forward once more, her mouth inches away from the fabric. “Aren’t you coming?” Another pause. “You son of a bitch!” Now her voice is shaking with rage. “Answer me!” Mom rises and stares at me, her eyes black wells into the depth of her soul. She stares at me, expressions of hurt and anger vying with each other in a disjointed dance.

“I guess he’s not coming.” She tries to keep her tone light, but a tear courses unimpeded down her lined cheek, and the words are weak and far away. Suddenly, her face crumples along with her composure. “I can’t believe he’s not coming!” She disappears into her bedroom and slams the door. From within I hear her deep, wracking sobs, flooding through the thin veneer that covers the hollow core. I listen to them for an hour. When they stop, I open the door and see Mom curled on the bed, her ribcage rising and falling in the rhythms of sleep. I shut it once I know she’s okay.

My confusion resurfaces as I disassemble the table setting, my motions robotic and repetitive. I return the good dishes to their boxes, the silverware to its flannel blanket, and the glasses to their shelves. I fold the napkins and the linen tablecloth and do anything but think about what just happened. And when the thoughts make their way in, like eels, I wonder if he even knew he was supposed to come on Thanksgiving.