The next day the wild geese intended to travel north through Allbo County in Småland. They sent Yksi and Kaksi there to scout, but when they came back they said that all the water was frozen and the ground all covered with snow. ‘So please let us stay where we are!’ the wild geese said. ‘We can’t travel across a country where there is neither water nor pasture.’

‘If we stay where we are now, we may have to wait a whole lunar cycle,’ Akka then said. ‘It will be better to travel east through Blekinge and see then if we can cross Småland through Möre County, which is near the coast and where spring comes early.’

In this way the boy came to travel over Blekinge the next day. Now, when it was light, he was in his right frame of mind again and could not understand what had got into him the night before. Now he certainly did not want to give up the journey and the wilderness life.

There was a thick fog over Blekinge. The boy could not see what it looked like there. ‘I wonder if it’s good country or poor country that I’m riding over,’ he thought, digging in his memory for what he had learned about the province in school. But at the same time he probably knew that this would be of no use, because he never used to read the lessons.

Suddenly the boy could picture the whole school before him. The children were sitting at the small desks raising their hands, the teacher sat at his desk looking dissatisfied, and he himself was up by the map and supposed to answer a question about Blekinge, but he did not have a word to say. The schoolteacher’s face got darker with every second that passed, and the boy thought that the teacher was more concerned that they should learn their geography than anything else. Now the teacher also came down from his desk, took the pointer from the boy and sent him back to his seat. ‘This will not end well,’ the boy had thought then.

But the schoolteacher had gone up to a window and stood there for some time looking out, and then he whistled awhile. After that he went back to his desk and said that he would tell them something about Blekinge. And what he told them was so amusing that the boy listened. If he just thought about it, he could recall every word.

‘Småland is a tall house with spruce trees on the roof,’ the teacher said, ‘and in front of it there is a wide staircase with three large steps, and that staircase is called Blekinge.

‘This staircase is considerable in size. It reaches eighty kilometres along the front side of the Småland house, and anyone who wants to take the stairs all the way down to the Baltic has forty kilometres to go.

‘A good long time has also gone by since the staircase was built. Both days and years have passed since the first step was cut out of granite and set down level and smooth as a comfortable route between Småland and the Baltic.

‘As the staircase is so old, you can probably understand that it does not look the same now as when it was new. I don’t know how much they cared about such things at that time, but as big as it was, no way could any broom manage to keep it clean. After a few years moss and lichen started to grow on it, dry grass and dry leaves blew down over it in the autumn, and in the spring it was showered with falling stones and gravel. And when all this had to lie there and decompose, at last so much topsoil was collected on the steps that not only herbs and grass, but even bushes and large trees could take root there.

‘But at the same time great differences had developed among the three steps. The top one, which is closest to Småland, is mostly covered with poor soil and small stones, and there no trees will grow other than white birch and bird cherry and spruce, which tolerate the cold at that elevation and are content with little. You can best understand how barren and poor it is there when you see how small and narrow the fields are that have been cleared out of the forest, and how small the cottages are that people build for themselves, and how far it is between churches.

‘On the middle step again there is better soil, and it is not subject to such bitter cold either; there you see at once that the trees are both taller and of finer varieties. Maple and oak and linden, weeping birch and hazel grow there, but no conifers. And you notice even better then that there’s a lot of cultivated ground, and likewise that the people have built big, beautiful houses. There are many churches on the middle step, and large villages around them, and it seems in every way better and grander than the top step.

‘But the very bottom step is still the best. It is covered with good, rich topsoil, and where it bathes in the sea, it does not have the slightest sensation of the Småland cold. Down here beech and chestnut and walnut trees thrive, and they grow so big that they reach above the church roofs. Here are also the largest fields, but the people have not only the forest and agriculture to live on, but they also have fishing and trade and navigation. For that reason the costliest homes are here and the most beautiful churches, and the villages with churches have grown into market towns and cities.

‘But with that not all has been said about the three steps. Because you must bear in mind that when it rains up on the roof of the large Småland house, or when the snow melts up there, the water has to go somewhere, and then of course some of it rushes down the big step. In the beginning it probably flowed down over the whole step, wide as it was, but then cracks arose in it, and gradually the water has been accustomed to flowing down it in some well-developed channels. And water is water, whatever you make of it. It never takes any rest. In one place it digs and files and carries away, and in another it deposits. Those channels it has excavated into valleys, the valley walls it has covered with topsoil, and then bushes and creepers have clung firmly to them so densely and so richly that they almost conceal the stream moving along down in the depths. But when the streams come to the landings between the steps, they have to cast themselves headlong down them, and from this the water comes at such foaming speed it has the power to drive mill wheels and machines, the likes of which have sprung up by every rapids.

‘But even then not all has yet been said about the country with the three steps. Instead it must also be said that up there in Småland in the big house there once lived a giant who had grown old. And it annoyed him that in his advanced age he would be forced to go down the long step to fish for salmon in the sea. It seemed to him much more suitable that the salmon should come up to him where he lived.

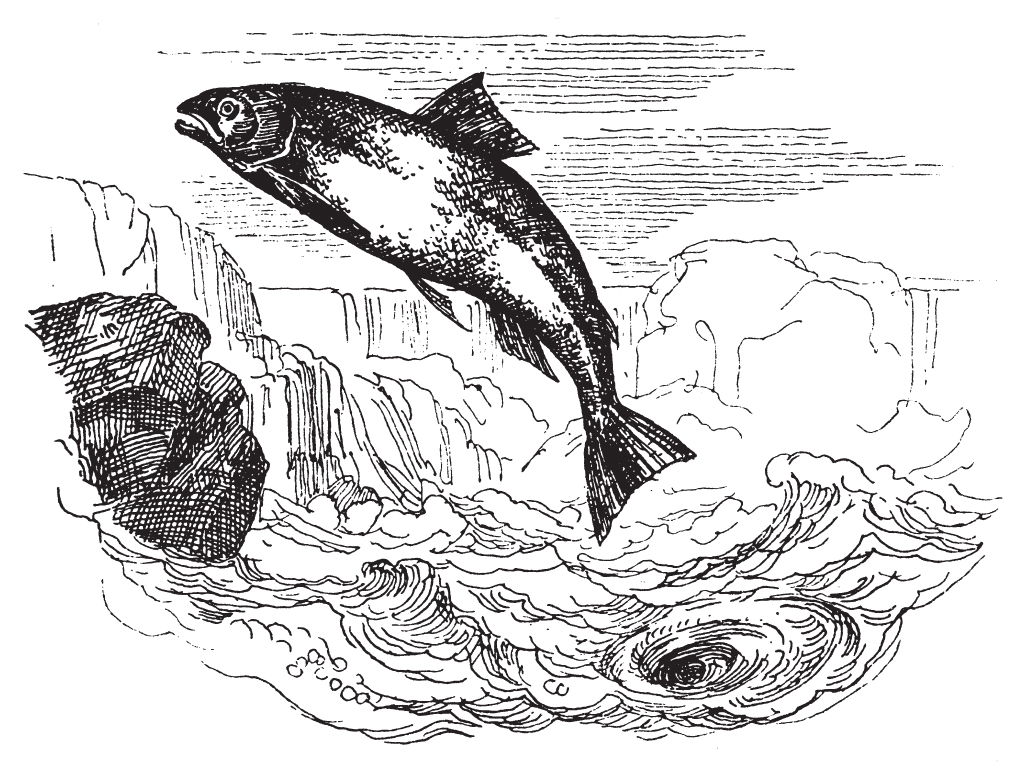

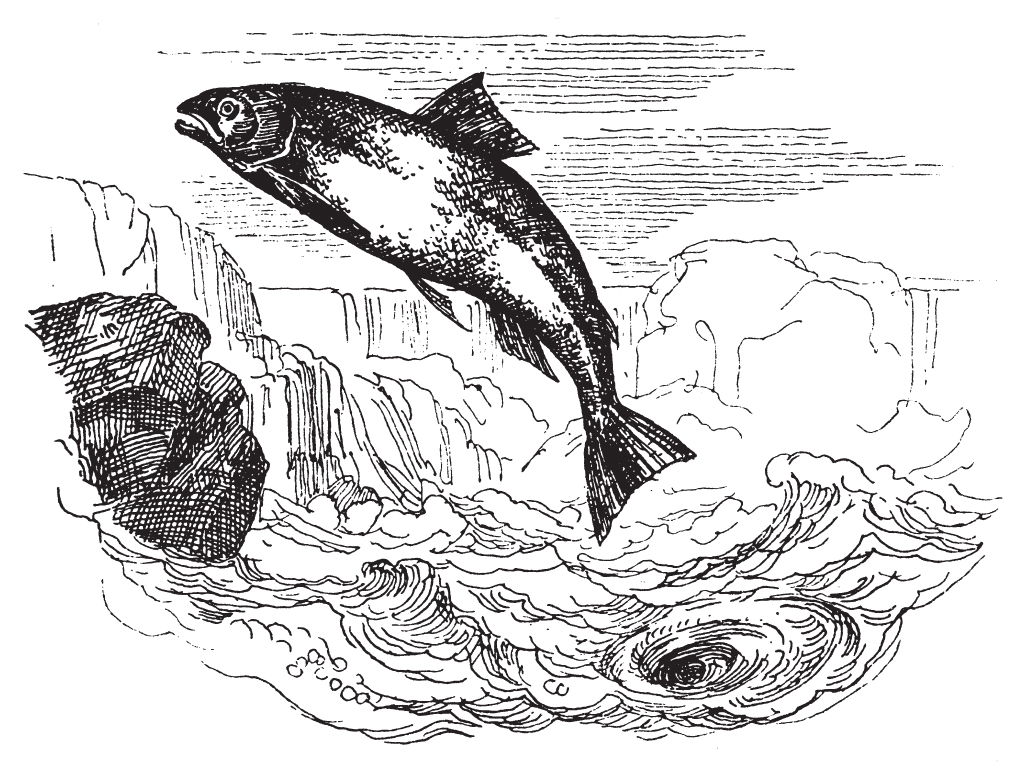

‘For that reason he went up on the roof of his big house, and from there he threw large stones down into the Baltic. He hurled them with such force that they flew over all of Blekinge and fell down in the sea. And when the stones hit, the salmon became so afraid that they came out of the sea, fled up the Blekinge streams, rushed off through the rapids, cast themselves with high leaps up waterfalls and did not stop until they were far inside Småland with the old giant.

‘How true this is, is shown by the many islands and skerries along the coast of Blekinge, which are none other than the many large stones that the giant threw.

‘Along with this you also see that the salmon still enter the Blekinge streams and work their way through rapids and calm water all the way to Småland.

‘But this giant deserves much gratitude and respect from the inhabitants of Blekinge, because the trout fishing in the streams and stonecutting in the archipelago is labour that feeds many of them up to this day.’