The principal’s announcements went through Darwen’s head without engaging his brain. All, that is, but one: the reminder of the sixth grade trip organized by the new world studies teacher, Mr. Octavius Peregrine, whom they welcomed with the obligatory three-second burst of applause. Details of the trip, said the principal, a little uncertainly, had been mailed, though some were still being resolved. Darwen saw Alex grin at that. One of the details as yet unresolved seemed to be where, exactly, the trip would go.

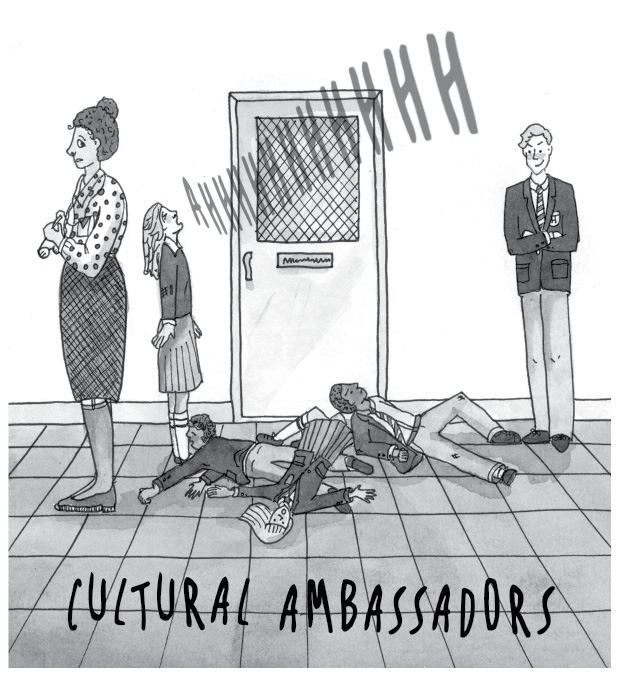

“It’s definitely Costa Rica,” said the principal, looking far from definite, “though the precise . . . er . . . vicinity . . . is still being finalized so that it will coincide with our new world studies teacher’s ongoing research. Hillside’s involvement in such investigation will, I am sure, be another feather in our collective cap. College admission boards are surprisingly impressed by such things. I am also sure that the trip will be an innovative learning experience and that you will serve as our little school’s finest cultural ambassadors. Now let us conclude with the Hillside Academy Principles of Learning.”

As the rest of the students boomed them out (“Memorization, organization, and logic”), Darwen glanced over at Mr. Peregrine, who was smiling and blinking contentedly, unaware of the slightly dubious looks he was getting from some of the other faculty. Darwen wished he was closer. He had to talk to him, tell him what he had learned from Weazen about the name of the tentacled monster. But he couldn’t get to him now, and besides, Mr. Peregrine was talking to an olive-skinned, skinny boy with quick, uneasy eyes whom Darwen had never seen.

“Who’s that?” he asked Rich as they marched out.

“The new kid,” said Rich, eyebrows raised. “Gabriel something. They just introduced him. Weren’t you paying attention?”

Darwen shrugged.

“So,” said Rich. “Do I need to ask where you were when the cops were calling my dad in the middle of the night?”

“No,” said Darwen, lowering his voice. “I was on my way back and my aunt was in my bedroom. I waited behind the oven door, but I fell asleep.”

“You fell asleep?” echoed Alex, who had just joined them, her face like thunder. “How nice, getting a little shut-eye while the rest of the school searched for you. You must have been right chuffed.”

“Don’t you start,” said Darwen.

“That means happy, yeah? Right chuffed?” Alex continued, testing the phrase in her mouth in what was supposed to be a version of Darwen’s accent. “I got an oven door for Christmas. I were right chuffed.”

They entered the homeroom classroom and moved to their desks, Darwen frowning.

“You need to put a lock on your door, man,” said Rich.

“I don’t think my aunt will go for that right now. She thinks I’m . . . I don’t know.”

“Insane?” suggested Alex. “Bonkers? Mental?”

“Sad,” said Darwen. “She thinks I’m not adjusting well to being here, I suppose.”

He looked down, flushing. Rich patted his shoulder awkwardly.

“I’m fine!” Darwen protested. “She’s got it wrong, that’s all. I just couldn’t think up a good enough excuse. I’m fine.”

“Fine,” said Alex with her trademark skepticism. “I’m totally convinced. You hide your feelings about as well as my dog. Hey, Darwen!” she exclaimed with ridiculous enthusiasm. “Wanna treat? Wanna go on the trip? Good boy, Darwen!”

“Funny,” said Darwen.

“You wanna know the truth, Darwen Arkwright?” said Alex, leaning in close. “You wouldn’t have gotten into this mess if you had taken us with you—you know, me and Rich, the people who stood by you every step of the way when the school was about to go down in a blaze of scrobbler glory—instead of going into Silbrica by yourself. So don’t expect sympathy from us.”

Darwen turned to Rich for understanding, but Rich looked down, his face glowing like a stoplight. His friends had clearly had this conversation before without him.

Darwen nodded once, eyes downcast.

“Okay then,” said Alex, as if that closed the matter.

“Stand behind your chairs, class,” said Miss Harvey. “Some of you seem to have forgotten how to conduct yourselves over the vacation. I realize this is your first day back, but I will make no further allowances. Now single file to your first class, which is, I believe—”

“Science, ma’am,” Rich supplied happily.

“Quite so, Mr. Haggerty. Lead the way.”

Rich marched down the hall so quickly that everyone had to jog a little to keep up.

“It’s not a race, Mr. Haggerty!” called Miss Harvey.

“He’s another with Sasha’s gift for self-restraint,” said Alex.

“Sasha?” Miss Harvey repeated.

“My dog,” said Alex. “She’s half husky, half shepherd, and half floppy-eared something else while still only being one dog, not, you know, one and a half. She’s very talented.”

“To class, Miss O’Connor,” said Miss Harvey. “In silence.”

They slowed a fraction, and Darwen felt a foot come down hard on the back of his ankle. He stumbled and fell headlong on the floor, knocking Genevieve Reddock down with him. As Melissa Young shrieked unnecessarily, the class’s neat line broke apart giggling, and several more people managed to fall over in the confusion, including Gabriel, the new boy. Miss Harvey came marching down the corridor shouting about discipline and “all this fooling about.” Darwen rolled over and found himself gazing up into the tanned, handsome face of Nathan Cloten.

“Have a good trip, Arkwright?” he asked, grinning maliciously. Then, as the new boy accidentally bumped him in the ribs, he snapped, “Watch yourself, amigo.”

Gabriel blushed and shuffled away.

Darwen got to his feet and brushed himself off, averting his eyes.

“Darwen, I’m surprised at you!” exclaimed Miss Harvey as she swooped in and started dragging people to their feet.

“It weren’t me, miss,” Darwen sputtered, his Lancashire accent kicking up a gear as it always did when he was flustered. “It were Nathan, right? ’E stood on ma foot and—”

“I am not interested in excuses, Mr. Arkwright,” said Miss Harvey in a chill voice. “Hillside students take responsibility for their mistakes, misjudgments, and misdemeanors.”

Another line from the school brochure, Darwen guessed.

“Now,” said Miss Harvey, “do you think you can make it to science class without treating the other students like pins in a bowling alley?”

“Bowling would be better, miss,” said Alex. “We’d still be standing, and he’d be in the gutter. Trust me. I’ve seen him bowl.”

“That’s enough, Miss O’Connor,” said Miss Harvey. “Off you go. Left, right, left, right.”

And so they did, though the moment they were out of the teacher’s earshot, Darwen could hear Nathan behind him, whining in what he thought was a comical imitation of Darwen’s accent: “It weren’t me, miss. It were Nathan, miss. Miss, will someone teach me to speak English? Please, miss. Only, I’m a complete moron, miss.”

Darwen stared fixedly at the back of Genevieve Reddock’s head. “The sooner I can get on that plane, the better,” he muttered.

“You’re still allowed to go?” said Genevieve, turning, eyebrows raised.

“Of course,” said Darwen, with a rush of panic. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

Genevieve raised her eyebrows, but she said nothing and turned away.

Alex leaned in. “Well, the teachers—not to mention your aunt—think you’ve been climbing out of skyscraper windows,” she said. “They might not all think you’re a juvenile delinquent who breaks windows and sells drugs, but I’m not sure they see you as a cultural ambassador right now.”

Darwen’s heart sank. It wasn’t just a trip. It was a mission. Not going was not—could not—be an option.

The rest of the week was completely dominated by the upcoming trip. Science classes focused on the Central American rainforest, Mr. Peregrine’s world studies classes had turned—albeit hazily—to Costa Rican history and culture, and Spanish classes were swamped with what Nathan derisively called “tourist phrase-book stuff”: “I would like some red beans and rice, please,” “How many pesos does that cost?” and “Why is my luggage in Nigeria?” Everywhere Darwen turned, people seemed to be talking about the trip in excited and panicky terms. Genevieve and Melissa seemed to have been clothes shopping all through the holidays and were keen to break down their travel wardrobes for whomever would listen.

“Of course, we won’t be able to make the final choices,” said Genevieve, “until we know what kind of hotel we’ll be in. If we’re spending most of our time by the pool, that’s going to change the way I accessorize.”

Darwen caught Alex’s eye, and they exchanged a knowing look. If Mr. Peregrine was involved, it was unlikely they would be spending much time lounging by a hotel pool. Of course, if everyone assumed Darwen was a juvenile delinquent, the kind of accommodations Mr. Peregrine had planned would be the least of Darwen’s problems. Conversely, not being there to save the boy would, naturally, rank at the top.

As if she had read his mind, Alex leaned over and whispered, “I have news, by the way. I’ve been reading Costa Rican newspapers online.”

“And?”

“The boy you saw taken was called Luis Vasquez,” she said. “He was the second to go missing.”

Luis, thought Darwen. Finally he had a name.

“And that’s not all,” said Alex. “His brother, Eduardo, kept going into the jungle, searching for him. A week later, whatever took his brother took him too.”

That evening over dinner (pasta with a green, strong-tasting sauce his aunt told him was a “simply divine” pesto), Darwen finally raised the question.

“So, about the sixth-grade trip,” he said, trying to sound casual.

“I got a letter,” said his aunt, palms down on the table, face unreadable.

Darwen knew she had. He had recognized the envelope with its embossed HA emblem and had seen enough to make sure it wasn’t another summons to a parent/teacher meeting about his behavior.

“It’s only a week away,” he said. “I should probably be packing. If I’m going, like.”

He looked at his plate. His aunt wasn’t speaking, but he could feel her eyes on him.

“You want to go,” she said finally.

“Is it too expensive?” he asked, looking up.

“No,” she said, waving the question away. “I can find the money. I may have to work longer hours while you’re gone. . . .”

“So I can go?!” Darwen exclaimed. “I mean, I’m sorry you’ll have to work extra hours. I didn’t know you could work longer hours than you already do. I don’t mean you’re not around enough or anything,” he blundered on, knowing he was making it worse but unable to stop, “I just mean that you work really hard, and I really appreciate it and everything—”

“Darwen,” she said. Darwen stopped speaking abruptly and looked into her shrewd dark eyes. “Where did you go?”

Darwen didn’t need to ask what she meant.

“I never left the apartment,” he said. “I swear I didn’t. I’m fine. I’m happy. I’m not homesick . . . well, not too much. Not usually. And I’m not shoplifting or dealing drugs. . . .”

“Who said you were dealing drugs?” Honoria gasped.

“Just some kids at school,” said Darwen, wishing he hadn’t said it, “trying to get me in trouble.”

“Do you have enemies at school, Darwen?”

Darwen’s brow furrowed. He really wasn’t sure. There were kids like Nathan and Chip who didn’t like him much, but enemies? No. He met her concerned, watchful gaze and shook his head.

“Just, you know, kid stuff,” he said. “Nothing bad. Nothing I can’t handle.”

“And you really want to go on this trip?”

“Yeah! Rich and Alex are going, and there’ll be loads of teachers there too. They’re basically shutting down a bunch of classes for the older kids so enough faculty can go.”

“They do say they have a very high teacher-to-student ratio,” said Honoria approvingly.

“There you go then,” said Darwen. “That’s good, isn’t it? And it’s ‘innovative and experiential learning.’” Honoria nodded sagely, as if she thought this—whatever it was—was a good thing. “And,” Darwen concluded, “Mr. Peregrine is leading the whole thing so . . .”

“So?”

“Well,” Darwen finished lamely, wishing he hadn’t brought the ex-shopkeeper into it at all. “He’s nice, isn’t he?”

“Darwen,” said Honoria very seriously, “he gave you an oven door for Christmas.”

“Right,” said Darwen. “Yes. He’s got a . . . you know . . . quirky sense of humor.”

He tried to smile in an upbeat kind of way. His aunt laid down her knife and fork and sat back, blowing out her breath in a long rush that took her eyes up to the ceiling. At last, she shrugged.

“Okay,” she said. “The books say I’m supposed to let you find yourself so . . . okay.”

“I can go?”

“You can go,” she breathed, swallowing back what Darwen felt sure was a sob. “But keep your nose clean or I’ll cancel, and if I hear so much as a rumor of you wandering off while you’re there, you’ll be on the next flight home, you hear me?”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Darwen, gripping the stone sphere in his pocket.