The following day marked the end of Darwen’s first semester at Hillside Academy in Atlanta, and there was an air of excitement that even the school’s strictness couldn’t quite stifle. One more day and they would be free for two whole weeks of vacation. With a bit of luck, it might even snow.

But Darwen’s mind was elsewhere. One thought burned bright and urgent in his mind as he stared at the stone sphere he had accidentally brought back from Silbrica: he had to find that boy. He had to save him.

Madhulika “Mad” Konkani—a wild-haired girl who once caused a power outage when the kitchens couldn’t produce her vegetarian meal—asked him what he was going to do over the holidays, and he didn’t respond until she flicked him hard on his earlobe. The sixth graders filed into class, where the science teacher, Mr. Iverson, stood owlish at his desk in his oversized glasses and patched lab coat.

“Our last day before the winter vacation,” he said, smiling. “But that doesn’t mean we don’t work.”

A tall blond boy with perfect teeth who was draped in his chair like he owned the entire room and a black boy who was lounging like a bored cat rolled their eyes at each other: Nathan Cloten and Chip Whittley, two of the popular kids who had never taken to Darwen. Nathan yawned.

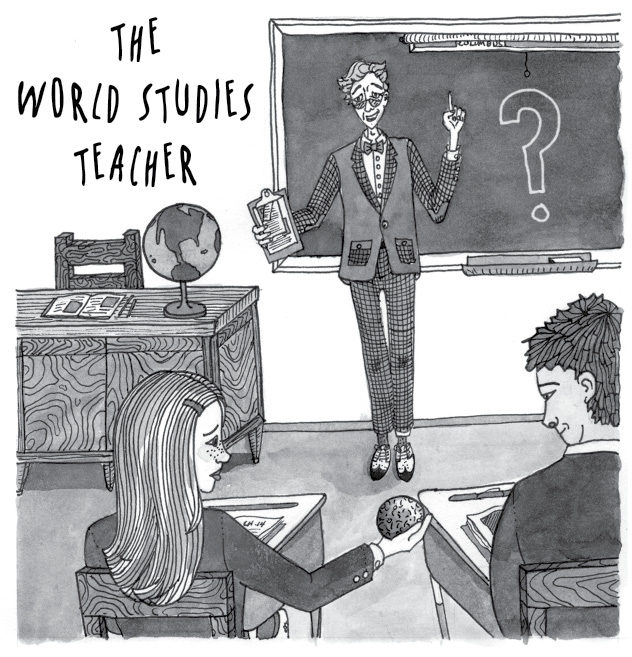

“Today you have a special challenge,” said Mr. Iverson, “at the request of our new world studies teacher. Class, I would like to introduce . . . Mr. Octavius Peregrine.”

“Chuffin’ ’eck!” Darwen exclaimed, using one of his favorite phrases from his native Lancashire, in northern England.

“No way!” Darwen’s friend Alexandra O’Connor exclaimed. “I mean . . . no way! Mr. P. is a teacher? Here?” Her mouth dropped open, her slim black hands clamped together, and her pigtails (jauntily fastened with green glow-in-the-dark plastic skulls that in no way went with her Hillside uniform) bounced as if they might fly off with the astonishment.

“Maybe it’s a different Octavius Peregrine,” said Darwen’s other closest friend, Richard Haggerty, his face as pink as usual. Rich seemed too big for every chair he sat in and looked slightly sweaty and uncomfortable indoors, as if he should be sitting astride a tractor somewhere, chewing on a grass stalk. He had a rich Southern accent and spoke slowly, but everyone knew that he was the smartest kid in the grade, particularly when it came to science.

“Because Octavius Peregrine is such a common name, you mean?” said Alex, deadpan.

Then, as if on cue, the man they had known as a shopkeeper and one of the gatekeepers of the world beyond the mirrors entered the room. Darwen was so dumbfounded that he barely heard a word of Mr. Iverson’s speech about their new teacher’s impressive independent research into the “archaeology and anthropology of ritual spaces and the ancient peoples who used them.” Rich, meanwhile, was gazing at the old shopkeeper with new respect.

Darwen had last seen Mr. Peregrine three days ago, but their history went much further back than that. It was Mr. Peregrine who, while masquerading as a shopkeeper, had given Darwen the portal-mirror that had led him to the magical world of Silbrica. It was because of Mr. Peregrine that Darwen had discovered that he was a Squint, properly called a mirroculist, that rarest of people who can climb through certain darkling mirrors and can even bring along others who are touching them—humans and Silbrican creatures alike.

With his friends Rich and Alex—the Peregrine Pact—Darwen had discovered a threat to the school from a former member of Silbrica’s Guardian Council. The council member, Greyling, had assembled an army of hulking, green-skinned monsters called scrobblers, creatures with huge tusklike teeth and red eyes behind brass goggles, armed with terrible energy weapons. On Halloween those monsters had broken into the human world to take children to fuel their awful power generators. Darwen and his friends had stopped them, but the mirror Mr. Peregrine had given him hadn’t survived the battle. Without that mirror, Darwen couldn’t travel to Silbrica—couldn’t visit its enchanting creatures or see its magnificent machinery. And so Darwen was left stranded in Atlanta, an ordinary but unfamiliar city that Darwen had come to only a few months earlier, after his parents’ death.

But three days ago Mr. Peregrine had produced another mirror. It had been damaged, presumably during the scrobblers’ earlier attack on his shop, and the old man had warned Darwen that this one was “one use only.” Once entered, it would give Darwen a few hours in Silbrica before shutting down forever. This was the mirror Darwen had used last night. And thank goodness he had, or he would not have seen the boy and the monster that had taken him.

And now, amazingly—since he had said nothing of it when Darwen had last seen him—Mr. Peregrine was their world studies teacher!

It was as if the world beyond the mirrors—a world in which Darwen had taken refuge, at least until it had been darkened by Greyling’s war machine—had moved a little closer. Darwen might have no new mirror, but with Mr. Peregrine now a part of his daily life, it was only a matter of time before he could go back to Silbrica and find the missing boy.

Mr. Peregrine was dressed as if he had researched the part of a professor in movies from half a century ago. He wore a tweed suit with leather patches on the elbows, his usual gold-rimmed half-moon spectacles, and a flat-topped mortarboard cap like students wear for graduation. He was carrying a clipboard, and between his lips he held a huge and absurd-looking pipe.

“Er . . .” said Mr. Iverson. “You know you can’t smoke in here, Mr. Peregrine?”

“Really?” said Mr. Peregrine, as if this was most remarkable. “Thank goodness.”

He knocked the contents of the pipe into one of the steel sinks and ran water on the burning tobacco so that for a moment the room was full of aromatic steam.

Baffled and intrigued, the students stared.

“Filthy habit,” said Mr. Peregrine, smiling. “And quite horrible in the mouth. But I do like the smell. Oh,” he said, turning to the class and beaming at them as if only just noticing they were there. “Good morning!”

The class responded in their usual drone (“Good morning, Mr. Peregrine”), but the chorus was ragged and uncertain. Chip and Nathan were leaning forward, their eyes narrow with attention, scouring the new teacher for every bit of information—and any possible weaknesses—they could glean. Darwen realized he was holding his breath, hoping the old shopkeeper would give him a private grin or a wink.

“Have you been discussing my little test?” asked Mr. Peregrine, nodding at Mr. Iverson’s desk.

While everyone had been goggling at Mr. Peregrine, Mr. Iverson had set something beside his notebook: a small stone ball. Darwen’s hand flashed to his pocket where he felt the cool and smooth surface of an identical sphere. He stared at the one on the desk.

What was he playing at? This stuff was secret!

“Your task,” said Mr. Iverson, “is to determine where this object came from. At the end of the allocated time, you will present two possible answers. I want good science here, people. Not guesswork.”

“Immediately after the winter break,” said Mr. Peregrine, “I will be leading you all on a world studies fieldtrip overseas.”

The class muttered excitedly.

“Where to, sir?” asked Rich.

Mr. Peregrine gave a saintly smile. “You tell me, Mr. . . . er . . .”

“Haggerty,” said Rich, playing along. Mr. Peregrine obviously didn’t want the other students suspecting he already knew Darwen and his friends. “But I don’t understand, sir,” Rich pressed. “How should I know where we are going?”

“I mean,” said Mr. Peregrine, “that you will decide where we are going by guessing where this object came from.”

“What if we’re wrong?” asked Jennifer Taylor-Berry in her refined Southern drawl.

“When the class has determined its best guess,” said Mr. Peregrine, “that’s where we’ll go, right or wrong.”

There was a stunned silence. A couple of people laughed, and even Mr. Iverson smiled widely as if he thought this might be a rather odd joke, but as Mr. Peregrine continued to beam serenely, the science teacher’s smile became rather fixed.

“You’re not serious,” Mr. Iverson said at last.

“I am most assuredly,” said Mr. Peregrine. “It seems as good a system for choosing our destination as any.”

“Choosing?” began Mr. Iverson. “But . . . won’t we be—”

“Leaving in three weeks?” Alexandra O’Connor contributed helpfully.

“Precisely so,” said Mr. Peregrine. “So better get a move on.”

And with another broad smile, he turned and made for the door. For a moment, Mr. Iverson seemed rooted to the spot, then he said quickly, “Okay. Get into your groups. I just want to have to have a word with . . . I won’t be long.” And he followed Mr. Peregrine out into the hall.

The silence lasted less than a second before the class burst into a babble of chatter.

“He’s got to be kidding!” exclaimed Naia Petrakis, a girl with jet-black hair and large dark eyes.

“It’s outrageous,” huffed Melissa Young to her best friend, Genevieve Reddock, though she couldn’t help smiling as she said it.

“I think it’s kind of cool,” said Carlos Garcia, and because Carlos so rarely said anything, everyone but Chip and Nathan nodded seriously.

Bobby Park, the Korean boy who Alex thought cut his own hair, gazed at the door through which the teachers had gone and muttered, “Who is that guy?” in an awed voice.

“He is different,” said Princess Clarkson, whose mother was a famous movie star and who was thus assumed to be an authority on style of all kinds. “Classy.”

Darwen and Rich exchanged looks. It was hard to believe, but the students—some of them, at least—thought Mr. Peregrine was cool.

“Oh come on. He’s already booked the trip,” Nathan drawled loudly. “He just wants us to think we have a hand in making the choice. Typical Hillside trying to ‘empower the leaders of the future.’ I, for one, won’t play along. We should say the ball is from Disneyland. Call his bluff.”

He pulled a comic book from his bag and started to read.

Barry Fails had left his seat and pressed his ear to the classroom door. “Shhh,” he hissed. “I think they’re arguing.”

Half of the class immediately thundered to their feet and joined him, straining to hear through the door. Darwen didn’t move. Instead he turned quickly to Rich and Alex and said, “Look.” Holding his hand very close to his stomach so that no one else could see, he took the stone sphere from his pocket and showed it to them.

“He already gave you one?” whispered Rich. “The other kids won’t like it if they think he’s giving you preferential treatment.”

“And they’ll want to know why,” said Alex. “I don’t think we should let on that we already know him.”

“He didn’t give it to me,” Darwen hissed back. “I gave the other one to him! I found them last night—in Silbrica. And that’s not all. I saw a boy. . . .”

He told them everything, and when he had finished, there was a long wide-eyed silence.

“Dang,” said Rich quietly.

“A giant octopus thing with claws,” Alex mused. “Doesn’t Silbrica have any rabbits? Anyway, you shouldn’t have gone in without us,” she scolded. “We made the Peregrine Pact, remember?”

“The boy still would have been taken,” said Darwen. “And if there had been three of us for it to choose from, maybe the creature would have gotten one of us too.”

“You like to live on the edge, I’ll give you that,” said Alex, shrugging off her discontent. “’Course, it’s only a matter of time before you fall over the edge and die horribly. You might want to keep that in mind.”

“I didn’t do it on purpose,” said Darwen.

“Which part?” asked Alex. “Going in without us, activating the weird gate, or going through it? I’d think those things would be pretty hard to do by accident. I mean, what—you hit the button by mistake and then sort of . . . fell through?”

“Of course not,” Darwen retorted.

“Okay,” said Alex. “So when you said you didn’t do it on purpose, what you mean is that you did do it all on purpose, but you didn’t intend to nearly get killed. Uh- huh. Just so we’re clear.”

“The point,” he said, “is that a kid was taken and I want to know what we’re going to do about it.”

“You know,” said Rich, “you might not have been in Silbrica.”

“Of course I was,” said Darwen, “I went in through a mirror, remember? And there was a scrobbler machine of some kind.”

“Yeah, but you went through a second portal, right?” said Rich. “Maybe it didn’t move you to another part of Silbrica. Maybe it moved you to another part of our world.”

“Wait, what?!?” Alex gasped, slamming her hands onto the desk.

Rich shot her an impatient look.

“I suppose,” said Darwen.

“The waterfall place was still light, right?” said Rich. “But the place where you saw the kid being taken was dark, so it must have been somewhere different. It could have been in Silbrica, but it could have been in our world, and in a time zone similar to ours. Western Europe is only five or six hours different, so it might still have been dark there, but the place you describe sounds tropical. Africa or Asia would have been light at that time, so I’d say you were in Central or South America.”

“That’s pretty smart,” said Alex. “He doesn’t look it, but sometimes he’s positively bright.”

Darwen shook his head. “It couldn’t have been our world!”

“Think,” said Rich. “The waterfall area was full of things you could only see in Silbrica. What about the place on the other side of the crystal portal? Was anything there unusual?”

“Other than the massive tentacled monster, you mean?” asked Alex.

“Other than the massive tentacled monster,” Rich agreed.

Darwen sighed.

“I’m not sure,” he said. “It were really dark. There were a lot of plants and trees, but I suppose they looked fairly ordinary. More like houseplants than wild ones, you know? My aunt has one of those umbrella plant things. I’m pretty sure I saw a plant kind of like that.”

“Tropical, then,” said Rich. “And it was hot and humid, right?”

“Yes.”

“What language was the kid shouting in?” asked Alex.

“Not sure,” said Darwen. “But now that you mention it, I think it sounded familiar.”

“Like Spanish?” Alex suggested.

“Could have been,” said Darwen.

“One of the many languages you don’t speak,” mused Alex. “Too bad I wasn’t there to translate. This kid, did he look Latino?” asked Alex. “Like Carlos?”

Darwen shrugged. “I suppose,” he said. “I didn’t really get a good look at him, and as I said—”

“It ‘were’ dark. Yeah, we got that,” Alex concluded.

“And the stone balls?” asked Rich. “You said you threw a few at the monster?”

“Yeah, I found them on the jungle floor. There were at least five of them. Different sizes. I still had two in my hand when I ran for it.”

“And Mr. Peregrine clearly thinks a bunch of random kids can figure out where they came from,” Rich whispered. “There’s no question: you were in our world, Darwen. And if we can find out where the stone spheres originate—”

“We can find out where the boy came from,” Darwen concluded.

“He’s coming back!” yelled Barry Fails. The students scattered like cockroaches caught in a flashlight beam. They fought for their seats, pretending they’d been sitting quietly the whole time, as Mr. Iverson—who wasn’t fooled for a second—returned.

“Well?” he said. “Have you formed your groups?”

There was a grumbling negative murmur throughout the room, but Rich nodded vigorously, indicating Darwen and Alex with his big pale hands.

“First come, first served,” said Mr. Iverson, snatching up the rock and setting it on the desk in front of Rich. “Have a good look, Mr. Haggerty. In five minutes, I’ll be passing it on to the next group. Everyone,” he said, raising his voice, “gets the same access to microscopes and chemicals so you can try to identify what it is. Do not damage the object in the process of your analysis!”

“Where’s Mr. . . . Peregrine, sir?” asked Darwen, trying to sound like he was unsure of the name.

“He went to speak to the principal about his trip,” said Mr. Iverson, his voice carefully neutral. “I expect he may be there awhile.”

Rich lowered his face to the rock. Alex nudged it and it rolled to the edge of the desk, so that Rich had to catch it. Darwen, clutching the other sphere carefully under the desk, scowled.

“It’s a ball,” Alex said. “So someone made it, right?”

“Probably,” said Rich. “But hailstones are round and no one makes them.”

“Really?” said Alex. “I thought hailstones were individually shaped by the great sky god Xanthor and his magic colander.”

“Maybe if it started really high up in a molten state,” said Rich, ignoring her, “like if it was shot from a volcano, it would cool evenly as it fell and come down perfectly round?”

He looked at Darwen as if he might have an answer.

“Don’t look at me,” said Darwen. “You’re the science guy. You want to know about British birds, I’m your man. Otherwise . . .”

“He’s got nothing,” said Alex.

“Which looks about the same as what you’ve got,” said Darwen.

“Yeah?” said Alex, cocking her head. “How about this? It looks like a miniature version of Stone Mountain. Only darker.”

“Stone Mountain?” parroted Darwen.

“Huge granite outcrop just outside the 285 Loop Road,” said Rich absently. “East side of the city. You’re right, Alex. Granite contains quartz, feldspar, microline, and muscovite, and this looks basically the same, but it’s darker.”

Darwen gazed at Rich, impressed. Rich was the president of Hillside’s archaeology club, and he was sixth grade’s most enthusiastic amateur scientist, but he got a lot of his knowledge of Georgia rock from puttering about on his dad’s tiny farm.

“Wait,” Rich said suddenly. “Darker than granite. I know this. It’s granodiorite. It’s like granite but has more plagioclase feldspar than orthoclase feldspar.”

“Great,” said Alex. “I’m really glad it’s got more plagioclase feldspar as opposed to, I don’t know, arcansparklebargle. Anytime you feel like speaking English, you let us know.”

“It’s the same stuff that the Rosetta Stone is made of,” said Rich. “You know, the tablet they used to figure out ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.”

“We’re going to Egypt?” said Alex. “Cool.”

“Not so fast,” said Rich. “Granodiorite is found all over the world, so this could come from anywhere. We’ll need something else to nail down its origin, like maybe a mass spectrometer.”

“Let me check my bag,” said Alex, staring fixedly at him. “Oh dear. I seem to have left all my multimillion-dollar science equipment at home.”

Rich’s scowl deepened over the next five minutes, and when Mr. Iverson swooped in and took the stone ball from him, he exclaimed, “It’s not fair! How are we supposed to figure out where it comes from? If it had unusual plant matter stuck to it, maybe—”

“Sorry, Mr. Haggerty,” said the science teacher. “You’ve had your look.”

Rich sulked as the rest of the class got their turn.

Eventually, Mr. Peregrine returned.

Mr. Iverson was quick to meet him at the door, and Darwen sat up, straining to hear.

“So?” said the science teacher, under his breath.

“So . . . what?” asked Mr. Peregrine, smiling his most serene smile.

“How did your chat with the principal go?” asked Mr. Iverson, glancing over his shoulder at the class so that Darwen had to look down quickly. “About the trip, I mean?”

“Oh!” said Mr. Peregrine, as if this hadn’t been mentioned for weeks. “Oh, that. Yes, he seemed most enthusiastic. Cutting edge, he called it, though I’m not entirely sure what that means.”

“Cutting edge?”

“Yes, my idea of letting my scholarly investigation drive the trip so that the students are, as it were, on the ground doing firsthand research. Seemed most gratified. Charming man, the principal. Charming.”

“Indeed,” said Mr. Iverson, with a slightly fixed smile. “Well, wonderful. That sounds . . . wonderful.” He turned quickly to the class and raised his voice. “Okay, which group wants to make the first argument as to the stone sphere’s origins?”

Darwen shifted, trying to attract Mr. Peregrine’s attention, but the old man ignored him.

“Costa Rica,” said Barry.

Darwen and Rich stared at him. Barry Fails—known, not terribly kindly, as Barry “Usually” Fails—had never answered a question in Mr. Iverson’s class before.

“Specifically,” said Nathan. “A small area close to the border with Panama on the Pacific coast. Possibly a tiny island just offshore called Caño.”

“And your second guess?” said Mr. Iverson.

“We don’t have one,” said Chip with supreme confidence, “and it’s not a guess. It’s from Costa Rica.”

“And how did you reach your conclusion?” asked Mr. Iverson, a skeptical expression on his face.

“Googled ‘stone ball,’” said Barry, brandishing an expensive-looking smart phone and grinning.

Darwen and Alex exchanged outraged looks.

“Can I see that?” said Mr. Peregrine. He was peering at the phone, fascinated. Barry handed it to him, and he turned it over in his hands, gazing at the screen and smiling, rapt.

“What an extraordinary thing!” he whispered.

“It’s just a phone,” said Barry.

“And I think we should talk about scientific process,” inserted Mr. Iverson. “Looking something up on Wikipedia hardly constitutes rigorous analytical—”

“So are they right?” Rich cut in.

“What?” said Mr. Peregrine. “Oh, I see. Well, let me think. Costa Rica . . .” Everyone looked at Mr. Peregrine, who seemed to hesitate before suddenly clapping his hands together. “Is correct!” he exclaimed, apparently writing it down on his clipboard before returning the phone to Barry. “And that’s where we will be going. We’ll begin classes on . . . er . . . ”—he checked the clipboard— “Costa Rica after the holidays.”

Nathan and his friends punched the air in victory, and Barry did a little dance directed at Rich, who was red-faced with fury.

“That’s totally unfair,” he muttered through gritted teeth.

“Look on the bright side,” Alex cut in. “Nobody cares.”

Rich couldn’t argue with that. The students were too thrilled by the idea of visiting a country about which none of them knew anything to worry about how the location had been selected. Darwen couldn’t share Rich’s gloom either. The stone balls had come from Costa Rica, and that meant the boy who had been taken by the monster had been there too. Knowing that meant they were one step closer to saving him. The thought almost made up for Mr. Peregrine behaving as if Darwen was just another nameless student.