THE THING IS, I DON’T UNDERSTAND WHAT KIDS do with themselves any more. I have two boys of my own, I live in a suburb where three out of three fathers are up to here with catching that commuting train and paying that mortgage and burning those leaves and shoveling that snow, and when all else is indefensible, say, “But it’s a wonderful place to raise children.” Spock and Gesell and others of that Ilg are the local deities, the school teachers speak of that little stinker from Croveny Road as “a real challenge,” there are play groups and athletic supervisors and Little Leagues and classes in advanced finger painting and family counselors and child psychologists. Ladies who don’t know a posteriori from tertium quid carry the words “sibling rivalry” in the pocketbooks of their minds as faithfully as their no-smear lipstick.

And yet—I was with a bunch of kids a week ago, ranging in age from ten to fourteen (to forty-one counting me) and since none of them seemed to know what to do for the next fifteen minutes I said to them, “How about a game of mumbly-peg?” And can you believe that not one of these little siblings knew spank the baby from Johnny jump the fence? All right, I thought, they don’t know mumbly-peg, maybe they’re territory players. One of them knew that game. As a matter of fact, he beat me at it, but I figure that was because it was his knife. The wrong kind. When we were kids, we had a scout knife, and for only one reason. Oh, I know it says in the catalogs that the blade is a leather punch, but on my block that narrow fluted blade was a mumbly-peg blade. In an emergency you could punch a hole in something with the blade—but with us it was a knee or a forehead, most often, when we were doing knees or heads in mumblypeg. It was called a scout knife, but it was a mumbly-peg knife.

On my block, when I was a kid, there was a lot of loose talk being carried on above our heads about how a father was supposed to be a pal to his boy. This was just another of those stupid things that grownups said. It was our theory that the grownup was the natural enemy of the child, and if any father had come around being a pal to us we would have figured he was either a little dotty or a spy. What we learned we learned from another kid. I don’t remember being taught how to play mumbly-peg. (I know, I know. In the books they write it “mumblety-peg,” but we said, and it was, “mumbly-peg.”) When you were a little kid, you stood around while a covey of ancients of nine or ten played mumbly-peg, shifting from foot to foot and wiping your nose on your sleeve and hitching up your knickerbockers, saying, “Lemme do it, aw come on, lemme have a turn,” until one of them struck you in a soft spot and you went home to sit under the porch by yourself or found a smaller kid to torture, or loused up your sister’s rope-skipping, or made a collection of small round stones. The small round stones were not for anything, it was just to have a collection of small round stones.

One day you said, “Lemme have a turn, lemme have a turn,” and some soft-hearted older brother, never your own, said, “Go-wan, let the kid have a turn,” and there, by all that was holy, you were playing mumbly-peg.

Well now, I taught those kids to play mumbly-peg, and for all I know, if I hadn’t happened to be around that day, in another fifteen years they would have to start protecting mumbly-peg players like rosy spoonbills or the passenger pigeon—but why don’t the kids teach the other kids to play mumbly-peg? What do these kids do with themselves all the time?

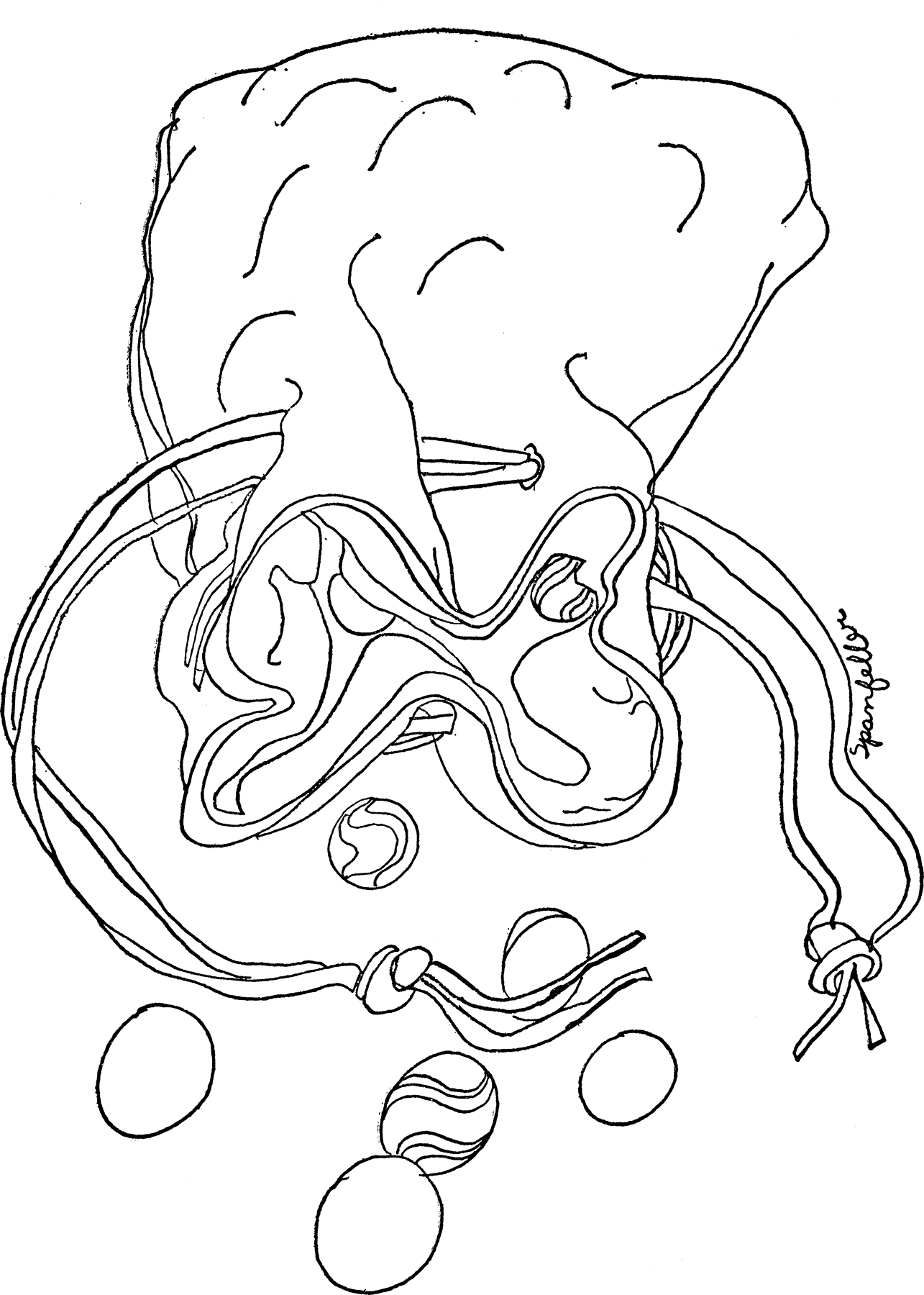

So far as I can find out, they don’t play immies any more. I see in the newsreels every once in a while that they’re holding the national marble championships. What kind of an insanity is this? In the first place, any kid on my block who called an immie a marble would have been barred from civilized intercourse for life. In the second place, who cares who’s marble champion of the world? The problem is, who’s the best immie shooter on the block. And in the third place, they play some idiotic kind of marbles with a ring drawn in paint, and I’ll bet a hat the rules are written down in a book. On my block, the rules were written down in kids. The rules were that as soon as the ground got over being frozen, any right-minded kid on the way home from school, or in recess, planted his left heel in the ground at an angle of forty-five degrees and walked around it with his right foot until there was a hole of a certain size. You couldn’t measure this hole. We all knew what size the hole was supposed to be. I could go outside right now and make a hole the right size. (I did. It’s still the same size. The size of an immie hole. And while I was outside I drew a line with the toe of my foot the proper distance from the hole. It’s still the same distance. It isn’t something you measure in feet. It’s the distance from the immie hole that the line is supposed to be.) Then you stood on the line and, to start, threw immies, underhand, at the hole. There was a kid who moved from another town who said this was “lagging” but we didn’t pay much attention to him. There’s a lot more to immies. There’s fins (or fens) and knucks down and whether it was fair to wiggle your feet while you were doing fins. (Or fens.) There were steelies, which were big ball bearings and could bust an immie and depending on the size of the kids these were legal or illegal, there were realies and glassies. There was the immie bag that your mother made and you put to one side because all right-minded kids carried them in a big bulge in the pocket until the pocket tore. The grownups used to talk about not playing for keeps, which was more nonsense like fathers being pals, and there was the time when I owed a boy I will call Charlie Pagliaro, because that was almost his name, one hundred and forty-four immies. He played me until I had no immies, then he extended me credit, and I doubled and redoubled, and staggered home trying to absorb the fact that I owed him one hundred and forty-four immies. Now the first thing to understand is that there is no such thing as one hundred and forty-four immies. Twenty maybe, or with the help of your good friends, thirty-six, or maybe by going into servitude for the rest of your life to every kid on the whole block, you might get up to about sixty. But there is no such thing as one hundred and forty-four marbles, that’s the first thing. The second thing is that Charlie told me he would cut my head off with his knife—which was no boy scout knife, Charlie being, believe me, no boy scout. The third thing is that I believed Charlie would do it. The fourth thing is that I believed Charlie believed he would do it. I still do. Immies were a penny apiece then.

You go to your mother and say, “I owe Charlie Pagliaro one hundred and forty-four marbles.” Your mother says, “I told you not to play for keeps.” You go to your father and you say, “I owe Charlie Pagliaro one hundred and forty-four marbles.” Your father says, “One hundred and forty-four? Well, tell him you didn’t mean to go that high.”

You go to your best friend. He believes that Charlie Pagliaro will cut your head off. He lends you three immies and a steelie, which, if I remember, was worth five immies, or if big enough, ten, if the guy you were swapping with wanted a steelie at all. Two copies of The Boy Allies and a box of blank cartridges, a seebackroscope you got from the Johnson Smith catalog, and a promise to Charlie Pagliaro that you will do his homework for the rest of your life, twenty-five cents in cash, and that’s it. Charlie takes the stuff, and all you owe him now is fifteen immies. He knows you have a realie. Realies are worth more than diamonds. It is not a good thing to have Charlie mad at you. There goes the realie. You are alive, but poverty-stricken for all time.

(It occurs to me that Charlie Pagliaro may still be alive, and a pillar of the community. It occurs to me maybe you think of him as one of these kids you see around now, with those black leather jackets and motorcycle boots. That’s wrong. I would be lying if I didn’t say that he was tough. I would be lying if I didn’t say that from time to time all of us kids threw rocks at each other, with the avowed intention of killing the other kid dead. I was no pillar of strength, and if it was possible to avoid having a fight with another kid, any other kid, I did. And even then, I had more than my share of fights. We fought and we stole and we lied and defended our honor and we lived by a code that had very little to do with an organization more high-minded than the Mafia. But Charlie didn’t pull a knife on me, I don’t believe he ever pulled a knife on anybody, and all the time we were engaged in juvenile rape and pillage, I never saw a kid deliberately hit another kid with anything but his hands or feet. There were a few wild men, who, aroused into red fury, laid hold of a handy one-by-two and let go, but nobody ever armed themselves for combat. This seems to have changed.)

So, they don’t play mumbly-peg and they don’t play immies. And all you people who are going to tell me about aggies, and the way you played marbles—peace. You played a different way. But whatever way you played, that was the way, that was the only way to play, and you would have had no more of me telling you then than I will of you telling me now. Most of all, did you ever in your whole life conceive of a grownup coming around and having the effrontery to butt into a game? It wasn’t only that he would be silly, he wouldn’t know. Also it was none of his goddam business. Oh, somebody’s big brother, somebody who had used to be around the block, maybe even was going to college—he knew. We used to play football. Nobody ever taught us, we played, and if somebody’s big brother taught you the center was supposed (or not supposed?) to lean on the ball, that you had to get your fingers onto the seam to throw what we called “a sparrow,” that was all right. He was a big kid. He wasn’t a grownup. He was on our side.

I remember a baseball called a nickel rocket. I have a feeling even then inflation was on us and a nickel rocket cost ten cents. The first thing you did with a nickel rocket was to nip into somebody’s garage and hook a roll of friction tape. If the garage was dark enough, for a minute or an hour you would grab the end of the tape and pull it back quickly and see the blue sparks. None of my teachers told me about static electricity, nor did anyone’s father. I don’t even know that they knew about this, or indeed that anybody but me knows about it to this day. Some kid found out that if you pulled the end of the tape back quickly, you saw blue sparks. Some kid told some other kid, and some other kid told some other kid. We knew it. All kids knew it. When we got tired of watching the sparks we wrapped the nickel rocket with friction tape, and if any was left over, we wrapped the handle of the bat with it. I guess I know now the reason we did this with the nickel rocket was that if by any wild chance one of us had gotten a solid hit, the ball would have come apart. But that’s not the point. There was no reasoning going on then. You wrapped a nickel rocket with friction tape because that’s what you did with a nickel rocket. And you put it on the handle of the bat because there was some tape left over. And if there was still some left over, you put it around your wrist, like a strong man. And I have never thought about it until this minute, but why did people keep rolls of friction tape in the garage? We didn’t know. It’s just that that’s where friction tape was. I feel it’s got some connection with automobiles, that it was a way of helping to patch inner tubes, but I wouldn’t bet a nickel either way.

There must have been some time in my life when I played baseball with nine men on a team, but surely it was not on our block. We played with as many kids as were around, and I don’t think there were eighteen kids on the block. We always carefully looked at the bat to make sure the label was up, because if the label wasn’t up, it would split the bat. Is there any truth in this? I don’t know. It was an article of faith, and any kid who didn’t turn the label up was screamed at until he did.

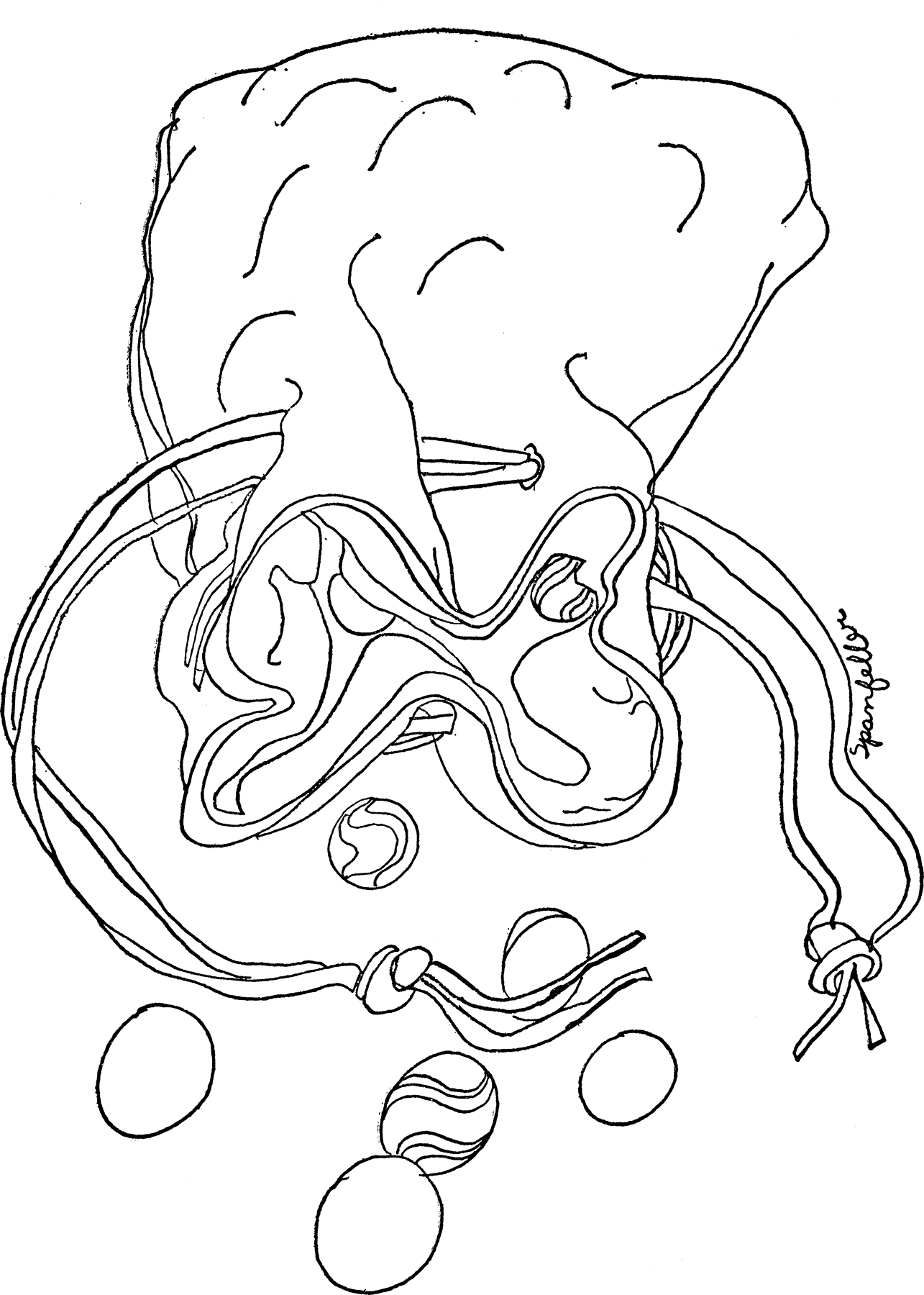

My kids don’t play baseball because of their magnificent inheritance (constitutional sloth and an inability to get out of the way of their own feet), but all the kids I see playing baseball these days are in something called The Little League and have a covey of overseeing grownups hanging around and bothering them and putting catcher’s masks on them and making it so bloody important the kids don’t even know about one o’ cat, or one old cat, or whatever you called it. They tell me these kids in the Little League cry when they lose a game. Nobody ever cried in our baseball games unless he caught a foul tip with the end of his finger, or unless someone slang the bat and caught the catcher across the shins with it, and since it was a kid umpiring, no matter what the score came up finally, you could argue long enough about any decision so that you either won or were robbed. Or some kid had to leave in the middle to practice the piano or go down to the store or go for a ride in his uncle’s new Essex. So, even though we never played nine men on a side, nor were ever in a game that went nine innings, what I remember is the sound of a ball in a glove, and the feeling in my fingers when the bat threatened to split (you vibrated clear up to your ears, and somebody hollered at you to hold the label up) and I remember how somebody got some very precious stuff called neat’s-foot oil (“It comes from the foot of a neat, you dope!”) and we rubbed that in our gloves instead of Three-in-One. And then there was the little kid who had been given a glove that we thought was much too good for him, and from the loftiness of our advanced years, we advised him that the only way to really truly properly break it in was to rub it with horse dung and leave it in the sun.

Kids, as far as I can tell you, don’t do things like that any more. There’s always some interfering grownup around being a pal to them, telling them where to put their feet when they stand at the plate. We found out. Stand the way you wanted to and there was everybody on your side hollering “Take your foot out of the bucket,” and you took your foot out of the bucket. When things got tough for our side, we picked out a real little kid, just big enough to hold the bat and stand at the plate. Just stand there, we told him, and the pitcher would carry on for a while, how it was gypping, who could throw strikes that low, then he’d throw him four straight balls and we had a man—a man!—on base.

Oh, all the wisdom. A kid hit a bunch of fouls. We knew what to say. “He’s gonna have chicken for supper.” Somebody was between you and what you wanted to see. “Sit down,” we’d say, “waddya think, your father’s a glazier?” We had, by the way, no idea of what a glazier was. Two infants would be flailing each other at recess, striking out like windmills and crying bitterly from pure rage. “Hit ’im in the kishkas,” we said, “hit ’im in the bread basket, down in the la bonza, he don’t like it down there.”

We used to play a game called stoop ball. It is my considered reflection that for three months out of every year, for years on end, all we did was play stoop ball. It had to be played with a golf ball, I don’t know why. After a certain amount of time, the golf ball—which we wouldn’t have had at all unless the cover was cut almost to ribbons—would have enough cuts in it so you could pull off the white covering. Then for another three days, what you did was unwind the rubber band. I am not sure what you did with the rubber string you unwound, except to wrap it around various parts of your body until the circulation stopped. Mostly, once again, it was just what kids did. Unwound the rubber. In the center was a little white ball the size of an immie. Inside it, we knew, was something which was so dangerous it was inconceivable. There were two schools of thought. One, that it was an explosive so powerful that, that, that—well jeez, it was an explosive! The other school of thought held that it was a poison that killed, not only on contact anybody who was foolhardy enough to open it, but it would strike dead, on the whole block, every person, cat, collie dog. It could also wither trees and probably melt the pavement.

We cut one open once, and a thick white liquid dribbled out. I was the wise guy. Somebody said it was poison, so I had to say it wasn’t. I touched it. Catch me doing that today! That stuff there, that stuff—why jeez, it’s an explosive!

I suppose this is all just an indication of my advanced years, but I don’t know things now like I used to know then. What we knew as kids, what we learned from other kids, was not tentatively true, or extremely probable, or proven by science or polls or surveys. It was so. I suppose this has to do with ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny. We were savages, we were in that stage of the world’s history when the earth stood still and everything else moved. I wrote on the flyleaf of my schoolbooks, and apparently every other kid in the world did, including James Joyce and Abe Lincoln and I am sure Tito and Fats Waller and Michelangelo, in descending order my name, my street, my town, my county, my state, my country, my continent, my hemisphere, my planet, my solar system. And let nobody dissemble: it started out with me, the universe was the outer circle of a number of concentric rings, and the center point was me, me, me, sixty-two pounds wringing wet with heavy shoes on. I have the notion, and perhaps I am wrong, that kids don’t feel that way any more. Damn Captain Video! And also, I am afraid, damn “The Real True Honest-to-God Book of Elementary Astrophysics in Words of One Syllable for Pre-School Use.”

Once again, it’s because we grownups are always around pumping our kids full of what we laughingly call facts. They don’t want science. They want magic. They don’t want hypotheses, they want immutable truth. They want to be, they should be, in a clearing in the jungle painting themselves blue, dancing around the fire and making it rain by patting snakes and shaking rattles. It is so strange: nobody, so far as I know, sat around worrying about the insides of our heads, and we made ourselves safe. Time enough to find out, as we are finding out now, that nothing is so. Not even close to so.

But then: facts, facts, facts. If you cut yourself in the web of skin between your thumb and forefinger, you die. That’s it. No ifs or buts. Cut. Die. Let’s get on to other things. If you eat sugar lumps, you get worms. If you cut a worm in half, he don’t feel a thing, and you get two worms. Grasshoppers spit tobacco. Step on a crack, break your mother’s back. Walk past a house with a quarantine sign, and don’t hold your breath, and you get sick and die. Play with yourself too much, your brain gets soft. Cigarettes stunt your growth. Some people are double-jointed, and by that we didn’t mean any jazz like very loose tendons or whatever the facts are. This guy had two joints where we had one. A Dodge (if your family happened to own a Dodge) was the best car in the whole world.

We cut our fingers in that web and didn’t die, but our convictions didn’t change. We ate sugar lumps, and I don’t recall getting worms, but the fact was still there. We’d pass by the next day and both halves of the worm would be dead, our mother’s back never broke, my sister had scarlet fever right in my own house and I must have breathed once or twice in all that time, none of our brains got real soft, and we really knew that what came out of the grasshopper was not tobacco juice. But facts were one thing, and beliefs were another.

We got our schoolbooks, and we went home and in a drawer in the kitchen was a pile of wrapping paper saved from packages, and we folded covers for the books in a certain way. Some kids came to our town from New York City, and they told us that you could go to a stationery store in New York and buy covers for schoolbooks, but we got them over lying like that. Some of the girls used wallpaper for their covers, and some of them used glue for the folded-over flaps, but they were wrong. Even they knew that. The right way was to fold it. The drawer with the wrapping paper was the drawer with the string. We were rich. We could have had a ball of string if we wanted one, I guess. But we didn’t, and nobody I knew did. We had pieces of string. To this day I cannot understand why, right now in my own house, we don’t have a drawer with pieces of wrapping paper and pieces of string. My wife, who grew up in New York, buys wrapping paper and throws pieces of string away. She doesn’t save boxes, either, or empty spools, and she doesn’t have a button box. She says that packages largely do not come wrapped in wrapping paper any more, and if they do they are sealed down with tape, and you have to tear the paper to get it off, and I guess she’s right about that, and I suppose there’s nothing really immoral about springing ten cents for a ball of twine, and our kids wear Tee shirts and pants with zippers on them, so where the hell are the buttons going to come from, but that’s all in the realm of reason and you know what kind of sense women make when it comes to reason. She doesn’t even rub the cut-off tip of a cucumber against the rest of it to draw the poison out. She doesn’t even think there’s anything wrong with the kids eating pickles and milk at the same meal. Not that they get sick from it, not that I really think they’re going to—but she isn’t even scared. Why, I tell you about this woman—she thinks it’s all right to go to the movies in the afternoon, and sleep with the windows closed, and once she let the kids have candy before lunch.

My little boy was mooning around the house the other day—it is one of the joys of being a writer that occasionally when I am mooning around the house because I haven’t the vaguest idea of what to do about the second act, or the last chapter, or Life, or why I don’t have an independent income or a liquor store or a real skill like a tool-and-die maker or a lepidopterist or a mellophone player—I can slope downstairs and trap a child. The littler boy was mooning around. I was mooning around. He had no idea what to do with himself because his room is full of wood-burning kits and model ships to be made out of plastic and phonographs and looms and Captain Kangaroo Playtime Kits and giant balloons and plaster of paris and colored pencils and compasses and comic books and money. I will straighten this little bugger out, I said, I will pass on to him the ancient knowledge of his sire, I will teach him a little something about the collective unconscious, by God I will. “Did you ever make a buzz-saw out of a button?” I opened brightly. He thought for a while, and tried to remember what a button was, and concluded that it was something like a zipper, but he didn’t know what a buzz-saw was. He decided that a buzz-saw was like what I almost cut my thumb off with in the cellar and had out of the house by nightfall. “First thing we need is a big button,” I said, and then we went into that thing about, “I don’t know where there’s a button, for the love of God ask your mother, of course there’s a button around the house. Where? In the button box.”

That’s when I found out we don’t have a button box. We went to our neighbor’s and after a while they found a button box. Not their button box, but one that Grandma had had. We got a big button. I strung it with a loop of silk thread, and it didn’t work and the thread broke. I suppose nobody bothers making silk thread strong now, if you want strong thread you use nylon. When I was a kid, silk thread was so strong you practically cut the tip of your finger off breaking it. That was thread. We went to look for string, but all there was was a ball of very good string that was too thick. We went back to the neighbor with the button box and in her kitchen drawer there was an assortment of bits of string. We made a buzz-saw. He took it to day camp with him. The other kids thought it was a new kind of yo-yo and wanted to know where to buy one. When my kid told them his father had made it, they decided he was a liar.

On Sunday I went over to another neighbor. He had called me because he couldn’t stand it around his house any more and wanted to come to my house, but I thought fast and said I’d be over to his house because (I didn’t tell him this) I couldn’t stand my house any more. You know, of course, that visiting in the suburbs is not so much a journey to a friend as a flight from an enemy: home. You sit around a friend’s house and after a couple of hours you are so pleased to discover that your kids don’t spit up their bottles any more—as well they might not at eight and ten—so delighted that your wife doesn’t even try to make you clip the hedge any more, that it’s going to cost him three times as much to put a new roof on as it’s going to cost you to have the porch shored up (neither of you can afford to do either), that his wife has some sort of jackass notion that men are supposed to shave and mix daiquiris for people—well, I tell you, it’s nice to get home.

But this day I thought if I had to watch my wife do one more puzzle in the Sunday paper—she does the crossword, the diagramless crossword, the crossword-less diagram, the cryptogram, the double-crostic, the triple-crostic with a one and a half gainer—if I had to listen to one more of those puny ideas from the littler boy—the older is away at camp and I am spared disquisitions about “Isn’t it interesting that Jupiter has three freeble-tropic moons that travel in an elliptical granster with a mean clyde-bender ratio of . . .”—but the littler boy has problems like, “My counselor said he had a pet mouse and he fed him every day and the mouse got bigger and bigger and one day he exploded, do you believe that’s true, well if it was a joke why wasn’t he smiling when he told me about it?” Another fifteen minutes of this and the inside of my head telling me in louder and louder tones, “You haven’t written a line in two weeks, you’re getting older and you haven’t got a dime in the bank, and if you don’t finish the play—maybe you aren’t a writer at all. After all, you could go to an office and there would be a pile of papers on one side of the desk in the in-basket and at the end of the day you could have moved them all to the other side of the desk to the out-basket and have two weeks’ vacation with pay, and if you can’t write for two weeks, chances are you’ll never write another line as long as you live, and if you do nobody will publish it or produce it or—and drinking isn’t so much fun any more and she’s going to keep on with those goddam puzzles, she doesn’t care, and how the hell do I know. Maybe there is a disease that makes mice explode, and look at that porch, it’s going to fall down any minute.”

Well, you go over to visit a neighbor. Oh, if he could only get away from that desk and those in-baskets and out-baskets, what’s it like to be a free lance, you make a lot of money and you have your time to yourself and you meet glamorous people, and one of his kids is lying belly-down on the dining room table saying, “Moooo . . . moooo . . . oh, mooo.” Papa has some gin and you have some gin, and after a while, another of his kids slopes in and before you know it, you say, “Did you ever make a spool tank?”

He doesn’t know any more about a spool tank than your flesh and blood knew about a buzz saw. You need a spool, a rubber band, a candle and two kitchen matches, you tell him, confident that none of these things will be available. You have a little more gin. He turns up with a rubber band, a candle, and two kitchen matches. He asks his mother for a spool. He comes back with a spool that has at least three feet of thread left on it. You relax, and this mother, this flouter of tradition, goes ahead and tells this kid he can unwind and throw away the three feet of thread. When we were kids, we had to wait at least six months for an empty spool. A spool was empty when the thread was used up. For sewing. There was one big spool in my mother’s sewing box, the kind that they use in factory sewing machines. It would have made a spool tank bigger than any on the block. On the block hell, in the world. It would have used rubber bands cut from an inner tube and a wax washer cut from a plumber’s candle and pencils instead of matches. I wanted that spool more than I have wanted anything else in my life until I was fifteen and saw Mary Astor. I’m still waiting for it. It had thread on it, and when the world was running right, kids who wanted spools had to wait for empty spools.

The thing that bothered me about the spool tank I made the other day (it ran magnificently, as always, and I expect some shrewd fellow is going to bring out a goddam kit for kids to make them, with a plastic spool and a fiberglas washer and a super-latex band), the thing that bothered me is I think I made it at the wrong time. I don’t think it was the spool tank season.

You see, when I was a kid, the year was divided into times. There was a time when you played immies. There was a time when you played stoop ball. There was a time when you built kites. There was a time when you made parachutes out of a handkerchief and some string and a rock. There was a time when you made spool tanks. There was a time when you played football. There was a time when you played Red Rover, and statues, and one and over and Buck Billy Buck and ringeleveo. Everybody did it. It was like the trees coming into green. There was something that clicked, and the gears shifted, and we all got up in the morning and put our immies in our pockets because that was the day everybody started to play immies. And when the immie season was over, we all knew it. We didn’t even talk about it. It was just the end of the immie season, and one morning we stopped playing immies and started making kites, because overnight it had stopped being immie time and started being kite time.

There were other divisions: up until, say seven, boys could play hopscotch. Then, the iron door slammed. From there on out, hopscotch was for girls. On my block, no boy could ever, at whatever age, skip rope. Once in a while, a boy could play higher and higher, which was simply two girls holding the skipping rope (a piece of clothesline, and I’ll get into that later) higher and higher while a boy jumped until he got his foot caught in the rope and fell on his face. Girls could ride boys’ bikes, but boys couldn’t ride girls’ bikes. Girls could play tag, but not leapfrog. (My, we were backward children.) Girls could carry their books in both arms across their bellies, but boys had to carry them in one hand against their sides. Girls could play immies, occasionally, under great conditions of tolerance, but not mumbly-peg—until around fourteen, when boys would let girls do anything, having plans for later that night, under the street lamps.

That’s another thing. Now it is summer, in this perishing suburb where I live, to which we moved because when we lived in the city, we had to go away every summer so the kids could learn about grass. There are the long evenings, and you can hear what the neighbors are saying, and the other night we went out in the back yard to lie on our backs on a blanket and watch the meteor showers, and there is the big problem of the gardeners who overinvested in tomato plants (for years the littler boy could not be talked out of his belief in elves, because mysterious figures appeared in the night and left boxes of tomatoes at the back door) and dogs would be lying in the middle of the road with their tongues lolling out except there is a law saying they must be leashed until five o’clock, so they loll leashed, and cats hide in the weed jungles, and we see baby rabbits caught in the headlight glare, and the neighbor for whose son I built a spool tank came around with a day-lily the size of my head that smells like a sixteen year old girl (not the lady or my head, but the lily). And the town is a tomb. There are no kids, the Pied Piper has been by.

It is summer, and there are the long evenings under the street lamps to talk to girls, to watch the big kids talking to girls, to tease the big kids talking to girls, to be hit by the big kids talking to girls, to play Red Rover, to sit on the porch steps and listen to your father tell Mister Fenyvessey what he thinks of the Republicans, to tell your best friend what your father told Mister Fenyvessey and what Mister Fenyvessey told your father, and what words your father used. It is summer and it is time to get a jelly glass and fill it full of lightning bugs and tie a piece of gauze over the top and take it to your room, and very late at night to see that your finger, where you touched the lightning bug, is glowing too.

But not in our town. The kids are at camp, because, for Heaven’s sake, what are the kids going to do with themselves all summer? Well, it would be nice, I think, if they spent an afternoon kicking a can. It might be a good thing if they dug a hole. No, no, no. Not a foundation, or a well, or a mother symbol. Just a hole. For no reason. Just to dig a hole. After a while, they could fill it with water, if they liked. They might find a stone that they could believe was an axe-head, or a fossil. They might find a penny. Or a very antique nail. Or a bone. A saber-tooth tiger’s kneecap. Or if they didn’t want to fill the hole with water, they could put something in it like a penny, or a nail, or an axe-head, or a dead bird and cover it with dirt and leave it there for a while, so they could dig it up later and see what happens to something that you leave in the dirt for a while. We usually forgot to dig it up, or forgot where we had buried it, but once it was a turtle which had made itself dead, and when we dug it up, some obliging beetles had eaten it clean, and I had an empty turtle shell, and that was a good thing to have.

About the Red Rover. We used to use the names of cars. And if it was a hot evening and you didn’t want to run, you picked out an obscure name like Simplex, and to this day I can hear the calls in the summer evening under the street lamp. “Pierce Arrow, come over. Hupmobile, come over. Locomobile, come over. Stanley Steamer, Kissel, Moon, Essex, come over. Go-wan, there’s no such a car as a Buckboard. Is there, Piggy, is there. It’s a kind of a car, not a make of a car, it’s like saying, Coupe (and that was coo-pay) come over. Mercedes-Benz, come over. Hispano-Suiza, come over. Isotta-Fraschini, come over.” Oh, we were a cosmopolitan crowd.

The kids could have watered the lawn in the summer. I could have watered them when I watered the lawn. When I was a kid, you watered the lawn by standing there and holding the hose and spraying it back and forth. In arcs, and in fountains, and in figure eights, and straight up in the air, energetically, and dreamily and absentmindedly, washing the walk, and the porch and the window screen and your father in the living room reading the paper. You dug trenches with the stream from the hose and filled milk bottles and garbage cans and the back seats of parked cars. And if it was a grownup watering the lawn, you hung around until he said, “Why don’t you kids go ask your mothers if you can get in your bathing suits and I’ll spray you,” and you pounded home and got into the scratchy wool bathing suit and pounded back and there, I tell you, was Heaven on earth, getting wet on a front lawn on purpose.

But now we have sprinklers that are scientific and you can sit indoors watching some people play Red Rover on television while your sprinkler crawls along its hose, spraying a predetermined pattern.

It was a hot day, and the clouds gathered and the rain came, the heavy heavy fat drops of summer making quarters on the sidewalk, and in every house screen doors slammed, and it was, “Mother, mother, can I,” and all over the block kids ran out, in their scratchy woolen bathing suits, dancing up and down in the rain. The kids could have done that in the summer.

They could have found their best friend and gone for a long walk, kicking a can, and after a while, lying on their backs against a hedge somewhere, looking up in the sky and speculating. They could have done the same thing, alone, in the back yard, seeing the shapes swimming in the sky. I forget how old I was when I asked somebody about it, and I was told that those wonderful gliding changing spots were imperfections in the fluid of my eye-ball, that what I was seeing was in my eye. In your eye! For so long, for a child’s years, the sky was full of wonder, these shapes were in the sky, the sky was full of transparent things that swooped and swam. They were almost invisible, and, I thought, almost bodiless, they were there, but you could go right through them, they were animals that lived in the air. You see, we didn’t go around talking about things like this. It’s only now, that I am grown up and know everything, that I talk about this.