Chronologically the last major 1950s female sitcom star to appear on the scene, Donna Reed was also, paradoxically, the one whose show most closely conformed to stereotyped views of the era. Yet Reed herself, whose name would eventually become synonymous with the warm and loving TV mother, was in fact a more complicated person than that image suggests, and quite capable of standing up for herself in order to achieve her goals. Nor was Donna Stone, the lead character of The Donna Reed Show, as one-dimensional as her critics would later imply.

Born Donnabelle Mullenger on January 27, 1921, Reed’s old-fashioned upbringing on a farm in Iowa, where she was the eldest of five siblings, would stand her in good stead to play the matriarch of a loving TV family. Looking back on it, however, she was careful to emphasize that her early life and adolescence during the Depression had been anything but idyllic. “It may have been good training for life,” she later said of her upbringing, “but we had few good times and very little money.”1 As a teenager, Reed moved into town and lived with her grandmother while attending high school. It was in school that she acted for the first time, on the recommendation of a teacher who thought it would help Donna overcome her shyness.

Given her family’s financial status, college might not have been an option for her. However, offered the opportunity to live on the West Coast with an aunt, Reed was able to enroll in Los Angeles City College, entering as a freshman in the fall of 1938. While there, she appeared in a couple of plays, but was not terribly serious about an acting career. Her coursework was designed to prepare her for a secretarial career, which she considered a more realistic goal.

However, in late 1940, while still a college student, Reed entered a beauty pageant, and was named Campus Queen of Los Angeles City College. The victory landed her picture on the front page of the Los Angeles Times. Although she had dabbled in acting at school, she otherwise had little preparation for the expressions of interest from movie studios that resulted from the publication of her photo. But her innocence and beauty were captivating.

MGM casting director Billy Grady later commented, “I remember this beautiful, wide-eyed, frightened child walking into my office. I was struck by her look of—quality. Please underline that 89 times: quality.”2 She was soon given a screen test, in which her co-star was another young hopeful, actor Van Heflin. The test was a success for both Reed and Heflin, and in 1941, she became an MGM contract player for a modest $75 per week. If not a fortune, it was nonetheless quite respectable money for a woman who’d lived in near-poverty as a child.

At MGM, which routinely renamed its actors with monikers more suitable for a marquee, she didn’t remain Miss Mullenger for long. First christened Donna Adams, she soon underwent another change, adopting the stage name she would use for the remainder of her career, though she professed no fondness for it. “I hear ‘Donna Reed’ and I get a picture of a tall, chic, austere blonde, which isn’t me,” she later said. “I’ve never liked that name. It has a cold sound. Donna Reed.”3

Despite her lack of experience, Reed’s work at MGM got off to a quick start. Rather than breaking her in slowly with minor roles, she was quickly cast as one of the key players, along with Robert Sterling and Dan Dailey, in a gangster flick called The Get-Away (1941). From there, she soon went on to appearances in some of the studio’s most popular series, racking up credits in Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), The Courtship of Andy Hardy (1942), and two entries in the “Dr. Gillespie” films that were made after Lew Ayres left the Kildare series.

While working at MGM, she met and befriended a studio makeup artist, William Tuttle, whom she married in 1943. Having kept her burgeoning relationship under wraps, the marriage came as a surprise to many of the actress’ colleagues, as did the divorce that followed in 1945. According to Reed’s biographer Jay Fultz, she became pregnant during her first marriage, but underwent an abortion out of fear that a pregnancy would cost her the career that was then on the upswing.

Reed would remain an MGM contract player through the late 1940s. In 1945, she landed two of her best-remembered roles. She played Gladys Hallward, innocent niece of the artist who painted The Picture of Dorian Gray, and co-starred as a dedicated nurse in John Ford’s war drama They Were Expendable. It was also the year that, having recently divorced Tuttle, she married her agent, Tony Owen, with whom she would later produce The Donna Reed Show. In 1947, they began a family, adopting a son they named Tony, Junior.

Her most iconic movie role, as Jimmy Stewart’s leading lady in the ubiquitous It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), was not then the career triumph that its latter-day following might suggest. In fact, the film received lukewarm critical notices, and was something of a box-office disappointment, failing to live up to the expectations created by the teaming of Stewart and director Frank Capra. Stewart, though liking Reed personally, associated her with the movie’s poor showing. He would later veto re-teaming with her in films like The Stratton Story (1949), preferring June Allyson. (In later years, with the critical reputation of It’s a Wonderful Life quite different, Reed was often invited to testimonial dinners and tributes to Stewart, to which she was known to reply waspishly, “Have you asked Miss Allyson?”4).

Reed’s seven-year contract with MGM expired in 1948. She left the studio with few regrets, bored with the roles she was getting. For the next couple of years, she free-lanced, and concentrated on family life, giving birth to son Timothy in the summer of 1949. Thanks in part to husband Tony Owen’s association with Columbia Pictures, where he served as an assistant to studio head Harry Cohn, she signed a contract there in 1950.

Barely out of her teens, Donna Reed makes her film debut in MGM’s The Get-Away (1941), with Dan Dailey.

Initially, her assignments at Columbia were unmemorable. But it was there that, in 1953, she would land the last of her memorable movie roles, cast against type as Alma Burke, a woman of easy virtue, in the World War II drama From Here to Eternity. In James Jones’ novel, the character was bluntly called a whore, albeit one with “a face like a Madonna,”5 but movie censorship codes of the 1950s did not allow for quite this level of candor.

The movie Alma, formerly a poor but respectable girl from a small town, works at the New Congress Club, “two steps up from the pavement,” which advertises drinks, dancing, and recreation, but whose owner “pays us to be nice to all the boys.” Having been rejected by the man she loved, Alma (known on the job as Lorene) is working at the club only until she can go back home with enough money to support herself and her mother in style, and rejects the idea of marrying Prew (Montgomery Clift), the decent soldier who’s fallen in love with her.

It was a role unlike anything Reed had ever played. She was intrigued by its possibilities, but knew it would be a long shot to beat out more blatantly sexy actresses also in the running. Director Fred Zinnemann, who’d directed Reed a decade earlier in a minor thriller, Eyes in the Night (1942), liked her work but wasn’t enthusi-astic about casting her as Alma. Had Reed not already been on the payroll at Columbia, she probably would have been bypassed for the meaty role. Having won some of his casting preferences, however, Zinnemann acquiesced where Reed was concerned.

Her performance was a revelation, playing the outwardly tough character “so touchingly and so well,”6 as her director later admitted. On March 25, 1954, she was named Best Supporting Actress at the annual Academy Awards. This should have raised her stock considerably at Columbia, but it didn’t. Reed was mystified by the lack of follow-up, and angered by the mediocre Western scripts sent to her in the wake of her Oscar win. She asked for, and obtained, her release from the Columbia contract, but was no happier in her subsequent stint at Universal Pictures, where she undertook legal proceedings when they offered her supporting roles rather than the starring vehicles she’d signed to do.

By the mid–1950s, Reed could see her movie career winding down, and was giving serious attention to television, tempted largely by the financial prospects associated with a hit series. With her husband, Tony Owen, Reed formed a production company, Todon of California, Inc., to assemble a series vehicle for her. Owen was by then a producer in his own right, though none of his projects had really struck fire. Their first project together for Todon was an African adventure film, Beyond Mombasa (1956), which did little to enhance the career of either its leading lady or producer. But what would ultimately emerge from their professional partnership would be The Donna Reed Show, which would be done in collaboration with Screen Gems (ironically, the TV arm of Columbia Pictures, where Reed had been dissatisfied as a contract player).

She was still somewhat leery about a full-time venture into television. By that time, with her movie career slowing down, she had already tried a couple of TV guest-starring roles, and wasn’t terribly impressed. In late 1954, she made her television acting debut on Ford Television Theatre, playing the title role in “Portrait of Lydia” (12/16/54). Of her 2/24/57 appearance on General Electric Theater, cast as an Amerasian woman in an episode called “Flight from Tormendero,” Reed later said, “It’s the worst thing I’ve ever done, but I’m told it got one of the series’ highest ratings. Personally, I think people were fascinated by how bad it was, too hypnotized to turn it off.”7

Surprisingly, given the popularity she would achieve with the relatively simple format of The Donna Reed Show, casting the star as a wife and mother wasn’t the slam-dunk one might assume. In fact, she wasn’t sure the sitcom format was for her, telling one of the series’ early directors, “I’m nervous—I can’t do comedy.”8 But on network television in the late 1950s, there seemed few viable options except sitcoms and Westerns, the latter a genre that rarely placed women in lead roles. After Owen and Reed had considered various roles she might play in a weekly sitcom, it was an executive at Screen Gems, seeing a photo of the star with her real-life family, who suggested the proper setting for The Donna Reed Show.

Family sitcoms were a firmly established subgenre in the 1950s, and Reed would be entering a crowded field with hers. Prior to The Donna Reed Show, most would center on fathers, who were either of the bumbling-but-lovable variety (NBC’s The Life of Riley), or the all-knowing patriarch typified by the enduring Father Knows Best (1954–60). Lead actresses like Best’s Jane Wyatt or Harriet Nelson (The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet) were usually the adjunct to the father figure. Reed’s series would be different, in that it established the primacy of the mother on the domestic front.

Ironically, in taking that stance, The Donna Reed Show would establish a linkage with a later ABC sitcom with which it otherwise had virtually nothing in common—the phenomenally popular Roseanne (1988–97). On the surface, Roseanne, wryly promoted by ABC upon her debut as “June Cleaver, Donna Reed, and Harriet Nelson all rolled into one,” played a mother who would have sent Donna Stone reeling in shock. Still, both shows revolved around a dedicated mother, and shared to some degree a worldview that, according to Roseanne, the men who worked in television had difficulty understanding—“that the female character could drive scenes, that the family functioned because of her, not in spite of her.”9

The pilot of The Donna Reed Show sold to ABC, to debut in the fall of 1958, under the sponsorship of Campbell’s Soup. The stakes were high, and Reed would have no assurance that her TV series would be a hit. The beleaguered ABC, in fact, was firmly in third place with TV viewers, and had never before been home to a hit TV sitcom starring a woman. (The Real McCoys, starring Walter Brennan, and Danny Thomas’ Make Room for Daddy, which jumped to CBS in its fifth season, were among ABC’s few sitcom successes). So many ABC shows, comedic or otherwise, tanked that a comedian’s much-repeated joke in the 1960s was, “Want to end the Vietnam War? Put it on ABC, it’ll be over in thirteen weeks!”

The Donna Reed Show cast its star as Donna Stone, an upper-middle-class housewife and mother living in suburban Hilldale, in an unspecified Midwestern state, where her husband Alex was a successful practicing pediatrician. His busy career would be the explanation for the wife’s primacy in the Stone household. Unlike Ozzie Nelson of ABC’s other family sitcom hit, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952–66), who was so little identified with work that viewers never knew what, if anything, he did for a living, Dr. Alex Stone was a professional whose work life often prevented him from being front and center at home.

Reflecting Reed’s primary status, the actor cast as Dr. Stone, Carl Betz, was a relative newcomer, whose biggest TV credit was a running role in the daytime soap opera Love of Life. While Reed would be billed above the title (“Donna Reed in...”), her TV husband would be credited initially with “featuring Carl Betz.” Rounding out the cast were juvenile actors Shelley Fabares as daughter Mary, and Mickey Mouse Club veteran Paul Petersen as her brother Jeff.

The show’s original opening titles showed Reed, as Donna Stone, seeing her family out of the house in the morning, lunches prepared for the kids, and receiving a goodbye kiss from Dr. Alex. (A later version would show that, having seen her husband and kids safely off, Donna herself had somewhere to be, and hurried out the door behind them).

Although later critics would deride The Donna Reed Show for presenting an extremely stereotypical and outdated picture of American womanhood, its creators thought of it quite differently. Series creator William Roberts, a longtime screenwriter whose credits included The Magnificent Seven (United Artists, 1960), intended the role of Donna Stone to show the many demands placed on stay-at-home moms, who were expected to be “wife, mother, companion, booster, nurse, housekeeper, cook, laundress, gardener, bookkeeper, clubwoman, choir singer, PTA officer, Scout leader, and at the same time effervescent, immaculate, and pretty.”10 Years before it became trendy once again to respect the workload and demands involved in being an at-home mom, Reed played a TV character that depicted the job with respect.

Reed herself saw the series as progressive. “We started breaking rules right and left,” she said of assembling The Donna Reed Show. “We had a female lead, for one thing, a strong, healthy woman. We had a story line told from a woman’s point of view that wasn’t soap opera.”11

Nor did Reed suffer from the typical actress wish to appear younger than she was. Still in her mid-thirties when The Donna Reed Show was being developed, she had no qualms about playing the mother of a teenager, though her own children were younger. Roughly a decade younger than TV moms like Harriet Nelson and Jane Wyatt, she gave motherhood a tinge of glamour it usually lacked on TV.

Donna Reed with her original TV family (left to right): Shelley Fabares (Mary), Carl Betz (Alex), Paul Petersen (Jeff).

In the show’s opener, “Weekend Trip,” the Stones are trying to get away for a mini-vacation, but are impeded by circumstances. Chief among them is Alex’s inability to correctly diagnose the illness of one of his young patients. His medical training notwithstanding, it’s Donna who figures out that the boy isn’t ill at all, just faking because he’s afraid to confront a bully at school.

The Donna Reed Show premiered on September 24, 1958, at 9 p.m., with little fanfare. ABC’s scheduling indicated great faith in the show—or perhaps simply desperation. It would play opposite the long-running anthology series The Millionaire (1955–60) on CBS, and, on NBC, the return to a weekly series of television’s first superstar, Milton Berle, in The Kraft Music Hall. A lead-in from the similarly themed Ozzie and Harriet was hoped to deliver a suitable audience to The Donna Reed Show’s doorstep, but clearly Reed was in for a challenge.

ABC’s promotional ads tied its new show to the long-running Ozzie, billing the hour of family-oriented comedy with the tagline “TWO big happy families.” Of The Donna Reed Show, the network’s copywriters said, “Donna’s married to a handsome baby doctor—and the whole show is one howl after another.”

Initial critical reaction found little to shout about in Reed’s show, though Variety deemed it “a pleasant family situation comedy,” and said it had “a good plus in pert, likeable Miss Reed.”12 Nor, judging from early ratings scores, were viewers immediately drawn in. In October, Berle’s ratings were three times what Reed was pulling in. By all indications, ABC programmers were standing alongside the Wednesday night scheduling board with a wet rag, ready to erase The Donna Reed Show and try again. Resisting network pressure to tinker with the show’s format, Reed and Owen were nervous nonetheless.

Fortunately for Reed, executives at Campbell’s Soup liked the show, if not its ratings, and were willing to give it a little breathing room to see if the audience would find it. If Reed was worried, she didn’t show it. “I’m hopeful,” she told TV Guide that fall. “I think the novelty will wear off for Milton Berle after a month or so and we’ll come out on top.”13

By the latter half of the 1958-59 season, in fact, the tide was turning. Word of mouth may have come into play; whatever the reason, ratings for The Donna Reed Show were climbing. In the spring of 1959, ABC and the sponsor renewed the show for a second season. Berle’s highly touted show would not be so fortunate.

After a shaky start, in fact, The Donna Reed Show would become one of the mainstays of ABC’s schedule, lasting for eight years. In its second season, it would be partially responsible for the sitcom failure of another movie veteran, the competition from Reed’s ratings spelling doom for CBS’ The Betty Hutton Show (1959-60). By then, Reed and Owen had successfully lobbied ABC for an earlier time slot (8 p.m.) that allowed family members of all ages to tune in.

Although Reed’s work in the series would disprove her assertion that she wasn’t funny, she would be presented quite differently from the major female sitcom stars that had preceded her. Largely eschewing slapstick or broad comedy, Reed played a somewhat idealized middle-class mother whose stock in trade was warmth, charm, and a facility for making viewers smile.

In a typical episode, “Tony Martin Visits” (3/2/61), Donna insists she has been wrongly issued a ticket for letting her parking meter expire while she shopped. Insisting on having her day in court, she meets singer Tony Martin, who was cited for speeding on his way through town. Both believe they are innocent, and ask to be given trials—but the date selected for Donna’s hearing will cause the family to postpone a much-anticipated skiing trip. Donna, who insists that the meter malfunctioned—“we have too many machines telling us what to do!” she complains—believes it’s a matter of principle not to pay her $2 fine without having her story heard. She must then decide which is more important—her principles, or the plans with her family.

Though, as the above synopsis suggests, the stories on The Donna Reed Show hardly delved into the more controversial or painful aspects of family life, the depiction of Donna Stone was not really as bland and lifeless as later commentary on the show implied. The show derived gentle humor from her pragmatic approach to child-rearing. In “The Broken Spirit” (1/7/60), when Alex is calling to Jeff upstairs, and annoyed by the lack of response, Donna steps in neatly, saying, “There’s an easier way, dear.” Raising her voice slightly, she calls, “Dinnertime, Jeff!,” which promptly brings him running.

Reed’s light touch even allowed humor a bit stronger, without ever being offensive. In another episode, she cheerfully tells a visitor that she’s not much given to shouting at her children—“a rubber hose is just as effective, and it doesn’t leave marks,” she says, smiling gently as she delivers a line that could almost have come from a Roseanne script.

From the show’s early days, Reed would rack up Emmy nominations for her skillful portrayal of Donna Stone. All in all, she received four Lead Actress nominations, but never emerged victorious. Reed, competing opposite the likes of the much-admired Barbara Stanwyck (for her 1960-61 NBC anthology series), felt critics underestimated the difficulties of playing light comedy, and wasn’t surprised to go home empty-handed.

By the time The Donna Reed Show went into its second season, however, it was firmly established as a hit, and critics were developing an appreciation of its low-key style. A trade paper review of the season opener noted, “Show may actually be classed as bonafide domestic comedy, distinguished from the garden variety situationer in that its characters, although idealized, are not daffy or given to doing silly things for silly reasons. Motivation is generally accounted for here, and the comedy, slight as it is, comes from recognizing h[o]me situations that conceivably may, and often do, occur.”14

Ironically, the woman who would become an icon of American motherhood would feel conflicted about the time that she spent away from her own children while filming The Donna Reed Show. Reed and Owen had four children, two of them adopted. When her ABC series began, the oldest was twelve; the youngest, her daughter Mary Anne, was only a year old.

Spending long hours on the set was sometimes difficult for the star. “Donna misses her children,” said TV spouse Betz. “Some days it’s obvious that she’s depressed, although she’ll deny it.”15 Husband Tony Owen would boost his wife’s spirits with unannounced set visits from their children, as well as flowers delivered with notes counting down how many more episodes she had to go before completing the season’s work.

Though Reed, like Lucille Ball at the time, disavowed strong involvement behind the scenes in the show that bore her name, being careful to credit husband Owen as the producer, she admitted that the fast pace of television work had put new responsibilities on her that she hadn’t had as a movie actress.

“I’ve learned how to make decisions,” she said, “and I mean decisions right now—not tomorrow morning or next week. I don’t mean that I’m running the show—anything but—but Tony consults me, the director will ask me for an opinion, casting wants to know what I think about this or that actor. At MGM all I ever had to worry about was who sent the flowers to the dressing room and did I know my lines for the next scene.”16

Without fanfare, Reed used her ownership of the show to give opportunities to some longtime friends and colleagues. Actor Jimmy Hawkins, who’d played her son in It’s a Wonderful Life, would have a recurring role as Mary Stone’s off-and-on boyfriend. “The Career Woman” (4/28/60) featured a guest appearance by Reed’s fellow MGM alumna Esther Williams. Buster Keaton, another friend from MGM, turned up as well.

Pleased as Reed was that her series was a success, she didn’t anticipate that she would be doing it as long as she ultimately did. “I think three years is ideal for a TV series,” she told a reporter in the late 1950s. “If you can manage to keep going for three years, you’re doing very well. After that, you’re under great pressure to keep up whatever standards you’ve set.”17

The Donna Reed Show was hard work, and at times it appeared that the star’s enthusiasm for her series was waning. In 1962, it took a reduction in the number of episodes filmed per season, and a revamping of the shooting schedule that shortened her work hours, to get Reed to agree to a fifth year of the show.

“Every year since the fourth season Donna has wanted to quit,” said Screen Gems executive William Dozier rather patronizingly in 1964. “But all of us knew it was a game. She wanted to be coaxed. She wanted more money. She’s a woman. We’d settle it, then await the end of the next season when the music would start, and we’d all waltz around again.”18 Reed herself never denied that the financial motive in doing a series was strong, though she cared about the quality of her work nonetheless.

“Well stocked to throw in the towel,” according to the original caption for this Donna Reed Show publicity photo.

As time went on, however, she mastered the complications of balancing work and home. TV’s most nurturing stay-at-home on-screen, Reed herself was in fact re-thinking some of her own assumptions about the role of women in society. Pioneering feminist Betty Friedan, who’d created a controversy with her book The Feminine Mystique in 1963, surveyed television’s images of women in an article for TV Guide, and, without specifically citing The Donna Reed Show, asked, “Why is there no image at all on television of the millions and millions of self-respecting American women who are not only capable of cleaning the sink, without help, but of acting to solve more complex problems in their own lives and in society? That moronic housewife image denies the 24,000,000 women who work today outside the home, in every industry and skilled profession, most of them wives who take care of homes and children too.”19

Friedan might have been taken aback to learn that the actress who played TV’s premier housewife shared some of her misgivings about forcing women into traditional roles. “Maybe the ‘experts’ are crazy wrong when they say an unmarried woman is ‘unfulfilled,’” she told an interviewer in 1964. “Maybe every woman shouldn’t necessarily be married and have children—and a lot of women would be happier and more fulfilled if they didn’t.”20 As for herself, she came to realize after working on The Donna Reed Show for several years that she could be a good mother even though she wasn’t at home all day every day.

If the woman Reed played onscreen was a diplomat, charmingly soft-spoken, and seemingly no challenger of societal norms of the day, interviewers and colleagues were sometimes surprised to find that the actress herself was a bit more complicated. Nor did she hesitate to speak her mind. Explaining why she had largely abandoned film work, aside from a cameo in the Columbia Pictures comedy Pepe (1960), Reed said disdainfully of contemporary movies, “They’re terrible. Directors seem to hate women—make them look as if they’d never seen a comb, and give them roles of unwed mothers and tramps. There’s nothing left for families but Walt Disney and Doris Day.”21

Even by the standards of the early 1960s, however, The Donna Reed Show was often criticized as unrealistic, an idealized portrait of family life that had no real-life counterpart. It was commonly mocked with titles such as The Madonna Reed Show, or Mother Knows Best (in fact, Mother Knows Better, though meant facetiously, was briefly considered as a title for the series). Producer Tony Owen, while not denying that the show accentuated the positive, said he and Reed made this choice consciously. “There’s a good side and a bad side to everyone,” he said. “Sure, they’ll go for the nasty stuff at first, but you have to give them an ideal to look up to.”22

By the 1970s, with the Women’s Liberation Movement in full swing, “Donna Reed” became shorthand for the cliché of the impossibly perfect TV mother, an icon to which no human could possibly compare. Unlike her contemporary Barbara Billingsley, who played another idealized TV mother, June Cleaver of Leave it to Beaver (CBS and ABC, 1957–63), Reed’s own name was usually invoked, rather than that of her character, Donna Stone.

Today, the show is often derided as high camp. In the 2/22/01 episode of Gilmore Girls, the WB series about a thirty-something divorcee and her teenage daughter, Lorelai and Rory (Lauren Graham and Alexis Bledel) are watching Donna Reed Show reruns. Visitor Dean isn’t familiar with the show:

Lorelai: You don’t know who Donna Reed is? The quintessential 50s mom with the perfect 50s family?

Rory: Never without a smile and high heels?

Lorelai: Hair that, if you hit it with a hammer, it would crack?

Dean: So ... it’s a show?

Rory: It’s a lifestyle.

Lorelai: It’s a religion.

The title of this particular episode, incidentally, is “That Damn Donna Reed.”

Like other shows of its kind, The Donna Reed Show profited from viewers’ comfort level in watching a familiar TV family growing up year by year. Taking a leaf from the book of shows like Ozzie and Harriet, Reed and Owen also appealed to younger viewers by spotlighting its teenage cast as singers. Shelley Fabares’ “Johnny Angel,” which briefly hit #1 on the Billboard charts in 1962, was soon followed by “My Dad,” which Paul Petersen sang in a Reed episode of the same name (10/15/62). Both actors recorded for the Colpix label, a division of Columbia.

In 1963, with Reed’s original TV children headed toward adulthood, producer Owen introduced a new member to the Stone household—adopted daughter Trisha, played by Paul Petersen’s young sister Patty. First seen in “A Way of Her Own” (1/31/63), Trisha helped fill the gap when, later that year, Shelley Fabares, ready to pursue other career options, left the show’s regular cast. Mary was sent away to college, though Fabares would return to the show occasionally.

Other cast changes in 1963 included the introduction of Bob Crane (pre–Hogan’s Heroes) and Ann McCrea as the Stones’ neighbors, the Kelseys. Crane, then a Los Angeles disk jockey, made his Donna Reed Show debut, as Dr. Dave Blevins, in the 3/14/63 segment “The Two Doctors Stone.” His guest appearance went over well enough that he was asked back for another episode, “Friends and Neighbors” (4/4/63), in which his character, re-christened Dr. Kelsey, had just married Midge (McCrea) and bought the house next door to the Stones.

Crane and McCrea were signed as full-time regulars that fall, and Midge quickly became Donna Stone’s best friend. The cast additions eventually led to yet another update of the show’s opening titles. In this version, while Donna is, as always, ushering her husband and children out of the house in the morning, neighbors Dave and Midge poke their heads in long enough for the new cast members to be billed as well.

According to series co-star Paul Petersen (Jeff), it was an ABC edict that led to the cast changes—“The network thought we needed neighbors to add a new twist to the show after Shelley left.” Petersen grew fond of Ann McCrea, whose professionalism he admired, but not of Crane, whom he later described as “a really detestable person”23 who brought tension to the working atmosphere at The Donna Reed Show.

The presence of these new characters, however, as well as the advancing age of Donna Stone’s “kids,” did allow for some for more adult-centered stories that were less focused on child rearing. One such episode was “The Tycoons” (10/22/64), which revolves around Alex and Dave’s ups and downs playing the stock market, and the awkwardness that both couples feel when Alex is more successful. (With his winnings, Alex and Donna buy their first color TV set, though The Donna Reed Show itself would remain a black-and-white broadcast for its entire run).

Another, “Peacocks on the Roof” (3/4/65), centers on the family’s concern that Alex, who’s been working long hours, is hallucinating. After falling asleep during a showing of Dave and Midge Kelsey’s vacation slides, Alex sees a peacock in the backyard that eludes everyone else’s view. Dave insists on giving his overworked colleague a physical, but it isn’t until Alex meets a neighbor with a large menagerie of pets that he’s able to prove to Donna that he wasn’t seeing things.

Reed was invigorated by the addition of new characters, telling a journalist, “I think we picked up more viewers because we brought in Bob Crane and Ann McCrea as neighbors. I had been brainwashed to think our audience is mostly kids. Now I’d like to run an even wider gamut with our stories.”24 She became friendly with McCrea off-camera as well. In 1965, when Bob Crane left The Donna Reed Show to star in CBS’ Hogan’s Heroes (1965–71), the most logical explanation for his absence would have been for the Kelseys to move away. But Reed, who enjoyed working with Ann McCrea, insisted that she be retained through the show’s 1965-66 season.

Though she welcomed the opportunity for new stories, Reed had no desire to hog the spotlight. At one time, when she was thinking of quitting her long-running show, she rejected a proposal by husband Owen that would have allowed her to sit out some episodes altogether. While she thought that unfair to the audience, Reed encouraged the writers to develop scripts that gave her co-stars a chance to be front and center. In “Who’s Rockin’ the Partnership?” (1/16/64), for example, Paul Petersen as son Jeff is the pivotal character, the story depicting his summer job running a gas station with friend Smitty. Reed has a secondary role, mostly as observer and commentator on the problems at hand.

Otherwise, the show changed little. Idealized as her character was, Reed gave Donna Stone humanity, as in “When I Was Your Age” (1/22/66), when son Jeff impulsively announces his intention to marry girlfriend Bebe (Candy Moore). Husband Alex tries to be reassuring, but Donna is unnerved nonetheless:

Alex: Now, darling, all teenagers go through this marriage thing.

Donna: Yeah, and a lot of them get married!

Alex: But remember Mary? She made the same announcement when she graduated from high school.

Donna: Well, I was panic-stricken then, and I’m panic-stricken now!

The Donna Reed Show continued to grow in popularity as the seasons passed. During the 1963-64 season, six years into its run, the show was in the Top Twenty in national ratings, clocking in at #16. It became a staple of ABC’s Thursday night schedule, retaining its 8 p.m. time slot, where it was often hammocked by shows of similar appeal like Ozzie and Harriet and My Three Sons (ABC and CBS, 1960–72). In January 1965, ABC added reruns of The Donna Reed Show to its daytime schedule.

Enjoying a long run on ABC, The Donna Reed Show would amass more than 250 episodes before it wore out its welcome. By the fall of 1965, however, ratings were falling, with unexpected competition from CBS’ critically assailed Gilligan’s Island (1964–67). In December, trade papers reported that Reed was on ABC’s chopping block.

Ozzie and Harriet was also fading in popularity, and the network opted to retire both long-running shows in the spring of 1966. In fact, a number of marginally popular black-and-white sitcoms were departing the network schedules—The Patty Duke Show, My Favorite Martian, The Munsters, etc.—often because studios and network executives couldn’t come to terms over the now-mandatory conversion to color broadcasting, and the additional costs associated with it.

Celebrating the end of filming The Donna Reed Show with a wrap party in late 1965, Reed shed a few tears, but had no real regrets about putting her series to rest. “I am happy to have finished that eight-year episode of my life,” she wrote to a friend at the time. “I was eight years at MGM, four years at Columbia, four years at Universal; wonder what the next four or eight years will bring?”25

Professionally, Reed entered a quiet period. She did no guest star appearances on television, had no particular desire to launch a second series, and steered clear of movies as well. “I just wouldn’t do the junk I was offered,” she later explained. “I didn’t like the way films were treating women. Most of the roles were extremely passive—women in jeopardy, poor stupid souls who couldn’t help themselves.”26

For the rest of the 1960s and into the early 1970s, she would add virtually nothing of note to her acting resume, although she would be highly visible in reruns of The Donna Reed Show. The show’s daytime network reruns continued until 1968, after which Screen Gems successfully placed it into syndication. With so many episodes available and legal complications surrounding some of the 1960s segments, the syndication package mostly excluded the sixth and seventh season episodes, though the final season was used.

Like Leave it to Beaver (1957–63) and Gilligan’s Island, The Donna Reed Show would be seen daily on the afternoon rerun schedules of countless local stations. Among those stations, by the 1970s, was Ted Turner’s independent Channel 17 in Atlanta, which he would convert to the enormously successful TBS superstation, with reruns like Reed among the key building blocks.

Her co-stars continued to pursue acting careers post–Donna Reed Show. Carl Betz, after playing second fiddle for so many years, became the star of his own well-received dramatic series, Judd, for the Defense. Betz played a Texas-based criminal attorney in the show, which enjoyed a two-year run on ABC from 1967 to 1969, and netted its star an Emmy Award. Shelley Fabares would continue to be in demand, particularly for sitcom roles, seen as a regular cast member in The Little People/The Brian Keith Show (NBC, 1972–74), The Practice (NBC, 1976-77), and, most notably, Coach (ABC, 1989–97), as leading lady to star Craig T. Nelson.

Petersen, outgrowing his teen idol stage, found acting work less plentiful, and eventually changed careers. Today, he is the founder and director of A Minor Consideration, an advocacy group focused on protecting the interests of child actors. Though he is passionate about the wrongs perpetrated on young performers, he has been quick to clarify that his own experience with Reed and TV father Carl Betz was an exception to the norm.

“They meant the world to me and always will,” Petersen said. “Without their love and rock-solid support, you would not be talking to me. I would be a memory. I’d be one of those Hollywood tragedies.”27

As for Reed herself, when she re-emerged into public view, it was in perhaps the last way her fans might have expected, short of taking a role in the original off–Broadway production of Hair. In 1967, at the urging of former Donna Reed Show scriptwriter Barbara Avedon (later the creator of Cagney & Lacey), Reed became co-chairman of the newly formed Another Mother for Peace, an organization of women opposing U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Attending the 1968 Democratic National Convention and other political rallies, she campaigned for politicians who proposed cutting off funding for the war, and did interviews endorsing AMP’s slogan, “War Is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Things.”

Explaining the genesis of her unexpected activism, Reed said, “I’d been overwhelmed by hopeless despair over the war, having two sons who might have to go to Vietnam to fight in a war I don’t believe in. Then one night at a rally for Eugene McCarthy, a mike was put in front of me unexpectedly, and I heard myself speaking what I thought.”28

In 1971, in a controversy not unlike the ones that would confront a different Republican regime thirty-odd years later, AMP’s discovery of maps showing off-shore oil deposits surrounding Vietnam led Reed to co-author a widely disseminated article in the organization’s newsletter titled, “Are Our Sons Dying for Offshore Oil?” The organization, still active today, would later turn its attention to other issues, including nuclear proliferation, but still maintains its original focus as well, and has protested the U.S.’ involvement in Iraq.

If her antiwar activism wasn’t enough to show that Reed wasn’t the woman she played on TV, her decision in 1970 to file for divorce from Tony Owen clinched the deal. Over the years, many had thought that she was ill-suited to her brash, flashy husband. After 25 years of marriage, with their children mostly grown and out of the house, America’s beloved TV housewife concluded that their differences were too much for them. A year later, she would meet Colonel Grover Asmus, whom, despite their original differences of opinion concerning the Vietnam War, she married on August 30, 1974. He had been proposing to Reed on an almost-daily basis for the past three years.

In the mid–1970s, amidst a nostalgia boom, plans for a Donna Reed Show reunion reached the discussion stage. A similar Father Knows Best special on NBC had pulled high ratings, and there was network interest in a Reed revival. Before it could be done, however, Carl Betz was diagnosed with lung cancer. After his death in 1979, Reed and her co-stars decided not to proceed with the project.

However, after more than a decade of professional inactivity, Donna Reed the actress returned to television in the late 1970s, starring in Ross Hunter’s miniseries adaptation of Helen Van Slyke’s 1976 popular novel The Best Place to Be. Hunter, whose specialty as a producer was glamour (among his biggest successes was the 1959 remake of Imitation of Life, toplining Lana Turner), was more to Reed’s taste than the filmmakers who coaxed older actresses into campy, axe-wielding star turns in horror movies. Reviews were mixed, but Reed was happy with the program, which drew ample ratings for NBC, and represented a rare showcasing of a woman over fifty in a starring role. Given her background with AMP, she was intrigued with the possibility of playing antiwar activist Peg Mullen in ABC’s TV-movie of Friendly Fire (1979), and was disappointed when Carol Burnett snagged that role.

Although leery of the demands that a full-time acting career would bring, she continued to perform periodically during the next few years, making the expected guest appearance on The Love Boat, and playing an uncharacteristically coldhearted role as the headmistress of a posh boarding school in the TV-movie Deadly Lessons (1983). Then, unexpectedly, came the type of high-profile role she thought was behind her, when the producers of CBS’ Dallas (1978–91) invited her to join the regular cast, replacing Barbara Bel Geddes as matriarch Miss Ellie.

After taking a meeting with the show’s producers, Reed happily signed to make her Dallas debut in the fall of 1984. She loved the idea of playing a meaty role in a weekly series again, but without shouldering the responsibility for the entire production as she had done in The Donna Reed Show. If the show itself was a bit more risqué than what she had previously done on TV, the role of Ellie Barnes Ewing itself was dignified and distinctly non-villainous. It would also allow her to draw on her own Iowa roots in playing a woman bred in a rural environment.

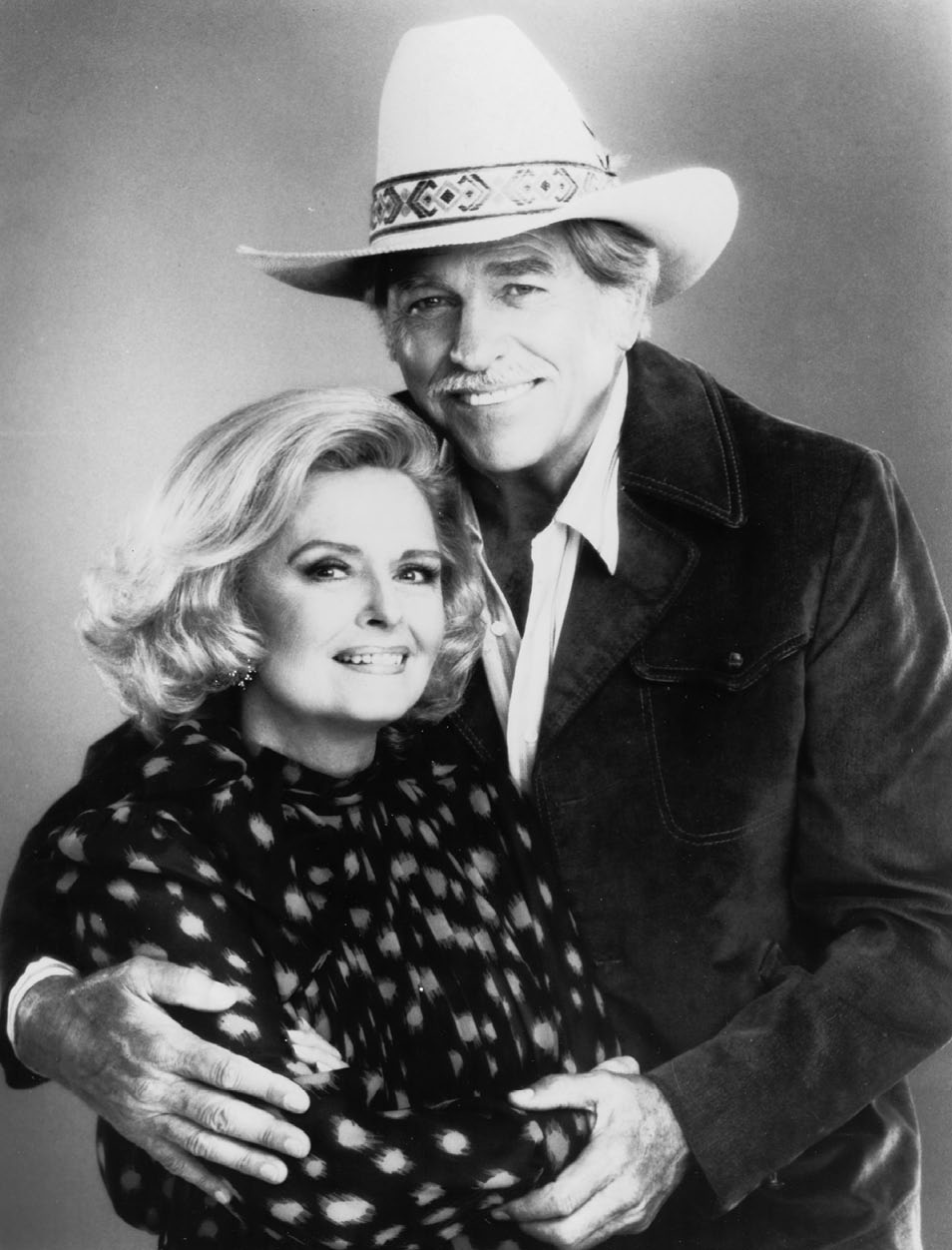

Donna Reed with Howard Keel in a 1984 publicity shot for CBS’ Dallas. Reed’s year playing Miss Ellie proved to be a miserable experience.

Unfortunately, the role that Reed accepted so eagerly turned into the unhappiest episode of her entire career. Rather than trying to mimic her predecessor’s performances, Reed wanted to interpret the character of Ellie as she saw her. However, she soon realized that the producers were fearful of alienating longtime viewers, and didn’t much care for her innovative approach.

“She definitely brought a different take to the character,” said series star Larry Hagman. “I first noticed it in her very first scene. She’d gotten off a plane and was running up the ramp toward Bobby and me. I remember thinking running was something Mama would never do. By this time, viewers knew the character as well as we did, and as much as I adored Donna, she didn’t have the strength or edge that Barbara had given Mama.”29

As the 1984-85 season progressed, other actors’ storylines grew while Reed was relegated to the background. In the spring of 1985, when Bel Geddes, after a year’s rest, felt ready to return to work, Reed was abruptly fired.

Once again, the dispute with the Dallas company would show that Reed was made of sterner stuff than some of the women she played. Offered an “out” by Lorimar, the production company, she refused to go along with their fabrication that she had always intended to have a brief run on the show, and was happy to step aside once her predecessor was well. Instead, Reed bluntly told journalists she had been fired, and that she’d heard it from a reporter before the Dallas producers had had the courtesy to tell her. Angered, the actress asserted her contract had been violated, and promptly filed a lawsuit.

Ultimately, Lorimar would settle the lawsuit by agreeing to pay Reed her $17,250 per episode salary for the remainder of her three-year contract. While the payoff gave her some sense of a wrong righted, the Dallas debacle left her with a sour attitude toward Hollywood. As Hagman later admitted, the episode left Reed “with her trust in the business shattered, and rightfully so.”30 As the actress herself put it in a letter to a friend, “Just remember, nobody ever said show biz was easy, fair, fun, or filled with nice people. Dallas is the pits, obviously.”31

By the time her lawsuit was settled, Reed’s health was failing. In October 1985, entering Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles to be treated for ulcers, she was instead diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Husband Grover Asmus was told that she had about six months to live, but that prognosis proved to be overly optimistic. With few treatment options available, doctors allowed her to go home at Christmastime, and Reed died on January 14, 1986, days short of her 65th birthday.

As it turned out, Dallas would be only a postscript to Reed’s career. Her roles in classic MGM films of the 1940s, and The Donna Reed Show, would be her true legacy as a performer. In 1985, her series would be one of the baby boomer favorites chosen to launch Nickelodeon’s “Nick at Nite” lineup, where it would play until 1994, giving a new generation a chance to discover Reed’s work.

In the wake of Reed’s death, several of her friends and colleagues formed The Donna Reed Foundation for the Performing Arts, based in her home state of Iowa. The organization works to assist Iowa students seeking a performing career, and presents a yearly festival commemorating Reed’s work. Among those organizing the annual event was Reed’s on-screen daughter Shelley Fabares, herself a highly successful television actress who said, “This comes from my absolute enduring love and admiration for Donna.”32 In 2004, the Donna Reed Heritage Museum, located in her hometown of Denison, Iowa, opened its doors to the public.

Given the nature of the role she played, Reed doesn’t always get the credit she deserves as a pioneering sitcom star. Few other women have lasted for eight years on network television in a show that bears their name. Even fewer owned the production company that gave them that exposure.

According to Reed’s co-star Fabares, “Donna gets lumped into a category she doesn’t deserve—the perfect mom, a kind of plastic figure of that long-ago time. She was much, much more. She was a woman of enormous integrity, strength, will, humor, and a capacity to be curious.”33