Daylight shines through the window. The Soldier Boy wakes up naked and bathed in a harsh light that makes his entire body glow. Next to him lies the Innkeeper’s daughter, her body spread out across him, wearing nothing but the bedsheet, which barely covers her. She too is incandescent from the bright light that covers them.

A voice yells out, “Cut!”

An arm reaches out to the man in the bed, holding clothes. George dresses casually. The clothes are not those of a soldier. As he dresses, NICKIE LOUISE WILLY sits up and shouts.

NICKIE: Are we done or are we taking a break? That was really easy. I could do it again. Albert? Are you out there? Was it good? It felt good!

INTERIOR/WAREHOUSE SET—SOUTH OF PARIS/DAY (in color)

The room is exactly the same as what Soldier Boy saw through the hole, but the ceiling is open to the sky. There is no roof. In front of the bed is a thin tripod. On top of it there is a moving picture camera. Standing around the camera are three men. Behind them, the warehouse is empty and seems to expand forever in all directions.

The three men ignore Nickie Willy as they fiddle with the device. Farther behind them is the man Soldier Boy saw through the hole. He sits in a wooden chair watching the men work. Nickie Willy, from the bed, continues to speak.

NICKIE: Albert, did you hear me? I said it was quite easy!

Albert Kirchner, the director, pulls out a pipe and lights it. His bald head and mustache are in full view. This is the same man from the sitting room at the inn.

One of the men walks over and stands next to him, watching the actors dress.

CINEMATOGRAPHER: I thought it would be strange. It’s no different than taking pictures of animals on a farm or a train pulling into a station. It’s really quite easy, isn’t it?

LÉAR (yelling out): Call me Léar, woman, LÉAR!

NICKIE (to George): What did he say?

GEORGE: He wants you to call him Léar. He likes to be called Léar.

NICKIE: Why?

GEORGE: He’s said so a hundred times. Does it matter?

NICKIE: But it’s not really his name.

Léar stands up next to the Cinematographer and they walk back into the emptiness away from the set.

CINEMATOGRAPHER: What are you going to do with this one? One for the arcades? I doubt this could be played anywhere in public, you know. Gaumont just reopened his Palace theater. I don’t expect that they would play this there. So what is the plan? Have you thought about that?

LÉAR: I have thought about it.

CINEMATOGRAPHER: I didn’t think it would really work. I didn’t think you’d find anyone to do it, but you did. How did you do that?

LÉAR: Haven’t you heard? Everyone wants to be in pictures!

CINEMATOGRAPHER: The Lumière brothers will never show this either. Ever.

LÉAR: We can’t sell these pictures to other people to show. We have to show them ourselves. When Edison put the first sound on a cylinder, he didn’t count on anyone else to figure out how to play it back. No! First, one must figure out how to capture it, then how to release it. One step at a time. What we do, my friend, is make pictures. Not just pictures, but pictures of the naked truth. These pictures we collect when sewn together will tell stories the likes of no one has ever seen or experienced before. I’m creating something new here. More than a mere succès de scandale. We are going to bring sexuality to cinema!

CINEMATOGRAPHER: Where did you find them?

LÉAR: Find who?

CINEMATOGRAPHER: Your actors.

LÉAR: Oh, those two? Here and there. A little more there than here. Our investors look bored. You should go and entertain them.

The Cinematographer darts back to the camera that the two men are still admiring.

CINEMATOGRAPHER: Gentlemen, what did you think? We believe that, with your help, we can shoot two of these a week with a triple return of your investment. We just need the equipment for three days a week.

GENTLEMAN 1: Why not just go through Pathé?

GENTLEMAN 2: I’m told he’s built six.

CINEMATOGRAPHER: Well, first of all, the Lumières refused our previous offers of ten thousand francs for a camera alone; Pathé wanted fifteen! And with film stock going for up to fifty francs a meter . . .

LÉAR (suddenly stepping between the two men): Pathé! Pathé wants to own anything that’s shot with his cameras. Edison wants to own it whether it’s shot with his cameras or not. The Lumière brothers won’t show anything they don’t shoot themselves. Nobody wants to share and nobody but LÉAR would be bold enough to put their name behind this. Why would we want to share what is sure to make more money than they could ever imagine making? We are not making their tedious drawing room dramas and light farces. This is the future. This is art.

GENTLEMAN 2: Art. Are you sure? Is that really the idea? I would think this would appeal more to the lower class.

LÉAR: Why shouldn’t the lower class have art? Maybe that’s just what this country needs. An art that will humble the upper class and bring them to their knees. Let’s get everyone on the same level for a change. The lower class is just the upper class without a sitting room. I’m going to get everyone into the same room, I promise you.

GENTLEMAN 1: It doesn’t look very hard. Couldn’t anyone do this?

Léar turns to them and grabs their collars, pulling them toward each other. All three of their faces are inches from each other. Spittle flies as Léar speaks.

LÉAR: It’s easy to shoot pictures of people naked. Anyone can shake their ass in front of a camera. You fellows with your little pricks could even do it. What is difficult, gentlemen, is telling a good story at the same time.

Léar releases them and walks away. The men straighten their coats in shock. The Cinematographer smiles a nervous smile.

CINEMATOGRAPHER: That’s Léar. Don’t take offense. He’s an artist.

The Cinematographer escorts the men to a door at the edge of the warehouse and watches them shuffle out at a loss for words.

INTERIOR/WAREHOUSE SET/SAME

Léar sits on the edge of the bed staring at the camera in front of him. The investors and actors are gone now and the Cinematographer is carefully packing up the delicate machinery.

LÉAR: So they agreed?

CINEMATOGRAPHER: Yes, they did, no thanks to you. If we are going to be asking people for things, you might want to work on your joie de vivre.

LÉAR: When you get back into town, I want you to write to Bernard Natan in Romania. I will arrange passage for him. He will be able to help us.

CINEMATOGRAPHER: Very well. So the film is finished then?

LÉAR: No. The film is not yet finished. What do we have? We have a soldier who comes upon an inn, has his way with an innkeeper’s daughter, and then something happens. Something that changes everything, but what? I shall have to think about the grande finition!

INTERIOR/SOLDIER BOY’S ROOM/SAME

(in black and white)

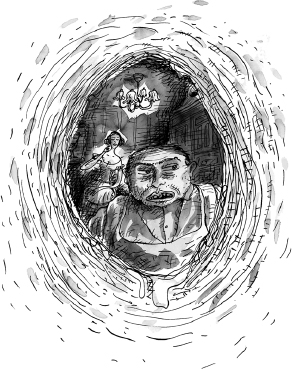

Soldier Boy backs away from the hole and collapses next to it. He is sweating and shaking. There is a hard knock at his door.

SOLDIER BOY: Go away!

INNKEEPER (offscreen): I will not. You haven’t come out of that room in two days! If you’re going to stay any longer, you’ll have to pay! Now! Come on!

Soldier Boy looks back to the hole, which is now double the size it was before.

SOLDIER BOY: Leave me alone. I’m not well.

Soldier Boy can hear whispering on the other side of the door. It sounds like Nicole is whimpering and pleading with her father, who continues to bang on the door. The door begins to shake and rattle as the Innkeeper slams into it with all his weight.

Soldier Boy looks down at the last lines on the paper the Professor gave him.

Without having even finished reading the lines, Soldier Boy has decided. He runs back to the table by the side of his bed and grabs his shirt and his pouch of coins. He punches the hole, making it larger. He steps back to look at the large hole in the wall. A cold, airy, damp darkness within seems to expand without end. The Innkeeper is moments away from busting the door off of its frame. Soldier Boy looks down at the paper one last time, drops it, and then jumps into the hole. He squeezes his midsection through the giant slit; it is just big enough for him to fit through.

The Innkeeper stomps in to find the room now empty and a large hole in the wall. He looks into the nothingness.

INNKEEPER: What can this be? This is impossible. There is a giant hole in my wall! What did he do? Where did he go?

Nicole stands in the doorway, her face swollen from crying.

NICOLE: If I had to guess, Paris.

The Innkeeper notices the paper on the floor and picks it up. The last thing the paper says is: