Over black, heavy breathing of two, a man and a woman. A climax. Silence.

CUT TO:

INTERIOR/INTERROGATION ROOM/DAY

Soldier Boy sits across from Roussou, who, despite decomposition, appears to be in good spirits.

SOLDIER BOY: Roussou? You’re alive!

ROUSSOU: Not very much, I’m sad to say. It’s much harder to keep myself together these days, but otherwise, I’m fit for duty.

His jaw cracks, sways back and forth unhinged on his face, and then falls to the table. Roussou casually picks it up and puts it back on.

SOLDIER BOY: You’re dead?

ROUSSOU: Dead-ish. Yes. [looking down sadly and then shooting back up with a warm smile] But aren’t we all? As for me, it seems I’m no angel. So if I am to stay here longer than I was intended to, I must slowly watch as my skin peels away from my extremities. Only angels have the luxury of vanity. Do you know why that is? Do you know what angels are made of, Soldier Boy?

Before he can answer, something happens.

On the far wall behind Roussou, a small pinhole appears. A light flickers through it. Another appears, and then another. Dozens of tiny holes with tiny flickering lights spray out directly onto Soldier Boy, covering him from head to toe. None of this seems to faze Roussou.

ROUSSOU: You look well. You’re glowing. What have you to report?

SOLDIER BOY: Report?

ROUSSOU: Your mission. Your special mission? Although it is profoundly wonderful to see you, there is business to attend to.

SOLDIER BOY: Well, Roussou, they didn’t give me much direction. None really. I went wandering and I found myself in some pretty tricky situations. I met a girl.

ROUSSOU: Ah, a woman! Was she pretty?

SOLDIER BOY: Which one?

ROUSSOU: My friend, how many have you had?!

SOLDIER BOY: There were two—that is, when I looked through the hole. And so then I entered it.

ROUSSOU: As any man in his right mind would!

SOLDIER BOY: There I was, again, and there she was, again. So I pursued this other woman in hopes of finding this other me.

ROUSSOU: Very good. This is exactly what I would have done. And then?

SOLDIER BOY: It has brought me to Paris. Where we are, aren’t we?

ROUSSOU: You are, my friend. I am nowhere, but once your mission is complete, we can all go home.

SOLDIER BOY: When will that be?

Roussou takes a shining white bottle out of his coat pocket, opens it, and drinks from it.

ROUSSOU: Very soon I hope.

SOLDIER BOY: Roussou, what is that you are drinking? I have seen that bottle before, I think. Maybe I dreamed it?

ROUSSOU: It is what is keeping the dirt and worms at bay, although I must watch my footing when not on solid ground. Those worms are relentless. They call this concoction the Angel Maker, but it doesn’t work very well on those of us who aren’t fit to be angels.

SOLDIER BOY: Do I know what angels are made of?

ROUSSOU: What’s that you say?

SOLDIER BOY: You asked me if I knew what angels are made of. I feel like I should know the answer.

ROUSSOU: Soldier Boy, remember the mission at hand. Paris can be a very intoxicating cocktail, unlike this meddlesome milk. Be sure to drink it slowly. It will try to make you forget what you are looking for and then you will sip it all the more because you realize how parched you truly have been. All we are saying is . . . All I am saying is, don’t forget about me or the rest of us.

SOLDIER BOY: I couldn’t. I wouldn’t.

ROUSSOU: All I am saying, my friend, is, it’s Paris, things might get . . . weird.

The beams of light spread out, covering the entire room and washing everything out except Soldier Boy, who covers his eyes so as to not go blind.

CUT TO:

EXTERIOR/PARIS STREET/NIGHT (in color)

When Soldier Boy removes his arm from his face, he is kneeling down in front of a puddle of water on a paved street. In the water’s reflection, he can see the black sky and thousands of tiny twinkling lights, like shining holes in the sky.

He touches the water and it ripples, distorting the night sky and bending the light. When it settles, he can’t believe what he is seeing.

Flying across the sky is an automobile. He looks up just as it passes overhead. The night sky hides the steel wires that hold it up, attached to a crane that carries it over the buildings and around to the small cargo ship docked along the Seine awaiting it.

It whooshes away out of sight over a dazzling, sparkling sign attached to a building on the corner of the street that reads:

Soldier Boy laughs and smiles like a little child without a care in the world.

Music from nowhere swells and fills the streets, exploding into a deep and grand orchestrated song.

(Music continues through the entire final act.)

SOLDIER BOY (breaking into song): They did it. My God, they really did it! They promised, and they said it, and they did it, they really, really did it! Flying cars and singing stars, they delivered it! If this is a waking sleep, or a living dream, I don’t need to know. If I’m dead don’t revive me. If I’m sleeping don’t ever wake me. If I am sick, then I wanna be sick all the time. If I’m in heaven, then everything is fine. I’ll be here in Paris, among the flying cars and the singing stars. Back in the city that promised they would do it, and they did it, they really, really did it!

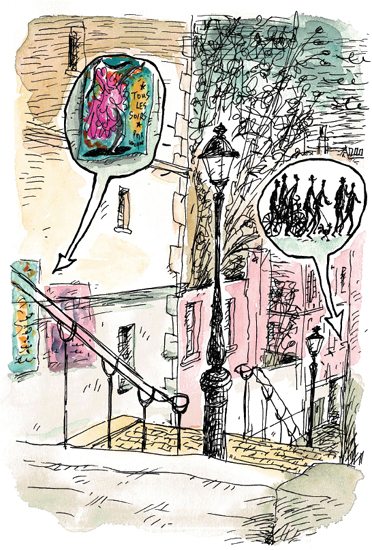

Soldier Boy chases after the flying car, which he sees pass over the giant moon floating above the rooftops of the city, gliding silently through the clouds.

Falling over himself, he tries to run while looking up into the sky following the flying car through the maze of small twisting pathways and alleys between the buildings.

EXTERIOR/COURTYARD/SAME

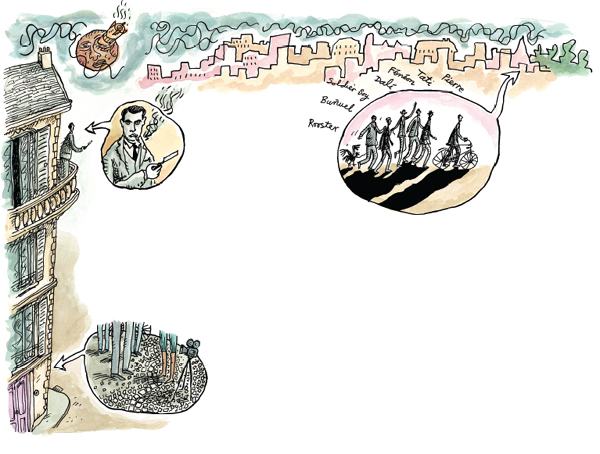

He comes upon a seemingly quiet courtyard. Looking up at the sky, he searches for his flying car, but it is gone and only the giant moon remains. He looks up at a balcony just above the street. A man stands on it staring into the bright silver circle in the sky.

Soldier Boy yells up to him.

SOLDIER BOY: Sir, did you see it? Did you see it? They did it! They really, really did it!

The man is sharpening a shiny blade in his hands. Soldier Boy looks up into the sky to see a cloud slicing through the full moon. It doesn’t seem like the man above can hear him.

A scrawny man pedals by on a bicycle and falls off of it in front of Soldier Boy. He doesn’t get up. Soldier Boy walks over to him and tries to lift him up, but he appears to be dead. Soldier Boy pokes at him.

Soldier Boy turns him over and his eyes pop open. Soldier Boy is startled and falls backward, hitting his head. He is out cold.

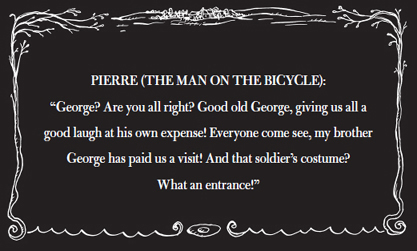

As Soldier Boy comes to, a small crowd has congregated around him. Standing in front is the man with the bicycle. He is talking, but Soldier Boy cannot hear a word he says.

Another man comes up from behind the man on the bicycle. This is the man from the balcony. He holds the same sharp and shiny blade in his strong hand menacingly as a cigarette dangles from his mouth.

As Pierre speaks, not a word comes out of his mouth. Buñuel leans down over Soldier Boy and says . . .

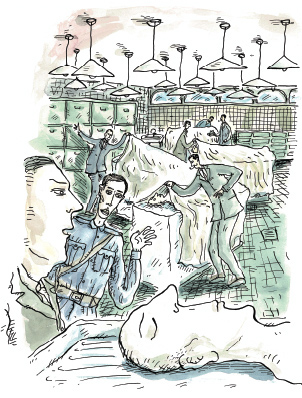

Soldier Boy is helped up by his seemingly old friends, who all pat him on the back and poke at his silly costume. This is the crew of the film shoot that he has wandered into. All around he can hear every sound the city has to offer save for the sound coming out of the mouths of his company.

SOLDIER BOY: I can hear myself, but I cannot hear a word you say when you open your mouths. I SEE your words, but I do not hear them!

The film crew surrounding Soldier Boy begins to break down the night’s equipment while Pierre and a few other friends break into uncontrollable laughter at what Soldier Boy has just said. It is as if he has told a wonderful joke.

SOLDIER BOY: This George, who is he? What do you know of him?

And then . . .

CUT TO:

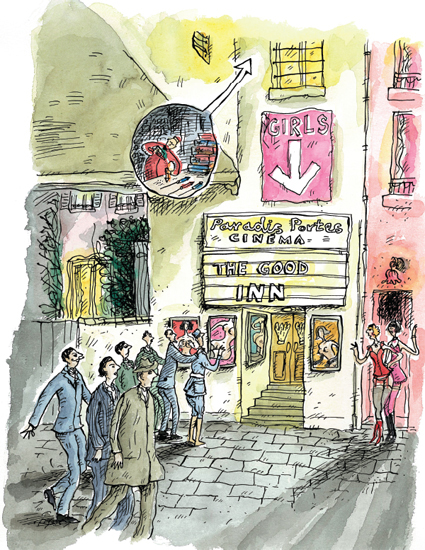

EXTERIOR/PARIS STREET—PIGALLE/NIGHT

And so then off they went with plans in place,

to remind their forgetful friend all his old friends’ tastes.

To show the celebrated star of Paris’s stage,

what he’s been missing, on his rise to fame,

a night that money just couldn’t buy,

these people who have made a mistake,

for this is not their famous George.

But a lost Soldier Boy.

The crew is all collected;

they congregate in a small square in the Pigalle.

Once they all heard of the plans, and the company that they would be keeping,

there was no one who would miss such an epic night.

From the film shoot, no longer atop his bike,

Pierre is in the lead, as is his leading lady,

who is kissing Soldier Boy’s sleeve.

First to join the party is Félix Fénéon, surprisingly on time, probably keeping count of minutes, Pierre suggests to Soldier Boy, with his latest time-bomb piece.

He’s escorting Irene Bordoni; she is the star of the latest musical playing at the cinema down the way,

a beautiful French-born actress

who has made it in the USA.

Next to arrive is Jacques Tati; he isn’t anyone yet,

but he has big plans, so he fits right in among this set.

He strolls up to the bunch as yet another body arrives,

a friend of the director’s named DALÍ,

who has a live rooster at his side.

Off they go into the night. The first stop is very close

but also quite out of sight.

Down an alley, through a door, up a staircase, and then down two more.

Drinks are served, the color green;

the place is packed, and sweet smoke fills the air with nowhere to escape.

They pour the liquid into Soldier Boy’s cup,

he drinks it up,

and they fill it over the brim,

again and again.

But there is no time to waste, there are still many more stops, so they have to keep up the pace. Back down the alley, through the door, down the staircase, and then up two more.

They are walking so fast that Soldier Boy loses his step, toppling over Dalí and his rooster, whose name, he is told, is Gissette.

Up into the air the rooster flies while Dalí shouts, “Get back here, you dirty cock, you!”

Everyone watches as it hovers above,

while Dalí screams insults and the others try to talk it down from its perch.

It has settled on a windowsill three stories up, of a flat being rented by a friend of Fénéon’s, who shouts out, hoping he will hear,

to this painter named Chagall whom he met through Seurat,

whose neo-impressionist paintings he championed by naming the lot.

He shouts up for his peer to help out

and catch the wild rooster that’s flailing about.

The window frame opens and a hand grabs its leg,

but the bird is a fighter and flies way up high,

carrying poor Chagall out until he is almost floating in the sky.

Getting control, he pulls the bird in, and brings it down to the

street,

and joins the party,

which is already on to the next scene. The next stop is something peculiar,

an activity that only these strange men knew;

it seems that George came up with the plan when he refused to go

to the parts of town that other gentlemen do.

In lieu of the usual “late-night entertainment”

he had found a way to visit the latest peep show at a more civilized venue.

They all stand in front of the Hotel des Deux Mondes, and the men serenade the women with their usual song.

Which translates in English to . . .

This is always the part of the night the ladies will not entertain,

so they wait in the lobby drinking cheap champagne.

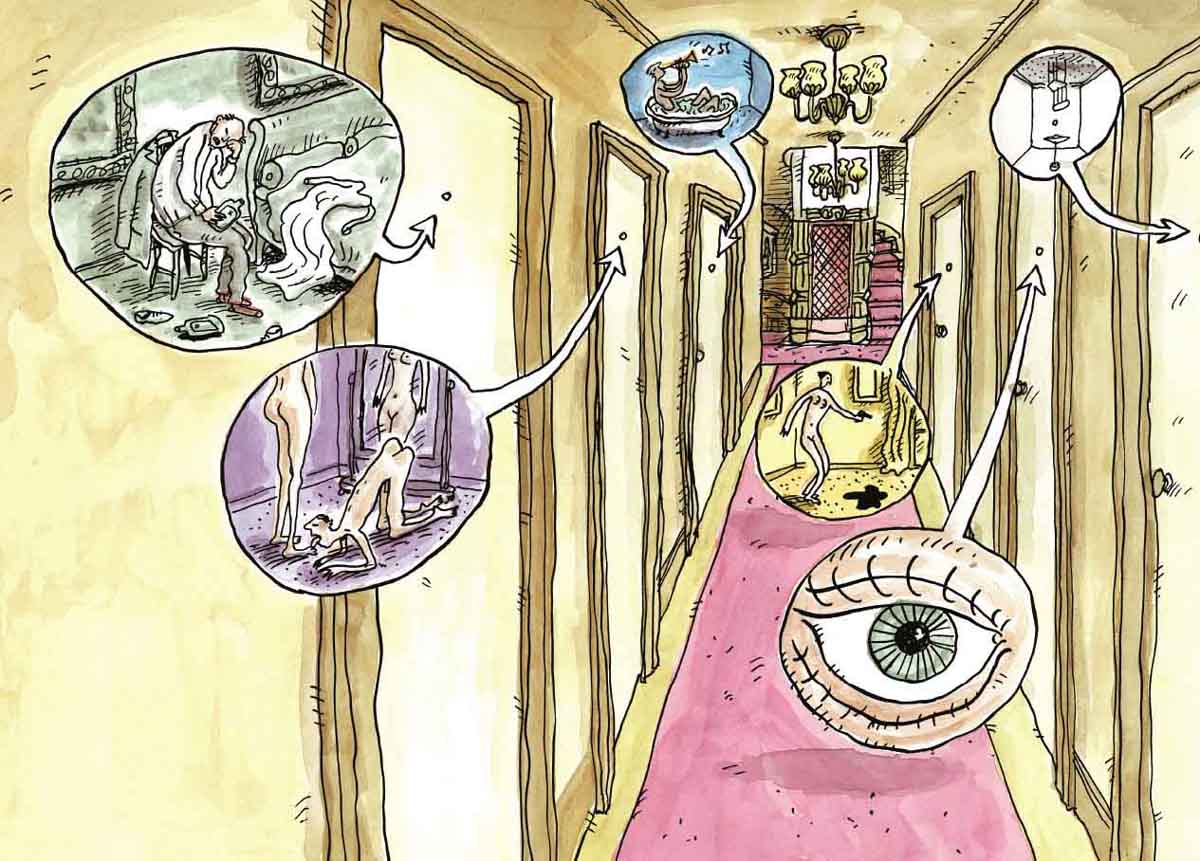

The men push Soldier Boy up a grand flight of stairs,

down a long hallway, where the guest rooms line the walls.

They continue their drunken singing as they each march

down the halls,

taking their stand, in front of a door that they choose,

lined up along the wall.

Soldier Boy watches as the men all bend down

and look into the rooms, into the other world on the other side

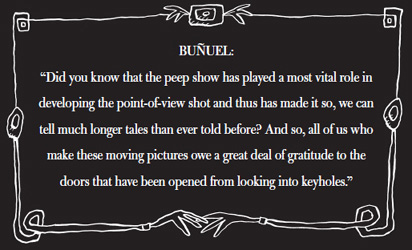

of this aptly named hotel. Fénéon is the first to describe what he sees:

an older man is crying onto a letter that he reads.

He assumes that he has been left by his much younger bride

who ran off with his stepson,

who both soon will die.

Next is Pierre, who explains what he sees:

a woman stands naked, above a man on his knees.

She stares at herself in a mirror while he kisses her feet.

She walks away from his advances as he arrives at her thighs.

He pants like a dog as she wishes him a good night.

Tati sees a musician just returned from his nightly session,

preparing a bath while starting a phonograph.

Now naked, he carries his trumpet under his arm,

and sitting down in the tub, he begins to play along.

Buñuel watches Soldier Boy with a look of concern;

George doesn’t seem like himself, he hasn’t even looked in his hole.

He motions for Soldier Boy to look in on the show.

The director then bends down and gives it a go;

a woman is dancing with an invisible man,

and then pulls out a pistol

and shoots him in the head.

Soldier Boy peers through the hole in his door; to his surprise an eye stares right back at him.

SOLDIER BOY: I’m looking at nothing. Someone is looking at me!

He backs away from the troublesome view;

the others have joined him and each take a turn.

Each man returns with the same upsetting news:

no one is there, just a room with a view.

They then make their way to the basement salon,

where something peculiar is always going on.

They each take a peek into the most secret room in the place;

tonight is no exception, you can see it on their delighted faces,

peeking through the keyhole on this very night. Savate is this

evening’s entertainment,

which is a French game of foot fights.

Off they go to the next stop on the way

toward the final surprise, which is a secret they save.

Into the streets the whole caravan screams,

riding the city like it’s a roller coaster,

up then down, to the darkest place in Paris at this time of night.

Before the picture shows, this was the late-night attraction to beat,

but now no one goes here,

except for those who care for the dead, are looking for thrills,

or are just wrong in the head.

INTERIOR/PARIS MORGUE/NIGHT

The morgue is located within a short walk of their next destination,

Les Deux Magots!

The bodies are lined in rows up and down;

the revelers walk them in a somber silence until . . .

Fénéon as usual is ready to entertain, by standing on the corpses’ tables and stating a claim, that death is something the living should embrace, as the living since birth are from the very start well on their way to the very same place.

Pierre steps up next to Soldier Boy, who appears to look very sad and has since gone pale. He puts his hand on Soldier Boy’s shoulder and speaks under his breath.

SOLDIER BOY: Please, oh, please, if you truly are my dear friend, take me away from this place.

EXTERIOR/PARIS STREETS/NIGHT

They ascend up out of the darkness,

onto the brightest Paris street,

brighter than any other,

from here to where the sea and the Seine both meet,

on to Montmartre, down the boulevard des Capucines.

And there in the distance, touching the sky, is the tower that Eiffel built,

and all around Soldier Boy, the streets are alive,

the lights blinking almost seem to electrify,

the very atoms in the air, and the colors, the colors everywhere,

so rich and vibrant, one might think one could taste them.

Soldier Boy suggests such a thing to Tati,

who quickly tests the theory on a piece of poster

that he rips from the wall, licks and then eats.

Soldier Boy stops short and sees the image torn in two:

it’s a woman whom he’s sure he once knew.

He pulls out of his pocket, the picture from Pirou,

that he bought off of a peasant,

what seems like years ago.

Yes, it is her. The woman from the picture,

the woman whom he pursued.

She is so much older now that he almost did not connect,

that this was the once-famous Nickie

whom he had seen through the Good Inn’s hole.

Fénéon has stopped and watches his companion,

wondering about much the same thing as the others:

There is something odd about this George, but what?

Now standing beside Soldier Boy, he speaks . . .

Fénéon speaks softly, wary of passersby; out in the open this man seems less at ease.

FÉNÉON: Shall we go there?

SOLDIER BOY: Oh, yes! Please!

CUT TO:

INTERIOR/LES DEUX MAGOTS/NIGHT

On to the next stop that was in the plan,

Pierre, Soldier Boy, and the others make their entrance so grand,

and take over the best seats in the house

next to the dancing girls and the piano man,

with his three-piece band.

On top of the stage, is the latest take on the Paris cancan.

Everyone is here tonight, everyone is out and about.

First to join them at their table is Alice Guy,

the first woman director, who has since retired.

Following Alice is Jacques Prévert,

a celebrated young poet

and member of André Breton’s Rue du Château group.

Across the room sits the son of Renoir,

who sold some of his father’s paintings

to finance his latest flick.

The food and drinks arrive, and Soldier Boy eats until he is satisfied.

Never has he felt like this, so full, and so alive.

He impresses almost all attending with his knowledge of moving

picture history

and all the facts that he’s collected.

All but Félix Fénéon have taken to their new George,

but Félix senses there is something off about their little Soldier Boy.

Suddenly, Jacques stands up drunk and announces that he has something to say.

His friend André Breton has pronounced this, and he wants everyone to listen,

because it is a matter of fact that

“the man who can’t visualize a horse galloping on a tomato is an idiot!”

The night is capped with song and dance,

a digestif, and in the back parlor, a game of chance,

where cards are dealt around a table.

What Soldier Boy loses is won by Pierre,

who shares his winnings with everyone there.

As Soldier Boy walks back across the wide open space,

passing the singing and the dancing,

heading for his new friends, at the best table in the place,

a hand grabs his arm and he jerks to a stop,

and looks down at the table where his arm has been caught.

An older man whom he seems to recognize,

by the shape of his head

and the curls on his mustache’s sides.

But still he can’t place the face, which he was having a hard time doing,

because he saw it through a hole,

in a different time and place.

Léar has been dining far across the room, studying Soldier Boy,

while catching up with his special dinner guest.

Bernard Natan has come far from his Romanian days;

just that very week he purchased Pathé and now owns the largest film

production company outside of the USA.

As Léar smiles and nods at all his old partner’s newest exploits,

he is wondering if he will ever rid his mouth of this most bitter taste.

Why is he not in his old business partner’s shoes,

walking on air, after paying his dues?

A little film he believed would bring him fortune and fame,

shot his lead actor to stardom and made Natan his name.

But no one wants to remember

the film that is to blame.

What a reunion, this couldn’t be a coincidence;

Léar has a few words to say to George, who has forgotten the man

who gave him his chance.

And now that actor is standing in front of his face,

wearing a costume for a film he was in,

about an inn, from a plot that Léar did spin,

although even he would admit, it was thin.

Has Natan planned this little twist?

Suddenly Léar’s worst returns, and he is sure that the joke was

planned,

at his own expense.

And then he speaks . . .

SOLDIER BOY: Costume? These are my clothes. I’ve worn them since I left my post. Do we know each other? I’m afraid tonight has taken half my wits!

And then Léar laughs and speaks again.

And then Soldier Boy pulls back his arm,

stepping away, both offended and alarmed;

who is this man speaking to him so unkindly,

what has he done to him, in this or in some other life?

Léar then stands up prepared for a fight;

Natan grabs his arm, holding on tight.

Only too schooled in this man’s brutal force,

he doesn’t want talk of a scene,

especially with all that he has to lose.

Soldier Boy backs away and returns to his crew,

while Léar watches them pay the bill and head for the street.

Léar turns to Natan with apologies

and sits back down in his seat.

Natan clears his throat and speaks.

Léar smiles at Natan and then pats his mouth with his napkin and places it gently on the table before he quietly responds.

“I am just a grain of red sand, my old friend.

I travel on the sirocco wind,

blown all the way from Africa,

where I meet with La Tramontane.

From there I travel through the Rhône Valley,

where I find these lost souls—my creations;

they travel through light, which is itself quite a feat,

but unlike light, the wind can go where light cannot,

to that place where the truth always hides:

into the dark.”

CUT TO:

EXTERIOR/STREET/NIGHT

The group is thinning.

The ladies have said their good nights,

but the evening is not yet over.

There is still one more stop to make.

Leading the way is Fénéon, walking at a brisk pace;

Buñuel can barely keep up,

with his cigarette hanging off his face.

Up the boulevard de Bonne Nouvelle

to passage de l’Opéra

and through a little alley into a courtyard

where, once upon a time, a magician named Méliès

had a cinema in the open air.

Across a connecting courtyard

past a building that once was

a little cinema founded by none other than Monsieur Léar and

Monsieur Pirou.

Past the famous Grand Café, in whose salon the Lumières

projected their proudest day.

Finally, they turn a corner onto the boulevard des Capucines,

in the Ninth Arrondissement,

to the number twenty-three.

Above them, lighting up the night,

is the name of another once-famous site:

![]()

Here, Fénéon explains, is where the founder of the Moulin Rouge

built a movie theater, the biggest at the time,

with a small basement theater below,

also owned by Monsieur Léar and Monsieur Pirou.

Once the grandest show palace,

where everyone performed,

even Nickie Willy, before her light went out.

But now the place has seen better days,

the entrance to it has been razed,

all that’s left is its grand old sign,

which the city pays to keep lit up,

in place of lighting other stuff.

Around its corner, the gang goes

into an alley that Soldier Boy knows.

From some frightful dream where he was pursued

while searching for his other half, and for his second Nicole.

A shabby marquee flickers and buzzes,

the entrance to Léar’s old theater below the Olympia has suffered many abuses,

behind the new Paris that, like ivy, has covered up and overgrown,

this little lost house of strange cinematic uses.

Just next door, the red salon sits,

a place some call, a house of sin,

a row of small rooms are reserved,

a few women for so many men.

And above the house where these women work,

an old man from the Orient assembles fireworks of every sort.

Two for three francs, or four for seven.

Business has been slow, so the room is very cramped,

a leak in the pipes has made the fuses all damp,

walls of his creations on all four sides,

an explosive combination, that up until now he has been able to

hide.

In the old theater below, conveniently placed,

a movie is on the marquee to play at the top of each hour,

to give the men a push in the right direction,

to pay for a room and a woman’s hourly affection.

Soldier Boy looks up to read the marquee,

the film on the bill is about to begin, it’s a silent two-reeler called