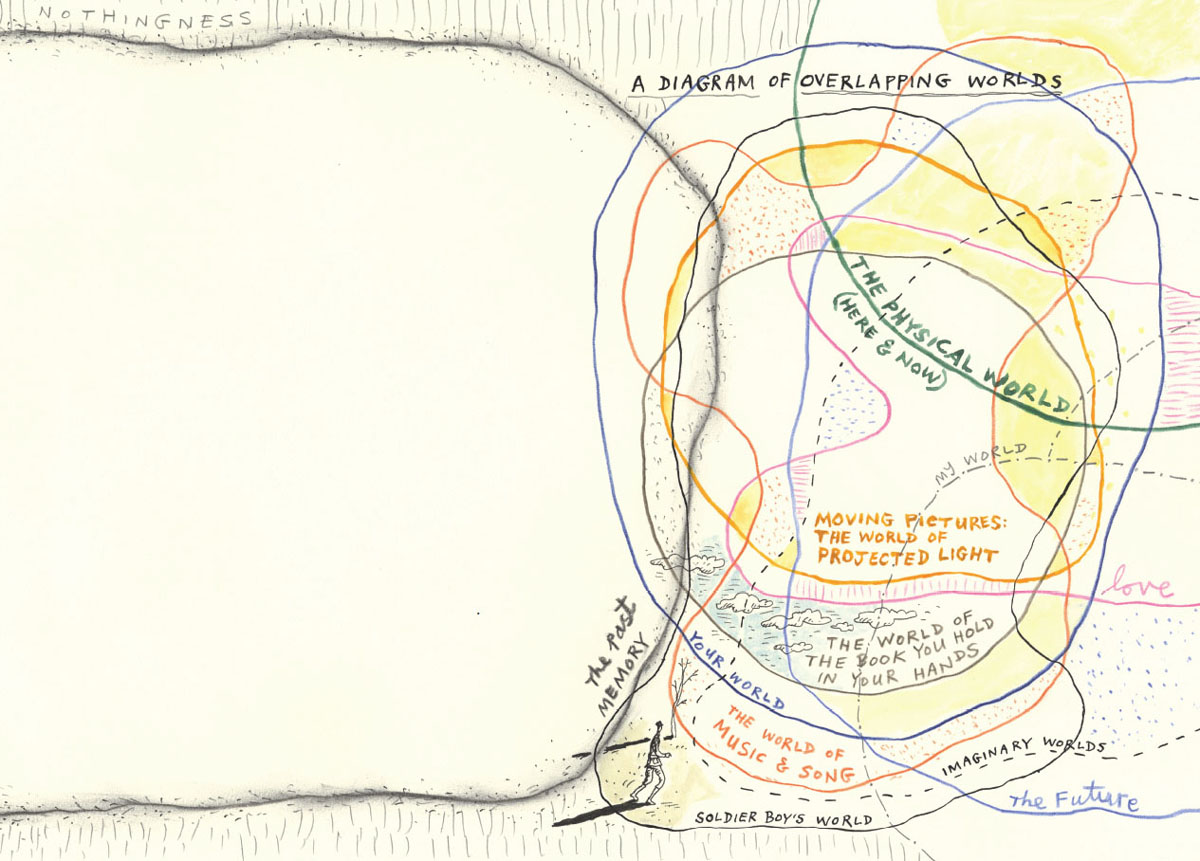

A few years ago, my friend Charles Thompson (a.k.a. Frank Black, a.k.a. Black Francis, front man and founder of the band the Pixies) sat down with me at a little French café on the East Side of Austin, Texas. He was right in the middle of his Pixies Doolittle twenty-year anniversary tour. I’d brought him here because the man loves all things French. This was the same guy who named his fourth Pixies album Trompe Le Monde, after all, and who would find any excuse to get to Paris. So being the Texas barbecue-bred boy that I was, I had to do some research in order to find a passable French experience in a city that celebrated smoked brisket and ribs. As we took in the aroma of our espressos in the warm and inviting bistro vibe of the Blue Dahlia, I asked him what he wanted to do next. Charles always has exciting new projects in mind and I am always amenable to the cause. Charles and I had become friends over the years, as my first two books concerned topics of interest to him. The first was a book about the Pixies and the second a book about a man named Peter Ivers, who wrote the title song for David Lynch’s Eraserhead.

Aside from an affinity for France and making music, Charles has always loved the cinema. Sitting at the café, he began to tell me about how he had been struggling to find the right way to bring new Pixies material into the world after it had been absent for so long. He wanted to create something musically that was completely different and new. He felt that if a filmmaker would come along and ask his band to do a soundtrack for a cool movie, that might be the answer. I had just finished telling him about my latest writing project: a puppet rock-musical movie about a world where people live symbiotic relationships with puppets by sharing their subconscious minds through a device called a “Flip-Chip,” invented by a master puppeteer in a world that now hated puppets. He was fascinated by the completely made-up original world and all its possibilities.

As the conversation progressed, he divulged that he actually had an idea for a film. It was the story of the first pornographic movie ever to include a narrative.

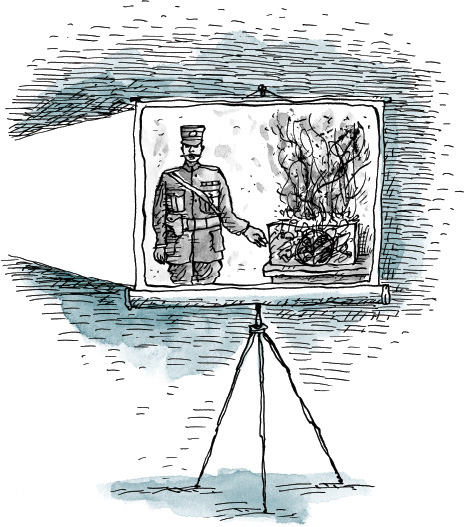

He was inspired by a film he’d heard about called La bonne auberge (The Good Inn). Set in 1907, it had the meagerest of plots: a soldier goes to an inn and meets the daughter of the innkeeper and they have a lot of sex. Charles had become fascinated by the idea of filling in the blanks to the soldier’s backstory, and in an early attempt to find new Pixie-ish inspiration he had even recorded a few demos for songs pertaining to the story, describing it as sort of a soundtrack “song cycle” about a character named simply Soldier Boy. It was at this point that I interrupted him and said, “Wait a minute, you mean you’ve already started writing the soundtrack to this movie?”

From there, everything fell into place.

“Charles, why not write the soundtrack to the movie first? Who says you can’t write the music before there’s an actual movie to score? If you want to make a movie, you should start with what you know how to do best: the music.”

There was a moment of silence while Charles mulled this over. Then he asked me to help him write it. “Write what?” I asked.

“Our movie,” he responded.

Now we both took a moment of silence to contemplate the exchange that had just occurred and he asked me what else I had been up to. I told him that I had recently by chance invented and opened the world’s first mini urban drive-in movie theater, which I’d built in a back alley way on the East Side of Austin. We projected on the wall of a church, led by a mariachi band. Charles lit up like the sun: “Wait, you have your own movie theater?” In the purest form, this is Charles, getting excited about a little oddball thing and then being fascinated to the point where he would request that I take him to see it after his show.

So it was eleven thirty P.M. on a Thursday night and I picked Charles up in the back of the theater where he was performing Doolittle in Austin, with a two-hour window before his bus left for the next stop on the tour. We drove across town and pulled up into the alley of the Blue Starlite, my twenty-car drive-in movie theater. I flipped the power switch and the lights illuminated around the little back-alley drive-in, turning the dark East Side lot into the tiny cinematic wonderland I had described to him. Charles was thrilled. I switched on the projector and the vintage drive-in movie ads started playing on the wall that I had painted with a fairly authentic-looking drive-in movie screen. We just sat there until he had to leave, talking about movies and how he’d always dreamed of having his own movie theater. In retrospect, it really was the perfect start to this project. I discovered later during my research for the book that Georges Méliès had one of the first outdoor movie theater spaces in Paris, back before the great movie palaces sprang up and left him and his work in their shadows.

Charles loves movies, movie theaters, and music, and man, does he love France. So in many ways The Good Inn is the ultimate love letter to all of the things that fascinate him.

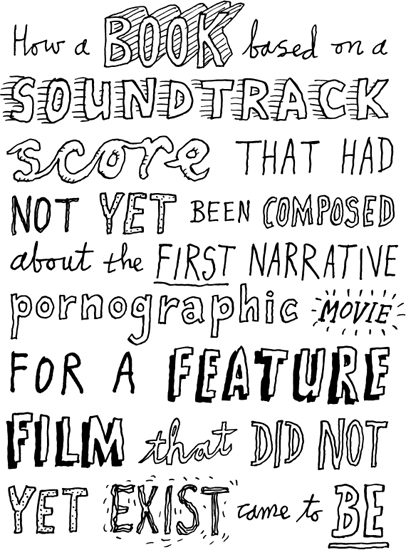

So how did it become a book? Following a few of our “brainstorming sessions,” I called up Steven Appleby, who did the very cool rocket drawings for the cover of the Pixies’ fifth album, and I asked him if he would do some illustrations to help us with our movie pitch. How cool would it be, I thought, to have the illustrator for Trompe Le Monde storyboard our movie! Appleby jumped on board and began drawing away, and Charles loved every panel he created. That’s when the idea of an illustrated novel based on our screenplay idea came about. And thus, the book you hold in your hands came to be.

Over the next year, we delved deeper into the history books to find out anything and everything we could about The Good Inn and the men who first got their hands on a moving-picture camera. We wanted to know how these very early “blue movies” were made. As you can imagine, they were not considered national treasures or important French history. Many of them, including The Good Inn, were lost in time except for a few film frames.

One thing that seemed to happen frequently was that popular early pornographic films were remade and then renamed, to the point where it was nearly impossible to track down their origins. There are actually a few versions of The Good Inn that are described on the web, but the only moving images we uncovered were from a remake. This is available to watch online. The one still image that we were able to find depicted what we believe was the style and feel of the original film. As Charles describes this image, “It is strangely innocent, the actors don’t seem self-assured in the least, they almost look like deer in headlights, they are not acting, it’s almost as if it is real.” The remake depicts a “musketeer” and is full of lighthearted sexual innuendos. This is more in line with later pornographic films, which would have been far more assured of themselves than, say, the first narrative pornographic film ever shot. This was an exciting discovery, but also frustrating, as we were hoping to see the original film that we were creating an entire world around. So I switched gears to try to find as many books about the first pornographic filmmakers as I could. I quickly discovered that there were none. Another setback for sure, so I decided to concentrate on learning everything I could about the “legitimate” filmmakers of this time (1882–1915) and to see whether within their stories there were any hints or clues about the peers who might have made The Good Inn and other movies like it. And that’s exactly where I found them, hidden in the paragraphs of other people’s stories. So I told Charles my discovery, and soon he was sending me articles and biographies of French actors, artists, terrorists, politicians, producers, and directors that at some point or another had crossed paths with the same strange lost (or buried) names who in part created the first blue movies.

As a result of all of this detective work, many of the events that take place in The Good Inn are culled from real events in history. A number of actual people were also used as templates for characters, such as our antagonist Léar, whose history in film and on the planet is fairly well documented up until the early 1900s, when all mentions of him mysteriously come to a halt, as if he just vanished, or was erased, in time. Based on historical research, we interpolated to the best of our ability the most likely scenarios for what we felt would or could have happened.

Similarly, while many of the linking narrative elements are clearly inventions of creative interpretation and made up to tell the story that we wanted to tell, they are based on actual historical truths, such as our female protagonist Nickie Willy, who is in part based on Louise Willy, a performer in the peep show Le coucher de la mariée, as well as Louise Weber, a cancan dancer at the Moulin Rouge and a muse of the affichistes of Paris. As well, we made occasional historical guesses and mixed science fact with a shot or two of science fiction, and after two years, we had completed the narrative. When people asked me what it was like, I described it as the Gone with the Wind of French cinema’s blue movie history if it was written by the Pixies and directed by David Lynch and Terry Gilliam.

Above all else, Charles is a storyteller. Not just a storyteller but a collector of stories, a real honest-to-goodness modern-day troubadour, wandering through this dimension collecting the oddest oddball stories and turning them into rock ’n’ roll. I grew up listening to his two-to-three-minute musical tales, surrounded tightly by clustered atoms of quiet cool to loud choruses, of entire worlds that left my friends’ imaginations, as well as my own, spinning with images of aliens on lonely highways. There were proud Spanish dancers in seedy bars, monkeys going to the eternal kingdom, and biblical bloodbaths that somehow seemed sexy.

I always wondered what this man would do if he had more than three minutes to tell a story, and through our collaboration, now I know.

Charles did end up writing amazing new Pixies material. Released in parts over 2013 and 2014, a few of the songs’ hooks were actually repurposed from instrumentals from the original recording sessions for the Good Inn demo that Charles, Joey, and David created together. Seven of the Good Inn Demo Songs lyrics were used as inspiration for this book and are “musical scene centerpieces” in the narrative.

What follows is an illustrated novel, based on an in-the-works soundtrack, for a feature-length film that has yet to be made, about the first narrative pornographic movie ever made.

And now, without further ado, let’s dim the lights in the theater. We are very proud to present to you our film, The Good Inn.