With the sun flashing on her oarblades, a Roman trireme pulled steadily into one of the Channel ports. The waiting soldiers and civilians saw the pennant fluttering from the mast and gave up a great welcoming shout: ‘Imperator, Imperator!’—for aboard the vessel was the man who was to beget one of the most impressive and enduring Roman military works to survive into modern times: Publius Aelius Hadrianus, the Emperor Hadrian.

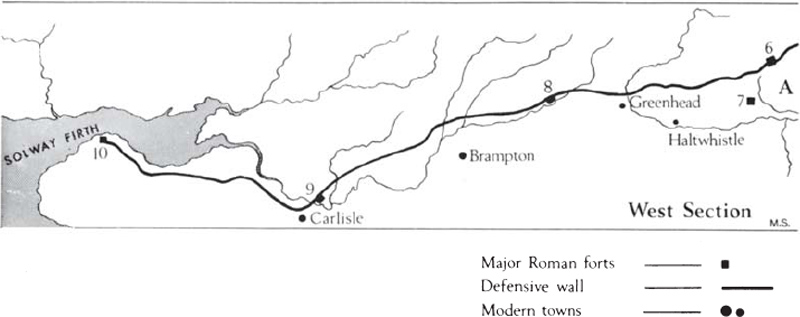

A fragment of the structure of Hadrian’s Wall at Hare Hill; the core is original, and the facing stones are restored.

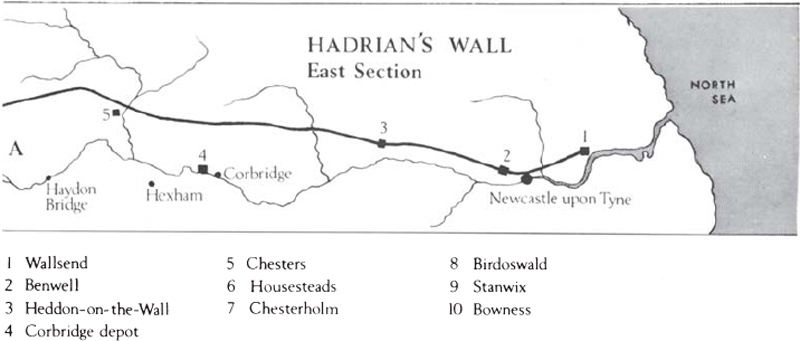

This year of 122 was the first time a Roman Emperor had set foot in the Province of Britannia since the invasion in A.D. 43. Hadrian, an intelligent and energetic ruler, had come to inspect the Province in person; and apparently its security in particular. No doubt he had read many reports concerning the damage caused by marauding tribesmen crossing from what is now Scotland into the Province, pillaging, destroying and encouraging others within the Roman pale to resist the occupation. And so Hadrian decided—in the words of his biographer—‘to build a wall to separate the Romans from the Barbarians’.

While it has been considered that the Wall was built partly, or even largely, to give legal definition to the extent of Roman rule, its major function was, without any doubt, to secure the northern frontier against the Scottish tribes. Incidentally, it did produce the effect of a powerful chain of military installations which could readily be supplied from the sea in the event of an uprising to the south.

There remains some dispute as to the exact year in which the building of the Wall commenced; some believe it to have been begun in A.D. 120, and subsequently delayed by disturbances in the Province which necessitated some changes in the original plans. Therefore the following description of the building of the Wall is partly open to question.

The initial concept was the construction of a stone barrier, ten Roman feet* in thickness, from Newcastle in the east to the River Irthing. The remaining distance from the Irthing to the Solway Firth on the west coast was to be fortified with a turf-and-timber rampart, twenty feet wide at the base.

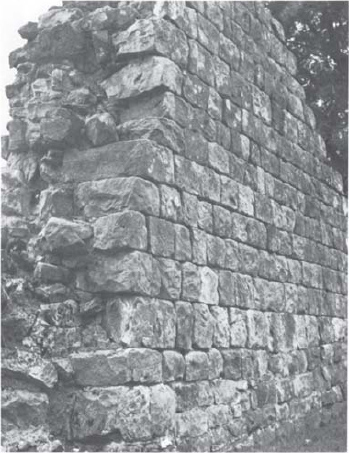

The floor of a large granary at the supply base of Corstopitum (Corbridge) just south of the wall. Finds at Corbridge have been of great importance to our understanding of Roman armour.

The fortifications were furnished with mile-castles at regular intervals of one Roman mile, with two turrets in between at distances of one-third of a mile. On the north side of the Wall, a ditch approximately twenty-seven feet wide and ten feet deep gave greater strength to the barrier, except where the Wall ran along the top of precipitous natural features which made such excavation superfluous.

The sequence of construction appears to have been first to site and build the milecastles and turrets, and then to link them together with a curtain wall. The fact that some of these structures were clearly intended to receive a curtain wall ten feet in thickness (and indeed foundations for walling of that dimension were laid) but in the event were completed with a narrower superstructure, shows that an increase in speed of construction became necessary. One explanation may be found in that the original plan of the defence works was altered to include a number of forts along the line of the Wall, requiring the demolition of already completed fortifications.

The belated inclusion of forts on the Wall itself may indicate that the Romans had encountered opposition from the Scottish tribes during the initial stages of construction, and therefore an immediate and permanent military presence was found to be expedient, instead of summoning at need troops stationed in the forts along the Stanegate road as much as a mile to the south. Conceivably both these factors could have influenced the decision to lighten the Wall structure, for the building of unforeseen forts of quite large dimensions would have badly disrupted the programme at first laid down.

The building of a turf-and-timber rampart along the western sector of the frontier, supports the theory that the rapid establishment of an impenetrable line was of importance. It is probable that the use of turf and timber—semi-permanent materials at best—was also caused by the absence of suitable building materials in the immediate area, there being no limestone source west of the Red Rock Fault running north to south near present-day Brampton. The turf rampart was, however, later replaced with stone when time permitted—certainly before the end of the 2nd century.

The forts were placed, where practicable, astride the Wall, with three double gates to the north of the Wall line. Although there is disagreement about the precise purpose of the gates, they very clearly presented a considerable deterrent to any would-be attacker, who could easily find his means of retreat cut off by cavalry making rapid sorties from the forts.

Behind the Wall and close to it ran the ‘Military Way’, a road some twenty feet wide, and to the south of that, at varying distances, lay the Vallum, a flat-bottomed ditch averaging twenty feet wide at the top, ten feet in depth and eight feet wide at the bottom. The spoil from the excavation was deposited on either side of the ditch, about thirty feet back from the edges, providing continuous ridges about six feet in height; access to the Wall was by gated causeways.

The purpose of the Vallum appears to have been to mark the limit of a strict military zone behind the Wall, presumably so that there should be no impediment to rapid troop movement on the Military Way. Though this was the primary function of the Vallum, it would have presented a considerable obstacle to any hostile force approaching from the south, and could have been made even more defensible relatively easily in case of need.

Skilled construction work was carried out by surveyors, engineers and masons drawn from three legions: Legio II Augusta, the newly-arrived Legio VI Victrix Pia Fidelis and Legio XX Valeria Victrix (XXth Valeria had been awarded the title ‘Victrix’ for the legion’s part in putting down the disastrous Boudiccan revolt in A.D. 61). As each century completed its allotted section of the work, an inscribed stone was set into the Wall or other structure to record the fact. A considerable number of these building stones have survived and may be seen preserved in museums along the Wall—Carlisle Museum possesses some thirty-six of them, which show clearly that not only legionary infantry were engaged in building the defence works. A rather extreme example, thought to have come from the Wall near the Birdoswald fort, is inscribed PED(ATURA) CLA(SSIS) BRI(TANNICAE)—‘The length in feet built by the British Fleet’—presumably marines rather than sailors. Others bear clear legionary inscriptions: LEG(IONIS) II AUG(USTAE) COH(ORS) VII SU(B) CU(RA) . . .’—‘From the second legion Augusta—the Seventh Cohort under the charge of . . .’. The inscription is incomplete, but was found at the High House milecastle, which would have required the attention of highly skilled hands for its construction. Indeed, one may say that most if not all of the curtain wall foundations and complete buildings such as milecastles were the work of the legionaries.

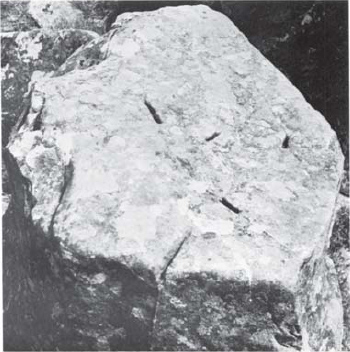

Simpler operations, the Vallum for example, probably employed mainly Auxiliaries for the actual excavation work; a stone found about 200 yards to the south of the Vallum is inscribed C(OHORS) IV LIN(GONUM) F(ECIT)—‘The Fourth Cohort of Lingonians built this’. It does not appear that the same can be said with any certainty of the ditch to the north of the Wall, which must have presented a real challenge on some stretches. This was certainly the case at Teppermoor Hill, known as ‘Limestone Corner’. There the regularity of excavation was interrupted by an outcrop of hard basalt rock, which required considerable effort to remove. Indeed, the operation was never completed: a large column of rock remains in the centre of the ditch with holes cut into the upper surface in preparation for splitting the mass. Perhaps the Romans considered, as seems the case today, that the work done had achieved a perfectly adequate defence and no further effort was required—attempts to cross the ditch at that point with any haste carry a guarantee of at least a broken ankle.

A building or marker stone from Hadrian’s Wall, possibly from the first period of construction. The inscription refers to the Cohort under the command of Centurion Flavius Civilis, using the conventional abbreviations found in Roman inscriptions. (Chesters Museum)

The milecastle should really be considered as a fortified gateway, probably manned by no more than sixteen men, possibly less. While various suggestions may be made as to the precise purpose of these structures, it seems wholly reasonable to regard them as points through which a Roman force could gain access to the territory north of the Wall without losing time or tactical advantage by moving as far as the nearest fort. However, it must be noted that some of the gateways are sited above quite formidable escarpments—a good example is at Cawfields—and one can easily imagine cavalry coming to grief in attempting a foray.

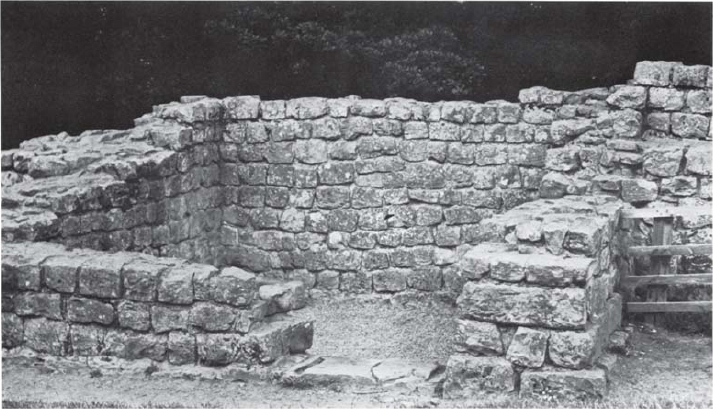

The remains of a Wall turret at Brunton near Chollerford, possibly the work of Legio XX Valeria Victrix.

No doubt the milecastles later became no more than openings in the Wall when the Scottish Lowlands were annexed and the frontier moved north to the Forth-Clyde line, the Antonine Wall; at no time does there appear to have been any attempt to seal them off, and it may be assumed that they reverted to their original military function once the Lowlands were finally abandoned under Caracalla in A.D. 211.

These small guard towers provided sheltered observation points, and a means of access to the Wall walkway; they may also have served as signal stations at certain places where visibility is obstructed by the unevenness of the terrain. Since there are no signs of there having been stone stairways within these structures, it is assumed that access to the walkway level was by ladder.

Unfortunately there are no remains or other information from the Wall itself to enable modern eyes to reconstruct, with complete accuracy, these or any of the other upper parts of the defensive works. However, information from other sources shows clearly that the Romans employed standard systems of construction, even if these varied slightly from legion to legion, and it is upon such sources that one is obliged to draw in order to gain an impression of a turret’s original appearance. Opinions differ: some authorities believe that the turrets had either pitched or pyramidal roofing, following the signal towers shown on Trajan’s Column, while others declare for a flat roof with a castellated parapet, which would have made signalling by either cresset or semaphore easier. The true appearance will remain hypothetical until more concrete evidence comes to light.

Housesteads Fort (Vercovicium), one of the best-known excavated sites along the Wall: (A) Commander’s house (B) Barrack blocks (D) Headquarters building (E) Granaries (F) Workshop (G) Stores (H) Hospital (J) Latrine (K) Ablution block. Many of the functions of the buildings are presumed, and based upon those identified in other forts.

Compact, sturdy and efficient, the forts are excellent examples of Roman planning; though here again one is obliged to draw upon other evidence for likely reconstruction, so badly robbed are all the Wall structures.

The most famous of the forts is that at House-steads (Vercovicium). This example differs from most others in that its long axis lies along the line of the Wall and has only one gateway to the northern territory. The fort was probably planned in this fashion because it is perched upon the Whin Sill ridge, with a very sudden escarpment immediately to the north and a steep slope leading up to it from the south; to have placed the fort’s long axis at right-angles to the Wall would have meant the inclusion of too steep a gradient within the enclosure. The building of only one double gateway to the north may indicate an intention to garrison the fort solely with infantry; the nature of the 2nd century garrison is, as yet, unknown, but in the 3rd and 4th centuries it was the base of the 1st Tungrian Cohort—a thousand-strong auxiliary infantry unit with irregulars in support.

The fort, covering some five acres, includes a surprisingly well-preserved example of a latrine building, which would have accommodated about twelve men at any one time. The deep sewer channels, which ran below the now vanished wooden seating, were flushed with water from adjacent stone storage tanks, the sewage draining away down the hill to the south of the fort. It might be supposed that there were an equivalent of ‘night soil’ operatives, probably fatigue parties, to deal with the product of a garrison of that size; for unlike the Chesters fort, there was no watercourse large enough to remove the effluent. It was clearly difficult enough to collect sufficient water to flush the latrine itself, the storage tanks being supplied with rain-water gathered from the roofs of the fort’s buildings and from a small stream outside the fort. It has been suggested that other forms of latrine would have been present, and indeed there must surely have been—a long hot spell of weather would have played havoc with the facilities that have survived. The same kind of earth latrines that one might expect in this regard would probably also have been in use at the milecastles, for some kind of sanitation would clearly have been necessary at the latter installations; probably very similar to the latrine slots fitted with wooden covers found at Waddon Hill of mid-1st century date.

To the south of the enclosure there grew up a small town called a vicus, approximately twice the size of the fort. The inhabitants of the town, some of whom were doubtless dependants of the soldiers, would have provided a variety of services to the men which would not otherwise have been available, and may also have traded with the peoples to the north. It was not unusual for such a settlement to attach itself to a Roman military installation, and apparently this was not discouraged; it would obviously have made the soldiers’ arduous life that much more tolerable. The term vicus appears to have referred purely to towns of this nature, the normal word for a town being oppidum.

The fort at Chesters—Cilurnum—beside the North Tyne began its life as a cavalry base, though the name of the particular unit is not yet known. Later in the 2nd century the fort was occupied by an infantry cohort, the 1st Dalmatians (I Delmatarum), but reverted to its original function in the 3rd and 4th centuries as the base of the 2nd Ala of Asturian cavalry, a unit originating from the tribe of the Astures in northern Spain.

Between the east wall of the fort and the Tyne, the remains of a military bath-house still grace the river bank. The baths were not merely for cleanliness, but also for relaxation, which may be the reason for the quite large changing room with its series of niches in the west wall, thought to have been receptacles for bathers’ clothing. Walking amongst the walls, it is not hard to imagine the rattle of dice, and the deep-voiced oaths and laughter as soldiers lost their pay.

Chesters Fort (Cilurnum) on Hadrian’s Wall: (A) Commander’s house (B) Barrack blocks (C) Stables (D) Headquarters building (E) Granaries (F) Workshop (G) Stores? (H) Hospital.

The building contains the normal range of rooms of varying temperature and humidity associated with all such Roman baths. There is also a latrine similar in design to that at House-steads, but smaller; effluent presented no problem here, as sewage was simply flushed into the river a few feet away by water from the baths.

On the opposite bank of the river part of a stone bridge abutment is still to be seen, where a timber bridge continued the Wall walk across the river to the fort. The large exposed stones show Lewis holes for lifting—a dovetailed incision, one per stone, into which an ingenious hook device was inserted and engaged as the slack of the lifting gear was taken up. The stones were very finely dressed, and show that either the legions contained some craftsmen of high ability, who for once were given an opportunity to forget the normal military requirements of speed and simple utility; or that specialists were brought in from outside.

While all the legionary fortresses were equipped with a hospital (valetudinarium), normally only the larger auxiliary forts contained such quarters, and usually on a smaller scale. The legionary examples consisted of sixty rooms arranged around a central cloistered court. The hospital was in the charge of an optio valetudinarii, under whom were the medici or doctors with their orderlies—medici ordinarii. Below that came the capsarii (a name derived from capsa, the round bandage container they carried) whose function appears to have been to give first-aid to the wounded on the field prior to their being taken to the hospital. One may expect that the medici ordinarii were capable of attending to relatively minor injuries, while more serious wounds were the responsibility of the medicus.

The changing room of the bath-house at Chesters, from the east; niches probably held the bathers’ clothing.

There must have been a very considerable variety of cases for treatment, not only as a result of combat, but also from disease. Very many of the grave stelae that survive—and these represent only a very small proportion of the actual numbers—belonged to men who died in their late twenties or early thirties. Unfortunately, the stelae do not often record the cause of death, unless it was in battle, e.g. Centurio Marcus Caelius, who was killed in the Varus disaster in A.D. 9; but it is not unreasonable to believe that many died as a result of relatively everyday ailments, and that others would have perished from septicaemia contracted from wounds. As advanced as it was for its time, Roman medical practice did not include such stringent measures of hygiene as those followed today.

The types of wound that were encountered as a result of battle would largely have been punctures and lacerations of varying degrees of severity. The method of extracting barbed arrowheads employed at least two sensible procedures: the use of split reed stems inserted either side of the missile to shield the flesh from the barbs as extraction took place and, in the case of broad-headed arrows, the use of a special instrument called ‘the scoop of Diocles’. This was a blade-like instrument, presumably wider than the barbs of such arrows, curled back at the lower end with an aperture pierced through the crook thus formed. The upper end was worked into two hooks as a means of gripping the instrument, which was inserted into the wound and manoeuvred until the point of the missile engaged in the aperture; both instrument and missile could then be removed simultaneously by means of the hooks.

The bath-house at Chesters Fort: (A) Changing and recreation room (B) Hot room — hypocaust (C) Hot bath (D) Hot room (E) Water boiler (F) Warm rooms (G) Cold room (g) Cold plunge (H) Cold bath (J) Latrine (K) Outflow to river (S) Stoke-holes.

The bridge abutment at Chesters, where the Wall crosses the North Tyne; in some of the stone blocks ‘Lewis holes’ are still clearly visible.

Other operations of greater consequence, such as limb amputations, would have been carried out in fort hospitals; the procedure, according to Cornelius Celsus in his work de Medicina, was virtually identical to that of the present day—although, of course, there was no anaesthetic. The use of drugs was also known and widely practised in the treatment of various disorders; though modern man would regard them as little more than herbal remedies, they were probably reasonably effective, always providing the diagnosis was correct. Naturally enough, being firm believers in unseen divine entities, the Romans accompanied sound medical treatment with much religious supplication; but basically, their approach to the maintenance of health was highly practical.

Diet in the forts differed considerably from field rations. Military sites have yielded large quantities of animal bones and bivalve shells, which make it abundantly clear that the soldiers ate precisely the same foods as the civilian population when not engaged in field operations. In the field, as one might expect, they were obliged to carry foodstuffs which would not deteriorate rapidly, and it is this fact which has given rise to the misconception that the Roman soldier was a vegetarian. Perhaps it would not be improper to conjecture that the field rations were supplemented with perishables gathered by forage, as well as grain obtained in that fashion; legionaries may be seen on Trajan’s Column harvesting wheat with hand sickles while on campaign.

Religious beliefs, however dark or ludicrous they may seem to many people today, played a very necessary rôle in the life of the ancient soldier. In a cosmopolitan army such as that of the Romans, a very large number of deities were duly reverenced. The State Gods of the Empire were present in all parts, especially Jupiter and Mars; no mere accident that the shield of the legionary, with which he struck down his foes, should so often have been painted with the thunderbolt of ‘Jupiter the Greatest and Best’. Besides these adopted Hellenistic deities, and probably a more powerful influence upon the soldiers, was the cult of Mithraism—an esoteric form of worship which originated in India and found its way to the Romans by way of Persia, albeit in a slightly altered form.

The cult appears to have centred around man’s age-old fear of the dark. To a soldier the dark is unnerving, since it provides cover for enemies; but to the Roman, the dark meant more than just the wrong end of a spear or knife, it was also the dwelling place of evil forces. Against these imaginings he sought protection from Mithras, whose numerous titles made him a suitable candidate to oversee any occasion when one of his initiates might require assistance.

Mithras, the Lord of Light, was engaged in a constant war against the forces of Ahriman, the personification of evil; and there can be no doubt that it was an uneasy recognition of the many similarities between Mithraism and the derivative Christian observance which brought about the desecration of the Mithraic temples after the official acceptance of the Christian doctrine by the Romans in A.D. 313. Many fine Mithraic sculptures survive, however, probably because adherents to the old religion hid them from the Christians. (A splendid head of the God may be seen in the London Museum, amongst other sculptures and artefacts from the London Mithraeum.)

A stone tablet erected by Legio II Augusta at Benwell. It shows the legion’s ‘birth sign’—Capricorn—on the left; a flag standard (vexillum) with a three-pronged shoe in the centre; and the legion’s badge—Pegasus—on the right.

Other aspects of spiritual protection and guidance may be found in the concepts of the genii and Augury. The genii were rather vague incorporeal beings who embodied the unity of any group of persons, however large or small. In the army these entities were embodied in the standards of a unit, and so the loss of one or more of these was considered to be the cause of dire consequences above the mere disgrace of permitting the enemy to make off with the unit’s insignia.

An interesting question arises in connection with the attire of the bearers of those sacred objects. Prehistoric cult leaders, or ‘magicians’ as they are called today, are known to have worn the pelts of animals for their ceremonies. Could the Romans, consciously or subconsciously, have been following a very ancient religious custom by clothing their standard-bearers in animal skins?

Augury, or divination, was of course very widely practised in the ancient world, as it still is today, and the Roman military was certainly no exception. While a variety of means could be employed for the prediction of future events, the inspection of a creature’s entrails appears to have been much used for that purpose. Indeed the practice continued long after the acceptance of Christianity: in the late 4th century, a unit was recalled from northern Britain, where the men had apparently been using the corpses of slain Picts in that ritual—though this was not the reason for their withdrawal.

Belief in an after-life, and the consequent likeli-hood of spirits returning to interfere with the living, appears to be certainly as ancient as the late Palaeolithic period and maybe older. To the Romans there was absolutely no doubt whatsoever; spiritual survival was a simple, unquestioned fact, expressed in the practice of ancestor worship. Thus when a person died, his heirs or other appointed persons were obliged to perform with due ceremony and reverence the disposal of the remains, and to maintain, certainly in some cases, propitiation of the dead man’s spirit, in order that he should not return and seek redress.

The ditch (fossa) of Hadrian’s Wall at Limestone Corner; and (above) a basalt boulder prepared for splitting, and then abandoned.

In the early Empire, cremation, with its obvious advantages, was the usual means for the disposal of corpses, the ashes normally being placed in a leaden container for burial (an excellent example is that of the Centurion Marcus Favonius Facilis in the Castle Museum at Colchester). In some cases—evidence of the maintenance of propitiation—a pipe protruded from the top of the container to above ground level, for the purpose of pouring libations directly onto the remains.

During the 2nd century cremation began to be replaced by the practice of burial. Precisely why this occurred is not yet clear, though the idea may well have spread from the Middle East, where that method had always been used on religious grounds. Troops and civilians from that region would doubtless have brought native customs with them to the western provinces and the Roman authorities, as was their habit, would have been careful not to interfere with such beliefs as long as they did not have an adverse effect upon order and discipline, and burials took place outside inhabited areas.

The remains of the right collar section of a lorica segmentata found at Newstead, near Melrose in Scotland.

With the rise of Christianity and its creed of the resurrection of the physical body, burial had become the normal practice by the 4th century. In fact the new religion does not appear to have been accepted by the military to any appreciable extent, the preference being towards doctrines advocating strength and prowess in war, despite the ultimate declaration of Christianity as the State religion.

* I ‘pes’ equals .962 foot Imperial measure.