During boarding in Denver, Jan Murray had been in A-Zone, first class, helping people to their seats and hanging up coats. She had noticed Rene Le Beau, the newest hire, who was helping out in first class. Murray would always remember Le Beau. “I remember how pretty she was, and I remember her hair in particular. It was strawberry blonde and very curly and beautiful.” Once the flight had taken off and the lunch service was under way, Murray, a former registered nurse who was thirty-four at the time and had eleven years of seniority as a flight attendant, chatted with the younger woman. Le Beau was excited because she was going to be with her boyfriend that weekend and they were talking about getting married. The two women laughed together, enjoying the flight.

Indeed, they sensed a festive atmosphere in first class that day. Murray, a thin, youthful woman with bleached silver hair, had stopped to talk with William Edward and Rose Marie Coletta Prato and Gerald Harlon “Gerry” Dobson and his wife Joann from Pittsgrove Township, New Jersey. All four were dressed in Hawaiian clothes, laughing and enjoying the first class luncheon, the perfect ending to their trip to Hawaii. “They stay on my mind,” Murray said more than two decades later. “They were so having a good time.” The ladies were dressed in muumuus and their husbands wore Hawaiian shirts. “It was obvious they’d had a wonderful vacation. They were just very pleasant people. I think about them all the time.”

After lunch, Murray was cleaning up, standing in the galley between first class and coach, bending down to put a tray into the cart, when the engine exploded. Murray went to the floor reflexively. “It just was so loud that there’s no way to describe how loud it was. The plane was shaking pretty fiercely,” she recalled. “The plane was making sounds that I had never heard before.” When I asked Murray to describe those sounds, she made a noise like a siren wailing. She was hearing the hydraulic motors pumping all the fluid out of the system and overboard, as Dvorak, up in the cockpit, watched his gauges fall to zero. “It was very obvious that something was very, very seriously wrong.”

With her heart sinking, Murray continued cleaning up after lunch. When Jan Brown emerged from the cockpit and told her and Barbara Gillaspie and Rene Le Beau that they had lost all hydraulics, it merely strengthened her conviction that she was going to die. Murray had been serving lunch to two deadheading United pilots in the last row of first class on the starboard side. Peter Allen was in uniform. Dennis Fitch, by the window, wore civilian clothes. Murray had learned that Fitch was a DC-10 instructor at the United training facility in Denver. He was on his way home for the weekend. Fitch had first noticed Murray when she served his lunch. He had heard her lilting southern accent as the three chatted pleasantly.

Fitch was the oldest of eight siblings, and as such he had developed what he called “people radar.” He could spot a distressed person at a hundred yards, as he liked to say. Now he saw that Murray looked grave and worried as she rushed past. Fitch reached out, touched her arm, and stopped her. Murray leaned down. “Don’t worry about this,” he told her. “This thing flies fine on two engines. We just simply need to get to a lower altitude, and we’re gonna be fine.”

She leaned in closer and fixed him with a penetrating gaze. According to Fitch’s account, she said, “Oh, no, Denny.” She spoke softly so as not to be overheard. “Both the pilots are trying to fly the airplane, and the captain has told us that we have lost all our hydraulics.”

Fitch stared at her for a moment. He knew that wasn’t possible, but as he later put it, “A flight attendant is not a pilot.” She could not be expected to know anything about airplanes. “DC-10s must have hydraulics to fly them. Period.”

“Oh, that’s impossible,” Fitch told Murray. “It can’t happen.”

“Well, that’s what we’re being told,” Murray said.

“Well, there’s a backup system.”

“We’re being told that that’s gone too.”

Fitch thought about that for a moment and said, “Well . . . I don’t think that’s possible, but . . . would you go back to the cockpit. Tell the captain there’s a DC-10 Training Check Airman back here. If there’s anything that I can do to assist, I’d be happy to do so.”

Fitch watched Murray go forward as quickly as she could without alarming passengers. Fitch had been on full alert for a while now, and this new development was baffling and more than a little alarming. When the explosion occurred, he had finished his lunch and was having that second coffee that Susan White, tongue in cheek, had asked a nonplussed Jan Brown about far in the back of the plane. “The whole fuselage went very sharply to the right,” Fitch recalled. “That coffee cup is now empty. Its contents are in the saucer, and it’s all over the table linen. And my rear end, which is sitting in the middle of a leather seat, is now up against the arm rest to the left. It was abrupt and violent.”

As a Training Check Airman, or TCA, Fitch had conducted five days of training with a group of DC-10 pilots in Denver during the past week. When the engine exploded, he turned to Peter Allen and said, while mopping up coffee, “It looks like we lost one.” Fitch then felt the plane begin making a series of strange excursions across the sky, first up, then down and to the right in long, loopy spirals, and up and down again and again, like a boat on uneasy seas. With one engine out, they were supposed to be going down, not up. The right turns made it seem to him as if the number three engine on the right wing had failed, causing drag on that side. But the announcement said that number two quit. As a TCA, Fitch was exposed to every conceivable emergency, week in and week out, yet nothing he saw or heard made sense.

More than twenty years after Fitch had sent Jan Murray to the cockpit to offer his services, she described her experience there. “I went to the cockpit, knocked on the door. It flew open.” As she tried to describe the horrifying scene in there, she stuttered and stammered with the pain of remembering. “Th-th-the pilots were struggling so, it was just, it was incredible, the struggle that they were—just the visual of it was just—so frightening. It was like they were struggling to hang onto the controls. So I just hollered in there, I said, ‘You have a Training Check Airman back here if you need him.’ ”

Haynes didn’t turn around. He called out, “Okay, let him come up.”

“Immediately I closed the door, and trying to be as calm as possible, I walked back through the first class cabin and I leaned down to Denny and I told him, ‘They want you up there.’ ”

Fitch reached the cockpit, still thinking that the flight attendant didn’t understand the situation. But as the door opened, he recalled, “the scene to me as a pilot was unbelievable. Both the pilots were in short-sleeved shirts, the tendons being raised in their forearms, their knuckles were white.” As he closed the door behind him, Fitch’s eyes flicked over all the instruments and switches on Dvorak’s panel. He clearly saw that the motor pumps and rudder standby power were both armed. No rudder standby light. No bus ties (similar to circuit breakers) were open, the navigational instruments were working normally, and the plane had electrical power. Someone had already deployed a generator driven by air that was meant to pump hydraulic fluid in the event that the regular engine-driven pumps weren’t working. But the hydraulic gauges read zero and the low-pressure lights were on.

The plane was porpoising in a slow cycle, up and down, hundreds of feet every minute, even while both Haynes and Records fought the yoke to no effect. On the radio, Dvorak was pleading for help from the United Airlines maintenance base in San Francisco, while Records, breathing hard from his effort, used his knee to help force the yoke forward during one of the aircraft’s uncontrollable climbs.

Fitch later said, “The first thing that strikes your mind is, Dear God, I’m going to die this afternoon. The only question that remains is how long is it going to take Iowa to hit me? That’s a very compelling moment in your life. Life was good. And here I am forty-six years old and I’m going to die. My wife was my high school sweetheart, loved her dearly, and I had three beautiful children.” The last thing his wife had said to him was, “I love you, hurry home. I love you.” Fitch turned away from Dvorak’s gauges and saw that Records didn’t even have his shoulder harness fastened. Fitch leaned over him and fastened it.

Haynes had hoped that Fitch would know some secret trick to bring the plane back under control, perhaps a hidden button that only flight instructors get to know about that would make everything all right. Dvorak was telling United Airlines Systems Aircraft Maintenance in San Francisco, known as SAM, that they needed assistance and needed it quickly. When Fitch entered the cockpit and saw the hydraulic gauges reading zero, his reaction was similar to that of the United engineers at SAM, who were telling Dvorak that what he had reported was impossible. Having hydraulic fluid in the lines is a necessary condition of flight in a DC-10. After a complete loss of hydraulic power, the plane would have no steering. It would roll over and accelerate toward the earth, reaching speeds high enough to tear off the wings and tail before the fuselage plowed into the ground. Or it might enter into an uncontrollable flutter, falling like a leaf all the way to the earth, to pancake in and burst into flames. Under no circumstances would it continue to fly in any controllable fashion. To an expert pilot’s eye, what Fitch saw was like watching someone walk on water. Haynes later said that Fitch “took one look at the instrument panel and that was it, that was the end of his knowledge.”

Haynes told Fitch, “See what you can see back there, will ya?”

Records said, “Go back and look out [at] the wing and see what we’ve got.”

“Okay,” Fitch said, and he left the cockpit. As he hurried down the aisle, he brushed past Gerry and Joann Dobson in their Hawaiian clothes. He passed Brad Griffin in 2-E, who had been thrilled to make this trip to play in a golf tournament with his brother. Fitch passed Paul Burnham, whose body, at first unidentified, would be labeled with nothing more than the number 43. Fitch left first class and entered the coach cabin, standing by the exit door behind his own seat and Peter Allen’s. Allen would eventually escape from the wrecked aircraft by the seemingly impossible maneuver of going through a broken passenger window. In fact, he wasn’t the only one who attempted that. In the immediate aftermath of the crash, a young police officer named Pat McCann, who happened to be training at the airport that day, saw a man who had managed to get the upper half of his body through his window before the lower half was incinerated inside the plane.

Fitch passed down the aisle into B-Zone. What he saw through the window only deepened his dread. He crossed to the port side and looked out at the left wing to confirm what he suspected. He rushed back through A-Zone, passing row 9, where Upton Rehnberg, who wrote technical manuals for the aerospace giant Sundstrand, sat in the window seat. Helen Young Hayes, an investment analyst from Denver, sat next to Rehnberg, on the aisle. A young woman with Chinese features, Hayes was fashionably dressed in a miniskirt and blouse. Across the aisle from her sat John Transue, forty. Rehnberg and Hayes would soon share adjacent rooms in the burn unit at St. Luke’s Hospital. Transue would save Jan Brown’s life. Fitch reached the cockpit door and knocked. No one answered.

On the other side of the door, Haynes was saying, “We’re not gonna make the runway, fellas. We’re gonna have to ditch this son of a bitch and hope for the best.” Fitch knocked again, louder, and Haynes shouted, “Unlock that fuckin’ door!”

“Unlock it!” echoed Records.

Dvorak opened the door, and Fitch stepped into the cockpit. He’d been gone less than two minutes. He said, “Okay, both inboard ailerons are sticking up. That’s as far as I can tell. I don’t know.”

The extreme stress was still affecting Haynes’s thinking. He responded, “That’s because we’re steering—we’re turning maximum turn right now.” Ailerons always move in opposite directions, up on one wing and down on the other. Both of them can’t be up at the same time unless they’re floating from lack of hydraulic power.

“Tell me what you want,” Fitch said, “and I’ll help you.”

Haynes said, “Right throttle. Close one, put two up.” He was under so much stress that he had simply misspoken. In reality, he was trying to tell Fitch to reduce power on the left engine (one) and increase it on the right (three, not two, which had obviously quit). “What we need,” Haynes said, “is elevator control, and I don’t know how to get it.”

Fitch was confused but willing. “Okay, ah . . . ,” he said. He stood between the two pilots, took the handles in his hands, and began to move them in accordance with instructions from Haynes and Records, surfing this 185-ton whale five miles in the sky at 83 percent of the speed of sound.

Dudley Dvorak was known as an unflappable guy. He had started his career in the Air Force as a navigator and flew back seat in F-4 Phantoms in Vietnam. He had been a flight instructor and examiner in numerous aircraft during his military career. Dvorak retired from the Air Force in 1985 and joined United with two decades of experience. Haynes could not have asked for a more competent pilot. Despite that, as Dvorak talked to SAM in San Francisco, he was under so much stress that he was having trouble saying what he meant to say. “Roger, we need any help we can get from SAM as far as what to do with this, we don’t have anything, we don’t—what to do, we’re having a hard time controllin’ it, we’re descending, we’re down to seventeen thousand feet we have . . . ah, hardly any control whatsoever.”

In the meantime, Haynes suggested to Fitch that they try the autopilot, and Fitch said, “It won’t work.” Then Haynes began coaching Fitch concerning how to steer against the constant and uncommanded climbing and descending. “Start it down,” he said. Then, “No, no, no, no, no, not yet . . . wait a minute till it levels off . . . Now go!”

Immediately after the explosion, the plane made one big slow right turn about twenty to thirty miles in diameter. Then the plane proceeded to make several more spirals of five to ten miles each, downward and to the right. Robert Benzon, an investigator for the NTSB, would say later, “The flyers in the cockpit became instant test pilots when the center engine let loose. They were line pilots,” meaning workaday guys, “with no training on a total hydraulic failure situation. Period. They are heroes in every sense of the word.” In fact, the pilots who later attempted landings in a simulator that was configured to fly as the damaged DC-10 flew, found that the aircraft eventually crashed, despite their best efforts.

Haynes and Records continued to try to fly the plane using the yoke, even though the controls were dead. Haynes later said that after forty years of flying, it was difficult to get it into his head that he was flying a plane unless he was holding onto something. Fitch said the same thing: they reacted reflexively. And he later dared any aviator under those circumstances, “You let go of it if you’re the pilot.” Haynes also said that he and the crew really had no idea what had gone wrong with their beautiful ship.

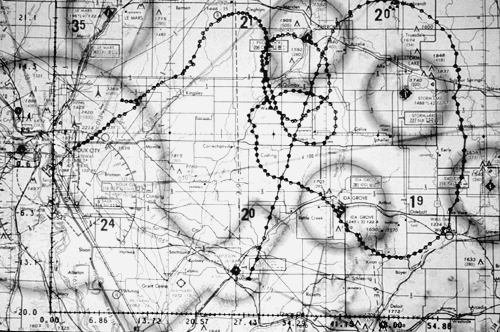

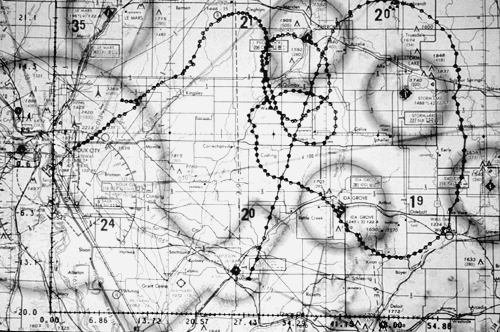

This radar track shows the path of Flight 232. The plane was traveling northeast at thirty-seven thousand feet. Just east of the Cherokee airport, the fan on the number two engine blew apart, cutting hydraulic lines and disabling flight controls. From NTSB Docket 437

As Fitch acquired a feel for steering with the throttles, Haynes asked, “How are they doing on the evacuation?”

“They’re putting things away,” Fitch said, “but they’re not in any big hurry.”

“Well, they better hurry,” said Haynes. “We’re going to have to ditch, I think.” Then, after a moment, “I don’t think we’re going to make the airport.”

Fitch’s response was, “Get this thing down, we’re in trouble!”

Many years later, Haynes laughed at that, saying that it seemed like a pretty profound case of stating the obvious. But as a TCA, Fitch knew that in the twenty-five years prior to this event, no one had ever survived the complete loss of flight controls in an airliner. They were merely buying time.

As Fitch nursed the throttles, Dvorak continued talking to SAM. Someone in San Francisco said, “We’ll get you expedited handling into Chicago. . . . Put you on the ground as soon as we can.”

Exasperated at the preposterous remark, Dvorak said, “Well, we can’t make Chicago. We’re gonna have to land somewhere out here, probably in a field.” Whoever was on the line at SAM was so shocked that the frequency went dead for more than a minute before anyone spoke again. And then all he had to say was, in effect, Tell us where you’re going to crash.

Even at this late stage, the gathered engineers on the ground at SAM were still scratching their heads in disbelief, and the cockpit was awash in confusion from the extreme stress that was making it difficult for the crew to think straight. Haynes denies that they were afraid, but from the mistakes they were making and the sound of their voices on the tapes, it is clear that this highly skilled crew with its long experience was not functioning normally. Fitch was later frank about how afraid he was. Records asked Haynes if he wanted to put out the flaps, but the flaps are hydraulically operated, so that was not possible. (Slats and flaps are extensions on the front and back of the wings, respectively. When deployed, they allow the plane to fly at slower speeds for takeoff and landing.) Haynes responded, “What the hell. Let’s do it. We can’t get any worse than we are and spin in.”

Records went so far as to pull the slat handle and report, “Slats are out.”

The wings aren’t visible from the cockpit, so the pilots were unable to see whether pulling that handle had any effect. But Fitch said, “No, you don’t have any slats.”

Haynes realized his mistake at last, saying, “We don’t have any hydraulics, so we’re not going to get anything.”

Moreover, at that point, they didn’t even know where they were. “Get on [frequency] number one,” Fitch said, “and ask them what the—where the hell we are.”

Haynes radioed the Sioux City tower, “Where’s the airport now, ah, for Two Thirty-Two as we’re turning around in circles?”

Bachman said, “United Two Thirty-Two Heavy, ah, say again.”

Haynes said, “Where’s the airport to us now as we come spinning down here?”

“United Two Thirty-Two, ah, Heavy, Sioux City airport’s about twelve o’clock and three-six miles.”

“Okay,” Haynes said, “we’re tryin’ to go straight, we’re not havin’ much luck.”

Indeed, in their uncontrollable series of right turns, they would drift farther away from the airport instead of closer to it. And yet that would put them at an altitude from which they might actually reach the runway.

Bruce Osenberg and his wife Ruth Anne were sitting in the center section of row 21 with their twenty-year-old daughter Dina between them. Tom Postle, forty-six, sat on Ruth Anne’s right. “We had just eaten our lunch,” Ruth Anne said more than twenty-three years later, “and I had just put a package of Oreo cookies from the lunch into my purse. And then we heard this loud explosion at the back of the plane.”

Dina, who had recently finished her sophomore year in college, turned to her father and said, “Daddy, I don’t want to die.”

“Dina,” he said, “we’re okay. Just be patient. Things’ll work out here.” He looked to his left to check the door over the wing. Beyond the bulkhead, Sylvia Tsao held her squirming toddler, Evan. Bruce decided that he was taking his family out that door as soon as they were on the ground. All three of the Osenbergs noticed that the plane had begun to perform a number of strange maneuvers. The first was its tendency to roll over on its back, which they noticed because they could see the earth out the starboard windows. That would not ordinarily be possible from their center seats. The plane had also begun a long series of excursions up and down. First the plane would descend, rapidly gaining speed. The increased speed would produce more lift on the wings, causing the plane to reverse direction and climb. As the plane climbed, it lost speed the way a ball does when it’s thrown in the air. As the speed bled off, the plane lost lift and resumed its descent. And so it went, with each oscillation taking a minute or so. The plane always wound up at a lower altitude. They were going to return to earth no matter what.

Bruce later said, “It felt like we were in a boat in rough waters rocking back and forth.” Sometimes the plane went into a bank as steep as 38 degrees. To the passengers the plane appeared to stand on its wingtip in knife-edge flight.

Immediately after the engine exploded, the man next to Ruth Anne, Tom Postle, brought out his old Bible. He had been reading it through much of the flight. Now as the Osenbergs talked among themselves, Postle glanced over and asked, “Are you praying people?” Ruth Anne said that indeed they were—they had been praying since the explosion. Now they all held hands and began to pray together.

In the cockpit, grunting with effort against the yoke, Haynes told his crew, “If we have to set this thing down in dirt, we set it in the dirt.” Haynes maintained his sense of humor throughout this grim interval. At one point he laughed and said, “We didn’t do this thing on my last [check ride].” Yet at the same time, the cockpit voice recorder picked up swearing, sighing, and groans of despair as the crew fought a losing battle.

As the plane approached Sioux City, Ruth Anne finished her last prayer with Postle and Bruce and Dina. She felt no fear. The praying had put her into a serene state of otherness. “I felt God’s presence,” she would say later, but she still had one concern that was gnawing at her in those moments before the great calamity of her life overtook her. “I had on a fairly new outfit that day, and in those days, very full skirts were in style.” In the middle of a hot July, she imagined that she could get away without wearing pantyhose. And wouldn’t you know it, she was about to be in a plane crash. “And my fear was that we were going to have to go down the chute and that my skirt was going to fly up, and whoever was on the ground to catch me was going to see that I didn’t have on pantyhose.”

Dvorak continued to plead with SAM. Haynes described this facility as “maintenance experts sitting in San Francisco for each type of [aircraft] that United flies. They have all the computers . . . all the history of the aircraft, all the other information that they can draw on to help a crew that has a problem.”

Fitch later said, “They know this airplane cold, they know all the systems, they have all the technical manuals, they have everything at their disposal, and if there’s a backdoor way of pulling a circuit breaker or something to do, they can see this backdoor way of helping you out.”

The first difficulty Dvorak encountered was that the engineers at SAM didn’t believe him when he said that the plane had no fluid in any of its three hydraulic systems.

“We blew number two engine and we’ve lost all hydraulics,” Dvorak said in his first transmission to SAM around 3:30 in the afternoon over Iowa, about eleven minutes after the engine exploded.

The engineer on the line at SAM said, “Your, ah, system one and system three? Are they operating normally?”

“Negative. All hydraulics are lost. All hydraulic systems are lost.”

“United Two Thirty-Two, is all hydraulic quantity gone?”

“Yes! All hydraulic quantity is gone!” Dvorak answered in frustration.

In his stuttering disbelief, the engineer at SAM asked, “Okay, United, ah, Two Thirty-Two, ah, what-what-what-what’s, ah, where you gonna set down?” In other words, Where can we find the wreckage?

Dvorak was practically begging by then, saying, “We need some assistance right now! We can’t, ah, we’re havin’ a hard time controllin’ it.”

When the engineer at SAM ran out of ideas, he said, “I’ll pull out your flight manual.” SAM had wasted two precious minutes getting to that point. The engineers at SAM thought that the crew had to be mistaken in its diagnosis. And in fact, later that evening, the chief training officer for the DC-10 at United in Denver, Mike Downs, would tell Roger O’Neil, a reporter for NBC television, that he had been listening in on the conversation between Dvorak and SAM. To begin with, Downs claimed that Dvorak never said that the plane had lost all hydraulics. (In fact, as Dvorak told me, “I repeat[ed] it over and over again to them.”) Downs further told O’Neil that he didn’t believe United 232 had suffered a complete hydraulic failure, because if it had, the plane would not have been able to fly at all.

But in the cockpit that afternoon, Dvorak opened his flight manual to compare notes with the engineer at SAM. Both men were realizing at about the same time that no procedure existed for what they were facing. In fact, during the investigation of the accident, a SAM engineer was heard to comment that they had no idea what to say to the crew, because they felt that they were talking to four dead men.

SAM replied to Dvorak, “United Two Thirty-Two, ah, in the flight manual, page 60 . . .” The engineer from SAM went to call other engineers, but no one had even a suggestion of what the crew might try.

“With all those computers, with all the knowledge at their fingertips . . . ,” Haynes said years later, “there’s absolutely nothing they could do to help a crew.”

Fitch later said that as he flew the plane with the throttles, he was wondering if “the aircraft was going to be a smoking hole in Iowa.”

Several minutes into the conversation with Dvorak, SAM was still asking him to confirm that he had lost all three hydraulic systems. Haynes was getting really angry, as Dvorak responded, “That is affirmative! We have lost all three hydraulic systems! We have no quantity and no pressure on any hydraulic system!”