MONDAY, JANUARY 22 | DAY 2

He walked along the long, red-carpeted corridor, striding past the portraits of former First Ladies and the Map Room, where Franklin D. Roosevelt had charted the course of World War II. A Secret Service man scampered in front of him, opening the twin sets of glass doors that led to the colonnade adjoining the Rose Garden. But instead of heading to the Oval Office, Nixon descended another flight of stairs to the West Wing basement. He strode across West Executive Avenue, the closed-off street that separated the West Wing of the White House from the monstrous neo-Baroque pile of the Executive Office Building. A grand outdoor staircase of twenty-six stone steps, framed by multiple pillars and balconies, brought Nixon to the hideaway office that he used for what he called his “brainwork.”

Nixon crosses West Executive Avenue from the West Wing to his private office in the Executive Office Building, or EOB.

Aerial view of the White House Mansion, the Rose Garden, the Oval Office, and the West Wing taken from the presidential helicopter as it landed on the South Lawn. The EOB, where Nixon had his hideaway, can be seen in the background.

For decades, the EOB had served as the unloved adjunct of the White House, a place of exile for bureaucrats who were not sufficiently close to the president to command an office in the West Wing. Dubbed “the ugliest building in America” by Mark Twain, it had been built in the aftermath of the Civil War to house a rapidly expanding federal bureaucracy. But it had acquired a sudden prestige as a result of Nixon’s decision to use the Oval Office primarily for ceremonial purposes. Obsessed with privacy and solitude, he was determined to escape the hothouse atmosphere of the West Wing and the prying eyes of aides and journalists who were still camped out in the lobby at the beginning of his presidency.

After reviewing various possibilities, he settled on an airy first-floor suite known as EOB 175, with twenty-foot-high ceilings and a patio overlooking the White House. He decorated his study with a selection of gavels from his time presiding over the Senate as vice president, dozens of miniature elephants, the symbol of the Republican Party, footballs, and a prized hole-in-one golf card. A collection of political cartoons celebrating his various election victories, beginning with his trouncing of the “soft on Communism” congressman Jerry Voorhis in California in 1946, adorned the walls of the staff office next door. Hidden behind the bathroom and kitchen, in the mysteriously named room 175½, was a telephone equipment closet used to house a battery of tape recorders connected to microphones drilled into the desk in Nixon’s office. The placement of the microphones made it difficult, sometimes impossible, to pick up conversations in other parts of the room.

Prior to moving in, Nixon had demanded that his study be equipped with “a big comfortable chair similar to the one I now have in the Lincoln Sitting Room.” His wife, Pat, arranged for a much-loved lounge chair and matching ottoman to be brought down from his Fifth Avenue apartment in New York, where he had worked as a lawyer before assuming the presidency. He also requested “a pretty good bookshelf” where he could place books by the authors he most revered, such as Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, and Charles de Gaulle. For relaxation, he turned to biographies of Theodore Roosevelt, political thrillers by writers like Allen Drury, and the World War II novels of Herman Wouk, which he kept on his desk.

Nixon permitted his alter ego, Colson, to move in to a neighboring suite but kept other top aides, including Haldeman, Kissinger, and his press secretary, Ron Ziegler, a safe distance away in the West Wing. They would come only when summoned.

A bodyguard logged the arrival of “Searchlight”—Nixon’s Secret Service code name—in the Executive Office Building at 7:56 a.m. on Monday, January 22. It was the first full working day of his second presidential term. As he stepped into his private office, he was greeted by his valet, Manolo. After ten years in Nixon’s service, Manolo had become accustomed to his routines. Breakfast usually consisted of cold wheat germ cereal, orange juice, coffee, and glass of skim milk, served in his bedroom. After breakfast, Nixon typically ran in place for a few minutes to get his adrenaline going. He had already picked out what he was going to wear the night before, a dark suit, white shirt, and sober tie. On this particular morning, he delayed washing up until arriving in his EOB suite. The voice-activated Sony TC-800B tape machine began rolling as he issued a gruff instruction to Manolo to fetch his bathrobe.

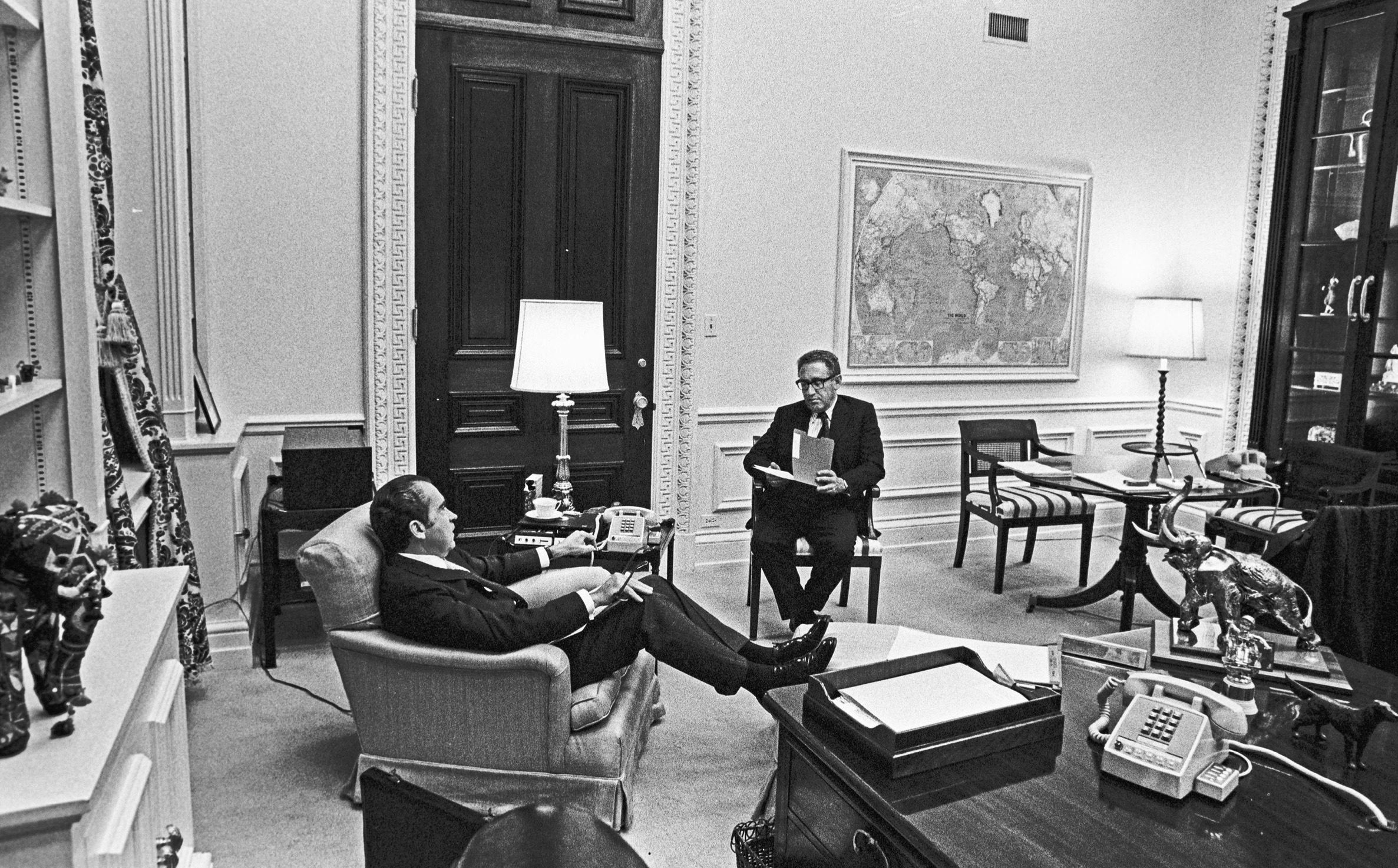

Kissinger poked his head around the heavy oak doors twenty minutes later. Nixon had been sitting in his armchair dictating a letter to the evangelist Billy Graham about the Sunday church service in the White House. He gestured to Kissinger to pull up a chair opposite him. “All set for your trip?” he asked. Kissinger assured him that the peace treaty would be initialed by Tuesday evening, in time for Nixon’s planned television broadcast. He had been shuttling back and forth between Washington and Paris for three and a half years. The first few meetings with the North Vietnamese had taken place in complete secrecy, surrounded by the kind of mystery and intrigue including disguises, false identities, and lies about his schedule that Kissinger relished. It was only after Nixon publicly revealed the existence of a back channel to Hanoi in January 1972 that reporters finally caught up with the man they came to call “Super K.”

Nixon with Kissinger in his hideaway office in the Executive Office Building. A paging device for summoning aides is visible beside the telephone on the president’s desk, at bottom right, alongside one of Nixon’s miniature elephants.

After Kissinger left the room, Nixon noticed with irritation that a key phrase was missing from the draft TV speech. He wanted to tell the American people that “peace with honor” had finally been achieved. But the speechwriters had omitted the phrase, perhaps because those same three words had been used by Neville Chamberlain to describe his ill-fated negotiations with Adolf Hitler at Munich, prior to World War II. Nixon, by contrast, associated the phrase with one of his political heroes, Woodrow Wilson, and the end of World War I. He reached Kissinger as he was being driven to Andrews Air Force Base in a White House limousine. The national security adviser assured him that the missing words would be restored. “It must be a typing thing.”

The president was still fuming over the protests that had been organized to coincide with his second inaugural, particularly a peace rally at the National Cathedral attended by members of the Kennedy family. He shared his contempt for the antiwar crowd in a telephone call with Kissinger’s former deputy, Alexander Haig, now back at the Pentagon as vice chief of staff of the army. Nixon relished the thought that his political enemies “must be gnashing their goddamn teeth” over the peace agreement.

“They will, of course, say that we didn’t get anything out of it,” said Nixon, referring to the criticism of the Christmas bombing campaign. “We didn’t get anything out of waiting since October, we could have gotten it then, it wasn’t worth fighting for four years, it isn’t going to last, it’s a bad peace, and so forth. I don’t think that’s going to wash with most people. Whaddya think?”

The newly promoted four-star general had recently emerged as the voice of the hard-liners on the National Security Council. He had opposed a framework peace deal negotiated by Kissinger back in October that would have ended the war on terms very similar to those embraced by Nixon three months later. He was happy to assure his commander in chief that he had been right to take a tough line with Hanoi.

“I don’t think it washes at all.”

“They were really a pitiful bunch during the inauguration, squealing around,” the president continued. “They are going to commit suicide, some of these bastards, you know. Really, physically, when they don’t have something to hate. Isn’t that it?”

“That’s exactly it.”

“They’re really so frustrated. They hate the country. They hate themselves. And that’s what it’s really about. It isn’t just war. It’s everything.”

The time had come for his daily meeting with his chief of staff, a stream of consciousness affair guaranteed to produce a stream of “action memos,” ranging from the vital to the trivial, that coursed through the many tributaries of the administration. Nixon reached out to a discreet white box, about the size of a cigarette pack, next to the telephone on his desk. Four push buttons were mounted on top. He pressed the first button, marked “H,” once, causing a loud bell to ring in Haldeman’s office down the corridor from the Oval Office. This was the signal for the former advertising executive to drop whatever he was doing and hurry into his master’s presence. There was no way of accidentally missing the bell, which was programmed to keep on ringing until either Haldeman or his secretary physically turned it off. The chief of staff appeared in EOB 175 a few minutes later.

With his closely cropped hair, lean physique, sober ties, and crisp white shirt, Harry Robbins “Bob” Haldeman looked like an advertisement for a management training school. Around the White House, he was known as “the Prussian”—a reference to his German ancestry but, even more significantly, to his reputation as a disciplinarian. “From now on, Haldeman is the Lord High Executioner,” Nixon had told his cabinet at the beginning of his presidency. “Don’t come whining to me when he tells you to do something. He will do it because I asked him to, and you are to carry it out.” Naturally averse to personal confrontation, Nixon had selected Haldeman as his instrument for dealing with the outside world. In addition to chopping off heads, his role was to serve as a shock absorber for the president’s temper tantrums and keep him focused on the job of running the country. He was at once his enforcer, his nanny, and his therapist.

They had been together for nearly two decades. After graduating from the University of California, Los Angeles, and doing a stint in the navy, Haldeman had risen through the ranks of the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency. His portfolio of clients ranged from Walt Disney to the toilet bowl cleaner Sani-Flush. He worked as an advance man for Nixon during his vice presidential campaign in 1956. For the 1960 presidential campaign that pitted Nixon against Jack Kennedy, Haldeman was promoted to campaign tour manager. For an entire year, the two men were virtually inseparable, a process repeated two years later, when Nixon ran unsuccessfully for governor of California. Nixon spent more time with Haldeman than anyone else. They complemented each other’s strengths and weaknesses. The visionary Nixon was incapable of running a campaign or large organization; Haldeman was the quintessential marketing man with no political ambitions of his own. Together, they merged into a formidable leader. In the opinion of John Ehrlichman, another UCLA alum brought into the White House by Haldeman, it was “hard to tell where Richard Nixon left off and H. R. Haldeman began.” Sometimes, when Nixon wanted to disguise his authorship of a reprimand, he would simply issue it in Haldeman’s name. As Haldeman put it, “Every president needs an S.O.B.—and I’m Nixon’s.”

Entrusted with building a White House staff after Nixon won the presidency in 1968, Haldeman sought out carbon copies of himself. Many of the people he recruited were university friends like Ehrlichman, who was put in charge of domestic policy, or associates from the advertising world like Ron Ziegler, who became press secretary. They were all clean-cut young men, conservative in outlook but more focused on execution than ideology. Many had gone through the election campaign ordeal as Haldeman-trained advance men. They were expected to be “nameless and faceless, as unobtrusive as possible, always concerned for the candidate, never thinking of their own comfort.” Their job was to ensure that cars were parked in the right sequence for motorcades, camera angles perfectly aligned, microphones properly positioned, and high school bands appropriately thanked. They were permitted to share a joke at the end of a long day, as long as they preserved a united front to the outside world. Haldeman had various sarcastic nicknames for the president, including Leader of the Free World, Milhous (Nixon’s middle name), and Thelma’s Husband, after Pat Nixon’s discarded first name. Ehrlichman referred to Nixon as the Mad Monk. But these were all inside jokes, never to be shared with others. Loyalty and cool efficiency were the qualities Haldeman prized most.

Haldeman’s greatest strength in managing the frequently irascible Nixon was inexhaustible patience. He had the ability to sit with his boss for hours, listening to his monologues and diatribes. He was always available, responding to the president’s telephone calls in the middle of the night without betraying a hint of irritation. There was often little ostensible purpose to these conversations. Haldeman understood that the president simply needed to ruminate, particularly when faced with a big decision. Haldeman called this process “circling like the dog.” Just as a dog paces round and round when he is trying to settle down, so too Nixon would go off on obscure tangents before eventually deciding on a course of action. It was Haldeman’s job to gently hold the leash, to allow Nixon to be Nixon without inflicting too much damage on either the country or himself. On occasion, this meant ignoring Nixon’s instructions, or at least delaying implementation, until the president had moved on to some other obsession.

Haldeman’s approach differed markedly from that of Chuck Colson, who believed that Nixon’s orders should be carried out without hesitation. This was part of Colson’s appeal to Nixon. “Colson—he’ll do anything,” Nixon liked to brag. “He’ll walk right through doors.” Colson’s willingness to fulfill Nixon’s every wish extended to trivial matters like organizing an impromptu expedition to the Kennedy Center to attend the final moments of a military concert. “You could have put the president’s life in jeopardy,” Haldeman shouted, when he heard about the unauthorized addition to Nixon’s schedule. “Just tell him he can’t go, that’s all. He rattles his cage all the time. You can’t let him out.”

After many years of observing Nixon, Haldeman had concluded that his boss was “the strangest man I ever met.” To take a minor example, Nixon was obsessed with organizing his time efficiently. He boasted about his ability to “add hours to the day by not sleeping.” He once calculated that he could save a few seconds by shortening his official signature from “Richard M. Nixon” to plain “Richard Nixon.” Whenever possible, he would simply write “RN.” In compliance with this theory, senior staff members were all identified by single initials. Haldeman became “H,” Ehrlichman “E,” Kissinger “K.” All these time-saving devices were offset by Nixon’s passion for minutiae. The president spent many hours discussing which pictures would hang where in the West Wing, how he should be greeted on entering a room, when his dog would be given a bath, and so on. Haldeman became accustomed to receiving bizarre directives like “no more soup at dinners” (after Nixon spilled soup down his shirt at a state dinner) and even “no more landing at airports” (after an airport arrival ceremony went awry).

While Haldeman was more aware than anyone of Nixon’s idiosyncrasies, he considered him “head and shoulders” above “the run of ordinary mortals.” A remarkable memory enabled Nixon to dredge up arcane details of events and slights that everyone else had forgotten. This was combined with a facility for absorbing new information extremely quickly. The only person in Haldeman’s experience comparable to Nixon in personal drive and scope of imagination was Walt Disney. Both men were plagued by “incredible self-doubt” and burned up people around them, but both were “exceptional” in their own way. Both were tough on their subordinates. During their entire sixteen years together, Nixon had never treated Haldeman as a friend, only as an employee. There had been only one family dinner together with their wives, back in 1962. Haldeman spent so much time with Nixon that he had almost become a stranger to his own family. Sitting down next to the president, his hand hovered over his own legal pad, ready for instructions.

The first order of the day was for a misleading “leak” to The Washington Post and Dan Rather of CBS. Nixon’s number one enemies in the press should be informed that the Vietnam peace settlement would be initialed in Paris on Friday rather than Tuesday as already agreed with Kissinger. The purpose was simple: Throw “the bastards” off balance.

Next, Nixon began obsessing over minor hitches in the inaugural ceremonies. At one event, he had been annoyed to see a member of the presidential press pool stationed between him and the TV cameras. “In next four years, never again have press in front of P,” Haldeman recorded dutifully, underlining the word “never.” Switching topics, Nixon instructed his chief of staff to find “an impresario” for White House entertainment, which should include “more country music.” He then began fretting over the public perception that he was somehow isolated from criticism. He told Haldeman to get the word out that he read three national newspapers a day, in addition to scanning the regional coverage. Shifting back to the inaugural events, he wanted to ensure that the antiwar protester who ran toward the presidential limousine on Pennsylvania Avenue was properly charged. He could be released later—as a well-publicized act of presidential clemency. Changing gears yet again, he announced that “a humor man” should be added to his speech-writing staff, as part of his efforts to lighten up.

After more than two hours of these and similar ruminations, Nixon allowed Haldeman to escape. He called for Manolo and requested a bowl of consommé. Normally, his lunch consisted of cottage cheese and a slice of pineapple, but he had eaten much more than usual at the inaugural lunches and dinners. He was proud of keeping his weight down to 173 pounds, precisely what it had been at the age of forty, twenty years earlier. He made “a fetish” out of self-discipline. “It’s important to live like a Spartan,” he told a journalist. “The worst thing you can do in this job is to relax, to let up.” After wolfing down the clear broth, he withdrew into his “thinking time.”

From Nixon’s point of view, the two and a half hours after lunch were the most essential of the day. His aides knew he was to be left undisturbed during this downtime. Sometimes, he would relax on his lounge chair, reading a history book or biography of one of his political heroes while scribbling notes on a yellow pad. Sometimes, he would listen to booming classical music from the tape deck behind him. And sometimes, he would stretch out on the long settee opposite his desk and nod off to sleep. He claimed he was following the example of LBJ, who recommended a snooze in the middle of the day as a means of cramming two workdays into one. But the truth was that Nixon needed to nap during the day because he slept so irregularly at night. His sleep patterns had been mixed up for years, and he rarely got enough rest.

Nixon cherished his moments of solitude. He drew strength from the years he had spent in the wilderness between his defeat by Jack Kennedy in 1960 and his election as president in 1968. He tried to model himself on General de Gaulle, who retreated to his home in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises after stepping down as head of France’s provisional government in 1946. In his well-thumbed copy of de Gaulle’s memoir The Edge of the Sword, Nixon underlined the sentence “Great men of action…have without exception possessed in a very high degree the faculty of withdrawing into themselves.”

One of the principal lessons that Nixon drew from de Gaulle was the importance of creating a mystique around his office. “Thinking about schedule, he feels that he should be more aloof, inaccessible, mysterious,” Haldeman recorded at one of their daily meetings, early in his presidency, pointing to de Gaulle as an example. “Read de Gaulle on the mystery of power, the power of mystery,” Nixon told his aides on another occasion. “He understood that better than anybody.” As instructed, they looked up the relevant passage in The Edge of the Sword. “There can be no power without mystery. There must be a ‘something’ which others cannot altogether fathom, which puzzles them, stirs them, and rivets their attention…Nothing more enhances authority than silence.”

Nixon’s problem was that he was almost entirely lacking in the personal charisma that distinguished wartime leaders like de Gaulle and Churchill or even some of his own contemporaries, such as Jack Kennedy. He both envied and resented JFK for his seemingly effortless grace and hold over the popular imagination. By contrast, nothing came easily to the poor boy from Yorba Linda, California, who had clawed his way to the top of the political pile through sheer determination. At Duke University, he had been given the nicknames Gloomy Gus and Iron Butt for the countless hours he spent holed up in the law library while other students were out enjoying themselves. It was the same with politics. With Nixon, everything had to be studied and practiced. Dealing with other people was particularly painful. As he once observed, he was “an introvert in an extrovert profession.”

An avid reader of history books and biographies, Nixon had been a student of greatness all his adult life. At moments of crisis, he would compare his woes with those of former presidents. At the height of the Vietnam War, when the White House was circled by heavy trucks to hold back demonstrators, he comforted himself with the thought that Abraham Lincoln had endured much worse. He reminded his aides that Lincoln had to deal with an insane wife who lost two of her brothers fighting for the Confederacy, a rebellious cabinet, and a secretary of war who refused to speak to him. At one point, Nixon recalled, Lincoln ordered cannons to be lined up on the streets of New York to shoot draft resisters. “All of those things added up make our situation look pretty simple,” he concluded.

Many of Nixon’s historical analogies dealt with rejection and redemption. He saw himself as an outsider engaged in an endless war with a political establishment determined to destroy him. The leaders he most admired were those who had followed a similar trajectory. He quoted with approval the opinion of his friend the former Texas governor John Connally that “Lincoln was the great figure of the 19th century and Churchill and de Gaulle were the two great figures of the 20th century. The big thing about all of them is their comeback from defeat, not their conduct of the wars.” Aides noted that Nixon was most impressive when he was up against a wall fighting for his survival, looking for creative ways out of seemingly impossible situations. Victory had the curious effect of depriving him of his energy and drive.

By his own account, he had gained little personal satisfaction from his landslide defeat of George McGovern in the 1972 election. He had won every state in the Union, with the exception of Massachusetts, capturing more than 60 percent of the popular vote. He had the support of every key population group identified by the exit polls with the exception of blacks and Democrats. Some of these groups, such as Catholics and members of labor unions, had never before been in the Republican column. He had achieved his goal of building a “New Majority,” but felt curiously deflated now that he had secured his victory. He was a passive bystander to the excited celebrations taking place around him. He would long remain “at a loss to explain the melancholy that settled over me on that victorious night.”

The following day, he assigned Haldeman the task of demanding the resignations of every single member of his staff. He planned to get rid of many of them, keeping only those who had proven their energy and loyalty. He had just finished reading a biography of Benjamin Disraeli, the Victorian-era British prime minister. While serving as leader of the opposition, Disraeli had talked dismissively about the “exhausted volcanos” sitting opposite him on the government benches in the House of Commons. For Nixon, Disraeli’s phrase summed up the perils faced by politicians who had been in office too long and run out of new ideas. “We must avoid the exhausted volcano syndrome,” he told his aides. “We must recharge ourselves.”

He worried incessantly about how he would be perceived in the pantheon of American presidents. On a flight back to Washington from his Florida home at Key Biscayne just prior to the election, he scribbled a private note to himself that he squirreled away in a drawer of his desk in EOB 175:

Presidents noted for:

FDR-Charm.

Truman-Gutsy.

Ike-Smile, prestige.

Kennedy-Charm.

LBJ-Vitality.

RN-?

As he began his second term as president, Nixon wanted above all to be remembered as a peacemaker. He dreamed of the “big plays,” like the opening to Communist China or détente with the Soviets or ending the Vietnam War. “Being president is nothing compared to what you can do as president,” he told his aides. Like Teddy Roosevelt, he yearned to be “the man in the arena.” He believed that his best days were yet to come. On his sixtieth birthday, January 9, 1973, he made a list of “older men” who achieved their greatest victories late in life. The list included de Gaulle, Eisenhower, Churchill, Adenauer, and Chou En-lai. “No one is finished until he quits,” Nixon jotted down on his legal pad. “Age—not as much time. Don’t spin your wheels. Blessed with good health. Live every day as if last.” He might be running out of time, but he was still younger than all the political giants on his list at the height of their political power. He still had another four years to change the world.

Nixon emerged from his thinking time in a foul mood. Among the materials stacked neatly on his writing table was the latest edition of Time magazine. It included an interview with a former CIA official named Howard Hunt who had run undercover operations against Nixon’s political enemies. Hunt had been dragged into the Watergate scandal when his EOB telephone number and easily deciphered initials had been found in the address book of one of the burglars the day after the break-in. Along with his Cuban subordinates, he had recently pleaded guilty to conspiracy, burglary, and eavesdropping in federal court in Washington. The interview contained dark hints that Hunt was prepared to reveal who ordered the bugging of Democratic Party headquarters unless he and his friends were properly looked after. Hunt had already received nearly $200,000 from his “friends” in the administration, supposedly to cover his defense costs. The secret cash payments had come out of unused campaign funds and been delivered through intermediaries. It now seemed Hunt wanted more money. He was also, not very subtly, pushing for a presidential pardon.

“I protect the people I deal with,” Hunt told the Time magazine reporter, referring to his long career with the CIA, which included planning the failed Bay of Pigs operation against Fidel Castro in 1961. “A team out on an unorthodox mission expects resupply, it expects concern and attention. The team should never get the feeling that they’re abandoned. End of story.”

Most damaging to Nixon was an unsourced claim in the article implicating two of his closest associates in the bungled bugging operation. One of the men named by Time was Colson, who knew Hunt through the alumni network of Brown University and had hired him to work at the White House. The other was Nixon’s old law partner John Mitchell, who had served as attorney general and later as head of the Committee to Re-elect the President. The official abbreviation was CRP, but it was more popularly known as CREEP. “It’s got to be done,” Hunt had allegedly told the burglars as they were preparing to break in to the Watergate complex. “My friend Colson wants it. Mitchell wants it.” If either Colson or Mitchell could be shown to be involved, the scandal would move a big step closer to the president himself.

The Time story enraged Nixon. Even today, there is no credible evidence that he ordered the Watergate break-in, or knew about it in advance. Most people who investigated the matter, including many of Nixon’s otherwise harsh critics, concluded that he had no prior knowledge. On the other hand, there is little doubt that he set in motion the chain of events that resulted in the bugging of Democratic Party headquarters by waging an all-out war against his political enemies. His own tapes would demonstrate that he led the conspiracy to obstruct the FBI’s investigation into the crime, assisted by Colson, Mitchell, Haldeman, and others. His relationship with Colson, his surrogate son and alter ego, was particularly complicated. Many years later, Colson acknowledged that he helped to bring out “the dark side of Nixon,” but “it was always close to the surface. He was a gut fighter…His first reaction was to fight back.”

Time had been very friendly to Nixon during his political ascent, putting him on the cover numerous times and praising his anti-Communist rhetoric. The magazine was generally regarded as a conservative publication, with its finger on the pulse of mainstream America. But the once symbiotic, mutually beneficial relationship between ambitious politician and influential media outlet had frayed to breaking point in recent years. Sensitive to even mildly critical coverage, Nixon had rejected attempts by Time editors and reporters to gain favorable access. He now regarded the magazine as part of the liberal media conspiracy against him. It could no longer be relied upon for sympathetic, or even objective, reporting. Next to The Washington Post, Time had been most aggressive in covering the Watergate story. They had particularly good sources in the FBI.

Nixon discussed the Time story with Colson, whom he had summoned from the office next door. Colson denied any prior knowledge of the Watergate bugging and threatened to sue the magazine for libel: he claimed that the article had been written with “malice aforethought.” With Colson sitting beside him, Nixon then called Press Secretary Ron Ziegler. Speaking in clipped, angry tones, he was barely able to contain his rage.

“In view of Time using that story on Mitchell and Colson, anybody, anybody in the White House who talks to anybody from Time, his resignation must be on my desk within one minute. Is that clear?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You get that order around as fast as you can. You tell the NSC crowd: no calls at all are to be taken or returned from Time magazine unless I approve them in the future. Is that clear?”

“Yes, sir.”

Slamming down the phone, Nixon called back one minute later to say that his order applied to the entire foreign policy bureaucracy as well as the economic affairs apparatus, supervised by John Ehrlichman.

“Of course, it’s particularly important to get this to the NSC crowd. And I want you to call Haig and tell him I expect him to enforce it at the Pentagon.”

“Okay.”

“You are to hit Ehrlichman hard on it. He is to take that whole goddamn domestic council—all the left-wingers in there—and shut their damn mouths.”

“Yes, sir.”

Nixon had barely finished dealing with the fallout from the Time article when he began picking up rumors that President Johnson might be dead. He had been looking forward to sharing news of a Vietnam peace settlement with the president who had been hounded from office by the antiwar movement. Although they represented different political philosophies—Nixon was determined to wind down the Great Society welfare programs launched by Johnson—he felt a kinship with his predecessor over Vietnam. He recalled with horror the “awful, mindless chant” of the antiwar protesters, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” Johnson’s mistake, in Nixon’s view, was to attempt to buy off his youthful critics. The “hatefulness” of their attacks on Johnson’s Vietnam policy, Nixon wrote later, “frustrated him, then it disillusioned him, and finally it destroyed him.”

It took several calls from Haldeman to establish that Johnson had suffered a fatal heart attack at his ranch in central Texas. He had died in an ambulance plane on his way to a hospital in San Antonio. Nixon’s main concern, on hearing of Johnson’s death, was to head off any attempt to organize a memorial service for LBJ at the National Cathedral. In Nixon’s mind, the cathedral and its dean, Francis Sayre, were synonymous with the antiwar crowd. The fact that Sayre was a grandson of a former president—Woodrow Wilson—and had even been born in the White House himself merely added insult to injury. Nixon regarded the dean as a sanctimonious “ass.” Prior to staging an antiwar rally to coincide with the inaugural, Sayre had personally led a “peace march” to the White House to denounce the Christmas bombing of North Vietnam. When Harry Truman died a few days later, Nixon had refused to attend a commemorative service at the Gothic-style cathedral, high on a hill overlooking Washington. He preferred to sulk by himself three miles away at the White House rather than sit through one of Sayre’s moralizing sermons.

“Regardless of what all these babbling idiots say,” he lectured Haldeman, referring to members of his own staff who were urging him to be “presidential,” “there is not to be anything at that cathedral. I will not go, even if it’s the only thing. Is that clear?”

Haldeman assured him the Johnson family was unlikely to select the cathedral as the site of a memorial service, but Nixon would not drop the subject.

“I just hope that—Christ, Bob, on this one—the Johnsons will be savvy enough not to let that goddamn cathedral get into it…If Ziegler or one of our other little boys get a question about this, they’re to stand damn firm. ‘The president will not go to the cathedral.’ I want that said. You understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

Nixon’s voice rose to a shout. “Draw the line, goddamn it!”

“Draw the line,” Haldeman echoed dutifully. “The son of a bitch runs the place.”

“I’m not going to the cathedral. That’s all there is to it. I mean, he’s in the pale as far as I’m concerned.”

“He’s opposed to the national policy.”

“That’s right. He’s opposed to Johnson; he’s opposed to me. To hell with him!”

The president had been planning a television address attacking Johnson’s welfare programs and calling on Americans to learn the virtues of self-reliance. It occurred to him that this was hardly in “goddamn good taste,” given the circumstances. He did not want to “kick the hell out of the Great Society” only hours after paying tribute to its creator. Instead, he mused, the mourning period for Johnson might be an opportunity for him to escape to Florida for some rest.

With his appreciation for history, and particularly his own place in it, Nixon quickly picked up on a piece of presidential trivia his aides had missed. “This is the first time in forty years there hasn’t been a former president,” he told Colson later that night. The deaths, in rapid succession, of Eisenhower, Truman, and now Johnson meant that Nixon was the only living person who had served as leader of the free world.

Colson, as always, was suitably impressed. “My God, I hadn’t thought of that.”