QUARTERMASTER DEPARTMENT. In 1845, the Quartermaster Department—led since 1818 by quartermaster general, Maj. Gen. Thomas Sidney Jesup (q.v.)—was ill prepared for war. Congress had cut military manpower after the Seminole War as well as funds needed to maintain readiness. Wagons were scarce, wagon parts were not interchangeable, and experienced teamsters were hard to find; animals to pull wagons were in short supply; sufficient drivers were unavailable. Both oceangoing ships and shallow-draft boats for transport of troops and supplies were lacking. Clothing and equipment—the responsibility of the Quartermaster Department since the abolishment of both the Clothing Bureau in 1841 and the Office of the Commissary General of Purchases in 1842—were barely sufficient for a peacetime army manning frontier posts.

At the beginning of the war with Mexico, the Quartermaster Department had a staff of 31 of its 37 authorized officers. Throughout the war, the department had no quartermaster units. This meant that quartermaster officers only supervised logistics planning and execution—actual work (as with the engineers [q.v.]) had to be accomplished by line troops. What the department lacked in quantity, however, it made up for in quality, experience, and resourcefulness. Lt. Col. Thomas F. Hunt (q.v.) and Col. Trueman Cross (q.v.) had entered active service shortly after Jesup was made quartermaster general; they and Col. Henry Stanton had frequently developed their decision-making and leadership skills as acting quartermaster general when Jesup had to be away from Washington. Although Congress authorized regimental quartermasters to be appointed within volunteer units in the summer of 1846, the Quartermaster Department did not begin to increase in size until 10 months after the outbreak of war.

Before the conflict—from June 1845 when the War Department (q.v.) ordered Gen. Zachary Taylor (q.v.) to move from Fort Jesup (q.v.) to Texas (q.v.) and May 1846 when the war started—Jesup made an inspection tour of the army, leaving Colonel Stanton in charge. Key posts were filled by respected officers: Lieutenant Colonel Hunt went to New Orleans; Maj. Osborn Cross (q.v.) (son of Col. Trueman Cross) was assigned to Fort Jesup, Capt. George W. Crossman was sent to Taylor’s headquarters, and Col. Trueman Cross was sent to the southwest in charge of Hunt and six other quartermaster officers assigned to Texas.

James K. Polk (c. 1849). Daguerreotype. Courtesy Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Zachary Taylor and His Staff at Walnut Springs (1847). William Garl Brown, Jr.; oil on canvas. NPG. 71.57. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Taylor third from left; William W. S. Bliss, fourth from left; Braxton Bragg, standing, sixth from left.

Zachary Taylor (1848). Sarony and Major lithography company, NPG. 85.163. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Mariano Arista. The Benson Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

Pedro de Ampudia (c. 1847). The Benson Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

William Jenkins Worth (1844). Lithograph by Charles Fenderich. Edward D. Weber Lithography Company, 1844. NPG 66.99. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

John Ellis Wool (c. 1862). Photograph by Charles DeForest Fredricks, NPG. 80.329. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

John Macrae Washington (c. 1847). Daguerreotype. Courtesy Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Jefferson Davis. (1849). George Lethbridge Saunders, watercolor on ivory. NPG. 79.228. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Stephen Watts Kearny (c. 1847). Carruth & Carruth, Printers, Oakland, California. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Alexander W. Doniphan (c. 1850). Portrait from William Elsey Connelley, Doniphan’s Expedition and the Conquest of New Mexico and California (Kansas City: Bryant & Douglas, 1907).

David E. Conner. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Matthew Calbraith Perry (c. 1855). Unidentified photographer. Daguerreotype. NPG 77.206. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Franklin Pierce (c. 1848). Benjamin W. Thayer Lithography company. NPG. 77.275. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Robert E. Lee (c. 1861). Charles G. Crehen, after photograph by Mathew Brady. NPG 84.83. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Ulysses S. Grant (c. 1848). From U. S. Grant, Personal Memories of U.S. Grant, Vol. I (New York: Webster, 1885).

Thomas J. Jackson (c. 1863). Dominique C. Fabronius, after unidentified artist. Louis Prang Lithography company. NPG. 76.45. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

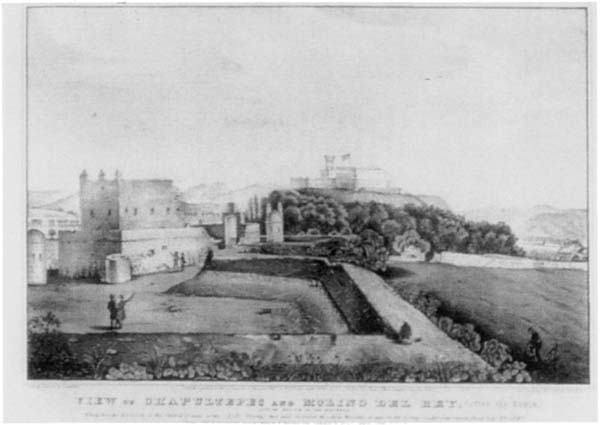

View of Chapultepec and Molino del Rey. Lithograph by N. Currier. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

At the outset of the war, the Quartermaster Department was stretched to supply Taylor’s army. The 300-plus wagon train in Taylor’s army during its march to the Rio Grande (q.v.) was composed largely of scavenged wagons and animals. As the war progressed, however, the situation was alleviated to a great extent as additional wartime funds were allocated by Congress and as the department settled into the rhythm of supplying a war different than those that the United States had fought before. The number of quartermaster officers increased; wagons were built, wagon trains were staffed, and animals were procured; ships were built or acquired to facilitate the flow of men and supplies; packaging was waterproofed and slimmed down in size to better meet the hardships of long supply lines; goods were manufactured; the supply process was improved for the duration of the war by allowing the department to make purchases on the open market instead of by the slow and less flexible process of bidding; and market prices settled back down somewhat from their surge due to the military’s sudden need for transport and equipment at the war’s outset.

The department’s job was complicated by numerous factors. Most important among them were that (1) the volunteer force increased at a fast and uneven rate, which made it difficult to know what supplies, equipment and transport would be needed; (2) in the northern Mexico campaign in 1846, Taylor, unlike Winfield Scott in the southern campaign the following year, was slow to requisition wagons and steamboats; (3) the War Department was unaccustomed to procuring the type of shallow-draft steamboats needed, and it was difficult to get these weakly powered boats to their destinations; (4) the army, accustomed to cumbersome comforts, bulky rations, and the convenience of wagons, was reluctant to travel light, a necessity in the mobile warfare demanded in the Mexican campaigns; (5) topographical surveys had not been made of the Rio Grande or many harbors and bays, which made it difficult to provide for water transport; (6) the Quartermaster Department had the responsibility of supplying multiple, geographically separated armies over the long, insecure supply lines of the armies of Generals Zachary Taylor, John E. Wool (q.v.), Stephen Watts Kearny (q.v.), and Winfield Scott; and (7) sorely needed funds were always slow to be authorized and slow to arrive in the coffers of the Quartermaster Department.

The heightened wartime responsibility of the Quartermaster Department did not end with the close of hostilities. The logistics process had to be reversed as the nation returned to peace—troops had to be returned to the United States, animals had to be disposed of, ships had to be sold, and surplus property in Mexico had to be auctioned or returned to the United States.

The great captains of the war—Taylor, Scott, and many of their fellow senior officers—frequently criticized the lack of timely logistics support during the war in their letters and reports. But the tasks were great, and the Quartermaster Department performed admirable service under circumstances unique in America’s military history.

QUERETARO, QUERETARO. After Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna (q.v.) abandoned Mexico City (q.v.) in September 1847, half of his forces went with him to carry out the siege of Puebla (q.v.), and half were sent 150 miles north to Querétaro under the command of ex-president and general José Joaquín de Herrera (q.v.). The following month, Querétaro became the temporary capital of Mexico as the United States continued its occupation of Mexico City. After both nations ratified the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (q.v.), a U.S. force under the command of Pres. James Knox Polk’s (q.v.) brother, Maj. William H. Polk (q.v.), traveled to Querétaro in late May 1848 to exchange ratification documents with the Mexican government.

QUIJANO, BENITO (1800–1865). During the lull after the battles of Contreras and Churubusco (q.v.), Brig. Gen. Benito Quijano served as a commissioner for Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna (q.v.) in negotiations to arrange a cease-fire. The agreement proved temporary, and fighting soon resumed. In February, after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (q.v.) had been signed, Quijano again sat for the Mexicans in negotiations that arranged a final armistice between his country and the United States.

QUITMAN, JOHN ANTHONY (1798–1858). The son of a Lutheran pastor in New York who wanted his son to also enter the ministry, John Anthony Quitman was well educated by private tutors. Instead of following in his father’s footsteps, however, he taught English at a Pennsylvania college before studying law and being admitted to the bar in Ohio. He later moved to Natchez, Mississippi, where he became a prominent politician. He served in the Mississippi legislature and was briefly acting governor of Mississippi. Quitman raised a company of volunteers (q.v.) called the Fencibles and took them to Texas in 1836, although they missed seeing action in the Texas revolution.

In the war with Mexico, Quitman was one of the six brigadier generals of volunteers appointed from civilian life as a result of congressional authorizations in May 1846. Quitman and his volunteer troops joined Taylor’s army and participated in the battle of Monterrey (q.v.) before moving south in December 1846 to join Gen. Winfield Scott’s (q.v.) gathering army. Quitman took part in the siege of Veracruz (q.v.) and commanded a brigade through the battle of Cerro Gordo (q.v.) and a division after his promotion to major general in the late spring of 1847. He led his division in the battles for Mexico City (q.v.) in August and September 1847. Quitman’s division spearheaded the attack on Chapultepec (q.v.) on September 13. Later that day, leading a composite force gathered from the Chapultepec assault, he was the first to reach the defenses guarding the center of the city. In fierce combat to take the Belén Gate (q.v.) and repulse counterattacks from the citadel (q.v.), Quitman’s force suffered high casualties, among those most of his staff and artillery officers. At daybreak on September 14, 1847, the battle for Mexico City ended when Quitman led his division into the central plaza after Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna’s (q.v.) army withdrew. For two months, Quitman served as the first military governor of Mexico City before returning to the United States. Although criticized by some as vain and obsessed with personal glory, Quitman was considered by most observers to be one of the more professional and effective of the volunteer generals in the war.

After the war with Mexico, he became governor of Mississippi. While in office, Quitman was charged with violating U.S. neutrality laws with regard to a filibustering expedition to liberate Cuba. Although he was never convicted of the charge, he resigned the governorship. Quitman was elected to two terms in the U.S. Congress before dying while in office on July 17, 1858.