All of the Generals are very much aware that if we have sufficient evidence on Contreras, there is no way that he would have done it without informing Pinochet, with whom he had breakfast every single day.

—Top-Secret White House memorandum, June 1978

Plan to Disrupt Chile’s Plebiscite: We take seriously intelligence reports that Chilean Army elements, using violence as a pretext, may try to suspend Wednesday’s scheduled plebiscite if Pinochet appears to be losing.

—Presidential Evening Reading for Ronald Reagan, October 1988

The Letelier-Moffitt assassination would dominate U.S.-Chilean relations for more than a decade. Along with the end of the Nixon-Ford-Kissinger era and the election of a “human rights president,” Jimmy Carter, the car bombing initiated a long transformation in U.S. policy toward the Pinochet regime. Carter, who blasted the Ford administration for overthrowing “an elected government and helping to establish a military dictatorship” during the campaign, gave new prominence to human rights as a criterion in U.S. foreign policy, but failed to hold the regime accountable for its atrocities in Washington. The Reagan administration attempted to reestablish cozy relations with the military government, only to find U.S. policy trapped by the reality of Pinochet’s act of terrorism on U.S. soil and increasingly threatened by Pinochet’s efforts to perpetuate his power. During the decade between 1978, when Chilean officials were officially indicted for the assassination, and 1988, when the military regime was peacefully voted out, Washington’s posture slowly evolved into an unequivocal rejection of the still violent and bloody Chilean military dictatorship.

For more than a year it appeared the Pinochet regime had actually gotten away with the most flagrant terrorist act committed in Washington in the twentieth century. Within days of the assassinations, CIA informants pointed the finger at Pinochet, and the FBI identified DINA and Operation Condor as lead suspects. Yet in September 1977 the Carter Administration actually invited General Pinochet to Washington to join other Latin American leaders at the signing of the Panama Canal treaty. During a prestigious face-to-face meeting at the White House, President Carter avoided any mention of the Letelier-Moffitt case and only mildly pressed his guest on human rights issues. According to the memorandum of conversation, “President Carter/President Pinochet Bilateral,” Carter stated that he did “not want anything to stand in the way of traditional U.S.-Chilean friendship.” Pinochet returned to Santiago “relieved and pleased by the entire Washington experience,” deputy chief of mission Thomas Boyatt reported. “The presidential bilateral has provided Pinochet with a hefty shot in the arm. . . .”

It took U.S. authorities almost seventeen months to bring the Letelier-Moffitt investigation into Chilean territory. Cooperation from the CIA, the agency with the most evidence of Chile’s international terrorist operations in its files, was ambivalent at best. In October 1976, the White House requested the CIA director George H. W. Bush to undertake “appropriate foreign intelligence and counterintelligence information collection” to support the criminal investigation. But the Agency did not provide Justice Department investigators with particularly useful information and details on the CIA’s close relations with DINA chieftain Manuel Contreras appear to have been withheld from them for some time.

The CHILBOM investigation of the assassination of Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt is the subject of two detailed accounts—Assassination on Embassy Row, authored by John Dinges and Saul Landau, and Labyrinth, by Taylor Branch and the lead assistant U.S. attorney in the case, Eugene Propper. To summarize: during the first year the investigation focused on the anti-Castro exile community in Miami—a community well-known to the FBI for its terrorist violence. Eventually, informants told FBI investigators that an exile group, the Cuban Nationalist Movement (CNM) had committed the crime at the behest of the Pinochet regime. The Justice Department submitted a set of questions to the Chilean government in mid-1977, and waited months while the Chilean government appointed an unwitting special investigator to pursue a response. Finally, in February 1978, the Justice Department presented an official “Letters Rogatory” to the Chilean regime, formally demanding evidence of contacts with Cuban exile terrorists, and seeking to question the two Chilean agents who had sought U.S. visas in Paraguay to travel to Washington in July 1976 before the assassinations took place. As part of the Letters Rogatory, U.S. officials submitted reproductions of the passport photos of Juan Williams and Alejandro Romeral—aliases for Michael Townley and Armando Fernández Larios—that had been copied by the then U.S. ambassador to Asuncíon, George Landau.

The break in the case came on March 3, 1978, after the FBI leaked those passport photos to reporter Jeremiah O’Leary who published them on the front page of the Washington Star.1 The pictures were immediately reprinted in the Chilean press. By March 6, multiple sources had identified the photo of Williams as one Michael Vernon Townley, an American living in Santiago.

As a U.S. citizen suspected of an act of terrorism in the United States, Justice Department officials immediately demanded custody of Townley. But Pinochet’s officials claimed no knowledge of him or his whereabouts, all the while secretly hiding Townley in his own home.2 FBI agents and assistant U.S. attorney Propper flew to Santiago to force the issue. Under intense diplomatic pressure, Chilean intelligence officials conceded that Townley was a DINA agent and in their custody. After significant stalling, the regime finally agreed to expel him if the United States publicly announced that Chile was cooperating in the investigation, and signed a formal accord limiting the information provided by Townley to use only in a criminal prosecution of the Letelier-Moffitt case.3

On April 8, Chilean authorities put Townley on an Ecuadorian airlines plane to Miami accompanied by two FBI agents. Under questioning, he provided U.S. authorities, and Chile’s special military investigator, Gen. Hector Orozco, with detailed evidence of the assassination plot. “Mr. Townley has implicated the highest officials of DINA in ordering Mr. Letelier murdered,” Propper would report in a secret memorandum to Ambassador Landau on April 25. His confession led to a U.S. indictment of three high-level Chilean intelligence officers—Contreras, his deputy Pedro Espinoza, and Fernández Larios—as well as five CNM members on August 1, 1978.4 In early September, Washington formally requested the extradition of the three DINA officials.

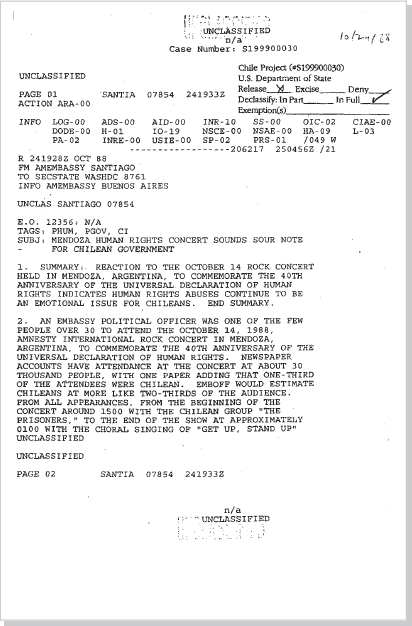

Revelations of the regime’s complicity in the Letelier-Moffitt assassination caused a major crisis in U.S.-Chilean relations, as well as a severe scandal in Chile. “The sensational developments have evoked speculation about President Pinochet’s survival,” CIA analysts wrote in a secret intelligence memorandum on “Chile: Implications of the Letelier Case.” (Doc 1) The threat to the regime came not from popular opposition, but rather from internal dissention within Pinochet’s power base—the Chilean military. Numerous military officials inside the government, who despised Contreras for his concentration of power and damage to Chile’s international image, believed that if Pinochet knew of the plot he should be ousted. A core group of military officers closely tied to DINA also opposed Pinochet—for not giving full support to Contreras, who, while no longer head of the secret police, was still the dictator’s closest military adviser. For Pinochet, the scandal threatened to become a Chilean Watergate.

General Pinochet clearly understood the precarious nature of his situation. During a toast to a house full of ambassadors at a diplomatic dinner he hosted on June 23, 1978, the general openly alluded to the possibility he might be forced to resign. In a report on the dinner titled “Conversation with Pinochet—He Talks of Going,” Ambassador Landau noted that during a twenty-minute private talk with the general later that evening

Pinochet, who normally drinks very little, had two scotch and sodas. His face grew redder and redder as he talked to me. At the end he was somewhat aggressive. He appeared a deeply troubled man and his concern that he might be replaced by other military officers seems to be foremost in his mind.

Recalled to Washington several days later, Landau alerted the National Security Council staff that “we are approaching the end of the road in U.S.-Chilean relations and it is only a matter of time before the Army leadership realizes that the only way Chile will improve its relations with the rest of the world is by replacing Pinochet.”5 But his predictions of the demise of the Pinochet regime proved to be premature.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1978 General Pinochet pursued a calculated four-point strategy designed to cover up his regime’s act of international terrorism and protect those who had perpetrated it. His action plan, the CIA Station learned, was to:

A. Protect General Manuel Contreras from successful prosecution in the murder of Letelier, since Pinochet’s political survival is dependent upon Contreras’ fate.

B. Stonewall any further requests from the U.S. government that would serve to build a case against Contreras and other Chileans.

C. Continue to “lobby” the Supreme Court justices to insure that requests for extradition of Chilean citizens following anticipated indictments are rejected.

D. Continue to exploit Chilean nationalism with a covert action campaign to portray the Letelier investigation as being politically motivated—another pretext for destabilizing the Pinochet regime. (Doc 2)

Key to Pinochet’s survival was his ability to distance himself from Manuel Contreras—the dictator’s closest advisor and the one person who could tie Pinochet directly to this act of terrorism. Only Contreras knew the details and degree of Pinochet’s involvement in authorizing and instigating the Letelier assassination. Few would doubt—and most would assume—that if Contreras authorized this crime, he assuredly did so with Pinochet’s explicit approval. According to the CIA’s early assessment in May:

Clouding the outlook for Pinochet is the possibility that former intelligence chief General Manuel Contreras will be linked directly to the crime. Public disclosure of Contreras’ guilt—either through his own admission or in court testimony—would be almost certain to implicate Pinochet and irreparably damage his credibility within the military. None of the government’s critics and few of its supporters would be willing to swallow claims that Contreras acted without presidential concurrence. The former secret police chief is known to have reported directly to the President, who had exclusive responsibility for [DINA] activities.

Loyalty to Pinochet, the CIA analysts added, was “no guarantee that Contreras would withhold sensitive details on operations authorized by the President, especially if he thought he were being tagged as a scapegoat.”

Indeed, CIA sources inside the Chilean military soon reported that Contreras had taken steps to secure his own immunity—and to safeguard Pinochet’s—by packing up DINA records that implicated Pinochet and clandestinely sending them out of the country. On April 20, according to one informant, Contreras shipped what was described as “a large number of suitcases” rumored to contain DINA documents on the freighter Banndestein, bound from Punta Arenas to an unknown European location.6 Contreras, another source would later inform U.S. military personnel, had taken “extreme precautions to protect President Pinochet from direct involvement in the decision-making/authorization process” in Chilean acts of international terrorism. In an intelligence cable entitled “Contreras Tentacles,” the DIA reported that

All government documents pertaining to the Letelier-Moffitt assassinations in Washington in 1976 as well as the killing of Pinochet’s predecessor as Army CINC, General Carlos Prats, and wife in Buenos Aires and the attempt on the life of regime opponent Bernardo Leighton in Rome in 1975, were removed by Contreras from DINA archives. . . . Contreras made two copies of each document, forwarding one to Germany and one to Paraguay for safe keeping while retaining the original under his control, in storage, in the south of Chile.7

Contreras used this evidence to protect himself, even as Pinochet tried to separate his government from the former DINA chieftain. Facing enormous pressure to mollify critics inside and outside of Chile, on March 21 Pinochet arranged the hasty resignation of Contreras from the Chilean armed forces. The Chilean army issued a perfunctory statement that Contreras had voluntarily withdrawn from active duty. But Pinochet and Contreras clearly had a secret agreement: Contreras would be protected from prosecution; in turn he would keep his knowledge of Pinochet’s role to himself and help orchestrate a massive cover-up.

That cover-up began in earnest after the Chilean military investigator, Gen. Hector Orozco, returned to Santiago from debriefing Townley in Washington in the late spring of 1978. In statements to Orozco, Espinoza and Fernández Larios confirmed Townley’s story. Orozco then confronted Contreras with evidence of DINA’s responsibility for the car bombing. On June 23, 1978, the same day that Pinochet told Ambassador Landau that his government was making a “sincere attempt to get to the bottom of the Letelier murder,” CIA sources described what happened:

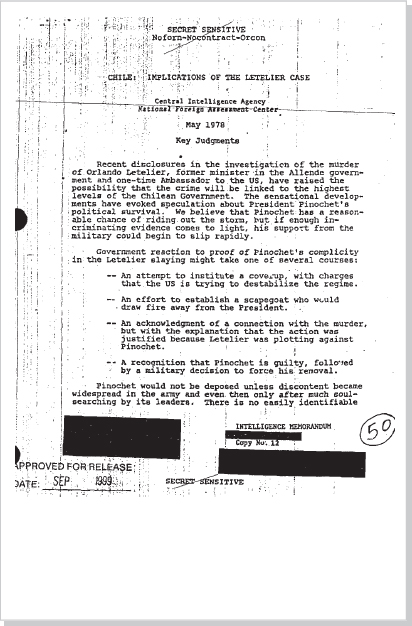

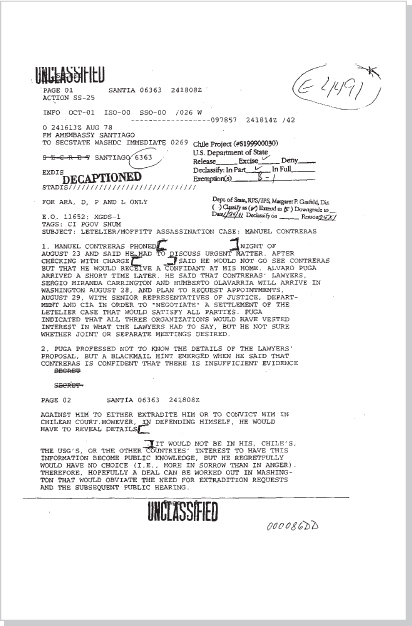

Contreras admitted his culpability, but threatened to claim that he was acting on orders from Pinochet in the event he was prosecuted. Contreras claimed he had safely secreted documentation to support his claim. This blackmail threat worked. Orozco was obviously given orders by Pinochet to accept Contreras’ cover story (that he had sent Townley and Captain Armando Fernández Larios to the U.S. merely to investigate Orlando Letelier’s activities—and that Townley had obviously exceeded his instructions). . . . Thus the coverup began. (Doc 2)

Thereafter, General Orozco pursued no further investigation. Instead, he became a coordinator of the cover-up. In October, he destroyed the truthful statements of Espinoza and Fernández Larios; Orozco then directed them to deceive the Chilean Supreme Court in their October 17 testimony.

Pinochet personally made sure that the Supreme Court would reject any U.S. extradition request. As early as May 31, 1978, the CIA obtained high-level intelligence on “Pinochet intercession w/Sup Crt to Prevent Extradition of Officials re: Letelier.”8 In June the CIA’s Santiago Station reported, “Pinochet, acting through his legal advisor Hugo Rosende, has manipulated the Supreme Court judges and now is satisfied that the court will reject extradition of any Chileans indicted.”

Pinochet’s personal involvement in obstruction of justice also included witness tampering. When Fernández Larios, who had spied on Letelier to provide intelligence for the assassination mission, decided he wanted to go to Washington and confess to U.S. officials, Pinochet summoned him to the Defense Ministry and ordered him to stay silent. “I know you want to go to the U.S.,” Pinochet told him. “Be a good soldier. Wait till everything’s all right. A good soldier remains at his post. Tough it out and this problem will have a happy end.” This order, U.S. investigators would later conclude, “directly implicates Pinochet who was directing the cover-up.”9

Contreras’s Blackmail Bid

The cover-up also included a massive nationalist propaganda campaign to convince Chilean citizens, as sources told the CIA, that Washington was “using the investigation into the Orlando Letelier assassination as a tool to destabilize the Chilean government.”10 To rally public support, Pinochet himself undertook a political tour, denouncing Washington for interfering in Chile’s internal affairs. The propaganda campaign went beyond blaming the U.S. for meddling; the regime sought to blame Washington for the actual assassination.

With mounting evidence of DINA’s involvement, Contreras planted the idea in the Chilean press that the CIA, not Chile, had engineered the car bombing. Throughout the summer of 1978, Contreras, his lawyers, and other Chilean officials repeatedly painted Townley as a CIA agent assigned to infiltrate DINA and embarrass the regime. Ominous hints about a “foreign ambassador” facilitating Townley’s effort to go to Washington were also fed to Chilean reporters.

These arguments were bolstered by several convenient facts: Townley was a U.S. citizen who had, in fact, tried to join the CIA; the U.S. embassy in Paraguay had provided him and Armando Fernández Larios with visas to travel to Washington ostensibly to see CIA deputy director Vernon Walters.11 Even more conveniently for Contreras’s ability to confuse the Chilean public, the ambassador who had signed those visas, George Landau, was now ambassador to Santiago.12 “Contreras plans to base his defense on the premise that Michael Townley and the Cuban exiles implicated were all under CIA control, and that the Agency ordered Letelier’s assassination to throw blame on Pinochet and thus topple him. He also plans to implicate Ambassador Landau in this scheme,” a CIA report warned headquarters. “While this defense is of course fabricated completely of whole cloth, it could cause us embarrassment.”13

In Washington, U.S. officials spent considerable time discussing the Contreras problem. At an August 21 meeting between Justice, CIA, and State Department officials, U.S. Attorney Eugene Propper laid out “three basic areas of concern: Contreras’ relationship [with the CIA], the issuance of U.S. visas for Paraguayan passports . . . and the relationship of ‘Condor’ to the case.”14 The same group of officials met the next day at the office of the CIA general counsel to review two short reports the Agency had prepared—one on Operation Condor, and the other on the top-secret history of CIA liaison relations with Contreras and collaboration with DINA.15

At this point, Contreras decided to supplement his public effort to implicate the CIA with a private threat to reveal his knowledge of, and involvement in, joint CIA-DINA covert operations directed at neighboring Latin American countries. On the evening of August 23, he placed a phone call to the home of Santiago Station chief Comer “Wiley” Gilstrap—or his deputy—asking to discuss an “urgent matter.” The CIA official agreed to receive a Contreras “confidant,” Alvaro Puga, at his house.

Puga suggested that two of Contreras’s lawyers, Humberto Olavarria and Sergio Miranda, would go to Washington at the end of August and “negotiate” a settlement in the Letelier case with the CIA, State, and Justice Departments. As the Station officer related the conversation to Ambassador Landau, “a blackmail hint emerged.” Puga stated that if forced to defend himself, Contreras would

have to reveal details [two lines deleted]. It would not be in his, Chile’s or the USG’s, or the other countries’ interest to have this information become public knowledge, but he regretfully would have no choice. Therefore, hopefully a deal can be worked out in Washington that would obviate the need for extradition requests and the subsequent public hearing. (Doc 3)

The blackmail threat, one U.S. official familiar with these communications remembered, was that if the Carter administration pursued the Letelier case, Contreras would expose previous CIA espionage operations toward a specific country in which DINA had collaborated.16 A few weeks later, the embassy learned that Contreras’s media game plan would include “revelation of close ties between the DINA and the CIA in the past, with names and supporting evidence.”17

To their credit, neither State Department nor CIA officials were intimidated or deterred by this bald gambit. “I said ‘Fuck Pinochet,’ ” recalled Francis McNeil, the ARA official principally responsible for the Letelier-Moffitt case in 1978.18 With the CIA’s agreement, McNeil drafted a cable to the embassy for the Station to use in responding to Contreras. “We told them in no uncertain terms that we would not submit to blackmail,” McNeil informed the Defense Department, warning that Contreras might try and approach U.S. military officials in Chile, “and that no representatives or either State or CIA would meet with Contreras representatives.”19 Contreras could “say anything he wants,” McNeil assured Assistant U.S. Attorney Propper. “But we’re going after him.”

Tepid Response to Terrorism

On September 21, 1978—the second anniversary of the car bombing—the U.S. Justice Department presented six-hundred pages of records and documents to the Chilean government as part of the formal petition, under the 1902 extradition treaty with Chile, to extradite Contreras and his subordinates. The Carter administration had overwhelming evidence of the regime’s responsibility and complicity. At the same time, SECRET/SENSITIVE documents described “detailed USG knowledge” of the regime’s efforts to “subvert Chilean legal procedures,” obstruct justice, and block extradition of the DINA officials. To redress an act of terrorism in Washington, the United States would have to overcome the Pinochet regime’s concerted effort to stonewall any investigation and cover up its involvement in this crime.

In great contrast to the forceful U.S. response to the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001, however, Washington’s reaction in the CHILBOM attack was weak and equivocal. The Carter administration’s counterterrorism policy fell victim to divisive bureaucratic competition, and a general lack of conviction to pursue justice and make the Pinochet regime pay a steep price for a terrorist act in Washington D.C.

Numerous mid-level officials in the State and Justice Departments did press hard for a comprehensive, forceful strategic response; as early as October 30, 1978, McNeil presented Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs Viron Vaky with a continuum of measures designed, as he wrote, “to give dominant priority to the Letelier/Moffitt case in the interests of justice and deterrence of other foreign intelligence agencies from similar assassinations.”20 But senior officials chose a less activist route, preferring to wait until the case cleared the Chilean Supreme Court, with the false hopes that if Chile did not extradite its DINA officials, the Pinochet regime would at least put them on trial in Santiago.

On May 13, 1979, the president of the Chilean Supreme Court, Israel Borquez Montero, handed down a preordained decision denying the U.S. extradition request. Townley’s confession was a “paid accusation,” Borquez ruled, because it was part of a plea-bargain agreement—all evidence derived from it was thrown out. The ruling essentially exonerated DINA of culpability for the Letelier-Moffitt assassination, although Borquez referred suspicions regarding false testimony by the DINA officials to a Chilean military court for further study.

“That decision was much worse than any one of us had anticipated,” the National Security Council’s Latin America specialist Robert Pastor alerted the President’s top security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski. U.S. policy toward Chile, he noted in a briefing memorandum, was “reaching the crunch point on Letelier.”21 Indeed, in Washington, the ruling created an immediate uproar in the executive branch, the press, and the Congress. One Congressional initiative, led by the chairman of the House Committee on Banking, Henry Reuss, called for terminating the regime’s economic lifeline—private U.S. bank loans that totaled over $1 billion—until the DINA agents were extradited. To express its diplomatic dissatisfaction, on May 16 the State Department recalled Ambassador Landau—for consultations on next steps as well as to convince Congress not to prematurely legislate sanctions against the Pinochet regime.

The Carter administration, however, responded with caution and relative inaction. The State Department decided only to appeal Borquez’s ruling to the entire Supreme Court and issue a diplomatic démarche warning of serious consequences for U.S.-Chilean relations if the ruling was not reversed. The internal policy debate focused on the wording and tenor of Ambassador Landau’s instructions on expressing U.S. dismay. At a May 24 interagency meeting chaired by Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher, Assistant U.S. Attorney Propper argued for a much more forceful approach. “We understand your position,” the State Department’s number three-man, David Newsom, told Propper. “But you must also understand that we have to take this matter in the context of our entire range of bilateral relations with Chile.” Propper’s response reflected his incredulity at such a passive reaction to international terrorism: “The Letelier case,” he noted, “is our relations with Chile.”22

To be sure, Ambassador Landau’s instructions did contain forceful language. When he returned to Santiago from Washington on June 2, Landau issued a statement at the airport rebuking the regime:

One should not lose sight that in this case U.S. sovereignty has been violated. And not by word but by deed. We should not forget that two persons, a former foreign diplomat and an American citizen, were killed in cold blood right in the heart of our nation’s capital. If this terrorist act is not a violation of our sovereignty, then I don’t know what is. We cannot allow terrorist acts of this nature to go unpunished.

Relations between Chile and the United States “are approaching a crossroads,” Landau warned; if the ruling stood and the DINA officials went free, the Chilean government would be held responsible for “harboring international terrorists” with all due consequences. “If these men walk the streets,” the démarche concluded, “I assure you that the reaction of my government, of the U.S. Congress, and of the American people will be severe.”23

In fact, on October 1, 1979, when the full Supreme Court not only upheld the Borquez ruling but overruled his recommendation for a military court investigation into possible perjury by Contreras and Espinoza, the Carter administration’s reaction was indecisive. Far from expressing outrage that an act of state-sponsored terrorism would now go unpunished, the U.S. government agencies with military, economic, and diplomatic interests in maintaining ties with Chile all began furiously lobbying to protect their bureaucratic turfs from becoming part of any forthcoming sanctions. At the White House, Brzezinski, along with Defense Secretary Harold Brown, opposed what they called “aimless punitive actions.” Even though the accumulated evidence had been used to convict the three Cuban exile terrorists in a U.S. district court earlier that year, some U.S. officials questioned the strength of the Justice Department’s case against the DINA officials. The result was a set of largely symbolic sanctions that had no impact on the Pinochet regime.

At the State Department, the Office of Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs (HA) led by Assistant Secretary Patricia Derian and her deputy Mark Schneider found itself waging a lonely battle for strong retaliatory measures. On the third anniversary of the crime, Derian sent a SECRET options memo to deputy secretary Warren Christopher laying out numerous proposals for sanctions. These ranged from the symbolic—pulling the Peace Corps out of Chile—to the substantive—“persuade private bank lenders to halt resource flows.” U.S. actions, she argued, should be strong enough “to demonstrate clearly that the governments engaged in international terrorism, and those harboring its perpetrators, will suffer penalties.”24 In an October 12 follow-up memorandum to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, Derian reiterated the need for “vigorous” sanctions “to deter further such government-supported assassinations and to reflect our outrage at this violation of our U.S. sovereignty.” Failure to take such steps, she added, “would strengthen Pinochet and those opposed to an accelerated return to democracy.”25

But State’s Latin America bureau, ARA, opposed substantive sanctions. The head of ARA, Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs Viron Vaky—the same official who had, eight years earlier, tried to persuade Kissinger not to pursue covert intervention against Allende—preferred not to compromise ongoing U.S.-Chilean bilateral relations. Vaky also opposed accepting the premise that the DINA agents were guilty. “I am disturbed by the too easy mindset and assumptions we get into of stating the defendants are guilty, are terrorists, and there is miscarriage of justice,” he wrote in an October 12 cover memo to Secretary Vance, transmitting a list of nineteen potential actions against Chile. “We should not be so self righteous and outraged, but careful and measured. . . . [W]e should react just coldly and not as an avenging angel, however good the latter makes us feel.” (Emphasis in original)

Vaky’s position found an ally at the National Security Council—Robert Pastor. “I have never been comfortable with the way State has handled the Letelier case,” Pastor wrote to Brzezinski after a preliminary draft list of sanctions landed on his desk on October 11. “I have been unable to comprehend the transformation of the U.S. from government to prosecutor to judge, which is where we currently are.” Pastor, who was deliberately kept out of the loop by Justice and State Department officials, informed Brzezinski that the State Department had failed to justify its rejection of the Chilean Supreme Court ruling. “That case may exist,” he wrote, “but I haven’t seen it yet, and I have asked repeatedly for it.”26

In an interagency meeting on October 15 to discuss sanctions against Chile, Pastor asked again, putting this question directly to Assistant U.S. Attorney Lawrence Barcella: “are we that confident in the evidence that we presented that we can say with assurance that the decision of the Chilean Supreme Court was in fact in error?” Barcella, who passed out autopsy photographs of the victims to remind the bureaucrats of the human nature of this crime, responded that the evidence was overwhelming.27 “We have unequivocal proof,” he told Pastor and thirty other officials, “of the most heinous act of political terrorism ever committed in the nation’s capital. We have proven that it was agents of a foreign power who carried it out. That foreign power has now blatantly rejected our request to see that justice is done, and it’s up to the people in this room to respond.”28

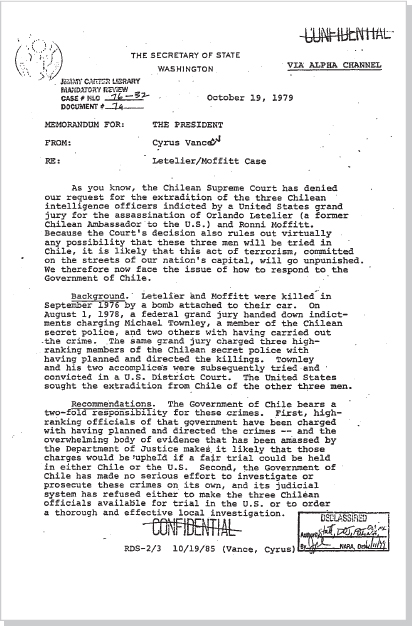

On October 19, Secretary Vance transmitted to President Carter—via a special “Alpha Channel”—the final State Department recommendations for sanctions against Chile. Nineteen options had been whittled down to six, among them terminating $7 million of military equipment still in the foreign military sales pipeline to Chile; ending the Overseas Private Investment Program (which had not operated in Chile since 1970); suspending Export-Import Bank credits; canceling export licenses for purchases by the Chilean military, and withdrawing all four members of the U.S. MilGroup stationed in Santiago. Gone were what Vance labeled “extreme measures” such as a cutoff of private bank loans, and an indefinite recall of the U.S. ambassador to Chile. “Steps of this sort,” he wrote the president, “would not serve our interests in Chile or elsewhere.” (Doc 4)

The White House decided to reduce the sanctions even further. On October 26, President Carter approved four of the six recommendations,29 and changed the proposal to withdraw the U.S. MilGroup to a simple reduction of two members.30 (In early 1980 an additional symbolic sanction, canceling Chilean participation in the UNITAS naval maneuvers, would be added.) The president, as Brzezinski wrote in a SECRET memo to Vance titled “Letelier/Moffitt Case and U.S. Policy to Chile,” had determined that these actions “would constitute a strong reaffirmation of our determination to resist international terrorism and a deterrent to those who might be tempted to commit similar acts within our borders.”

But the saga of the sanctions did not end there. For almost five weeks, administration officials delayed announcement of the U.S. response. Initially the delay was intended to avoid an adverse impact on Congressional consideration of a U.S. aid package for Latin America. Then, on November 4, the U.S. experienced another act of terrorism when Iranian fundamentalists swarmed the U.S. embassy in Teheran, taking the staff hostage and demanding that the Carter administration return the Shah, who had come to the U.S. for medical treatment. Vance again delayed announcement of the Chile sanctions, fearing that they could be used to bolster Iranian demands for extradition of the Shah. “The Chilean issue will not go away, and the longer the Iranian crisis goes on, the more likely people will begin drawing parallels between the two cases,” Pastor advised Brzezinski on November 19. In a SECRET/EYES ONLY memorandum titled “The Letelier Case—a Time to Reassess,” Pastor recommended “you speak to the President about reconsidering the decisions on Chile in light of the crisis in Iran.”

The sanctions were not reconsidered; but U.S. officials did redraft the language used to announce them. Instead of tying the measures to Chile’s refusal to extradite the DINA terrorists, the administration focused on the Pinochet regime’s “refusal to conduct a full and fair investigation of this crime.” At a press briefing on November 30, two full months after the Chilean Supreme Court ruling, White House press secretary Hodding Carter announced the measures, stating that the regime “has, in effect, condoned this act of international terrorism.” In his final comment the presidential spokesman noted that the press had made comparisons between the Letelier case and the ongoing Iranian hostage crisis. “There is only one link between those two situations,” he concluded. “Both involve egregious acts of international terrorism, and in both cases our responses reflect our determination to resist such terrorist acts, wherever they occur.”

Reagan and Pinochet

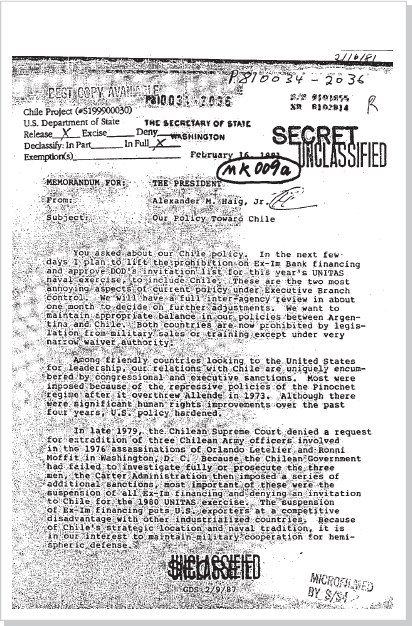

U.S. sanctions imposed on Chile lasted approximately one year.31 Soon after Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, in his very first policy gesture toward Latin America, his administration announced that it would rescind Jimmy Carter’s limited measures against the Pinochet regime. At the same time, Reagan’s new foreign policy team began working behind the scenes to restore positive U.S. relations with the regime. “You asked about our Chile policy,” Reagan’s secretary of state, Alexander Haig, wrote in a SECRET memo to the new president on February 16, 1981. “In the next few days I plan to lift the prohibition on Ex-Im Bank financing and approve DOD’s invitation list for this year’s UNITAS naval exercise, to include Chile. These are the two most annoying aspects of current policy under Executive Branch control. We will have a full inter-agency review in about one month to decide on further adjustments.” (Doc 5)

Ironically, Reagan had ridden a wave of public outrage against terrorism into the Oval Office. “It is high time that the civilized countries of this world made it plain that there is no room worldwide for terrorism,” he declared on the eve of his election. When it came to Chile, the White House made clear, there was a little room after all. The new president himself was a member of a small clique of right-wing ideologues who had shamelessly cast the victim as villain, and actively disseminated the regime’s specious “martyr theory”—that leftists carried out the car bombing. In 1978 Reagan used his nationally broadcast radio program to accuse Letelier of being an “unregistered foreign agent” with “links to international Marxist and terrorist groups.” As the future president told his listeners: “a question worth asking is whether Letelier might have been murdered by his own masters. Alive he could be compromised; dead he could become a martyr.”32 In testimony before Congress, Reagan’s new ambassador-at-large, Gen. Vernon Walters, rationalized the Letelier-Moffitt car bombing as “a mistake” comparable to Napoleon’s murder of the Duke of Enghien. As Walters summed up the new administration’s attitude: “You can’t rub their noses in it forever.”33

In the reconfigured political priorities of President Reagan and his advisers, Pinochet’s avid anticommunism far outweighed his violent atrocities. The fact that the regime had sponsored an act of terrorism on a Washington street, for these policy makers, did not make it any less pro-American. Indeed, Pinochet epitomized the “moderate autocrat friendly to American interests,” as the new U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick characterized “authoritarian” military rulers in her famous Commentary article, “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” which attacked Jimmy Carter’s policy on human rights.34 The Chileans could be counted on as an ideological ally in the battle against Soviet influence in the hemisphere and a supporter of a hard-line, militarist U.S. approach to revolutionary upheaval in Central America in the 1980s. In addition, Reagan officials saw Chile as a model for the free market, monetarist economic policies the administration intended to implement. “The Reagan administration,” Kirkpatrick declared in the summer of 1981, “shares the same convictions as the architects of Chile’s economic policy—that a free market approach will prove more effective in restoring fully the economic strength in the United States.”

After four years of tense relations with the Carter administration, General Pinochet viewed Washington’s renewed support as vindication and validation. The Reagan era, Chilean officials expected, portended an end to the country’s international isolation as a pariah nation. “Seven years ago,” Pinochet began telling Chilean audiences within two months of Reagan’s election, “we found ourselves alone in the world in our firm anticommunist position in opposition to Soviet imperialism, and our firm decision in favor of a socioeconomic free enterprise system.” Today, he declared, “we form part of a pronounced worldwide tendency—and I tell you, ladies and gentlemen, it is not Chile that has changed its position.”

The Reagan team moved quickly to embrace the regime, and normalize bilateral relations estranged during the four years of the Carter administration. Public pronouncements of U.S. friendship became frequent; in July 1981, the administration began voting in favor of multilateral bank loans to Chile—in contemptuous violation of the 1977 International Financial Institutions Act mandating a “no” vote on loans to governments that engage in a consistent pattern of human rights violations.35 At the United Nations, Ambassador Kirkpatrick now voted against a special human rights rapporteur to investigate abuses in Chile.

Diplomatic exchanges, unheard of since the days of Henry Kissinger’s warm support for the Junta, also increased significantly. In late February 1981, Reagan sent his special envoy General Walters to see Pinochet. Walters conveyed a private message from Secretary Haig, and briefed the dictator on U.S. counterinsurgency operations in El Salvador. “We spoke as old friends,” Walters reported back in a secret memorandum of conversation. “He was obviously very pleased to see me. He offered full support and said he would do anything we wanted to help us in the Salvadoran situation.”36 In August, Ambassador Kirkpatrick also traveled to Santiago, meeting with military and business leaders but avoiding pro-democracy and human rights groups. “We had a very pleasant tea,” Kirkpatrick told reporters as she emerged from a private meeting with Pinochet. “My conversation with the president had no other fundamental purpose than for me to propose to him my government’s desire to fully normalize our relations with Chile.” In an overview of her visit, the Santiago embassy cabled Washington that Pinochet had “responded immediately and warmly to the basic themes of her statements on the U.S. desire to rebuild cooperative and equitable ties.” In sum, the embassy reported, “Ambassador Kirkpatrick’s visit was extremely valuable in accelerating the return to cooperative relations.”

Repealing the Kennedy Amendment

Normalizing relations required removing the legislative bans on military and economic assistance to Chile. Through the spring and fall of 1981, the administration lobbied hard for repeal of the Kennedy amendment. Pinochet’s closest ally in the U.S. Senate, Jesse Helms, led the attack, brushing away arguments that Washington should not be providing military aid to a terrorist government. Letelier, he claimed without a shred of proof, was “an agent of terrorism.” On the floor of the U.S. Senate, Helms then proceeded to justify the assassination: “He who lives by the sword shall die by the sword.”37

The bill to repeal the Kennedy amendment passed, but with significant conditions on renewing U.S. military support to Pinochet. The final legislation, influenced by human rights lobbyists in the House of Representatives, stated that any U.S. weapons or equipment sales, credits or military services would require President Reagan to certify that:

• The government of Chile has made significant progress in complying with internationally recognized human rights.

• The government of Chile is not aiding and abetting international terrorism.

• The government of Chile has taken appropriate steps to cooperate to bring to justice those indicted in connection with the murders of Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt.

The Reagan administration had no problem certifying Chile on human rights grounds—despite the regime’s ongoing high-profile atrocities. On February 26, 1982, CNI agents brutally murdered Chile’s most famous trade union leader, Tucapel Jiménez, who was organizing a united labor front to oppose the regime’s economic and political repression; he was found shot in the head and garroted to the point of decapitation. Yet, only two weeks later Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs Thomas Enders traveled to Santiago to confer with Chilean officials and, according to one cable, “reiterated that the human rights question was not our immediate concern.”

But the certification clause on the Letelier-Moffitt case did cause immediate concern. Both the FBI and the Justice Department actively opposed certification of Chilean cooperation, and were quite willing to say so publicly. “They haven’t done spit,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Barcella told the Washington Post about Pinochet’s government. “In fact, they’ve been dilatory and obstructionist.” Barcella and his colleagues drafted a highly classified twelve-page catalogue listing the regime’s failure to cooperate and conduct its own investigation, and its multiple attempts, including the falsification of evidence, to obstruct the U.S. investigation. Privately, FBI and Justice officials warned the State Department that they would testify before Congress that any presidential certification was unfounded and false.

“You may or may not know that the DOJ seems strongly opposed to certification with respect to the Letelier case, as is the FBI,” then Assistant Secretary for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs, Elliott Abrams warned in an EYES ONLY memo to one of Secretary Haig’s deputies, Lawrence Eagleburger. “This seems to me to make it impossible to certify, for the only acceptable action on the part of the GOC might put half the [Chilean] government in jail.” Pressuring the Justice Department to change its position, Abrams counseled, would be a public relations disaster. “I don’t know whether there is anything the Chileans can do for us to satisfy the (foolish) demands of Congress,” he advised Eagleburger. “What I am sure of is that significant opposition in the DOJ exists and that any attempt to steamroller the DOJ will be extremely damaging front-page news.”38

Abrams joined a number of other bureaus in the State Department in recommending to Secretary Haig that the president not certify Chile along with Argentina, as Haig had planned in March 1982. A secret options memorandum—“Presidential Determinations Authorizing Security Assistance and Arms Sales for Argentina and Chile”—presented to the secretary by seven deputies and assistant secretaries, warned that the Chile certification “will be particularly controversial.” On improvements in human rights “there had been none since [1979].” The Letelier-Moffitt case posed even larger problems, the memo acknowledged. To claim Chile had cooperated in the pursuit of justice was “an extremely difficult proposition to sustain and to defend.” Some bureaus worried that the certification “would also weaken our emphasis on countering international terrorism.”

But there was an even larger issue for those opposing the Chile certification: compromising Reagan’s top foreign policy priority of escalating U.S. counterinsurgency operations in Central America. To sustain U.S. military involvement in the region, the administration had already sent one mendacious certification on El Salvador to an increasingly skeptical Congress, and was preparing another. “The recent certification on El Salvador was even more acrimonious and difficult than we had anticipated,” the authors reminded Haig. The Chile certification, particularly the clause on the Letelier-Moffitt case, would hurt the credibility of future appeals to lawmakers:

An important question is whether sending the Chile certification will so damage our credibility on human rights as to coalesce the [Congressional] opposition, and therefore have a dangerous spillover effect on our El Salvador policy and serve to discredit the President’s upcoming Caribbean Basin initiative.

This argument prevailed; the Reagan White House deferred certifying Chile. By the time the administration had finally achieved a consensus in Congress on massive intervention in Central America in 1986, however, U.S. policy interests in providing military assistance and sales to the Pinochet regime had been overtaken by events and there was a stronger policy posture against certification. As one internal State Department memorandum noted: “we do not believe Chile has met the criteria.”

Iran-Contra: The Chilean Connection

Ironically, the Reagan administration sought carte blanche on military assistance to Chile, in part as a way of enlisting Pinochet’s support in the Central American imbroglio. In 1980 and 1981, the Chilean regime provided substantive training and tactical advice to Salvador’s cutthroat military forces. (For Chile’s avid support, in May 1981 the Salvadoran high command bestowed the José Matias Delgado award on General Pinochet.) In Nicaragua, Chile was considered a potential ally in the National Security Council’s illicit pro-insurgency paramilitary campaign against the Sandinista government—particularly after the U.S. Congress cut funding for CIA support of the contra war in October 1984.

In late 1984, declassified White House memoranda reveal, Lt. Col. Oliver North, the NSC official in charge of sustaining the contras after the Congressional ban on the CIA, secretly turned to the Pinochet regime for a key weapons system: the British-made Blowpipe missile. The Sandinistas were attacking contra positions with sophisticated Soviet-provided Hind helicopters; North’s advisors told him that the contras needed these shoulder-held antiaircraft weapons. In a memorandum to the president’s national security adviser, Robert McFarlane, dated December 20 and stamped TOP SECRET, North wrote that he had been “informed that BLOWPIPE surface-to-air missiles may be available in [Chile] for use by F.D.N. [the largest contra group] in dealing with the HIND helicopters. This information was passed through an appropriate secure and source protected means to [contra leader] Adolfo Calero who proceeded immediately to Santiago.”

Entries in North’s notebooks indicated that Calero and his delegation were in Chile between December 7 and 17, 1984. On December 17, North recorded the following phone conversation with Calero:

Call from Barnaby [Calero’s code name]—Returned from Chile—48 Blowpipes, free-8 launchers, 25 K ea.—Have to inform Brts—6–10 pers[ons] for training, starts 2 Jan—Will have to buy some items from Chileans which are somewhat more expensive—Deliver by sea w/trainers by end of Jan. (Doc 6)

The Chileans, as North advised McFarlane, had offered forty-eight missiles, launchers, and training “for up to ten three-man teams from the FDN on a no-cost basis.” Calero, North added, “will dispatch the trainees to Chile on December 23.”

There was one complication, however. In his December 20 memo, titled “Follow-up with Thatcher re: Terrorism and Central America,” North noted that the Chileans had said “they would need to obtain British permission for the transfer” of the Blowpipes. North proposed having President Reagan discreetly ask British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to intercede on the contras’ behalf.

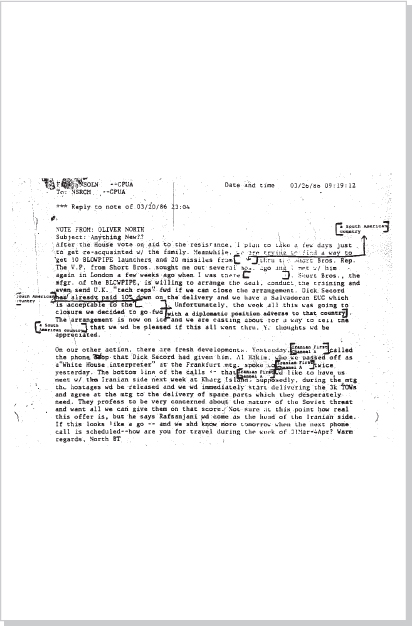

This first initiative to get missiles from Chile ran into additional complications. On January 3, 1985, according to North’s notebook entry for that day, Calero informed him that the Pinochet regime wanted to include ammunition and mortar rounds in the deal that were “too expensive.” As Calero put it, the “Blow-Pipe deal is off.” But additional attempts followed over the next fifteen months. Encrypted cables and secret e-mail messages between North and McFarlane’s successor, Admiral John Poindexter, show that throughout the spring of 1986, NSC officials tried to obtain a British reexport license for Chile to arrange a “quick transfer of 6–10 BP.” Their elaborate scheme called for Short Brothers, the Belfast-based manufacturer of the Blowpipe missile, to facilitate the transfer of the weapons from Chile to the contra forces through El Salvador, using falsified end-user certificates—a document required in major arms sales. An obscure entry under “current obligations” in the handwritten account ledger kept by North’s contra arms supplier for May 1986 reads BP $1,000,000 Chile, suggesting that a substantial payment was expected to be made on the Blowpipe deal. “[W]e are trying to find a way to get 10 BLOW-PIPE launchers and 20 missiles from Chile thru the Short Bros. Rep,” North reported to McFarlane over an encoded computer line on March 26 adding:

The V.P. from Short Bros. sought me out several mos. Ago and I met w/ him again. . . . Short Bros., the mfgr. of the BLOWPIPE, is willing to arrange the deal, conduct the training and even send U.K. “tech. reps” fwd if we can close the arrangement. Dick Secord has already paid 10% down on the delivery and we have a [country deleted] EUC [end-user certificate] which is applicable to Chile.

But the issue of Pinochet’s human rights atrocities came back to haunt this highly covert operation. Unaware of this secret approach to the Pinochet regime, the State Department inadvertently undermined the deal. “Unfortunately,” North continued, “the week all this was going to closure we decided to go fwd [deleted reference to the State Department decision, on March 12, to sponsor a United Nations resolution condemning the regime’s human rights abuses].” Pinochet’s officials were furious with what they considered as the Reagan administration’s betrayal.

“The arrangement is now on ice,” North told McFarlane, “and we are casting about for a way to tell the Chileans that we wd be pleased if this all went thru.” (Doc 7)39

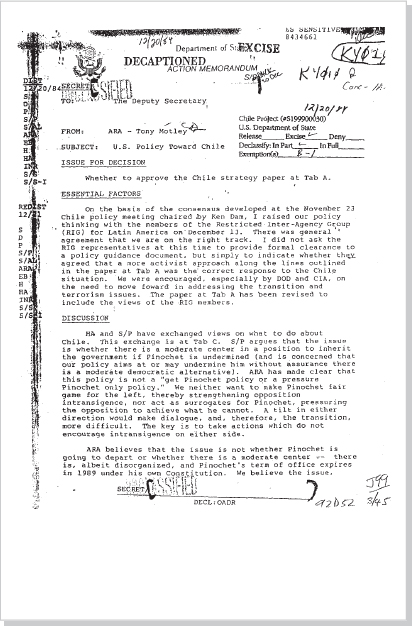

The Reagan administration’s sponsorship of a U.N. resolution critical of Chile’s human rights record marked a slow shift away from its early uncritical embrace of the Pinochet regime. Ironically, at the very moment North’s contra representatives were secretly seeking military assistance in Santiago, the State Department initiated a major internal policy review on Chile. On December 13, 1984, Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs Langhorne A. Motley held the first of three meetings with the RIG—a high-level Restricted Interagency Group made up of State, CIA, DOD, and NSC officials—to seek authorization to revamp U.S. policy toward Pinochet. On December 20th—the very same day as North submitted his request for Reagan’s help in obtaining British support for the transfer of the missiles from Chile—Motley presented a draft policy proposal to the Deputy Secretary outlining “an activist but gradual approach to try to influence an orderly and peaceful transition to democracy in Chile.” (Doc 8)

This reassessment was based on increasing instability in Chile, which set off alarm bells throughout a national security bureaucracy already obsessed with the upheaval in Central America. According to the policy paper:

U.S. interests would be best served by Pinochet’s leadership of a real and orderly transition to democracy. However, it is increasingly evident that Pinochet is unlikely to lead such a transition. While ostensibly serving U.S. anticommunist interests in the short run, Pinochet’s intransigence on democracy is creating instability in Chile inimical to U.S. interests.

Fostering a moderate center in Chilean politics, Motley stated in a familiar refrain, would be key to protecting long-term U.S. interests. The aim of a new U.S policy approach would be “strengthening the disorganized [Chilean] moderates, specifically, weaning them away from the radical left.”

Pinochet’s protracted crisis of power created the catalyst for U.S. concerns. As CIA analysts summed up the situation in a succinct 1984 intelligence report, “Pinochet Under Pressure,” the Chilean political scene had changed, “irreversibly we believe,” over the last two years:

• Public attitudes toward the government’s free market policies have been soured by a recession.

• Trade unions and political parties have undergone a revival that has brought political life back to Chile.

• Radical leftists have become more politically active—holding public meetings and participating in informal discussions with moderate parties—and the Chilean Communist Party has developed a nationwide organizational base that is second only to the Christian Democratic Party.

• The number, sophistication, and boldness of radical leftist terrorist attacks have escalated dramatically in the last ten months, prompting . . . an increase in right-wing extremist attacks against political opposition figures.

• Military solidarity with Pinochet has suffered its first strains over differences in how to handle political dissent and the timetable for returning Chile to civilian rule.

The military regime’s problems began in mid-1982 when the country suffered its worst economic recession since the Great Depression. Gross national product plummeted by 14 percent; unemployment rose to 30 percent. Chile’s foreign debt reached $19 billion, then the highest per-capita debt in the world. The “economic miracle” created by the University of Chicago-trained students of free market guru and regime adviser Milton Friedman, was discredited.

The economic crisis reinvigorated the opposition to Pinochet, which increasingly included members of the conservative upper middle class hit hard by financial losses. Across the social spectrum, political parties, human rights organizations, trade unionists, and church groups all began the arduous task of mobilizing a national coalition to end military rule and restore democracy.40 On May 11, 1983, the opposition held the first “national day of protest” that El Mercurio called “the most serious challenge which the government has faced in almost ten years.” Thereafter, major street demonstrations and other displays of organized public discontent became frequent. At the same time, the Chilean Communist Party (PCCH) began a major campaign to regroup and revitalize its constituents. The more militant wing of the PCCH created an armed faction, the Manuel Rodriguez Patriotic Front, which carried out attacks on government installations. On September 7, 1986, the Patriotic Front boldly attempted to ambush and assassinate General Pinochet.

The regime responded to these manifestations of opposition by attempting to siphon off the moderate civilian leaders while unleashing the military’s apparatus of repression. Between May and September 1983, eighty-five people were shot and killed; over 5,000 arrested. At the same time, Pinochet reshuffled his cabinet and appointed a well-known moderate conservative, Sergio Jarpa, as interior minister. He authorized Jarpa to hold a dialogue with moderate political parties regarding the 1980 constitution that the Junta had pushed through to legitimize Pinochet and gave him the opportunity to extend his personal dictatorship to the near end of the century.

Pinochet cast his 1980 constitution as providing a “protected” and “safe” transition back to democracy. Its provisions allowed for him to hold a “Yes/No” plebiscite in 1989 on a military candidate put forth by the Junta to be president until 1997—the candidate being Pinochet himself. In the extremely unlikely event that the no vote won, according to the constitution, Pinochet would remain in power for another seventeen months until controlled elections for a civilian president and Congress were held. Thereafter, he would remain commander-in-chief of the armed forces until 1997. The military would be given a set of seats in the new Senate and would continue to control policy through a National Security Council with widespread powers.

The opposition, including the centrist political parties, rejected the 1980 Constitution as illegitimate: it had been drafted by the military and voted on in a heavily manipulated plebiscite that was neither free nor fair. As the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence acknowledged in a comprehensive report, the regime had left “no stone unturned” in assuring the passage of the Constitution, “resorting to extensive intimidation of opposition groups, arbitrary measures to undercut the efforts of those advocating a no vote, and at least some fraud during the balloting and tabulation of the votes.”41 In Jarpa’s dialogue with a coalition of noncommunist political parties called the Democratic Alliance, opposition leaders pressed for an accelerated timetable for the restoration of democracy, and called for Pinochet to resign and the secret police to be disbanded. The regime refused to yield on any opposition demands, and the dialogue disintegrated. In late 1984, Pinochet declared a state of siege under which the CNI escalated its brutal political assassinations of leftist leaders; in February 1985 he fired Jarpa and ended any effort at negotiations with pro-transition forces.

The Reagan administration now faced a dilemma similar to the one its predecessor confronted in Iran and Nicaragua—how to handle a stagnating, belligerent, and isolated dictatorship now an embarrassment, and increasingly a danger, to U.S. political and international interests. For Washington, the situation had implications that reached beyond Santiago, extending to Central America, Europe, and Capitol Hill.

In the administration’s relations with Congress, Chile had become a major liability. The Pinochet regime had made a mockery of Reagan’s claims that “quiet diplomacy,” reinforced by cozy relations, would prove effective in advancing the cause of human rights. The results weakened the credibility of similar arguments administration spokesmen made virtually every week on El Salvador and Guatemala. More importantly, the Chile policy revealed the utter hypocrisy of the administration’s pressure on Congress to provide tens of millions in paramilitary assistance for the contra war in the name of promoting democracy in Nicaragua, while failing to take any active steps to press Pinochet for a return to civilian rule. Numerous Congressmen, and a number of European allies troubled by U.S. policy in both Central America and Chile, cited this “double standard” in Reagan’s approach to Pinochet. Not until March 1986, after the collapse of two other long-standing U.S. client regimes—Marcos in the Philippines and Duvalier in Haiti—did the president vow to “oppose tyranny in whatever form, whether of the left or the right.”

Topping the list of policy concerns, however, was that Pinochet’s intransigence with the centrist opposition had fostered instability and insurgency, helping to revitalize the very leftist forces in Chile that the regime, with U.S. support, had sought to brutally eradicate. In the State Department’s policy review, officials underscored this point:

the failure of pro-transition forces in the GOC, both military and civilian, and pro-negotiation forces in the opposition, to reach an understanding during the past fifteen months, has created conditions favorable to the apparent attempt by the PCCH to launch an armed, Tupamaros or Montoneros-type insurgency in Chile. Continued delay in reaching such an agreement will encourage the PCCH in its policy of violent opposition to Pinochet.

During a four-day trip to Santiago in mid-February 1985, Assistant Secretary Motley privately told the Chilean dictator that “if he [Pinochet] were writing the script for the Communists, he couldn’t write it better than he was doing then.”42

Motley’s trip was supposed to be the first salvo in a new U.S. policy effort to press Pinochet to find common ground with the noncommunist opposition on negotiating a transition. But the assistant secretary’s warm public endorsements of the regime overshadowed whatever private pressure he brought from Washington. In an interview with El Mercurio, he stated the world owed Chile “a debt of gratitude” for overthrowing Allende. At an airport press conference as he left, he noted that the “future of Chile is in Chilean hands, and from what I’ve seen those are good hands.” The Motley visit, according to a subsequent State Department assessment, “was probably a net plus for Pinochet and resulted in no increased leverage for the U.S. on the transition.”

In his own after-action report to Secretary of State George Shultz, Motley shared several superficial conclusions: Pinochet was “as formidable a head of government as we face in this hemisphere”; “Pinochet does not respond to external pressure”; “Chile and therefore our interests are headed for trouble over the long haul.” He offered only vague “ideas on how maybe we can quietly help influence the situation internally.” As ARA assistant secretary, his position was to continue to use “quiet diplomacy” to gently nudge Pinochet and the military. In his memorandum to Shultz, Motley complained that public criticism by Assistant Secretary for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs Elliott Abrams was “not in consonance with agreed-to U.S. policy,” and could “only exacerbate the situation.”43

Within a few months, however, Abrams replaced Motley as assistant secretary for inter-American affairs. Under Abrams, who also assumed a key policy role in the illegal contra resupply operations, the U.S. approach to Chile focused more aggressively on pressing elements of the military government toward a transition. To put the regime on notice, Washington began abstaining on votes on multilateral development bank loans; in internal memoranda, Abrams claimed credit for using this tactic to convince the regime to lift the state of siege in June 1985. At the same time, through stepped-up contacts and communications, Washington sought to separate the Christian Democrats from the leftist opposition, and push them into collaboration with the rightist civilian political interests. U.S. policy makers enlisted the AFL-CIO to back non-Marxist labor unions in Chile. Washington also approached the British, Germans, and the Vatican to coordinate influence and pressure on the Chilean military and centrist and center-right politicians.

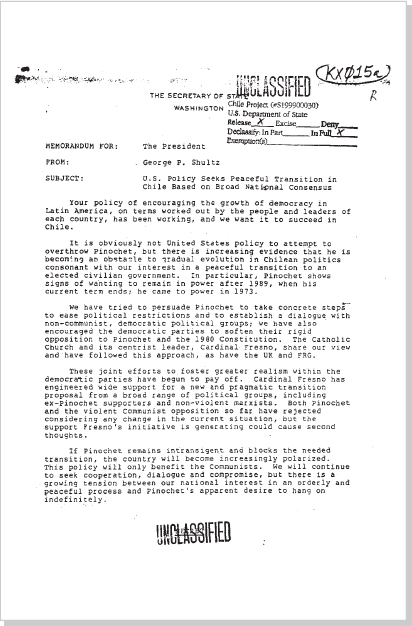

In an Oval Office meeting on September 6, 1985, Secretary of State Shultz briefed President Reagan on the policy now being implemented in his name. “We are not trying to overthrow Pinochet,” Shultz told the president, according to his talking points. “[B]ut there is increasing evidence that he is becoming an obstacle to the gradual evolution in Chilean politics that would favor our interest in a peaceful transition to a civilian elected government.” Pinochet’s intransigence would lead to Chile becoming “increasingly polarized,” Shultz explained, which would “benefit the Communists.” The United States would “continue to seek cooperation, dialogue and compromise,” he assured Reagan, according to a memorandum prepared for the meeting, “but there is a growing tension between our national interest in orderly and peaceful transition and Pinochet’s apparent desire to hang on indefinitely.” (Doc 9)

In the fall of 1985, the Reagan administration used the appointment of a new ambassador to Chile, Harry Barnes, to make a stronger and more open statement about U.S. support for a return to civilian rule. When Barnes presented his credentials to Pinochet in mid-November, he pointedly remarked, “The ills of democracy can best be cured by more democracy.” He then gave Pinochet a personal letter from Ronald Reagan. The letter reviewed the support and cooperation the administration had given to the regime since 1981, but noted that future cooperation would be conditioned by definable progress toward a democratic transition. “Just as in Central America the full exercise of personal and political liberties has helped the struggle against Communist subversion, progress in Chile will be similar aid,” the U.S. president wrote to Pinochet. “I feel even more strongly than ever that evident progress toward full democracy in Chile is needed.”

Rodrigo Rojas

The murder by immolation of a Chilean teenager, Rodrigo Rojas, drove the final wedge between Washington and the Pinochet regime. Rojas was a legal American resident; he had come to Washington D.C. in 1977 at age ten as a refugee with his younger brother and mother, Veronica De Negri, herself a torture victim and political prisoner after the coup. For eleven formative years, Rojas grew up in the activist Chilean exile community in the nation’s capital, involving himself in numerous human rights and solidarity activities against the Pinochet regime. He became an avid and skilled amateur photographer, and developed a fascination for Jane’s Defense Weekly and encyclopedias on armaments and military equipment. He was a dear friend of mine.44 I knew him to be smart and confident, curious but cocky—and very impulsive as teenagers are wont to be. As he grew older, he became increasingly agitated about returning to his homeland.

In May 1986, Rojas dropped out of his last semester at Woodrow Wilson High School, and returned to Santiago to do freelance photography and participate in the growing opposition to the regime. On July 2, he joined a student street demonstration in the barrio of Los Nogales to photograph the protest movement. Rojas and another protester, Carmen Quintana, were intercepted by an army street patrol. As doctors who later treated them at a neighborhood clinic told U.S. embassy officials:

Soldiers surrounded them and began to beat them. It is reported that the beating was severe and that Rojas attempted to shield Quintana. The soldiers then sprayed them with a flammable substance and set them on fire. The soldiers then wrapped blankets around them, threw them into a military vehicle, drove them to the town of Quilicura, just north of Santiago, where they threw them out of the vehicle into a ditch. They were then sighted by a passerby.45

Both Rojas and Quintana survived the initial beating and burning. They were taken to a small clinic, the Posta Central, where their treatment was described as “archaic and insufficient.” The director of the clinic, under pressure from the military, prevented them from being transferred to a fully equipped burn unit at a major hospital. After four days of inadequate care, at 3:50 P.M. on July 6, nineteen-year-old Rodrigo Rojas died.46

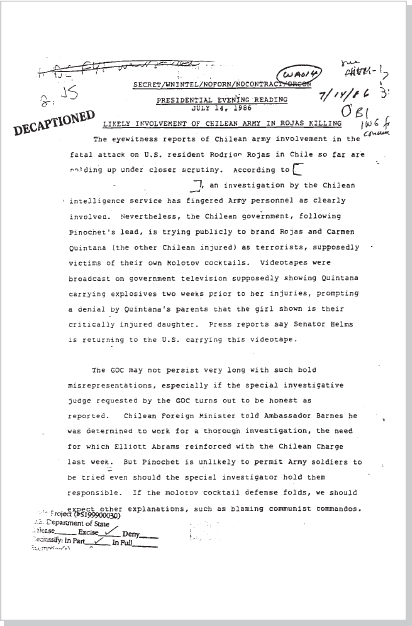

The horrific nature of the crime, and the fact that Rojas was a resident of Washington transformed this atrocity into an international human rights scandal. The case of Los Quemados—the burned ones—provoked an outrage around the world, and sent a “shock wave” through Capitol Hill, as classified State Department memos admitted, reinvigorating harsh criticism of the regime. The case received so much media coverage that even President Reagan was briefed on developments. In a “Presidential Evening Reading” paper, classified SECRET/WNINTEL/NOFORN/NOCONTRACT/ORCON, Reagan was informed that Pinochet had labeled Rojas and Quintana “terrorists” and “victims of their own Molotov cocktails,” even as Chile’s own intelligence service “has fingered Army personnel as clearly involved.” (Doc 10)47 An internal investigation by the Chilean Carabineros quickly identified the army patrol and its commander, Lt. Pedro Fernández Dittus, as responsible, sources reported to the embassy. But Pinochet personally rejected any evidence of the military’s guilt.48 His regime soon set out to intimidate all witnesses that could identify the army personnel. “One eyewitness was briefly kidnapped, blindfolded, and threatened if he did not change his testimony,” the DIA reported in a TOP SECRET RUFF UMBRA cable. “Some members of the government will quite likely continue to intimidate the witnesses in order to persuade them to change their testimony, thereby clearing the military.”

In a symbolic gesture of protest against the regime, Ambassador Barnes and his wife joined Veronica De Negri in attending the Rojas funeral on July 11. During the burial procession, Barnes and 5,000 mourners were assaulted with water cannon and tear gas from military units to disperse the crowd. To add insult to injury, the government then planted accusations in the press that the Barnes’s presence at the funeral had incited rioting. In the midst of the uproar, Pinochet further thumbed his nose at Washington by publicly announcing that he intended to stay in power through to the end of the century.

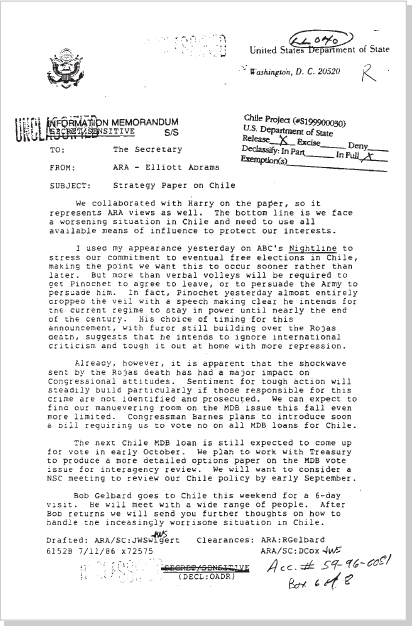

With the Rojas case, the breach of political relations between the U.S. and Pinochet reached a point of no return. On July 10, Assistant Secretary Abrams appeared on the ABC news program Nightline and issued the harshest public criticism to date from any Reagan administration official. “Fundamentally, the most important thing to say is that this is not an elected government,” he told Ted Koppel. “I think there are very good grounds to be very skeptical that President Pinochet wants any kind of a transition. . . . We don’t want to see it happen in the next millennium. We’d like to see it happen a little bit sooner than that.” In a SECRET/SENSITIVE memo to Secretary Shultz, Abrams reported that “I used my appearance yesterday on ABC’s Nightline to stress our commitment to eventual free elections in Chile . . . sooner rather than later. But more than verbal volleys will be required to get Pinochet to agree to leave, or to persuade the Army to persuade him.”

The “bottom line,” as Abrams concluded, “is we face a worsening situation in Chile and need to use all available means of influence to protect our interests.” (Doc 11)

Pinochet’s Endgame: Voting Down the Regime

On February 2, 1988, fourteen of Chile’s political parties announced the creation of a unified coalition—the Concertacíon de Partidos Para el NO—intended to defeat Pinochet in the upcoming plebiscite called for by the regime’s 1980 constitution. The deck was stacked against the opposition; the military controlled the media and the ballot box, and held extreme coercive powers over the Chilean citizenry. Political leaders would be arrested; opposition rallies would be broken up by force; offices of the “NO” would be set on fire. But even under campaign and voting rules written, violently imposed, and controlled by the regime, the plebiscite still represented the best opportunity to peacefully rid Chile of Pinochet’s fifteen-year-old dictatorship.

The effort to unite around one common goal marked a historic moment of cooperation among Chile’s historically divided, and divisive, right, center, and left political leadership. The Communist Party, and several radical factions of the Socialist Party were excluded from the Concertacíon; but many Marxist leaders also called on their constituents to organize in support of what came to be called the “Command for the NO.” A former Allende protégé and future Socialist Party president, Ricardo Lagos,49 became a key campaigner for the NO; a senior Christian Democrat, Patricio Aylwin, became the command’s designated spokesman, and another member of the PDC, Genero Arriagada, brilliantly managed the campaign. The opposition organized a comprehensive and extremely successful voter registration drive, registering over 92 percent of the eligible electorate by August 30, 1988. The Command for the NO also recruited poll watchers at all 22,000 voting tables and set up a secret computer system to assure that vote tallies would be rapidly transmitted to Santiago for independent tabulation and verification on October 5—D-day for the pro-democracy forces in Chile.

The Reagan administration channeled funds into the opposition campaign through the National Endowment for Democracy (NED)—a quasi-government entity set up to overtly supplement CIA covert funding of groups fighting to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua—as well as the AFL-CIO and the National Democratic Institute. Some $1.6 million went into the registration drive, voter education, opinion polling, media consultants, and organizing a rapid response parallel vote count on the day of the election. Ambassador Harry Barnes vigorously and openly supported the civic organizations that carried on much of the work to garner electoral support for the NO. The pro-Pinochet press began referring to him as “Dirty Harry.” Campaigning to extend his dictatorship through 1997, General Pinochet issued repeated denounciations of “Yanqui imperialism” in Chile.

Washington’s most significant actions during the plebiscite were its intelligence operations and diplomatic efforts to track and counter Pinochet’s plans to nullify the plebiscite, if he lost, through acts of violence. As early as May 1988, the CIA learned, elements of the Chilean army had concluded that the NO could not be allowed to win. A chief concern, the Station reported in a heavily censored cable titled “The Increasing Resolve within the Military to Avoid a Civilian Government in Chile,” was the regime’s record of terrorism and human rights violations. There was a “great fear that a civilian government would cooperate with the United States Government in pursuing the case of the assassination of former foreign minister Orlando Letelier,” the CIA noted, “as well as other abuses by the military, to the extreme detriment of the Chilean Army.”

By late September, polls indicated that the NO campaign had surged ahead as Chileans became confident that safeguards, including hundreds of international election observers, would insure a non-fraudulent election. “Public perception of the ‘NO’ is increasingly that of a winner,” the embassy reported on September 29. The next day, however, Ambassador Barnes sent the first “alerting” cable to Washington on information he had received regarding an “imminent possibility of government staged coup” if the vote went against Pinochet.

Both CIA and DIA intelligence provided what Ambassador Barnes characterized as “a clear sense of Pinochet’s determination to use violence on whatever scale is necessary to retain power.” In a secret report for Assistant Secretary Elliott Abrams, Barnes summarized Pinochet’s scheme:

Pinochet’s plan is simple: A) if the “Yes” is winning, fine: B) if the race is very close rely on fraud and coersion: C) If the “NO” is likely to win clear then use violence and terror to stop the process. To help prepare the atmosphere the CNI will have the job of providing adequate violence before and on 5 October. Since we know that Pinochet’s closest advisors now realize he is likely to lose, we believe the third option is the one most likely to be put into effect with probable substantial loss of life.50

Highly placed U.S. intelligence sources within the Chilean army command provided additional details. A Defense Intelligence Agency summary, classified TOP SECRET ZARF UMBRA, reported that

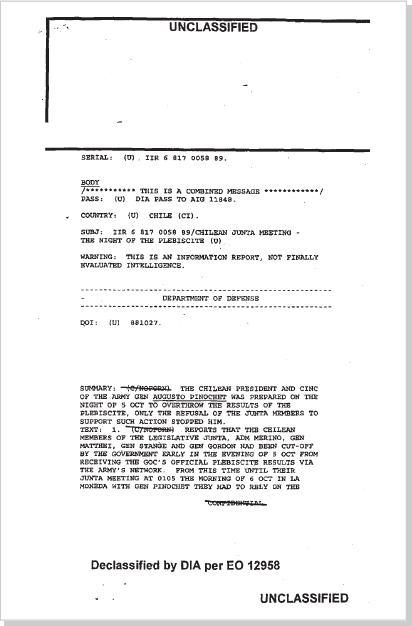

Close supporters of President Pinochet are said to have contingency plans to derail the plebiscite by encouraging and staging acts of violence. They hope that such violence will elicit further reprisals by the radical opposition and begin a cycle of rioting and disorder. The plans call for government security forces to intervene forcefully and, citing damage to the electoral process and balloting facilities, to declare a state of emergency. At that point, the elections would be suspended, declared invalid, and postponed indefinitely. (Doc 12)

To its credit, the Reagan administration moved quickly and decisively to confront Pinochet’s threat. In stark contrast to the procrastination of the Ford administration in taking steps to block the Letelier assassination, and the Carter administration’s weak response to the cover-up of that crime, Reagan officials forcefully attempted to insure the sanctity of the plebiscite. Unequivocal démarches were presented to a broad range of regime officials—in the foreign and interior ministries, the army, the Junta, and to Pinochet himself—warning authorities “not to take or permit steps meant to provide pretext for canceling, suspending or otherwise nullifying the plebiscite.” In their meetings with the Chileans, U.S. officials were authorized to use tough language: “I want to warn you that implementation of such a plan would seriously damage relations with the United States and utterly destroy Chile’s reputation in the world,” talking points read. “President Pinochet should also be informed that nothing could so permanently destroy his reputation in Chile and the world than for him to authorize or permit extreme violent and illicit steps which make a mockery of his solemn promise to conduct a free and fair plebiscite.”51

Behind the scenes, the CIA Station chief received instructions to strongly advise Chilean secret police officials against such action; U.S. military officers at SOUTHCOMM issued similar warnings to their contacts inside the Chilean military. Washington also asked the Thatcher government—a close friend of Pinochet’s—to privately pressure his regime. On October 3, the State Department raised that pressure at the noon press briefing by publicly expressing its concern that “the Chilean government has plans to cancel Wednesday’s presidential plebiscite or to nullify the results.”