|  |

Most casual history buffs have an idea that some of the best-known monarchs had long reigns that lasted for decades. And while there were people throughout human history that ruled for exceptionally long periods of time, most of them had only a few years of ruling to their name. In fact, some would barely last over a month. Let’s be a bit more concrete with this and use the medieval rulers we’ve mentioned thus far to illustrate the point. Bogdan II of Moldavia, the ally of the Draculs, ruled for a little over two years. Ladislaus V the Posthumous, although he is officially recognized as a ruler from his birth in 1440, didn’t actually independently take the throne until 1452, which means he ruled for around five years. And though Vladislav II technically ruled for nine years in total, his first reign (before Dracula seized the throne) was barely a year long. Vlad’s own father, Vlad II Dracul, had been a ruler of Wallachia for a grand total of ten years, which was split between two reigns. His predecessor, Alexander I Aldea, had only been a voivode for five years. The son of Despot Đurađ Branković, Lazar, ruled the despotate after his father for roughly two years and was followed by his cousin Stefan, who only ruled for fourteen months.

With so many examples of brief reigns, which seemed to be as frequent as local wars and uprisings, it’s no wonder that Vlad III’s longest and most notable period in power lasted a little over six years. When compared to some of the highest-regarded rulers of both Wallachia and Moldavia, such as Mircea I the Elder (ruled for a total of 29 years) and Stephen III of Moldavia, also known as Stephen the Great (ruled for an astounding 47 years), this particular rule of Vlad III seems almost insignificant in comparison. However, it was during these years that Vlad would establish himself as a powerful political player who wasn’t afraid of using any means necessary to achieve his goals and bring some stability to his land.

Stephen the Great of Moldavia, Gospel miniature, from the Humor Monastery, 1473[iv]

We don’t know the exact course of events that placed Vlad the Impaler back on the throne of Wallachia. However, we can safely manage to piece together what had happened in the few years before he did so. During his exile in Moldavia, Vlad began to repair his relations with the Hungarian Crown; more precisely, he was trying hard to get within the good graces of John Hunyadi.

This wasn’t an easy task at the time. The Hungarian kingdom was, effectively, just as hungry for Wallachian territory and influence as the Ottoman Empire. What made them almost a bigger threat than the Turks was their proximity; Wallachia and Hungary were literally neighboring states, while the whole of Bulgaria, Serbia, and what was left of the Eastern Roman Empire stood between Vlad’s land and the Ottomans. Moreover, thanks to the efforts of both the current political establishment at Buda as well as the rulers active during Vlad II’s time, the Hungarian nobles could lay legitimate claims over large swathes of territory in Wallachia. In addition, they would intermarry and produce offspring that would have hereditary rights over any of the lands. Hungary was effectively in the same position that the Habsburg Monarchy, i.e., the Austrians, would enjoy only a few centuries later.

In one sense, Vlad III was a bit cornered due to this situation with Hungary; outright refusing them would not be an option, as Hunyadi would not only refuse to offer help in case the Ottomans wanted to invade the voivode, but they could also very well attack Wallachia itself. However, Vlad’s decision to ally himself with the Hungarian kingdom more closely was actually a prudent political move. Most of his father’s Dănești-born rivals and claimants to the throne had outside help, and 90 percent of the time, it was the Hungarian king who provided it. Therefore, Vlad would simply use his enemies’ tactics against them, and he would do so preemptively.

Despite Vlad’s showing of goodwill toward Hunyadi, the Hungarian baron did not immediately (and openly) declare his support right away. After all, Vlad’s father was still fresh in the baron’s memory, and supporting his hot-blooded, shrewd son might have ended up backfiring on Hungary. There was a general aura of distrust, which was not unwarranted on Hunyadi’s part; immediately after taking the throne, Vlad would undertake actions that would do damage to the Hungarian economy and strain their relations even further.

However, Hunyadi himself also proceeded with some steps that would ensure Vlad’s mistrust in him. The baron had instructed the people of Brașov not to shelter Dracula on February 6th, 1452. However, soon after, the Wallachian voivode would return to this city with a task to defend it, a task proclaimed by none other than Hunyadi himself. While we know little of these events, we can safely say, judging by their proximity and outcomes, that the voivode and the baron made peace with one another between 1452 and early 1456.

The year was 1456, and depending on the source, it was either early spring or mid- to late summer when Vlad III Dracula invaded his homeland of Wallachia and reclaimed the throne from Vladislav II. Some sources even claim that the voivode killed the acting prince himself before declaring his sovereignty. Vlad achieved this victory in no small part thanks to the Hungarian forces sent by Hunyadi. And as a son of a former ruler, he had as much legitimate claim to the throne as his pretenders, some of whom were born bastards and all of whom tried to dethrone the voivode at one point or another. One of these pretenders was Dan III, while another was an unnamed priest mistakenly referred to as Vlad’s namesake brother, later known as Vlad the Monk.

Vlad’s coronation was not recorded, but based on how some of the later rulers of Wallachia were crowned, we can assume that most of the customs from the past coronations were used in these later ones, albeit with some changes. A typical coronation would involve the presence of all the court dignitaries, members of the clergy, local boyars, and regular folk. The church service itself was held in Church Slavonic, though most of the particularities of the coronation itself were derived from East Roman customs, as was the case with every Orthodox Balkan nation at the time. Typically, a ruler would receive a scepter, a sword, a gold crown with precious gems, the country’s standard, its coat of arms, a saber, and a lance. However, judging on the clothes that Vlad wore in the many contemporary descriptions of the voivode, some Ottoman customs must have crept their way into the event. After all, the Impaler’s regal clothing had some interesting Ottoman elements to it, including a caftan (a type of robe) made of velvet and silk that the sultans would wear, which was embroidered with gold filaments, buttons made out of precious stones, and fine sable lining.

Naturally, Vlad’s coronation and early rule were not without its problems. Just like any ruler at the time, Vlad III needed to have a council. Usually, around twelve people would serve as council members, tending to different duties regarding the court and the state. However, this number is not set in stone, and with scant data on Vlad’s reign, we can’t know for sure how many members his council(s) ultimately had, nor who they were. Based on what we do know, however, Vlad had the habit of disposing of any council member he deemed unworthy, often in brutal ways.

From 1456 to 1462, we have records of several key people during Vlad’s reign. One individual who, at first, hadn’t held any real office position during most of Vlad’s early childhood and adolescence was an elderly court scholar named Manea Udriște. He held the title of vornic, which would be the equivalent of a supreme judge. This was the same position he held during the reigns of several rulers, but in 1453, his own son Dragomir would succeed him, serving as a vornic to Vladislav II. Because of this circumstance, Vlad III saw Dragomir as a staunch adversary, so vornics disappeared from the political scene altogether during the Impaler’s second reign, coming back well after Vlad had been deposed and held captive by the Hungarians.

Of course, Manea was merely the first council member attested by historical documents to have served under the Impaler. Some of the other notable members include:

Vlad’s reign was infamous for the way he dealt with insubordinate or inefficient council members. Quite a few of the ones listed here disappeared from court documents altogether after less than a year since they were appointed (or at least attested to be in power). That’s because Vlad had the habit of executing any high-ranking boyar who didn’t perform his duties as prescribed. There were a few exceptions, however. The most notable was Cazan, a man who had been in the court’s service since the reign of Alexander Aldea in 1431. More impressive is the fact that he remained a court official until 1478, having been everything from a boyar to a chancellor and even a jupan.

One other key aspect of Vlad’s “revolving” council is the fact that some of its members had openly served his enemies, mainly the pretenders from the Dănești line. It would seem that Vlad was wise to execute them since those who were banished or managed to escape later came back to serve Vlad’s opponents. Duca is the best example of this phenomenon. Initially being Vladislav II’s councilor all the way back in 1451, he didn’t resurface until 1457, the first and only year he would serve under Vlad III. Historians speculate whether he was in league with the Saxons of Transylvania and the Hungarians, which would undoubtedly lead Vlad to believe that Duca was working toward deposing him in favor of a more docile pretender-ruler. Considering that Duca had served Vlad’s younger brother Radu for almost six years after Vlad’s own deposition, the voivode had been right to get rid of him as early as he did.

Somewhat paradoxically, even though Vlad had obvious xenophobic tendencies, which were almost always justified in some way and, lest we forget, not uncommon for contemporary monarchs, his court of “revolving” council members didn’t merely consist of Wallachians. We already saw from the official documents that both Greeks and even Saxons could end up in high positions at Dracula’s court. Laonikos Chalkokondyles, an Eastern Roman historian, wrote at length about the Balkans in his famed work The Histories, written in ten tomes. Regarding Dracula, Chalkokondyles mentions that the voivode had a court where no council member could trust each other due to how devious they all were. In the historian’s own words, Vlad would employ Hungarians, Serbs, Turks, and Tatars if they would serve his purposes. It’s also highly likely that a few Moldavians held some important positions, considering Vlad’s amicable relations with the rulers of this Romanian-speaking realm. It’s fascinating to learn that one of history’s most arguably chauvinistic rulers had such a diverse court, with their only common trait being how corrupt they were, a trait that ultimately besets any government body, even today.

As stated earlier, one of the major problems that the Wallachian court had to deal with was the shifty nature of the boyars and the rowdiness of the commoners. Vlad’s desire to have full control over who got to sit on his council, as well as his swiftness in removing those that would undermine him, resulted in a country that was a bit more uniform than before. Granted, he wouldn’t always reward loyalty on the part of his advisors. Codrea, for example, was staunchly loyal to Vlad III, but that didn’t stop the voivode from executing him in 1459.

Vlad’s Wallachia was a small, largely rural country. Based on certain estimates and educated guesses, it must have had, at most, 400,000 inhabitants. Of those, more than 90 percent lived in villages. There were only seventeen major market cities, of which three would serve as court capitals. The first was Câmpulung, and it would remain a capital from at least 1300 to 1330, which was when it was replaced by Curtea de Argeș. Târgoviște, Vlad III’s capital, would rise to prominence in 1408.

Some of the other major cities in Wallachia included:

Interestingly, no city in Wallachia had strongholds like other cities in the medieval Balkans. The few that did would usually be held by the Hungarians or the Turks. Instead, the local populace would choose to hide in forests or monasteries if there was a major war or a disaster. The cities themselves were poorly fortified, with either flimsy brick or wood enclosures around them. To the native Wallachians, that lack of fortification was a blessing in disguise since most fortified cities were constantly fought over by different regional powers; thus, living inside such a city would see a lot more deaths and hold a lot more danger.

Coming back to the population of Wallachia in the Middle Ages, the estimated figures show just how brutal and efficient Dracula’s regime had been. When the 1470s came, the same area that was ruled by the Impaler had, at the very least, 60,000 people less than during his time. Of course, wars and uprisings account for some of those losses, but even if we take that into account, the number of people who died during Dracula’s reign is staggering.

Within that population, Vlad III actually did have people who were willing to lay down their lives for him, and the majority of them constituted his army. The voivode’s troops consisted of two major regiments. The first was the so-called “small army,” made up of sons from lesser nobles, certain boyars, and the landowning free folk known as curteni (the term being a plural form of curtean). There were no more than 10,000 people that made up the small army, which made it merely a third of the larger “great army.” This massive regiment consisted mostly of commoners who were old enough to bear arms, and the absolute majority were men.

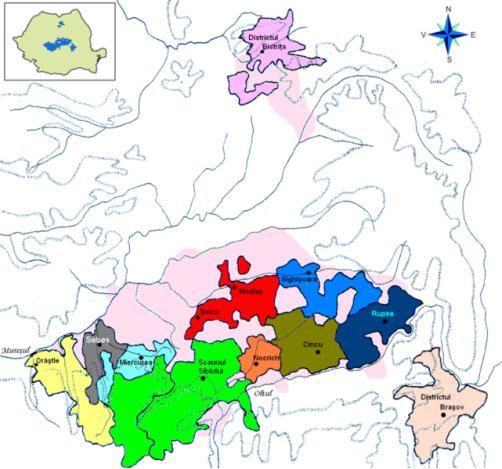

Medieval seats of the Saxons in Transylvania during the reign of Vlad the Impaler[v]

The Impaler’s rise to power bore new challenges and issues. As a voivode, he had to establish or reestablish foreign relations with the surrounding monarchies, including heavyweights such as Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. In terms of the former, Vlad was, at the moment, somewhat safe. John Hunyadi had finally provided open support to him, though it wouldn’t last for long, as Hunyadi would soon die in August 1456. However, Hunyadi’s word was an important political advantage to Vlad, considering how much influence the baron had had at the court in Buda. With his early death, however, nearly all of the state affairs of Hungary were squarely in the hands of the king, the young Ladislaus V the Posthumous. Vlad immediately set about to swear loyalty to the king, which can be attested from several treaty documents that the voivode signed with the Saxons of both Brașov and Sibiu. These treaties obliged Vlad to defend the Transylvanian Saxons from Turkish invasions and allow the Saxon merchants to move freely without having to pay taxes (though this last privilege was not afforded to the people at Sibiu); in return, the Transylvanians and Hungarians had to provide shelter to the voivode should he be attacked by either an external force or an internal traitor (and with the pretenders to the Wallachian throne emerging on an almost yearly basis, this wasn’t an unreasonable request on Vlad’s part). Naturally, the Impaler did not uphold his end of the agreement, considering that the Turks were already raiding Transylvania mere days after the signing. It’s no wonder, then, that the burghers of Brașov, Sibiu, and Amlaș openly hosted two different pretenders to the throne, Dan and Vlad, respectively, after Hunyadi’s eldest son Ladislaus wrote a letter about the Impaler’s supposed crimes. After reading the letters, one might get the impression that Ladislaus was purposefully vague in his assessment of the Wallachian voivode, and one would be absolutely right. In the mind of Hunyadi’s son, as well as the majority of Hungarian and Saxon nobility in major Transylvanian cities, Vlad was expendable, and they merely needed a good excuse to replace him with someone more submissive.

Of course, Vlad did not earn this treatment out of thin air. At some point between late 1456 and early 1457, the voivode had issued the production of new Wallachian coins. One such coin was the silver ban, which was similar to the golden ducats of Vladislav II insofar as it was made out of pure metal and weighed roughly 0.40 grams. Minting coins with their own heraldry and value might seem like a trivial matter, but we need to take into consideration that Hungary and Wallachia had been in a monetary union since 1424. In other words, the Wallachians were under obligation to use Hungarian coins, which made them, in no small part, financially reliant on the Buda court. With their own mint, the Wallachians gained a new level of autonomy, which would harm Hungarian interests. Moreover, the Hungarian coins were dangerously devalued at this time, as opposed to the new ones issued by Vlad III.

The other potential reason why Vlad was deemed an enemy by Ladislaus Hunyadi and the Transylvanians was the fact that he wanted to reclaim old territories that were no longer under direct Wallachian rule. Vlad would launch concentrated attacks on Brașov, Sibiu, and Beckendorf, a town that supposedly housed Dan III, one of the pretenders to the throne during Dracula’s reign.

What’s more interesting is that Dracula’s sieges of Brașov and Sibiu were not entirely for his own benefit. Namely, despite Ladislaus’s treatment of him, the voivode remained loyal to the Hunyadis, which would prove to be instrumental in the events to follow. After John Hunyadi’s death in August 1456, his older son, along with his widow Elizabeth and his surviving brother-in-law Michael Szilágyi, created a rift in Hungarian court politics. Hunyadi’s death came less than three weeks after the famous Siege of Belgrade, where he successfully crushed the Ottoman forces of Sultan Mehmed II, the same man who had crushed Constantinople and ended the Eastern Roman Empire a little over three years before the siege. One of the carryover disputes that had remained after Hunyadi’s death was his rivalry with Ulrich of Celje; Ulrich would eventually be killed by Ladislaus Hunyadi on November 9th of the same year. Considering Ulrich’s position as one of King Ladislaus V’s regents, the young monarch had to swear to the House of Hunyadi that he would not pursue vengeance. However, his loyal barons, among whom were powerful figures such as Ladislaus Garai, Ladislaus Pálóci, and Nicholas Újlaki, strongly opposed this decision, and the country was flung into a de facto civil war. Garai and Pálóci were high-ranking court officials, with the former being a palatine (something akin to a viceroy or a regent) and the latter being a judge royal, which was the rank directly beneath the palatine. Újlaki, on the other hand, was a voivode of Transylvania, a position he shared with the now-late John Hunyadi, so his involvement in this matter would directly influence matters in Wallachia as well.

The aforementioned barons were merely three of the many supporters of Ladislaus the Posthumous. However, there was a growing sentiment that the House of Hunyadi should take the throne. The idea materialized when Ladislaus V imprisoned both Ladislaus Hunyadi and his younger brother Matthias, having the older brother executed in March of 1457. In retaliation, Elizabeth and Michael Szilágyi would form the so-called Szilágyi – Hunyadi Liga (League), a movement openly supporting the dethronement of Ladislaus and the elevation of young Matthias to the rank of king. Their troops began to raid the Hungarian regions east of the river Tisza, forcing the young king to flee to Vienna and take Matthias with him. While there, Ladislaus the Posthumous died unexpectedly on November 23rd, 1457. He had no issue, so a brief interregnum ensued. In order to avoid a proper civil war and to appease all parties, the Hungarian Diet (equivalent to a modern parliament) crowned Matthias king on January 24th, 1458. He married Anna, the daughter of Ladislaus Garai, who also happened to be the widow of Matthias’s late older brother, sealing the treaty between the loyalists and the Liga. In addition, Michael Szilágyi became the regent of the new young king. Interestingly, though Nicholas Újlaki had been one of the biggest opponents of the Hunyadis, he would end up being one of King Matthias’s most trusted supporters in later years, earning several important titles. Most of these titles were related to the territories in the West Balkans (he was dubbed the king of Bosnia, which had already been an Ottoman territory at the time, as well as the ban, a high-ranking noble akin to a prince, of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia, and, more importantly, a perpetual count of Teočak, an area in Bosnia near today’s city of Tuzla). In other words, Újlaki had next to nothing to do with Transylvania long after Vlad III’s deposition.

Michael Szilágyi was a key figure in Vlad’s reign during 1457. As a loyal Hunyadi supporter, he launched a few campaigns against the Szeklers and the Saxons of Transylvania, focusing on Sibiu and Brașov. He did this in early 1457, around the same time that Vlad III issued his ultimatums to these cities. The Szilágyis and Vlad III took a decisive victory, forcing the local Saxon burghers and the people loyal to Ladislaus V to sign a treaty favoring the winning side. Vlad gained much from this treaty: the pretender Dan was expelled from the area, and the locals were under obligation to refuse any further aid to him. In addition, Vlad reopened trade with their merchants, which would see a boost in the local economy. Of course, the biggest win was the fact that Wallachian merchants finally had full freedom and safety to trade on Transylvanian soil, a feat that next to no predecessor of Vlad’s had managed to achieve despite years of failed attempts. In short, the Hungarian power struggle was the perfect opportunity for the Impaler to kill a few birds with one stone: first, to reclaim territories that he saw as his ancestral home (intriguingly, the treaty itself was signed in his native Sighișoara); next, to provide an easy economic boon for his country’s merchants with minimal losses on his part; then, to secure a powerful outside ally in the form of Michael Szilágyi and to establish himself as a relevant political factor in the region; and finally, to establish himself as a dominant force in his native Wallachia and as a deterrent against any potential claimants to his throne. Vlad had been in power less than a year, and he had already accomplished this much simply by making prudent, strategic choices.

However, Vlad’s good fortune would not last long. King Matthias would dismiss Garai as his palatine and later persuade Szilágyi to renounce his title as regent. In June of 1458, Szilágyi was appointed as the count of the district of Bistrița, one of several major seats of the Transylvanian Saxons. Though Szilágyi himself didn’t resign as regent until the next year, young Matthias was effectively the sole ruler of the kingdom, and the two were immediately at odds. Because of the raven that was featured prominently on the House of Hunyadi’s coat of arms, Matthias bore the nickname Corvinus, a sobriquet his issue would inherit.

Unlike some of his predecessors, Corvinus favored the Saxons over the Wallachians, hence why he didn’t provide immediate support to Vlad III. In fact, while Szilágyi was plotting against the young king (and was arrested for his actions in Belgrade by the end of the year), Corvinus dispatched an envoy, the Polish noble known as the Benedict of Boythor, to Wallachia to have a delicate discussion with the voivode. According to legend (which we will cover in a later chapter), the ambassador didn’t exactly feel welcome at the court in Târgoviște. In fact, he was downright terrified of the Wallachian ruler, and to be fair, if he hadn’t approached the matter prudently, he would have most likely been killed on the spot. Benedict’s mission was to convince Vlad III to stabilize his relations with the Transylvanian Saxons, who, in turn, would admit to wronging the voivode and his people in the past. Because of his history with the Saxons, Dracula wasn’t too pleased with this task set before him by the young king. In fact, he would do the exact opposite in the coming months—not only would he issue a new silver ducat and have it minted in the new capital of București, but he would reinstate the trading bans and high taxes to all Saxon merchants from Sibiu and Brașov. To be precise, he limited their capacities to three cities in total: Câmpulung, Târgșor, and Târgoviște. The Wallachians were, once again, exempt from these new laws, clearly letting the Saxons know where they were in the voivode’s pecking order.

Vlad III was also asked to join the possible crusade against the Turks. The reasons for these were aplenty: Serbia, a notably weak country at that point, was going through political turmoil after the death of Despot Lazar Branković. His brother, known as Stephen the Blind, and Lazar’s widow, Helena Palaiologina, held power and wanted to pledge their allegiance to the Hungarian court. However, an army commander known as Michael Angelović wanted to become a vassal of the Ottomans, largely due to the fact that his own brother, Mahmud Pasha, was the grand vizier and the sultan’s main advisor at the time. Lazar’s successors arrested Angelović, which prompted Sultan Mehmed II to send Mahmud Pasha with an army to Serbia and finish the conquest. At that point, only the city of Semendria (modern-day Smederevo) managed to withstand the Turkish advances.

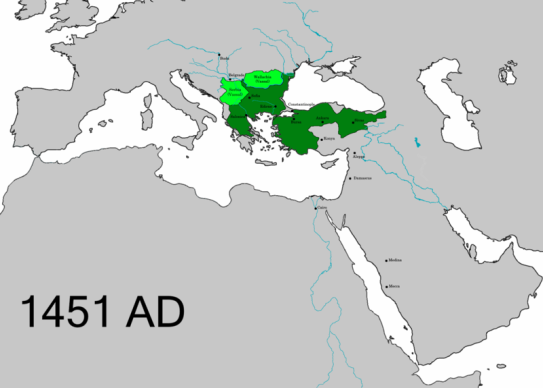

The reason why Serbia’s inevitable downfall was important to both King Matthias Corvinus and Vlad III is rather pragmatic. The remnants of the Serbian Despotate was literally the only thing that stood in the way between the Ottomans on one side and Wallachia and Hungary on the other. Without that buffer, both countries were exposed to potential lootings, attacks, incursions, and other dangers. Luckily, Mahmud Pasha didn’t reach Semendria properly; according to some eyewitness accounts, which were written by an anonymous contemporary of these events, the Turkish commander entered Wallachia, claimed a fortress (more than likely the one at Turnu Severin, though this is yet to be confirmed), and, after attempting to cross the Danube with his soldiers and his prisoners, was brutally attacked by Dracula and his army of 5,000 people, which consisted of both Wallachians and Hungarians. If the historical account is to be believed, out of 18,000 Ottoman soldiers, less than 8,000 were able to retreat. The rest were either killed in battle or drowned in the river. The Serbian question would, of course, not be solved properly, as Matthias had agreed in a council with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III to marry Despot Lazar’s daughter to the current king of Bosnia, which was another failing state at the time. In 1459, Mehmed II would finally annex what was left of Serbia, leaving Hungary, Transylvania, and Wallachia exposed to further attacks.

Matthias Corvinus, due to Vlad’s actions against the Saxons and the Szeklers, began to provide support to the pretenders to the Wallachian throne, not unlike how his father had handled things back in the day. Two of these pretenders were known as Basarab II and Dan III, the latter of which was presumably killed by Vlad himself in a particularly gruesome way. In addition to these actions, the young king had also allowed these pretenders to seek shelter among the Transylvanian Saxons, but more importantly, he prohibited any merchants from Brașov to trade arms with the Wallachians.

This animosity between the rulers would last at least up until 1460. However, as the years went by, the two men grew to understand one another, and their relations became somewhat normalized. In fact, in 1461, Matthias proposed that the Wallachian voivode marry a woman from his family, the noblewoman (and Vlad’s future second wife) Jusztina Szilágyi. This bit of news greatly unnerved Sultan Mehmed II, who rightfully saw it as a way for Vlad to strengthen his alliances with the other Christian nations and possibly work on a way to fight off the Turks. In the final years of Vlad’s second reign, this would spiral into war and deliver heavy losses to both sides.

Relief of King Matthias Corvinus, from Beatrice of Naples and Matthias Corvinus, author unknown, circa 1485–1490 (this piece is a later copy from the 19th century)[vi]

Initially, though not willingly, Vlad had been an ally to the Ottomans. For instance, he would not openly attack them during the early months of his reign, opting to stay, more or less, neutral with strengthening only some of the key relations with the Hungarians and the Moldavians. Interestingly, unlike most vassal states during the reigns of Murad II and Mehmed II, Wallachia had remained largely autonomous. Vlad, of course, had to pay an annual tribute to the Turks to prevent the wrath of the sultan’s army. However, there were a few key elements that made him a more independent ruler than his contemporaries. For instance, none of Vlad’s immediate family members were prisoners of the sultan other than his brother Radu. However, by this point, Radu had been staying at the Ottoman court willingly, having become somewhat of a favorite to the sultans. In fact, it might have even been Radu’s insistence that brought Vlad III to the throne in the first place, which is made all the more plausible considering that the Impaler hadn’t made any attacks on the Turks in his early reign.

Another important element to Wallachia’s autonomy in 1456 was the fact that Vlad, even during the final days of his reign, never sent any young boys as a tribute. Sources from the time attest that he had to send at least 500 young boys to the sultan each year, but based on Vlad’s personal correspondence with the rulers at the time (including his letter to King Matthias Corvinus), there didn’t seem to be any mention of this demand on the side of the Ottomans. A reader might conclude that Vlad simply lied by omission that he didn’t have to send any young boys as a tribute, but this is highly unlikely. After all, he clearly stated in his letters what he believed the Turks were planning and what dangers they posed to his country and countrymen. As someone seeking help against an aggressor, it would be illogical to leave out such a significant method of subjugation as the Devshirme.

We can find the third and final element that proves Vlad hadn’t been a completely submissive vassal of the Ottomans within the legal documents from his time. While he was in power, Vlad had refused the Ottomans free passage through Wallachia for the purposes of raiding the Transylvanians. They were also not allowed to settle in Wallachia permanently, buy or own land, construct mosques, or attain any proper political power. In addition, Orthodox Christianity was freely practiced, and the prince, if not by means of primogeniture, could only be elected by the boyars and the clergy, not by the Ottomans directly.

Vlad’s shaky relations with nearly everyone would soon bear bitter fruit. When Mehmed II learned of the voivode’s planned marriage with the cousin of the Hungarian king in early 1462, he sent an envoy to try to convince Vlad to visit the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman’s medieval court) and discuss future endeavors. The servant whom the sultan dispatched to finish this task was a Greek secretary known as Thomas Katabolenos, a skilled diplomat recommended by the ecumenical Christian patriarch himself. After the fall of Constantinople, the Greeks, who still considered themselves as Eastern Romans, were under the sultan’s rule, but he did not exactly rule over them directly; instead, the patriarch and the Church took over most of the governing duties as proxies. Considering the status of the Eastern Roman Orthodox Church as ecumenical, i.e., the one above all others, the Orthodox Churches of both Wallachia and Moldavia were its direct underlings. Therefore, Mehmed II’s move was quite prudent. A diplomat with the knowledge of Christian affairs would be able to convince Vlad more easily to visit the sultan than any Muslim diplomat would.

But Vlad was anything but ignorant of what this invitation meant. His own father had made the mistake of appearing at the sultan’s court before, and the whole family ended up in disarray after that, to put it mildly. Therefore, the Impaler asked the sultan to send a local bey (a title meaning “chieftain of an area of land”) to “guard the frontier and keep the country safe”; the reasoning Vlad used was, indeed, quite sound and surprisingly accurate, as he claimed that the country, which would be left to the local boyars, would fall apart since nobody was faithful to him. With that in mind, Mehmed II sent Hamza Bey, the governor of Nicopolis, to watch over the Danube River.

Cunningly, Dracula sent a letter to King Matthias Corvinus, warning him of the dangers that the Turks posed and, almost predictably, stating that his venture into Constantinople would mean his death and that Hamza Bey was more than willing to drag Dracula to the Ottoman’s new capital, by force if necessary. So, Dracula acted quickly, capturing both Hamza Bey and Thomas Katabolenos and impaling them soon after. Around forty of their men were also impaled and mutilated, with their corpses lining the walls of Târgoviște.

Of course, that was merely the precursor to what we call Dracula’s Danubian campaign. Not long after he had the two servants of the sultan dispatched, Vlad took his army across the frozen Danube and divided the men up into several squads. His plan was to cover all of the frontier lands next to the great river, from Chilia in the southeast to Rahova in the northwest, near the mouth of the Jiu River. It was a massive 800-kilometer (almost 500-mile) swath of land to cover, and they had to do this in the midst of a devastating winter no less. But Vlad III did far more than simply succeed in his intended mission. In fact, he utterly crushed nearly everything next to the Danube River that wasn’t Wallachian. In the process, he recaptured the important fortress of Giurgiu, reportedly ordering the locals to open the gates in fluent Turkish before having his men flood it and murder anything that moved.

Both Turks and local Bulgarians died in the constant raids, killed either on land or while on the river transporting goods. No women or children were spared during this horrific raid, and all of the people that didn’t die by the sword would succumb to the flames of one of the hundreds of fires. By his own estimate, which might be exaggerated but is fascinating nonetheless, the voivode claims to have killed a grand total of 22,883 people. And, in his own words, those were just the ones whose heads were accounted for. He didn’t count any of the people burned alive or killed in such a way that you couldn’t separate the head from the body.

Aside from this mass murder, tantamount to genocide if not for the diverse nationalities that died under Wallachian swords, Vlad also ordered the destruction of material goods, transport vehicles like carts and rafts, houses, keeps, churches, and what few forts there were on the Danube on the Bulgarian side. His plan was to completely cripple the locals from funding and supplying the Ottoman troops in case the sultan felt like invading the voivode. But more importantly, Vlad wanted to show the Turks that he meant business, that even the best-prepared armies of the sultan could do no damage to his own warriors, and that he was both capable and willing to murder thousands of civilians to prove his point.

In a lengthy letter he sent to King Matthias Corvinus, Vlad lists off all of the cities, towns, villages, and forts that ended up burned, sacked, or damaged after he laid his siege. There is no real sympathy in the voivode’s voice for all of the innocents that died; he merely lists them off and brushes them aside in the very next sentence. What’s more disturbing, however, is the duplicity of some of Vlad’s statements. He claims to have done what he did for the preservation of Christianity, the Catholic faith, and the crown of the Hungarian king, but every single one of those statements is patently hypocritical. Based on every source we have, Vlad only converted to Catholicism during his imprisonment, which took place sometime before his death. Up until that point, he was more than likely an Orthodox ruler, even if he wasn’t practicing and despite his heinous acts while at court. Next, we know that he rarely put stock in Christianity as a moral goal, considering that he had refused to join a few potential crusades. Moreover, the Hungarian crown didn’t exactly mean much to him, other than the fact that it was placed on the head of a powerful political ally (whose position at court was, at best, as shaky as his own in Wallachia). And lastly, Vlad had committed most of these atrocities against innocent Christian men and women of Bulgaria. No self-described fighter for Christianity would even think to condone the murder of civilians, let alone in the way that Vlad had done it.

With the letter sent, it was Corvinus’s time to act. Thanks to his efforts, this same letter reached other European rulers at the time, even finding its way to northern Italy. Though Matthias might have felt sympathetic to Vlad’s cause (or at least saw an opportunity to crush the Ottomans), his royal budget and the state of his court would not allow him to waste any money on an anti-Turk campaign. He lobbied hard with various Italian nobles and the clergy for monetary assistance in this potential crusade, but it ultimately came to nothing. Alone, Corvinus could simply not risk a war with the sultan.

The defeat of the Ottomans was so crushing and devastating that it’s not a stretch to call it their biggest defeat (up to that point) since Mehmed II came to power. Naturally, the Porte had to retaliate, so the sultan amassed what was possibly the biggest army since the Siege of Constantinople, which had taken place less than a decade prior. Two of the main regiments of his army consisted of ground troops, with himself at the helm. They headed directly for Dracula’s old capital of Târgoviște. The fleet, however, was in Brăila, a port city close to another important inhabited area, the contested city of Chilia. Stephen the Great of Moldavia had always been an ally to the Wallachian voivode, but Chilia never stopped being a hot-button issue, one that the Moldavian ruler sought to fix. Brăila itself would be burned to the ground, but Chilia would not fall into Ottoman hands, nor would it go back to Prince Stephen that year. Though the Turks themselves saw this port as extremely important and placed great emphasis on capturing it, they wouldn’t seize control of it until 1484.

Vlad had seen the sizable army of Mehmed II. On June 4th, 1462, the army crossed the Danube at Nicopolis (modern Nikopol in Bulgaria) and moved steadily toward Târgoviște. Once again showing his cunning nature, Vlad employed a scorched-earth policy; every time he retreated, his army would burn the crops and destroy all the dwellings, leaving nothing but ash to the conquerors. The hot summer sun greatly helped Vlad in this endeavor. By the end of the campaign, the Turkish troops had suffered great heat exhaustion and strokes, with the losses on their side being significantly higher than those on the Wallachian side. However, Vlad’s real moment of triumph, as well as potentially his biggest failure, would come on the night between June 17th and June 18th.

Several different historical accounts at the time spoke of this attack, and while there are some significant variations in terms of details, the basic course of events is the same. Upon reaching Târgoviște but before entering it, the Ottomans set up a base camp. Vlad saw this as a great opportunity for a task that was nowhere near easy but which could change the course of the war significantly. Taking anywhere between 7,000 and 10,000 men, the voivode divided them into two groups and attacked the camp at night, when the Ottomans least suspected it. His main goal was to kill Mehmed II and his chief viziers. The murders of these individuals would then act as a catalyst for the Turkish armies to fall into disarray. Had Vlad succeeded, there would have been a dynastic battle at the Porte, allowing the Christian nations of the Balkans to breathe a sigh of relief for a short while and reorganize their efforts. Sadly, Vlad did not harm the sultan (though, according to some sources, the voivode’s army did wound Mehmed, albeit not fatally) and had to retreat into the thick Wallachian woodland. The Ottomans were, reportedly, terrified beyond belief, and after the confusion had settled, they somehow managed to capture a number of Wallachian soldiers and decapitate them in retaliation.

Vlad’s final proper act of defiance was caused by his absence from Târgoviște when the Ottomans reached it by the end of June. Sources claim that the Muslim army had entered a deserted town, which was littered with impaled corpses of all ages, both male and female, and all nationalities. They even recognized some of the court dignitaries from Constantinople that had been dispatched earlier that year. The sultan himself stated that he could not deprive Wallachia of such a cruel yet competent ruler, so he left the capital, with his men dumbfounded and confused as to what had just happened.

Map of the Ottoman Empire during the second reign of Mehmed II the Conqueror;

Wallachia and Serbia shown in light-green[vii]

Upon his retreat, Mehmed began his movement toward Chilia, which was now under attack from Stephen the Great. Some documents from this time imply that the Moldavian prince had begun raiding Vlad’s borderlands earlier that year, even as early as before Mehmed’s campaign. Considering the friendship and alliance between the two rulers (both before and after 1462), this action on the part of Stephen might seem confusing at first until we talk more about the city of Chilia.

As an important port, it had been in the hands of the Wallachians (or rather the Hungarians through a Wallachian proxy) since 1448. Stephen saw an opportunity to reclaim it in the summer of 1462 when it was garrisoned by a mix of both Hungarian and Wallachian troops. But in order to do that, he needed to find the right moment, so he agitated Vlad in order to split his attention between the Moldavian troops and the approaching Turks. Once the Turks had returned from the Wallachian lands, the Moldavian prince laid siege to the city.

It’s not impossible to think that Stephen managed to convince the Ottomans that they were allies due to his actions against Vlad, and even contemporary historians like Chalkokondyles and Tursun Bey, Mehmed’s own secretary, claim that Stephen had been loyal to the sultan. However, the siege of this city was a failure for the attackers. Not only would the Ottomans suffer yet another defeat at the hands of the Wallachians, but Stephen himself was also wounded in his left ankle, an injury that never properly healed and which was the primary cause for the gangrene infection that killed the Moldavian prince in 1504.

Vlad himself had also started moving toward Chilia, leaving roughly 6,000 soldiers to defend the realm from the Ottomans, which they failed to do. Not long after, another pretender to the throne appeared in the Bărăgan Plain, a vast area extremely close to Târgoviște and a fertile land that housed some of Wallachia’s biggest cities at the time. During his campaign, Mehmed II had taken with him a familiar servant who was his favorite in every way. Upon arriving in Wallachia, Radu the Handsome began to campaign hard in order to get as many boyars to accept him as the ruler and avoid more Ottoman attacks. Within months, the two brothers would clash in battle several times, and nearly all of those battles were won by Vlad. Nevertheless, more and more boyars began defecting to Radu, and the Ottoman forces did not stop advancing, leaving Vlad with barely any allies in his crucial moments.

Historians from mid-20th century Romania almost exclusively claimed that Vlad had done nothing but win against the Ottomans and that his exclusion from the throne was solely due to the traitors among the boyars. Of course, a more nuanced view suggests that there were a myriad of reasons. While it is absolutely true that there were boyars defecting to Radu, the number of potential traitors had greatly decreased while Vlad was in power, thanks in no small part to his brutal way of dealing with those who opposed him.

Stephen the Great’s armies were now an enemy. The Ottomans did not slow their march. Towns and cities burned all over. Radu had become the voice of a significant number of traitorous boyars. All of those elements together were slowly but surely leading to Vlad’s downfall in late 1462. An opportunist as always, Vlad retreated to the Carpathian Mountains, effectively dethroning himself and giving Radu all of the power. The voivode’s plan was to meet up with Matthias Corvinus and, with the help of the Hungarians, reestablish his rule. But the situation kept getting grimmer by the day. Albert of Istenmező, a Szekler count at the time, declared that the Transylvanian Saxons were going to shift their allegiance to Radu and recognize him as the new voivode. In addition, the younger Dracul also struck up a deal with the Saxons of Brașov, promising them financial and economic benefits in exchange for their loyalty.

The young Hungarian king had, on the surface level, taken Vlad’s pleas for help into consideration, seeing as he was in Transylvania in November 1462. Stephen the Great’s stance on waging war against the Turks did not change from earlier that year, though—he simply did not have the manpower, nor the money, to finance the endeavor. The two rulers negotiated for weeks before the meeting, it would seem, but judging by what happened (and the documents that surfaced later), we can safely assume that Corvinus had absolutely zero intention of assisting Vlad. He ordered his mercenary commander, a Czech strategist called John Jiskra of Brandýs, to capture Vlad, which Jiskra did near the town of Rucăr. Some accounts state that it was Vlad’s own companions who rebelled and captured him at the fortress of Piatra Craiului and then handed him over to Jiskra. Other sources state that Vlad was captured on his way back to Wallachia after the negotiations with the Hungarian king fell through.

Historians do not know the reason behind Corvinus’s capture of Vlad in 1462. Even Corvinus’s court historian, an Italian poet and famed humanist Antonio Bonfini, states that he did not know why the king captured the voivode. There are three important documents that relate directly to this event, and they were sent to both Pope Pious II in Rome and to the Venetians, who had actually sent some money to finance a potential crusade against the Ottomans during Vlad’s military exploits. These documents are the supposed letters that Vlad himself had written. One of them was meant for Sultan Mehmed II, the other for his grand vizier Mahmud Pasha, and the third for Stephen the Great of Moldavia. Apparently, they all contain the same basic premise, with the voivode promising to invade Hungary if the Turks helped him stay in power.

After analyzing these letters, we can safely say that they are forgeries. Dating them reveals that they were most likely written during Vlad’s captivity in the Hungarian town of Visegrád. More importantly, by analyzing the style and sentence structure, we can definitely conclude that none of Vlad’s character, which emanates from letters that actually came from him, is present. These letters were, therefore, made to justify Vlad’s imprisonment to King Matthias’s Catholic allies from across the Adriatic, though we may never know why exactly the voivode was captured in the first place.