Many groups of people settled in the British Isles, bringing their gods and goddesses with them. With the passage of time, these old deities were forgotten or were turned into fairy stories. Some of them even became saints. An example is St. Brigid, who was originally a goddess of inspiration and poetry. The line between the old and new religions was often blurred. St. Patrick used a charm to turn his followers into deer to escape their enemies. St. Columba, who surely started out life as a druid, persuaded the Loch Ness Monster to stop eating people. Ravens, after being scolded by St. Cuthbert for vandalizing his roof, made amends by bringing the saint a slab of lard to oil his boots.

How these early missionaries loved to travel! They wandered from village to village, camping out, getting free food, and avoiding nine-to-five jobs. They loved being alone, finding the most remote islands on which to build huts. St. Cuthbert had to be dragged from his to become the abbot of Lindisfarne and was most annoyed about it.

Northern Europe during the fifth to eleventh centuries was a mixture of religions. Worshippers of Odin, druids, wise women, Christians, and people of faiths we can only guess at lived side by side. We don’t know what the Picts worshipped. We have only their strange and beautiful carvings—a crescent crossed by a broken arrow, a beast with curled feet and a mouth like a dolphin. I have given them the Forest Lord (also called the Green Man), the Man in the Moon, and the Wild Huntsman as gods. But no one really knows. Nor does anyone know where such beings as the will-o’-the-wisps, hobgoblins, the Lady of the Lake, mermaids, and yarthkins came from. I think they are old gods who lingered on into a twilight with the elves.

As for the elves, the belief that they were half-fallen angels is found in early Christian writings. It was certainly an idea the famous author J. R. R. Tolkien knew about, although he chose not to use it.

St. Filian’s name is also spelled “Fillian” and “Fillan.” There was a St. Fillan’s Well in Scotland, where people suffering from insanity were thrown from a high rock into its water. You could call this an early form of shock therapy. In the eighteenth century a minister had the well filled in to stop the practice. In 2005 a construction company called Genesis Properties wanted to remove a large stone near St. Fillan’s to make room for houses. Angry locals refused to let them touch the stone because they said elves were living underneath it. Genesis backed down.

The fortress of Din Guardi lies near the city of Bamburgh (Bebba’s Town) and across the water from Lindisfarne (the Holy Isle). It is very old, possibly going back to Neolithic times, and was built and destroyed several times. It is now called Bamburgh Castle. It is supposed to be the site of Joyous Garde, Lancelot’s palace.

Many interesting things have been discovered buried beneath it, but the most fascinating was a sword. It was probably the finest sword of its time, and even today, scientists aren’t sure how it was made. There is nothing like it in existence. The archaeologist who discovered it hid it in his house for forty years, apparently to enjoy its possession in secret. When the man died, the sword was thrown away, but fortunately, his students got there before the garbage collectors.

Of course, this is the sword Anredden, made by the Lady of the Lake. Only she knows how it was done.

Northmen did not have a good way to record their history. They carved symbols into rock, and through the years some of these evolved into an alphabet. But there is only so much you can say if you have to depend on rocks instead of paper. Most stories were turned into poetry and memorized.

The alphabet symbols were called “runes.” Some of these were associated with gods and invoked their powers. Two or more could be combined to make a talisman called a galdrastafir.

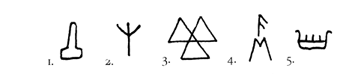

The symbols carved for Thorgil and Heinrich are as follows:

1. Thor’s hammer (mjöllnir)

2. The rune of protection; also the symbol for Yggdrassil (algir)

These stand for Thorgil. In the middle (3) are the “knots of death” (valknut), also known as the “mind-fetter” Odin casts on those warriors he wishes to claim for his own. These are followed by:

4. Odin’s rune (oss) above the rune for horse (ior); this indicates Odin’s eight-legged steed, Sleipnir

5. A spirit ship

When algir (2), the rune of protection, is repeated in the talisman below, it becomes many times more powerful. This is what is carved on the amulet Thorgil wears around her neck.

Pictish symbols are carved on many stones in Scotland, as well as a few stones in southern France. They are so distinctive and complex, it is certain they had an important meaning. Unfortunately almost no information about Pictish culture has survived. Their language has vanished. Their history is clouded in myth. Their gods remain mysterious.

Their art, however, endures in the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Book of Kells, and many other works. It is clear they were done by master artists. Their animals are drawn with great realism and skill. Thus it is a surprise to find the Pictish beast to be completely unidentifiable. (It is the creature with the curled tail and topknot.) People have called it a dolphin, a horse, and even an elephant. It is a common symbol, and there are tales about it. One (which occurs in the book) describes it as the size of a cucumber when born, and quickly growing to enormous size.

The broken arrow is a common motif in the carvings, particularly the broken arrow crossing the crescent moon. This has been interpreted as a death symbol for a man, while the comb and mirror are death symbols for a woman. In The Land of the Silver Apples, the broken arrow and moon are tattooed on the chest of Brother Aiden, indicating that he is marked for sacrifice. These moons and arrows are often enlaced with vines. I have used them in the book as markers for the three main gods of the Picts: the Man in the Moon, the Forest Lord (or Green Man), and the Wild Huntsman. This is entirely my idea—no one knows who the gods of the Picts were—but the three beings occur in ancient lore all over northern Europe.

Most interestingly, the distinctive comb (which looks almost like a garden gate) and mirror occur in carvings of mermaids. I don’t think this is an accident. It is quite possible that the mermaid was a Pictish sea goddess and that these symbols refer to her.

The meanings of all the symbols are guesswork, but here are some possibilities from The Pictish Guide by Elizabeth Sutherland, printed in Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997:

A solar disc held by a human.

The broken arrow crossing the crescent moon indicates the death of a man.

The mirror (left) and comb (right) indicate the death of a woman.

The three ovals connected by a chain may be a bracelet.

The snake crossed by the broken arrow (also called a “Z rod”) may mean renewal and immortality.

The curved, flowerlike design may be a flower or a horse’s harness.

The arc may be a rainbow, which was considered a bridge to the other world. This is sometimes shown with the broken arrow.

The double disc crossed by the broken arrow is supposed to indicate the duality of the sun, which lights this world by day and the otherworld by night.

This curved form is probably only a decoration.

The rectangle may be a container for valuables.

The notched rectangle crossed by the broken arrow may be a chariot or a fortress.

Our old friend, the Pictish beast.

The circle crossed by a line, with two small circles at either side, may be a cauldron, which symbolized rebirth.