Garden of Tian Zi

The Movement dropped me off on the outskirts of Urumqi city, deep in Xinjiang province. They sent me there to get lost in the wilderness of what used to be western China, to stay hidden in one of the few places left on Earth that hadn’t been claimed by the mega corps. It was a dry, windy day, the dust kicking up and the truck’s old diesel engine coughing dirty fumes in my face.

Not much was said. It was just another job. They handed me a bottle of water purification tablets, a thick stack of bills denominated in yuan and a terrarium of frogs.

The frogs were my golden geese, genetically engineered to secrete a protein-antibody mix that was the key ingredient in manufacturing peptide computer processors. My instructions were “take care of the frogs, set up shop, don’t get caught and we’ll be in touch.”

I approached one of the landlords. He was a withered man, browned by the sun and missing a few teeth, probably heir to one of the old tribal leaders. They claimed a lot of the land out here when the People’s Republic of China dissolved.

I told him my name was Tian Zi and I was interested in renting something a little ways out of the city. It was a good way to avoid attention. In the desert, nobody goes sightseeing without a destination in mind.

He took me around and showed me a few options. I told him they all looked like deathtraps. Then he showed me an old Buddhist temple. It was weather-beaten and a lot of the walls had been scoured of their red and gold paint, but it had a stone foundation and stone lasts. I peeled off a few bills, gummed with him for a bit, peeled off a few more and it was mine.

The temple had three rooms, one on each of the east, west, and north sides. On the south side was the gate. It had both doors left, but the hinges would need replacing.

First thing I did to fix up the place was clear the well. It was a narrow one, set in the middle of the courtyard, and ran deep underground. Inside were branches, dirt, some dead animals and discarded beer cans. The cans probably came from some city kids sneaking into the temple for a night of drinking and telling ghost stories.

There was still a rope and bucket intact, so I used them to clean the well out, then shook in about a quarter of the water tablets. A few days and the aquifer would wash it all clean. For everything else, I had to go to town. I tucked the frogs’ terrarium away in the northern room, threw a cloth around the tank walls and headed out.

Now, Urumqi is my kind of city. I’d been through Vienna, Budapest and Cologne lately. I was tired of seeing endless trees and mountains covered in yet more trees. Urumqi had that nakedness to it, bare rock and scrub grasses exposed to the wind. The wind alternated between baking hot and bitter cold, but always had that dry taste of powdered rock and earth salt. The salt made me hungry.

I stepped out onto one of the main streets, a reddish-brown haze of dust in the air and the sun beating down on the back of my neck. Then the beggar swarm found me. Only the old cities ever seem to have them. It takes a while for civilization to rot.

They were the typical bunch, dirt smeared on their faces, loosely sewn clothes and that shuffle walk that says they just never had the self-esteem to learn how to walk upright. I waved them back to get some room, yelling at them in a pidgin of Turkic and Mandarin.

I’m Han Chinese and born in Shanghai, so the Mandarin was no problem. It only took a week of training to get the Urumqi accent down. I even threw on old clothes to help blend in, gray pants that cut off at the ankles, cheap sandals with plastic straps and a white T-shirt. The beggar kids pegged me as a foreigner the minute they saw me.

I didn’t bother with the cover after that. I asked where I could find a good place to eat, and they started pushing and shoving each other, fighting for who got to be my guide. I got tired of waiting and grabbed one by random.

She had those big green eyes that Xinjiang girls are known for, and her black hair was tied up in a braid. It’s a distinct look, the product of thousands of years of Turkish and Mongol nomads mixing with the Chinese traders that did business along the old Silk Road.

I didn’t know what her age was, but she was in that gawky phase of maturity, thin and long-limbed with none of the curves that make a girl worth talking to. Not that I’m sexist. I could care less what someone’s packing between their legs. I just know the difference. Kids are annoying, girls are fun and women are trouble.

She told me her name was Khulan, which I later learned meant “wild horse” in Mongolian. I followed behind her as she trotted along, walking zigzag up and down the street. I was taller than her then, but she ate up distance fast enough to make me stretch to keep pace.

“Where are you taking me, Khulan?”

“Royal Gold Noodle Shop,” she said over her shoulder. Chinese people have a habit of making everything sound like it belongs in the palace at Versailles, and I guess it transferred over to the Uyghurs out west. Usually, the fancier the name was, the crappier the place. But there was a corollary rule to that: the crappier the place, the better the food. Think about it. Who in their right mind would keep paying at a place if it looked terrible and the food sucked?

Royal Gold stayed true to the rules. The walls looked like used toilet paper, and the door was so warped the only way it’d stay shut is if they nailed it closed.

“Nice place,” I said.

“Sure. Money now?” She cupped her hands in front of her, like I was a Merry Buddha and she was offering prayers. I took a bill out of my pocket and held it in front of her.

“Make change for me,” I said.

She gave me a hard look.

“Come on. I’m not paying twenty yuan for a walk.”

“You want to go somewhere else after you eat?” Good. The girl knew how to think.

“Tell you what. You get some stuff for me, meet me back here with it and I’ll give you a hundred yuan.”

She nodded in agreement.

“You got anything I can write on?”

She tore one of the flyers off the restaurant’s wall and handed it to me. I scribbled what I needed on it and handed it back to her. She looked at it for a moment, talking under her breath, counting on her fingers rapidly.

“I can’t buy this much with twenty yuan,” she said. I handed her a hundred yuan note. She winked at me and ran off. I didn’t know if she’d just run off with the money, but I figured what the hell. Make a friend, right?

I stepped into the noodle shop and there was a fat bald chef, sweating all over and pushing noodles around on a flat-top grill. I dropped down onto a stool and asked for a beer, a dark lager that came in a chilled green bottle.

Behind the chef, a long string was nailed to the wall with a dozen or so wooden placards swinging from it. I’m guessing they didn’t have the money to print individual menus. I ordered a bowl of noodle soup with ququ dumplings. It was spicy, filling and cheap, exactly how I like it. I talked some trash with the chef, took note of a few of the faces, stared for awhile at the muted TV in the corner, paid my tab and walked outside.

Khulan was crouched outside the door, smoking a cigarette with a cloth bundle tied over her back. I gave the bundle a shake.

“This mine?”

“Yeah.” She flicked the cigarette on the ground, not bothering to stamp it out.

I put it out for her and then reached for the bag.

“Great. Can I have it?”

“Where’s my hundred yuan?”

“Where’s my change?”

She patted the bundle behind her. “You asked for a lot of stuff and it’s a hot day. I bought a tea.”

I tossed a hundred on the ground in front of her. She unhooked the bundle with one hand and dangled it in front of me. I took it from her and she disappeared almost as fast as I can. Not bad.

The next few weeks were spent setting up. Khulan turned out to be quite an asset, shuttling materials from the city to the temple and taking care of business that would get a foreigner noticed. I took a liking to her. She was smart, fast and didn’t ask dumb questions. I told her she could stay at the temple and she chose to bunk in the western room. I slept in the eastern one.

“What’s with the frogs?”

“Hobby of mine.” I went back to putting screws into the steel frame. I was building a greenhouse for the frogs. They’d start reproducing soon and I needed something bigger than a twenty-gallon terrarium.

“You don’t seem like that type.”

“What type?”

“Dunno. The sit around and look at animals type.”

“Looking at you now, aren’t I?”

She gave a snort and scooted off, hands in her pockets, whistling some old Mongolian tune.

A week later, the greenhouse was done. I dug up most of the stone paving in the northern room, so the enclosure had a nice reddish-brown soil bottom. The walls were made of glass panes in steel frames. I also dug out a very shallow pool. Khulan knew a good potter, so she had him shape and fire a clay frame for the pool. I poured some well water in it and used another water tablet for safe measure.

The frogs the Movement gave me were Chinese gliding tree frogs. They weren’t the swimming type, so a deep pool would drown them. But they needed it for midnight soaks and later on they’d be laying eggs in it.

“You came all the way to Urumqi to grow frogs in a temple? You some kind of exiled monk or something?” Khulan asked.

“Don’t worry about it.”

“What’d you do, Tian Zi? Get a nun pregnant? Kill someone?”

“Both.”

Khulan’s eyes widened at that. “Wow, really? A killer, huh?”

“Cold-blooded.”

“I bet.” She nodded happily. She wasn’t at all bothered, even though I was just saying things to entertain her.

“So, what’s your story?” I asked. “Why the orphan routine?”

I was sitting down with my back to the wall, watching the frogs hop around the dirt and clamber up the glass. She squatted down next to me, inspecting her fingernails before speaking.

“Not a routine.”

“No? What happened? You get dumped off at an orphanage?”

“Got killed in a motorcycle accident.”

“Tough.”

She shrugged. “Sure.”

Something about the way she said that got to me. Maybe it reminded me of my younger sister from back in the day. Maybe I didn’t think it would be a big deal if some orphan girl knew what the Movement was. It’s not like the mega corps didn’t already know about us.

“The Movement’s an organization that helps people.”

“What kind of people?” she asked.

“Underdogs. Small corporations. Brain trusts. Research initiatives.”

“What do you mean?”

“Have you ever been out of Urumqi, Khulan?”

“An old boyfriend took me to ride horses in Karamay once.”

I laughed so hard it hurt my ribs. “What are you doing running off with boyfriends? How old were you?”

“I don’t know. Eleven, twelve.”

“How old are you now?”

“Sixteen. Get on with it.”

I started grinning at her. “Sixteen, huh? I don’t believe it.”

“Get to the point.”

“Well, okay. What’s your citizenship?”

“Don’t have one. Why? What’s yours?”

“Zhao-Xi Combine.”

Her eyebrows rose in surprise. “I’ve seen their stuff. Their cargo planes fly over Urumqi every now and then. You must be rich.”

“I was a board director’s son, but not anymore.”

Khulan whistled in appreciation. “So what happened? Your dad kick you out?”

I shook my head at the memory. “No. I ran away. I wasn’t cut out for it. Too many restrictions, too many expectations and way too much corruption.”

Khulan gave me a blank face.

“It’s all a scam. When the nations broke apart, everything divided along economic lines, right?”

She continued to give me a blank face.

“Have you gone to school?”

She shook her head.

“Okay. Well, think of it this way. You know what a crocodile is?”

She nodded.

“Imagine a crocodile sitting in a lake. It’s just a mean old bastard, swimming around, eating everything it can find, getting bigger and bigger by the year.”

“Sounds good to me.”

“Only if you’re the crocodile. That’s the problem. There can only ever be a few of these monsters. Everything else gets eaten, even other crocodiles. If they’re smaller, they die. We call that a monopoly. The mega corps, the ones sitting on the dense population centers, the ones who hit the ground running with scientific and industrial infrastructure when the national governments started to dissolve, they’re too big. They’re choking off the rest of the world because they keep eating everything and they don’t share.”

Khulan shrugged. “They earned it, right?”

“No. It’s not supposed to be that way. There’s supposed to be regulation. In nature, even the big ones get sick or injured, and then they eventually die. But, in our world, without governments, nobody has the power to stop it. That’s where the Movement comes in. We steal from the big ones and then we sell to the little ones, give them a chance to grow up.”

“Why not just give it to them?”

“Fighting a war with the big dogs doesn’t come cheap. We need the money and the tech.”

She seemed to take that as good enough of an answer. Later on that night, I sat in bed and thought about our conversation. It was the most I’d ever said to her about my real job, and to be honest, it felt good. I was always on one mission or the other; sometimes it was nice to kick back and actually remind myself of what and why I was doing it.

I started harvesting protein a few days later. I used a fine-threaded cloth and strained it through the frog pool to gather the shed skins floating on the surface. It looked primitive, but it worked. The protein from the skins, after some centrifuging, and filtered into an aqueous solution, sold for more than a hundred thousand times their weight in gold. More even.

The solution contained a unique type of protein and monoclonal antibody that was pivotal in the fabrication of peptide computers. The technology was similar to how silicon chips produced binary data, but instead of using logic gates, the processors read the interactions between protein and antibody. That meant instead of only two states of being, it had twenty.

At the time, most of the world was working with a fusion of DNA and silicon. Only a few of the most powerful companies had developed peptide computing. The Movement had gotten wind of it, put together a raid operation, and got what we needed to fabricate our own.

It was the new X-factor. Combined with research software using genetic algorithms to make breakthroughs, companies were getting about ten, fifteen times the amount of research done with the same amount of resources as a company using DNA computing.

I was one of a few dozen production and distribution centers orchestrated by the Movement. We were all single cells, one-man operations that did everything from raw materials to point of sale.

After everything was up and running, I made a call to the number they gave me and an olive-colored jeep rolled around the next day. An agent from the Movement jumped out and we shook hands. He was a skinny guy, short hair, twitchy eyes, and had a real fast walk. But when he talked, he had a voice that made people listen, low and crystal clear.

“Let’s see what you got,” he said.

I showed him inside. I’d made sure to send Khulan to town to buy some stuff, so she wouldn’t complicate things needlessly. “Population should triple within the year.”

He ran his hands along the glass and gave the frame a few stiff pokes. I watched his eyes mostly. They were counting how many frogs.

“You’re going to be able to move a lot. Maybe fifteen grams a month.” I agreed with him. “I’ll set it up then.”

I nodded. “Just send me the contact info ahead of time. I’ll make it happen.”

I reached out to shake his hand when both of us heard the sound of someone breathing. The corners of his eyes tightened, and I finished the handshake, keeping my face expressionless.

He didn’t say anything, but we knew we weren’t alone. The fact I hadn’t reacted meant it was someone I thought was safe. He wasn’t happy about it, but he gave me the benefit of the doubt.

I walked him out the door and he got back in his jeep and took off.

A minute later, Khulan tiptoed in.

I turned to look at her. “I told you to go buy me some papayas.”

“Sorry. I forgot to bring money with me.”

“Don’t give me that shit. When I tell you to go, you go.”

“Whatever.” She rolled her eyes at me. She dodged fast, but I was a lot faster. I kicked her and she went tumbling across the doorway. She scraped her elbows on the stone floor and started coughing violently as she tried to stand up.

I stood looking down at her. “I’m not your buddy.”

She took a moment to recover, sucking air on all fours as she shook her head. “That hurt.”

“It’d hurt a lot more if you got a bullet through the head. He knew you were here. I knew you were here. You’re just lucky I’m an old-timer.”

She gave up trying to stand and sat back on her haunches, holding her sides and wincing. “I don’t even know what you’re talking about.”

“Hope you never do. Now come on. We’ll go into town together.”

She ignored me, sitting on the floor and pouting, while she shuffled her feet to turn her back to me.

“I’ll buy you some red bean cakes.”

She jumped up and followed me out the gate.

To do business, I needed a cover. It wouldn’t make sense if a foreigner showed up in Urumqi and started talking to lots of suits. And I had to create the cover on my own—part of the Movement’s policy. We create our own and we maintain them on our own. If I couldn’t do at least that much, I didn’t belong.

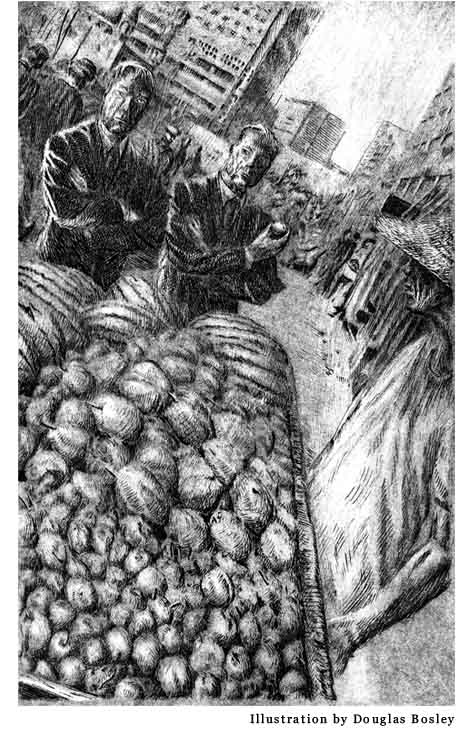

I pretended to be a fruit vendor. For a few months I sold the ordinary stuff, bananas, peaches, papayas, kiwis. Most of the suits came dressed as tourists, pretending to want to eat some honest farmer’s fare on their trip in the vast wilderness of western China. Nobody paid me much attention. I’d mumble stuff under my straw hat, and the suits would pretend to have difficulty understanding.

Khulan put the word out to the other street kids not to mess with me and not to hang around when I was talking to tourists. When the tourists weren’t around, I’d toss them a fruit or two, sometimes a five-yuan note.

After a while, I started selling more exotic fruits. It wasn’t necessary, but I was bored. We tore up a lot of the hard-packed dirt behind the temple and planted a garden. The soil wasn’t too bad to work with, a lot of clay so the acidity was low, but we took care of that with some fertilizers. I had to teach Khulan most everything. She was a city girl and didn’t know much about how to make plants grow. But the garden made her happy, and after awhile, it made me smile too.

I imported a variety of fruits over the Internet, collecting saplings, plant grafts and pouches of seeds from the tiny strip of pavement that was Urumqi’s airport. The first crop we grew were milk oranges imported from Wenzhou.

The fun part of eating a milk orange is the peeling. I remember the first time I handed Khulan one, and she started grinding away at it with a thumb. She didn’t see what the big deal was until she gave it a good tug and a cloud of mist swirled into the air. She gave a short surprised laugh and started peeling more of it, spraying citrus juice everywhere. See, milk oranges are juicier than regular ones, and the juice doesn’t run clear. It’s a cloudy white color, so when you peel it, it starts billowing a sweet-smelling vapor that looks like what comes out of a bucket of dry ice.

After the milk oranges, I started bringing in exotics at a rapid pace. It was almost like a game. I kept trying to think of new ways to entertain Khulan, and I think she was happy to have someone take an interest in her education.

We planted chocolate berries, paw-paws, kiwano melons, lemon meringue fruits, custard apples, eta fruit, almost everything I could get my hands on. We ended up expanding the garden twice, and our hard work caused quite a stir at the marketplace.

At first, I was worried we might draw too much attention, but then I thought maybe it was best to hide out in the open. It’s easier to do business when everyone expects you to talk to lots of people.

It was a peaceful life. I felt a part of myself let go for a while, relax and unwind from the constant tension of moving from one mission to the next. It got to the point that I could swear I was putting down roots.

Meanwhile, Khulan looked healthier and happier than I’d ever imagined. Although, one time, she came home bruised with her clothes torn.

I asked her what happened.

She said, “I fell down.”

“What do you mean ‘fell down’?”

“Sorry. I was clumsy.” She hung her head and a thick silence fell between the two of us.

I let it go and she didn’t say another word. She just went to her room, slammed the door and didn’t come out until dinner time. She had a black eye for three days. I swear I’ve never seen someone look so aggressive while so beat up at the same time.

Later on, I found out the sons of some of the other fruit vendors had tried to beat on her. They called her the fruiter’s whore, and said she was still nothing but a street rat, and that if I ever left, they’d kill her.

They didn’t get away with it. The other street kids had poured into the alley within minutes, and the vendors’ sons were the ones who got mobbed and beaten. Khulan had a roof over her head now, but she would always be one of them. Or at least that’s how the street kids explained it to me. I gave them a couple hundred yuan for their trouble and they were happy.

A week later, I talked to Khulan about teaching her how to fight.

“I know how to fight,” she said. I heard she had managed to kick one of the older boys’ teeth in, but I thought it would make me feel better to see what level she was at.

I put my hands up in a ready position. “Show me.”

She paused for a moment, thinking about it. “I’m not going to fight you.”

“You’ll be all right. Just come at me.”

“Nope.” She shook her head.

I put my hands back down and gave her a look of disappointment. That’s when she tried to kick me in the groin. I blocked it with a knee. She started laughing and ran off.

Later that night, while we were sitting down for dinner, she started asking questions.

“How’d you learn to move so fast?” she asked.

“What do you mean?”

“That time you kicked me. I’ve never seen anyone move that fast.”

There was a voice in the back of my head that said I’d regret telling her about myself, but there was another voice that wanted someone to talk to.

“I’ve been trained by the Movement.”

She popped a grape in her mouth and then a slice of breadfruit. We had so many fruits growing it had given her a decadent palate. One fruit wasn’t enough anymore. She had started inventing cocktails on the fly.

“Training doesn’t make anyone move that fast,” Khulan said.

Usually I never beat around the bush, but I had trouble figuring out how to explain nanomuscles to a street orphan.

“My muscles have been modified. They’re stronger than the normal human.” She frowned, which kind of irritated me. “Okay, imagine my arm is a rope.”

“Okay,” she said, while dangling a cluster of grapes in front of her face.

I held my forearm out to show her. “Now a normal human’s muscles, they’re like a rope made of cotton. But mine . . .” I reached out and flicked one of the grapes, making it explode in a shower of juice. “Mine are like spider silk.”

The demonstration was a little flashy, but it was the best I could come up with. What my muscles actually had were a much denser and efficient layer of artificial myofibrils that attached to my ligaments, tendons and skeletal muscles to enhance their performance. On the surface, I was no bulkier than the average fit male, but beneath the skin, I out-performed even the most gifted natural athletes.

Khulan wasn’t happy with my demonstration. She yelled at me for being a jerk and ran off to find a towel to clean her face. A minute later she was back to asking questions.

“I don’t get it. If you can do that, why are you here in some run-down old place, wearing beat-up clothes and pretending to be some poor fruit grocer?”

I thought about how to explain it to her for a second. Telling her it was my cover was too simplistic and she wasn’t stupid. She was asking something deeper. I told her what one of my mentors had told me.

“The world’s got two types. Predators and prey.”

She nodded. “Rich and poor.”

“Similar, yeah. Well, what do you notice about the two?”

“One eats the other.”

“Right. But other than that?”

“I don’t know.” She thought about it for a second. “One is fat and defenseless and the other one has teeth and claws and stuff?”

“Getting there. Okay, let me give you an example. You have a tiger, right? What’s a tiger?”

“A predator.”

“What’s a rooster?”

“Food.”

“Exactly. Now look at the behaviors of the two. A rooster does what? He gets up in the morning, yells a lot, struts around all day puffing his chest out.”

She bobbed her head like a chicken and started laughing.

“Now a tiger. A tiger doesn’t do any of that. What do tiger stripes do?”

“They make it blend in.”

“With what?”

“With grass.”

“Grass. You see that? A predator tries to look like grass. That’s how you know the difference between the two. A predator always tries to blend in, always tries to stay hidden. A predator doesn’t want to be seen. They can’t eat if people know they’re there. All the prey will run away. But prey? Prey spends all day trying to look like a predator.”

“So that’s why you dress like a farmer.”

I tipped my beer at her before taking a long draw.

Things were going great. The fruit gardens out back were growing nearly out of control, the frogs were bright green, plump and shedding skins every week and Khulan had a way of making me laugh over little things like I hadn’t in a long time. Then the Germans came, two tall men, blond-haired, blue-eyed and clean-shaven with square jaws. They weren’t twins, but they had that factory-made look.

“Kiwi?” I asked.

“Plums,” they both answered.

“I’ve got apples. Do those work?”

“I think we’ll stick with kiwis.”

The code changed every week. It was pretty damn unlikely that some random customer would come by and guess the sequence.

“Here’s the deal. Five grams. More juice than a couple thousand of the best DNA computers could do you.”

“That sounds good,” they both said in flawless English.

“You know the price?”

They tilted their heads at me.

“Every blueprint of H&K’s first-generation products. Prototypes too.”

That started a discussion between them. “That’s a lot to ask,” the one on the right eventually said.

“Standard market price. What you guys got, I can go buy at a trade show. What I got? Only the Movement has.”

“Not true,” said the one on the right. “Zhao-Xi Combine, Yokomitsu Industries, LM-Boer.”

I laughed. “And they’re selling, right?”

The two exchanged looks.

“Didn’t think so.”

“How do we know it’s the real thing?”

I dead-panned. I wasn’t in the mood for bullshit. They both stood there for a few moments, shuffling their loafers.

“Okay, give us some time to think about it. We’ll talk to the board. Get back to you soon.”

I nodded back at them. They took off. An hour or so later, I packed my stall and headed home too. Khulan joined me once I turned down one of the small side roads.

“You’re being followed.”

I had noticed it a while ago, but was waiting two more turns to be sure. “Thanks for the heads-up,” I said.

“What are you going to do about it?”

“Don’t know. You better go though.”

She kept following me silently. We took another turn. They were still there. I counted three in my peripheral vision, but I wasn’t sure how good they were at hiding. Could be a lot more.

“Beat it, Khulan. Get lost.”

“I can get backup.”

“I don’t need backup. I need you to not get hurt.”

She gave me a look. I knew the kind of look, and it was way too messy to deal with right now. “Khulan. Just take off. You stay any longer and they’ll think you’re with me. I can’t watch both our backs at once. I’ll meet you at the house.”

Her eyes were shiny when she looked at me, but she took off and that’s all that mattered.

I took another turn and ditched the fruit cart. I started walking faster. They’d know I was on to them, but that’s what I wanted. If they were thinking now or never, they’d flush into the open. The buildings started flashing by, cloth awnings casting long shadows and old ladies gossiping in crooked chairs. I counted three, four, five. I think there were five after me.

I ducked into a shop, bowed at the owner and pretended to look at some of the pottery he had for sale. Poor guy. I did a fast count to twenty in my head and then stepped to the side of the door. Almost on cue, the door swung open, two large European men stepping inside. I moved behind the first one and rabbit-punched him in the neck. He dropped to the floor, and I kicked him in the temple. He stayed down.

The other one was drawing his pistol, but human reflexes just couldn’t compete with my nano-enhanced ones. I was next to him before he could react, pushing his elbow back down, pointing the gun in toward his chest and pulling the trigger for him three times. I stripped both their guns and waited for the next move.

The shopkeeper was yelling at me to get out, wringing his shirt in his hands and threatening to call the police. I doubted he even had a phone and I doubted even more highly that the local cops would respond.

“Quiet down, unless you want me to shoot you.” I pointed one of the guns at him for emphasis. His mouth widened into an O, and he scooted back behind the store counter. “Stay down, and don’t get up until it’s over.” He lay on the ground as best he could. He had a potbelly though, so he had to curl over on his side.

I looked out of one of the windows to see what they were doing. Nothing was in sight. They were going to try waiting me out, maybe call in more people. I needed to move. “Stay down!” I shouted one more time at the storekeeper. No need to get innocents killed for being stupid. It’d draw attention and I’d probably have to get out of town.

There was an exit out back. One of them would definitely be waiting there. Another would be watching the entrance. That left only the third, the wild card. It was a fifty-fifty chance. Either they thought I’d try to sneak out the back or they’d figure I knew the back exit was cliché and I’d go out the front. The logic went on ad infinitum. I figured what the hell and went out the back.

I heard his breathing before I saw him, but I ducked his first shot and got hit in the leg with his second. It didn’t slow me much. I bowled him over, and I think, more than anything, it was his surprise at my mobility that let it happen. I shoved both guns into his ribs and let it rip. His partner probably figured he was a goner, because the next second I got shot in the back. I felt it pierce clean through me, leaving a decent-sized hole in my side.

I rolled off the dead guy and blind-fired upward. Only a few angles someone can shoot a person from when they’re lying down. I heard a scream and knew I’d guessed right. A woman with an assault rifle crumpled against the opposite building, a bullet hole in her neck pouring blood.

I took off running as fast as I could, trailing blood and hoping the nanomeds in my bloodstream could handle it. A few minutes later, the wounds had scabbed over, but I could tell the damage was very much present underneath.

Khulan was waiting for me when I got back. She helped me into bed, cut up some bandages and gave me a cup of water. I lay down, breathing heavily, hoping whichever mega corp they worked for had dispatched a small team.

The next day, I was walking on crutches. The nanomeds in my body had done a lot of work while I was asleep, but I knew I’d need more for a full recovery.

Nanomeds were a technology in its infancy stage, but the Movement gave field operatives the best they had. They were molecular structures designed to mimic the capabilities of pluripotent stem cells, the only difference being they could transform into specialized cells at a much faster rate. Instead of weeks to become a lung or kidney cell, it took hours.

The nanomeds were specifically tailored to my DNA back at one of the labs, using a skin graft to culture cells, and then reverse engineering them to create stem cells. While actually in my body, they stored themselves in my lymphatic system, taking cues from my body’s immune responses to pinpoint actual locations for repair. The only catch was the nanomeds couldn’t change back once they transformed into a specialized cell.

While I recovered, Khulan helped me around the place, sweeping away leaves, straining the frog pool and taking buckets of water to the garden. I think the sight of me limping around really got to her because next thing I knew she started making it an issue.

“I want to join up.”

“No way.”

“Why not?”

“You’re too young.”

“I can do small stuff. I work for you all the time. Isn’t that like being a part of the team already?”

“You don’t want to be part of this team.”

“Why not? You guys are the good guys.”

“No such thing.”

That managed to piss her off and she stalked out of the room. It took me a few minutes to track her down, but she was just taking care of the daily chores. The frogs needed to eat, and they only ate live food. I had been buying crickets off one of the local farmers, but the large amounts I ordered had him asking questions I didn’t want to answer.

Instead, Khulan had thought of another way to get the frogs food. She sliced up some fruit, left it out in the open and waited for the insects to come. It was the desert. Food was scarce, but insects were everywhere. It’d take a while for them to notice, but once they did, the fruits would get swarmed.

We sat outside, me with my shirt off, sipping hot tea and waiting for the flies to come. Khulan looked at me, making me self-conscious for a second, but I was in shape and she was a kid. We sat this way for about half an hour with her stone-faced, waiting for me to talk while I enjoyed my tea.

“You heal a lot faster than normal,” she said, smoking a cigarette. She told me she’d cut back on it, but I’d catch her lighting one every now and then. I couldn’t stand the stuff myself.

“Perk of the trade.”

“Pretty good perk.”

“Only if you get shot a lot.”

She showed me one of her scarred elbows. “Or get kicked,” she said in an angry tone.

I laughed and put my arm around her shoulder, giving her a hard squeeze.

She snorted and leaned away from me. “So what happens now?”

The question sobered me pretty fast. “I expect we’ll get a visit from the Movement.”

Sure enough, a few hours later, some people from the Movement made contact. I heard the rumble of an old jeep pulling up to the gate, its tires growling over the rough sand. Using automobiles kept us below the radar. Nobody important traveled by road anymore, or at least that’s how the thought went.

I recognized one of the agents that climbed out. His name was Donovan, and he was a big Irish guy. He had a mop of brown hair, an easy smile and broad ham hands. I did a lot of wet work with him down in Panama a couple years back. I hadn’t seen him since, but he was reliable.

The rest of them were new to me, which was standard. An old military maxim is “cut off the head and the rest of the snake will die.” The Movement was more like an earthworm. Cut an earthworm in half and you get two, much better than snakes. So, it was unusual to have more than two or three of us together other than for big operations.

“What’s going on, Donovan?” I shook his hand.

He clapped me on the shoulder with the other hand. “Heard you ran into some trouble.”

“Those H&K people. Can’t work with them no more.”

“Hegel and Kritz? They were bought out last week.”

“I was shot up by people claiming to be from H&K.”

The other agents exchanged glances. Donovan was frowning. “That doesn’t sound good.”

I shook my head. “Nope.” I knew what answer was coming. I felt my guts twist and I looked for a hole in his logic, but there just wasn’t anything to say.

“Pack up time,” he said.

I nodded. It was one of the few times I hated having to agree with common sense. I’d gotten way too attached to the place, to the temple outside Urumqi.

Donovan handed me a syringe of nanomeds. “I’m guessing you’re running low.”

I took it from him and shot it into my left forearm. It would take about an hour or so to kick in, but I was expecting I’d be fighting fit by the next day. “You guys want to take the frogs now?”

“Why not? We got a biokit in the jeep. Shouldn’t be a problem.”

I led them back to the house. Khulan didn’t bother hiding. She watched them with a troubled expression, and her face contorted like she wanted to say something when they started taking the frogs away. I put a finger to my lips and shook my head to let her know now was not the time.

They cleared all the frogs out and cleaned the greenhouse, using chemicals and scanners to make sure no trace of the proteins was left. I gave them the peptide solution I had on hand, about thirty grams, and that was it. I talked to Donovan for a minute before they took off.

“I bet she reminds you of your sister, doesn’t she?”

I wasn’t comfortable talking about my past, but Donovan and I had been through some hairy experiences together in Panama. It makes people close, no matter how you look at it.

“Yeah. She does.”

“Dangerous.”

“I’m a big boy.”

“Take a few days. Say your goodbyes. Then we can ship you out someplace else.”

“Might settle down for a bit.”

Donovan got a look on his face, and I knew that look.

“Don’t even, Donovan. I can still put you on your ass before you even blink.”

He raised his hands in mock surrender. “Hey, I didn’t say anything.”

I couldn’t help laughing. “It’s not like that.”

“Of course not. Never is.” He put an arm around my shoulder and leaned in close. “You know you can leave any time. We’ll set you up somewhere quiet. But I don’t know if we can take the girl.”

“She knows my operation.”

“No big deal. We’re shutting this down anyway. We’ve done our job. Market for peptides is pretty much mainstream by now. We forced their hand. They’ve started selling the manufacturing process. The smaller companies have to pay royalties on it for a while, but they’ll all get the tech within the year.”

“She wants to join.” I could hear the desperation in my voice. I think it surprised me more than it did Donovan.

“We’ll see how it goes. A lot of people owe you favors. May take some time though. It looks real raw trying to bring her in so fast.”

I nodded. There was nothing else to say. We shook hands again, he got in the jeep and they drove off.

Khulan took the news hard. It was painful for both of us, but her reaction made it worse. At first, she begged me to take her along. Then she cried for hours. In the end, she drifted around the temple, ghostlike, smiling to herself sometimes, shoving and kicking at things other times. I tried explaining to her what was going on, but she wasn’t in any mood to listen. I didn’t want to tell her she might be able to join the Movement. She’d just be crushed if it didn’t come through.

She moped around like this for two days straight and I should have been long gone, but it didn’t feel right leaving her like that.

On the third day, I woke early and went to town. I thought it would be a nice gesture, buy some groceries, cook some food, throw Khulan a nice party before I left.

But on the long walk back to the temple, I started to feel a little silly, and a whole lot of helpless. How are steamed carp, fried pork and a tray of sweet egg custards going to make up for the life we’d made together? It felt almost insulting to put a nice face on it, like I was lying to Khulan and disrespecting her intelligence. Maybe I was. But I wasn’t the type who did nothing when he didn’t know the right thing to do.

The first indication I had of something wrong was the distant sound of crackling fire. I gripped my bags and walked faster. Then came the scream, long, loud and anguished. Khulan. I dropped everything and ran.

The temple’s gate had been knocked down, the two columns supporting it, a splintered wreck. There were three guards outside, and I took a shot in the shoulder on the approach. The force of it knocked me back on my heels, but I recovered my balance and leapt as hard as I could into the air, kicking one of them in the chest. I felt more than heard his ribs snap, and I stomped his throat before grabbing his machine gun.

I knew some people from the Movement were in the area because the two other guards got hit by sniper fire and dropped to the floor around the time I kicked the first one. Six of them shimmered into view, their light-refraction suits flickering as they tried to compensate for movement.

“Donovan,” I said.

He saluted me. “Tian Zi.”

“Give me a report.”

“Six hostiles inside, four in the north room, one in both the east and west rooms. Hostage is being held in the north room.”

I felt a lump form in my throat, but I kept it icy.

“What’s her status?”

“We’ve had the temple on sat-surveillance, but we bugged it on that last visit. She should be all right. They haven’t done any major work on her. Don’t think they know who she is, and they might be holding back in case they can use her for leverage.”

“Cake walk,” I said. One of them laughed. I gave him a look and he grew a brain. “Fast and clean. Let’s get it done.”

They scattered. The fight didn’t last long. I made sure to kill the torturer myself, and I used his tools to do it. It was fast, but I got to hear him scream plenty before I was done.

When I came back out of the temple, they had Khulan pumped full of painkillers and were carrying her by stretcher to the jeep. I walked over and took a look for myself. She was in worse condition than Donovan had let on, but I think he did that to spare me the worry. It’s always easier when I see it up close. I can get a grip on it, understand the exact parameters. It’s the imagination that screws with my head.

“You okay, kid?”

Khulan looked up at me, the pain swimming in her eyes. She was unconscious when we rescued her, but she had come around a few minutes after they got her into the stretcher.

“Tian Zi?”

I squeezed her hand, careful not to touch the tips, where the fingernails were splintered. “I’m here.”

“I kept quiet.” She smiled at me, her hair in disarray, but her eyes burning with that wild light she always had.

“I’m proud of you. You did good, Khulan. I couldn’t have asked for better.”

I didn’t know what else to say. It’s not that I wasn’t used to seeing people get hurt out in the field, but I think saying sorry would have pissed her off more than anything.

Her eyes teared up and she rested her head back on the stretcher. The other agents took that as their signal and started walking toward the jeep again. I think everyone was uncomfortable with standing around while I talked to her swinging from a stretcher.

“She’ll be fine, TZ.” Donovan approached and offered me a cigarette.

I waved it away. “Yeah. I know.” I wasn’t in the mood to talk to anyone. It was irrational, but I held it against them that they stood by while Khulan had been tortured.

“Word came in. They’ll let her on the team. We sent a field report on her conduct. She could have talked. She could have said a lot. Even though they already had the intelligence, there’s no way she would have known. She could have talked for an hour, but she didn’t.”

“Thanks, Donovan.” I started walking away before I said something I’d regret. I knew the rules. The Movement only helped their own. Bystanders were off limits. It was hard enough keeping ahead of the mega corps, no need to add to the burden.

He grabbed me by the bicep. “Hear me out, man. You want to hear this.”

“I want to go see if my garden’s all right.”

“Get it together, TZ. It’s gone. First thing they did was run through it and try to see if anything was there.”

I felt a hot surge rush through my body. I wanted to go back inside and stab the torturer a few more times. “Fine. Finish what you have to say.”

“She did a good job. You taught her well. When they were cutting her up, she screamed and cried, and carried on. I swear, even we thought for a second she didn’t know anything. She’s a natural. We could have gone in earlier, but we knew you wanted her on the team. We gave her a chance to prove herself, and she did.”

It was a bittersweet feeling. At least she had taken my words to heart: be a tiger, act like grass.

“She’ll get fixed up and then go in for training. I don’t know when you guys will see each other again, but it’ll happen.”

“I’ll count on it,” I said.

Donovan left me alone so I could see what my garden had become. Everything was a mess. Trees cut down, roots torn up, fruit smashed to pulp and flowers shredded all over the dirt. I sat down in the middle of it all and I cried like I hadn’t since I was a boy. They gave me space. We shared the same struggle. They knew how lonely it could get.

I cried until my eyes flowed like rain. But there was a delicious aroma floating up around me. All that smashed fruit, the insects buzzing around, the smell of tree sap and crushed flowers in the air. I felt like I was sitting in the placenta of Creation, and I drew strength from it. This was what we were fighting for. This was the Movement.

We had grown a garden here, and now it was gone, but watching all those insects come crawling out to feed and looking at those seeds dot the soil, I knew I could leave, and my garden would still be here. It wouldn’t look as pretty, and soon enough those plants would start fighting amongst themselves for who would have the run of the place, but life would go on. The struggle would continue.