The Dizzy Bridge

Come see the birdsong!” Lin’s tiny frame burst through the swinging back door of Brindisi’s studio.

“Lin, I’m working. Working, remember? I can hear the bird some other time.” Brindisi’s words were stern, but he couldn’t keep a smile off his face. All morning he’d been chiseling a smoke stone, but the work was going poorly and Lin’s arrival more than welcome.

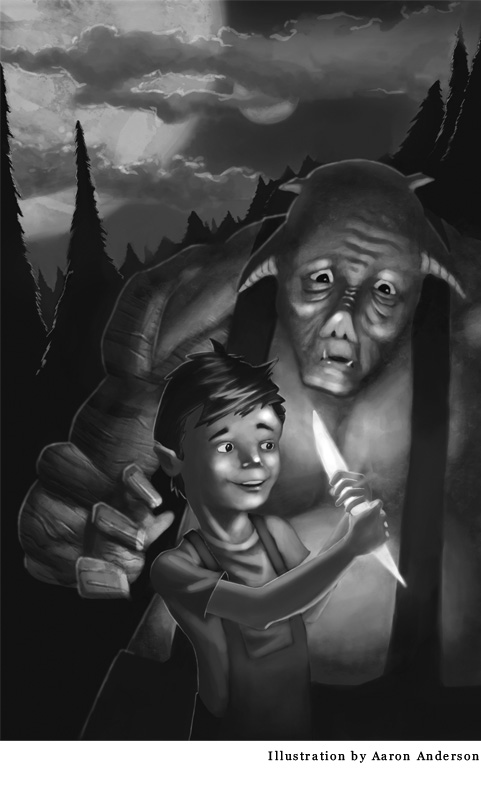

Lin scampered past the chunks of stone and clay, wood and metal littering the studio. Brindisi bent down and Lin came charging up, vaulting himself onto Brindisi’s wooden arm. Brindisi enclosed him in a careful hug—the boy was smaller than some of the stones he crushed between his prosthetics.

Most people were scared of his mismatched arms, but not his little neighbor. Lin had clambered right up on him the first day they’d met, as if Brindisi were his own personal playground. He didn’t allow Lin to sit on his metal arm, for fear of the heavier chisels, polishers, hammers and clamps hurting the child. But his wooden arm, with its gentler “fingers,” could pose no threat to Lin’s safety. The day Lin Cala named Brindisi’s wooden arm “my swing” was the first day Brindisi had chuckled since arriving in Frotola.

“What are you making, Dizzy? Something for the bridge?”

“Use your eyes. What do you see?”

“Stone. Mud. Muddy stone. Come on, come see the birdsong!” He tugged at Brindisi.

“Come see the bird.”

“Comeseethebird. But she’s kind of a song too. You have to see her!” He brushed his curly hair out of his eyes and squinted slightly, as he did when he was concentrating. “I think . . . I really think she’s beauty, Dizzy.”

“She looks beautiful.” Brindisi smiled at the child’s enthusiasm. Yesterday’s lesson must have caught the boy’s attention.

“Shelooksbeautiful. Come see her!”

“What about our work, my apprentice? What stone am I using?” Brindisi had given Lin a wooden box full of sample stones to study.

Lin sighed, squinted at the stone in front of him. He leaned back, his bare heels kicking into Brindisi’s belly with soft little thuds. The fresh nuttiness of Lin’s sweat reminded Brindisi of a healthy soil stone.

“The stone’s weird. Like moving clouds or something, but dark. It’s not like my rainstone, exactly, but maybe a thundercloud stone?”

“Very close. A smoke stone, to preserve heat, but also to ward against fire. What do you see carved in the stone itself?”

Thud, thud, thud went Lin’s little feet.

“Ears. A big big eye. Too many legs. A wing. Some kind of animal?”

“What kind?”

“Many kinds.” Lin stuck out his lower lip as he peered at the smoke stone. “I don’t think Mamma would like it.”

“Indeed, I doubt she would. For your mother and for your village, this would be a demon, Lin. A creature not of one kind.”

“Like you?”

“Yes, like me.”

To make a bridge anyone could cross, yet no one could harm—the kind of bridge Brindisi had been sent here to make—required many components both opposing and complementary, many components “not of one kind,” for by its very nature a bridge connects that which otherwise cannot be connected. Only after he’d been forced to fashion new arms for himself—after he himself became “not of one kind”—had Brindisi truly understood this about bridge-making.

“But are you a demon, Dizzy? Like Mamma says?”

Brindisi’s answer caught in his throat. How to tell the truth to the boy? “Your mother believes me to be a demon. And in her own way, she is right. But I would disagree.”

“Me too, Dizzy! I disagree too! Let’s go see the birdsong—the bird, before Mamma gets home.”

Brindisi hesitated. The stone was calling.

“Come on! She’s like you, Dizzy!”

“I thought you said she was beautiful.”

“She is. But she’s got wrong parts too.”

Brindisi chuckled, grateful for this little brute of a boy who’d wiggled so deeply into his heart that Brindisi could hear the words but not feel the sting.

“Well, run and dampen some cloth in the stream—we must keep the clay fresh and the stone cool. Then we’ll go see this bird of yours.”

Lin hopped off his arm, grabbed a cloth from the nearby mosaic countertop and started out the back door.

“And use your eyes, Lin, remember you never know when we—”

“—might find a new stone!”

To Brindisi’s surprise, Lin led him toward the center of town, past the circle of tall cypress trees, down into the grassy amphitheater. Not quite a year in Frotola and most of the villagers still stared when Brindisi walked by, shifting to make a careful moat of space around them: a few crossed themselves; one heavy-set man cursed; Maria, the baker, smiled at Lin but avoided eye contact with Brindisi.

In the center of the grassy stage stood a large pink-veined birdbath, its sides curving upwards, seamlessly blending into what looked like a giant egg, flecked with silver and blue. Not only the birdbath pedestal, but also the egg itself, had the look of faux marble. Was that what Lin had meant by wrong parts?

“Look, look, she’s hatching!” said Lin.

The egg rocked in its birdbath. Wind chimes tickled the air. Once, twice, three times laughed the wind chimes as the egg rocked, louder each time. Brindisi’s breath caught. Out of the egg emerged a giant peacock, richly plumed in lime green wings, dusky wine breast feathers, and cradled by contour feathers of cerulean blue.

“See?” said Lin. “Beautiful! I told you.”

“We’ll see. Why did you say she has wrong parts?” On the bird herself, Brindisi looked for metal or wood, earth or stone, but saw only feathers covering one long uninterrupted silhouette.

“Just wait!” Lin hopped up and down in excitement.

A murmur rose from the crowd; toddlers were hoisted onto shoulders; older children and adults pressed forward. From north, south, east and west, four seemingly ordinary peacocks flew. The just-birthed giant peacock rose vertically into the air, like a bejeweled dagger. Not a giant peacock, Brindisi realized, but a woman illusionist.

A crown of golden feathers trembled atop a face of brilliant unquilled blue. The sky-colored skin continued past her throat, dipping dramatically between her wine breast feathers to her navel. Her naked legs were barely discernible against the sky, and disappeared completely as her four peacocks converged and unfurled their tails, haloing her in an iridescent display.

Whatever the woman had done to so deeply drench herself in the illusion of being a bird disturbed Brindisi. He shivered, in spite of the noon sun. How could the villagers consider his own created arms more sacrilegious than the spectacle before them? Yet instead of cursing and signs of the cross, the bird-woman was met with applause and cries of awe.

At first the dance was simple—swoops, swirls, a few pirouettes. Then her peacocks circled faster as she flew in elaborate spirals and figure-eights. The wind chimes grew louder, falling into the cadence of her beating wings, the crowd clapping along with the dance. At the peak of applause, the illusionist flew straight up into the air, flying far above her peacocks—a feathered jewel of caught sunlight. The crowd hushed.

In the silence, one chime rang, like sung laughter, then feathers exploded in a kaleidoscope of fireworks. Sparkling feathers showered down, the peacocks themselves disappearing within the torrent, the feathers vanishing as they touched ground.

“A miracle,” said one villager.

“An angel!” cried the heavy-set man.

“A demon,” said Brindisi, under his breath, “and, perhaps, a witch.”

The bird illusionist hovered high above the town square until the entire crowd had taken up shouting. Little Lin’s voice was one of the loudest. Then, with tremendous elegance, she plummeted down, entering her birdbath with an enormous splash, sending a blue and silver umbrella of water across the crowd, filling the amphitheater with the smell of sweet figs and pure salts. The villagers gasped as the water fell, then erupted in cheers, whistles, laughter, and a ringing chorus of bravas.

Brindisi licked the metal cylinder of his forearm, tasting the wetness, before quickly spitting it out. The undertones of magnesium, saltpeter and ether confirmed his suspicions that she’d trained at the School. He’d once analyzed the illusionists’ distinctive brine for its preservative qualities, but otherwise, he’d avoided their laughing company.

The thunderous applause lasted long after she climbed out of the birdbath. She managed only a few bows before the children mobbed her, begging for feathers.

“See, Dizzy, she’s beauty, right?”

“Well, she looks beautiful, yes.” Such shows of extravagance without substance had driven him from the School, and away from sculpture, even before he’d lost his arms. He’d never developed an appreciation of beauty for show, not for use.

“Can we go talk to her? I could bring a feather back for Mamma. Then she wouldn’t be mad even if she finds out I was with you.”

He should take Lin home, the sooner the better. Return him to his mother, not let him be further drawn into the empty spectacle of the illusionist’s art.

“Please?” asked Lin.

Most of the children already clutched colorful feathers in their hands, but one or two insistent parents shooed their children away empty-handed, fleeing before his and Lin’s approach.

“And who might you be, little one?” asked the illusionist.

Lin’s face flushed under her gaze. “I’m Lin! You were beauty! This is my friend Dizzy! He says you look beautiful!” The boy had a firmer grasp on the various incarnations of the word “beauty” than Brindisi had realized.

“Ah.” She turned to Brindisi, revealing eyes the same dusky wine color as her breast feathers.

“A beautiful performance, madam.” He gave a slight bow of his head. The illusionist bowed her head in kind.

“May I please have two feathers?” asked Lin. “One for me and one for my mother?”

“Of course, little one. For you, a flying feather. Throw it in the air, it will fly all on its own.” She handed him a wingfeather—the edges such a light green they disappeared into a halo in the sunlight.

Lin took it solemnly in his small hands. “Thank you, my most beauty.”

Before Brindisi could correct him, the illusionist laughed. Her laugh was almost too loud to be polite, with a catch in the center, as if she were laughing around a pebble caught in her throat.

“And for your mother, something pretty and carefree.” She plucked one of her golden crown feathers and tucked it behind Lin’s ear.

“Thank you, thank you, my most beauty!”

“Don’t say that, Lin.” Brindisi’s tone was sharper than he’d intended. “That’s not correct. You may say thank you, beautiful one. Or thank you, my beauty.”

“Thankyoubeautiful—”

“Or, you may say ‘Thank you, my most best beauty,’ and my heart will be yours to keep, little one.”

Lin peeked up at Brindisi to see if his tutor had something else to say. Brindisi avoided the look. He regretted correcting Lin publicly. They could discuss this back at his studio, while working with clay, wood, stone—solid objects which were what they seemed. He would introduce Lin to the concepts of flattery and treachery.

“Thankyou”—Lin gulped—“mymostbestbeauty,” one hand on each of his new feathers.

“For that, my treasure, I will give you my heart.” And she tugged deep within her breast feathers. She tugged twice, and then, wincing, finally produced a deeply silver, nearly blue stone—as if someone had taken a perfectly symmetrical feather and spun it like a top.

“Keep it someplace safe, little Lin, for anyone who carries my heartfeather will always feel loved.”

Lin nodded so hard Brindisi was afraid the child might fall over. The child put his flying feather and his mother’s gift into his pocket in order to hold the heartfeather with both hands.

“And you . . . Dizzy? We are long gone and far distant from the School, but there can only be one man who has tree and earth for one arm, stone and metal for another. Are you not the famous sculptor?”

“Fame is an illusion more suited to your art than to mine. And I am no longer a sculptor. I make bridges.”

“Please. I did not mean to give offense. I would be honored to offer you a feather.”

“Such fragility would not fare well in my fingers.” He held up a hammer of granite and a chisel of serrated steel.

“A feather to remember fragility then.” Without breaking his gaze, she plucked a feather from her lip and let it drop.

Brindisi’s eyebrows furrowed; what trick was this? A feather from skin? Which was true, the feather or the skin? And why would this illusionist want to play such a game with him?

“Catch it, Dizzy!” said Lin.

Brindisi reached out, pinching the tiny blue feather in his gentlest clamp of moss. He could dispose of it later, when Lin wasn’t around. Or save it for a lecture on deception. That is, if it didn’t vanish by this time tomorrow. The illusory art was not known for its longevity.

“Thank you . . .” He didn’t know how to finish the sentence.

“Beauty, Dizzy! Say my most best beauty!”

The illusionist laughed again, the pebble still there, making her sound as if only part of her laughed. Something of the pebble lodged in Brindisi’s throat, but still he could not say something so inappropriate, even to please his Lin.

“Thank you, little one, but you have your eyes and your Dizzy has his. I will be your most best beauty. That is more than enough for me. You, sculptor—”

Brindisi winced.

“—or bridgemaker, if you prefer, you may call me Avila.”

Brindisi bowed deeply. Lin copied him, his head brushing the tips of the grass. By the time they’d finished their bows, the only sign of Avila was the giant birdbath cradling her silver and blue egg, whole and uncracked.

“Lin Cala!” a too familiar voice cried from the circle of cypress trees. “Lin Cala, get over here right now!”

Brindisi feared the golden feather Lin was hastily pulling out of his pocket would not be enough to placate Mamma Cala’s fears and fury.

A week later, Brindisi was chiseling skyseed when Lin came running in through the swinging back door.

“Dizzy! Maria fell asleep again while she was watching me, so I ran out of the house to come help you!” Lin hurdled himself onto Brindisi’s wooden arm, hugged him fiercely.

Brindisi cradled him against his chest, stroking Lin’s hair with his softest polisher of thistledown. “My apprentice, your mother doesn’t want you to be here.”

“But I missed you, Dizzy. I’m bored all the time now. Maria never teaches me anything.”

“Nonetheless, you should hurry home before she wakes up. We must win your mother’s trust again.”

“Don’t worry. When Maria falls asleep, she sleeps for a long, long time. Look! I brought my new feather to show you.” Lin threw a silver and indigo-tipped feather up into the air of Brindisi’s studio. The feather descended in spirals until it touched the ground, and then started circling back up again.

“I must admit, she is quite a witch.”

“Dizzy, don’t say that. That’s a bad word.”

“I’m sorry, my apprentice. Most consider it a compliment.”

“Don’t call her a compliment! It isn’t nice!”

“No, no, Lin.” Brindisi chuckled. “Compliments are nice, good things. At least the true kind. A false compliment is flattery, which is not such a bad word, but means a bad thing.”

“What kind of bad thing?”

“A way of trying to get what you want by lying to people.”

“Oh.”

“But a true compliment, where you really believe something good about a person and then you tell that person, is as precious and valuable as . . . as . . .” He tried to think of something that Lin would understand. Why a true compliment was sweeter than roasted figs, and how a compliment given without any selfish desire was its own vein of river-clay. “As important as the heartfeather that Avila gave you.”

“Oh!” Lin’s eyes grew round as two owl’s eggs.

“‘Oh’ is right.”

“I asked my most best beauty if she could teach me to grow feathers and fly like her. She laughed, but said she had to fly away soon, and looked sad. Dizzy, why would she be sad?”

Brindisi looked out his back window, past the blocks of marble, into the dark green life of the forest. He could almost hear the stream, if he concentrated. Ever since he’d seen the illusionist’s flight, the stream shivered its own cascade of wind chimes. How to explain to Lin what cost the School demanded, when he was not even sure himself what cost the illusionist had paid? “Perhaps she is homesick.”

“Homesick is to be sick of home?” Lin asked.

“No, sick from missing your home, my apprentice.”

“How could I ever be homesick? My home is right here!”

Brindisi laughed. “Indeed, my apprentice, but if you learned to fly, perhaps you would fly away from here and then you would discover what it is to be homesick.”

“But couldn’t I always fly home, Dizzy?”

“Perhaps, perhaps not.”

“Maybe that’s why my most best beauty looked so sad! She’s forgotten how to fly home! Maybe you should send her home, Dizzy.” Lin sat sidesaddle now, and leaned his body into Brindisi’s chest. His dark curly hair came just to Brindisi’s chin. “I don’t want her to be sick.”

“Nor do I.” He didn’t want Lin to get hurt—not through Avila, and not through him. If this witch was necessary for Lin’s happiness, he would see what he could do. He quickly kissed Lin’s head. So quickly he hoped the boy didn’t even feel it. “Don’t ask her again to teach you until I talk to her, okay?”

“Okay. Dizzy, is that a white smoke stone?” Lin brushed his hair back, squinted.

“No, this is skyseed. Very rare. A smooth stone will ensure a clear sky, pulling any wisp of cloud into itself—very useful for a lookout or sightseeing bridge. A jagged stone will create clouds and fog, keep a bridge concealed. Now hurry home, before Maria misses you. I have work to do.”

“Boring, sleepy old Maria.” Lin hopped off his swing, headed toward the back door.

“Don’t—”

Brindisi intended to warn Lin to be careful, that a glimpse of knowledge without enough context, like too much skyseed in a narrow bridge, could let you see things too far off, too distant to safely reach. How one moment of dizziness could cause you to lose your step, fall.

“—don’t forget to look for new stones! I know! You too, Dizzy!”

And Lin was gone.

The night was moonless, but the stars were bright, and the road beneath Brindisi’s feet well-worn. Only the baker’s lamps burned as Brindisi walked quietly to the amphitheater. No wonder Maria was always falling asleep.

Just inside the cypress trees, he stopped to listen, but heard only wind, no chimes. As he approached the giant birdbath, his breath caught—a ring of water glistened in the starlight. A leak. He didn’t know much about the illusionist’s art, but he knew that without her bath of brine Avila wouldn’t be able to keep flying her dance.

Each step made a small puddle in the grass. A significant leak. What would Lin’s birdsong do? He tapped lightly on the marble with a silver tuning mallet, heard the answering cry of the crack, out-of-tune and loud enough he worried anew.

“It’s too late, sculptor,” called Avila’s voice from inside her egg.

“Bridgemaker,” muttered Brindisi, under his breath. More loudly, he said, “Avila, I can fix this.”

“Why?” she asked, only the tips of her crown feathers peeking out of the top of the eggshell. “Why would you fix something that only looks beautiful?”

“I fix far uglier things all the time.”

The former pebble in her laugh had grown to the size of a rock, and what should have been a laugh came out only as a wheeze. “What a great comfort.”

Brindisi swallowed. “What I mean is that I will do my best to not mar what beauty is already here.”

His offer was met with silence. The cool of the brine seeped into the seams of his boots.

“Avila, Lin told me you looked sad. For his sake, I came to see if I could help you. I thought you might be homesick, which I was not certain how to mend. But a crack, a crack I can mend.”

“Not all cracks can be mended.”

“Perhaps. But every crack that can be understood can be bridged. At least temporarily.”

“Spoken like a bridgemaker, but where is the sculptor?”

Brindisi cleared his throat, but held his tongue. Typical of an illusionist’s question—presumptuous in its intimacy, deceptive in its innocence, willfully ignoring the truth of what she already knew. He would not match Avila’s rudeness with his own. “Avila, Lin is worried about you.”

“I had not meant to let the little one see my sadness. How is he?”

This question he could answer. “He is well. Full of mischief and delight, sneaking out on his mother, always learning. For his sake, allow me to fix your birdbath.”

“I have already told him I must fly away soon.”

“But he wants to learn to fly like you. What you called your heartfeather is his greatest treasure.”

“You do not call it my heartfeather?”

Brindisi shifted his weight in the soggy grass. Another question. He hated talking to illusionists. Always it was this way—they asked questions they shouldn’t ask, and if he told them the truth, they’d get hurt. Sweat began to gather along the parallel scars where his arms attached to his back.

“Please, allow me—”

“—you do not call it my heartfeather?”

“I would call it a beautiful illusion, from a gifted illusionist.” It was the best he could do.

“I see. What of the feather I gave you?”

“I . . . it would be an honor, if you would allow me to fix your birdbath, Avila.”

“Where is the feather I gave you?”

Sweat dampened Brindisi’s armpits. “I no longer have it.”

“Where is it?”

“I buried it in the ground.” More brine trickled into the gap between the uppers and the soles of his boots, more sweat gathered under his arms, ran down his back. “I was curious to see how it would react. If your illusion would . . .”

“Would what?”

“Hold up to earth. Withstand dirt and water. Regular dirt, regular water.”

Chimes of glass clinked loudly, and Avila’s eyes appeared above the edge of the marble shell. Her crown feathers drooped. “And what have you found out?”

Brindisi’s feet were now quite wet, bathed by the leaky birdbath. Under Avila’s gaze, sweat and oil ran down his torso, including an unpleasant dripping sensation along the parallel scars of his back. In spite of his body’s best efforts to cool him down, his heat rose as his patience ebbed.

“It disappeared. It did not last.”

“Yes. Did you find out anything else?”

“After it disappeared, there was nothing else to find out.”

“You are wrong, sculptor. That is precisely when there is everything to find out.”

“Then, illusionist, I assure you, I found everything out.” He should have known better than to try to talk truthfully to her, even for Lin’s sake.

Avila pressed herself up onto the edge of her shell, revealing her face for the first time that night. Feathers fell from her crown, echoed by a smaller fall of flakes from her chapped lips. It was difficult to be certain in the starlight, but it looked as if she were not losing feathers, but rather shedding skin.

“Thank you, bridgemaker, for your visit. Thank you for your honesty. Tell Lin . . . tell Lin to take care of my heartfeather.”

Sweat ran down his legs, dripping into his boots, and as he looked at her pale, patchy face, he finally felt the night’s chill. “Avila? Do you want me to fix your birdbath? Or send a message to the School? I fear . . . I fear you are gravely ill.”

He thought she might be trying to laugh, but this time not even a wheeze was possible, just a jagged scrape against gravel.

“What I want is for you to leave.”

A voice from the bakery halted his run. “Bridgemaker! What’s your hurry?”

“Maria! Good evening.” Brindisi bowed formally, aware that with his sopping boots and sweated-through shirt, the bow would have to do what his clothing and middle-of-the-night appearance could not. Never before had Maria actually spoken to him. “I must fetch something from my workshop, to mend Avila’s birdbath.”

“Oh. Well, okay then.”

Brindisi bowed again, started running.

“Bridgemaker, do you want a hot berry scone?”

A second time he halted. “Thank you, but no, I must hurry.”

“Good luck.”

He ran, his heart beating louder as he wondered at Maria’s offer. He must thank Lin. Or, perhaps, Avila. He ran faster.

Brindisi knelt beneath the olive trees behind his studio, painstakingly re-sifting through the soil where he’d last seen Avila’s lip feather. He’d crushed marble and smokestone to make a warming, healing marble paste, but had hoped to find some trace of Avila’s lip feather before he returned. Despite what she’d implied in their conversation, he couldn’t find anything. If he didn’t understand her, how would he be able to mend her birdbath?

“Dizzy.”

Brindisi jumped at the whisper.

“Lin! Why aren’t you in bed?”

“Maria came to my window, told me you were going to help fix my most best beauty’s birdbath. I want to help.”

“Maria should have kept her mind on her scones, and you, my apprentice, should be asleep. Quickly now, off to bed.”

“But I want to help.”

“You can help most by going home and going back to sleep.”

Lin’s face stretched tight in the starlight, a rapid blinking the only sign of his fight against tears. “But I am your apprentice, and my most best beauty needs our help. And I brought her heartfeather. See?”

Lin held out the wooden box Brindisi had made for him. The sight of the box, and the knowledge of its contents, caused Brindisi’s eyes to blur with unexpected tears. Perhaps Lin understood enough for both of them.

“Come, my apprentice, we must hurry.”

Lin quickly climbed onto his swing. Brindisi ran.

The birdbath was cracked wide open, the last of the bathwater running onto the grassy stage. Curled in the center lay Avila, nearly featherless. Her skin was a washed-out gray, but for here and there a faded patch of sky blue.

“My most best beauty!” cried Lin, leaping off Brindisi. “I’ve brought you back your heartfeather!” Brindisi limped after him, his ankles complaining of the night’s run in his soaked boots.

Avila lifted her head, her bare skull small and fragile in its nakedness.

“See, see,” said Lin, his little fingers deftly unlocking the box. He lifted out the solid heartfeather, as deeply silver and blue as the day she’d given it to him. “I brought it back for you!”

“It is yours, little one, yours to keep.” No wind or chimes in her voice anymore, only gravel and stone. “My work here is done and now I must fly away. Keep my heartfeather as my blessing. Remember then, you will always feel loved.”

“No, no, no, I want you to have it!” said Lin. His hands were shaking as he tried to push the heartfeather into her breast. “Dizzy, Dizzy, come help!”

Brindisi knelt beside the prone Avila, brushing his polisher of feathers around Lin’s hands. Gently applying pressure, not knowing how to help, or what to do. His plan had been a good one: mend her birdbath with the prepared paste; trust Lin’s understanding to provide the keystone; send for a healer from the School. He’d not realized how far advanced her illness was.

“Avila,” he said, “what can I do?”

The illusionist’s face was white and colorless as the starlight. “You should not have come back. Certainly not with—”

“He is my apprentice and he wanted to help you.” The words sounded too formal. He lowered his voice. “I didn’t realize.”

“My most best beauty! Please, please, don’t die!”

Brindisi flinched. He should have known better than to let Lin come.

Lin’s little hands fluttered, trying to brush Avila’s heartfeather back into her chest. “Please don’t die, my most best beauty! Dizzy, help!”

He would not let this happen. He quickly gathered the two largest shards of her birdbath, bridged them together with the marble paste.

“What is all this talk about dying? Sculptor, put those silly stones down and come help me up.” Avila struggled to lift herself onto her bony forearm.

Brindisi knelt by her side, supported her with his wooden arm, but held tight to the mended marble with his metal one.

“Come now, little one, listen to me, I want you to hold my heartfeather and sing me your favorite song, very loudly. For I must leave now, that much is true; my birdsong here is done, and I need a new song to fly me to my next nest.”

“But I’m not a very good singer,” said Lin.

“It doesn’t matter. Just sing with all your heart. I want my next birdsong to have an even bigger, prettier heartfeather than the one I gave to you. Will you do that for me?”

“Can Dizzy sing too?”

“I don’t know; can you sing, sculptor?”

Brindisi didn’t know what to say.

“No matter. You sing, Lin; it will be enough. Your big friend will carry me to the trees, so I have a high place from which to start my flight. You can do that much, can’t you, sculptor? Carry me to the trees?”

“Of course.” Brindisi hesitated, the mended stone was set, it would hold water now. He offered it to Avila. “Avila, I have bridged the first cracked stone, see, it’s not too late, it’s—”

“Sculptor, to carry me you will need both hands.”

The helplessness of hot tears threatened. “But—”

“But there isn’t much time for me to fly to my next nest.” She coughed. “Now, please.”

Brindisi released his hold on the mended stone, picked her up. She was heavier than he’d expected, like an uncarved slab of marble, and cool to the touch. Her head rested on his wooden arm, as if it were a pillow. His metal arm cradled the back of her knees.

“Little Lin, please sing.”

“Maybe you’ll think it’s a silly song,” said Lin. “Mamma used to sing it to me, a long time ago.”

“I know it will be beautiful, little one,” said Avila.

Brindisi and Lin started walking toward the cypress trees.

“Sing, Lin. Please sing,” she whispered. “Sing into my new heartfeather.”

Lin took a big breath, and sang.

Ring out the day, my darling

Ring in the night, my sweet

Avila felt lighter in his arms. Brindisi didn’t know if that was an illusion too. He looked down. She was completely featherless now, with no patches of sky blue left, just gray, cold skin that looked as if it were being drained even of the gray.

In the starlight, tears shone on Lin’s cheeks, but his voice was clear and open. Brindisi wondered at the boy’s strength.

Ring me dreams to call the dawn

Ring me unwept dreams to keep

They were almost at the cypress trees when Brindisi heard a soft sigh of chimes, a feathered exhale disappearing into the night. Between his arms he felt the absence of weight. The boy still sang.

Ring in tomorrow, my darling

Ring me dreams to help me . . .

Lin’s voice trailed off. They’d reached the cypress.

“She’s gone, isn’t she?” he said, staring straight ahead.

Brindisi looked down, seeing the grass between his boots and the empty space between his arms. “Yes, Lin.”

“Was it too late for her heartfeather?”

“No, Lin, it was . . . just in time.” Brindisi groped for the words, like modeling in river-clay, but with his mouth. “For she needed you to hold the heartfeather while you sang your song.”

“Do you believe that?” asked Lin.

Brindisi was silent.

“Dizzy?”

He had nothing to offer but the truth. “No, Lin. I don’t.”

“I didn’t think so.” Lin wouldn’t look at him.

“But that’s what Avila would have said. And she’s not here anymore, so I wanted to try to answer you the way she would have.”

“I think you’re right. You did a good job pretending to be her, Dizzy.”

Brindisi couldn’t bear to hear the measured tones of Lin’s voice. “Your song, Lin, I think she liked your song.”

“Yes,” said Lin, “I bet she would have called it beauty.”

Brindisi turned and knelt. Eyes downcast, Lin still clutched Avila’s heartfeather. Although Brindisi wanted to physically lift Lin’s chin and pick him up with his swing of an arm, Brindisi knew he had to bridge this moment some other way.

“Lin. She would have called your song beauty.”

“But you wouldn’t call it beauty, right?”

“Right, Lin.” Brindisi spoke slowly, carefully, as if he were carving the keystone of a bridge. “I would call it . . . I would call it . . . mymostbestbeauty.”

Lin looked up at Brindisi with wide eyes—eyes so wide that Brindisi could see his own face reflected back. Brindisi was afraid to smile. He wanted his apprentice to know he meant what he said, a true compliment.

“Promisemymostbestbeauty?”

Brindisi thought of Avila and her wind chimes: the delight of her peacock dance; the generosity of her feathers; the pebble she’d tried to hide in her laugh; and of the heartfeather she gave Lin and what she’d said it promised. Sometimes extravagance makes its own substance.

Brindisi took a big breath and told the truth. “Promisemymostbestbeautypromise.”

Lin gasped. Reflected in the watery pools of the boy’s eyes, a flash of colorful feathers. Brindisi didn’t turn; he knew there would be nothing to see. Instead, he inhaled, savoring Avila’s last illusion, discovering what there was to find out. He smelled figs and earth, brine and clear water, cypress and marble, feathers and wind.

They avoided the village on the way home. Lin didn’t want to be carried, so it took a long time, but Brindisi didn’t think either of them knew what to say to Maria quite yet.

“Dizzy. My most best beauty’s heartfeather . . .” Lin choked a little on fresh tears, and stopped walking. Gently cupped in his hands, the blue and silver glittered in the starlight.

“Yes, Lin?”

“It’s—it’s kind of like a stone, isn’t it? Could it be a new kind of stone?”

“My apprentice.” Brindisi didn’t know if he was responding to the longing in Lin’s eyes, or if he actually heard the distant cry of chimes. “Indeed it could be.”

“Do you think we—can we use it for the bridge?”

Now more than ever he wanted to make sure he only spoke the truth to Lin. “I don’t know, Lin. I don’t know. But I promise you, we will try.”

Lin threw himself onto his swing, squeezing Brindisi more tightly than ever before.

Brindisi, gently, squeezed back.

As he carried Lin home, Brindisi imagined how he and Lin could sculpt a peacock into the town’s bridge. A peacock carved out of enough smooth skyseed that the sky would always be clear. How they could sculpt it such that on moonless nights the tail would fan outwards, lift completely free of the stone, and reveal a blue and silver egg. An egg carved of heartfeathers, smelling of sweet figs and pure salts, and sounding of wind chimes.

Perhaps that might conjure this night, might honor Avila, might show how beauty can teach us our own fragility—perhaps that, at least, might be true enough to last.