Gone Black

1.

Hargas Base had been Code Black—total security lockdown—for a full two weeks before Staff Sergeant Manny “Outhouse” Gutierres saw the thing he shouldn’t have seen, asked the question he shouldn’t have asked.

He entered the secured area of the base’s sewage treatment plant a little earlier than usual that evening. He was running ahead of schedule—a great rarity—and wanted to finish with the prisoner and get back to his quarters, perhaps get a decent night’s sleep for once. Two armed guards, posted at the opening in the hastily erected partition wall that marked the boundary of the secured area, let him through without a word; they knew him by then. One of them, a muscular man with a long scar running down the left side of his face, nodded at Manny as he passed.

The partitions cordoned off a large section of the sewage treatment plant’s main floor, isolating one of the four sedimentation tanks. Manny and his team at the plant—whom he lovingly called Maggots—had been tabbed to modify the tank, converting it to a watery cage for the prisoner. The specs had been given to them by the Intel agent in charge of the prisoner—a civilian by the name of Donald Gilmore.

Manny stepped carefully over power cables strewn across the treatment plant floor. Gilmore, busy with his instruments, remained unaware of Manny’s presence. Manny hung back for a few moments to watch the man work.

An impressive array of hardware surrounded the modified tank, including a battery of cameras—some perched on the maintenance deck, some clamped to the rim of the tank, and of course one at the observation window. These fed into a bank of monitors perched atop folding tables. A waterproof transceiver—suspended by wire from the filtration grate that had been welded over the tank to prevent the prisoner from escaping—hung in the water to record every utterance the Walphin made, and to talk back to it, once communication had been established. A set of speakers on a small table of their own broadcast Walphin vocalizations—seemingly random clicks and chirps—while a separate computer logged and collated the noises. The monitor pulsed in an ever-changing prismatic display.

Gilmore, sitting with his back to Manny, tapped some keys, and the speakers emitted a burst of rapid clicks. He glanced toward the monitor displaying the video from the observation window camera. The Walphin, just visible on the far side of the tank, simply floated near the surface. Smooth gray skin, wide head with blunt snout, long sleek body. A quadruped on land, but with webbed digits and powerfully muscled limbs adapted for water. Manny had never in his life seen anything so hideous.

That Walphins were also murderous bastards probably didn’t help his perspective.

Gilmore tapped another key, and the burst repeated in a higher register. He again looked toward the observation window monitor. The Walphin jerked and dove for the bottom of the tank. Even the way it moved, with such sinuous, alien grace, repulsed Manny.

Gilmore was scribbling a note in a binder open on his lap. Manny opened his mouth to say something, but movement on the monitor stopped him. The Walphin pushed off the bottom of the tank with its tail and shot toward the surface, heading straight for the hanging transceiver. The alien caught it in its jaws and twisted. The wire suspending the transceiver snapped easily. The Walphin spat it out, then turned and sped back to the far side of the tank. The transceiver sank; Manny watched its progress on the monitors.

Gilmore swore and banged a hand on the table in front of him.

“You’re talking to it?” Manny said.

Gilmore started and spun, his face a mask of frustration. A thin man in a pale green civilian suit, he had curly dark hair, narrow features and a weak chin. “What are you doing here?”

“I came to check the latrine unit.”

Gilmore shut the binder on his lap and set it aside. “Manny, you really need to let me know when you’re coming. I wasn’t expecting you for another half-hour.”

Manny held up a hand, annoyed. “Hey, fine. Whatever you say.”

“Thank you.” Gilmore rubbed his forehead.

“I thought you couldn’t communicate with it yet. I thought that’s what this was all about—learning its language.”

Gilmore sighed. “I can’t communicate with it. I’m just trying to establish a baseline.”

“Didn’t look like that to me. Looked like you were having a conversation . . . and it didn’t like what you had to say.”

Gilmore straightened, stood. “I’m sorry for snapping at you like that, Manny. You just surprised me, that’s all. Go ahead and take care of the latrine, since you’re here.”

Manny took a deep breath, swallowed his irritation. Gilmore was his ticket out of here, if his promises could be believed. Best not to dwell on certain details, then. Best to let it go, if he could. “Fine.”

He went to take care of business. This detail grew more troublesome daily.

Of course, Gilmore couldn’t be bothered to handle the latrine, and neither could his guards. He also wanted access to the Walphin limited to the barest minimum, meaning Manny—who had been detailed to Gilmore for the duration of the man’s stay, however long that might be—couldn’t even delegate the job to one of his Maggots. So it appeared that his greatest contribution to the war effort to date would be emptying alien shit. Join the army; live the adventure.

In addition to the tank, Manny and his Maggots had also built the latrine unit from Gilmore’s specs. It consisted of a length of half-meter pipe with a plate of stainless steel welded over one end, and a self-sealing rubber flap that gave inward fitted over the other. The pipe rested horizontally on a set of braces, so that the Walphin could swim to it, push its back end in through the rubber, excrete, then withdraw, leaving behind its alien waste. Vents, cut along the length of the pipe and covered with ultrafine filter material, minimized backflow. Chains would raise and lower the unit for easy removal and emptying, via a makeshift trapdoor that had been sliced with cutting torches into the grate over the tank.

One of Gilmore’s guards—usually the one with the scar—would accompany Manny on the maintenance deck, accessible by ladder, that hugged the rim of the tank along its far side. The guard’s job was to keep a weapon trained on the trapdoor while it was open. Manny hauled the latrine from the bottom of the tank himself, using a hoist attached to chains wrapped around either end of the pipe. The relatively weak gravity of 47 Ursae Majoris D made this a merely difficult task, rather than an impossible one. Usually, the Walphin sulked at the other end, seeming to watch him, studying Manny with those black, lifeless eyes, perhaps pondering how he would taste.

This time, apparently still riled by the incident with the transceiver, the alien swam in deliberate, continuous circles near the center of the tank. Scarface stood tense beside Manny, assault rifle at the ready.

For his part, Manny had a hard time concentrating on the job, keeping one eye on the prisoner at all times. If the thing made a move for the trapdoor, he resolved, he would let the latrine drop and get out of Scarface’s line of fire.

This was the closest he’d been to it since Gilmore had first brought it in. It seemed to have lost some of its bulk, and the uniform gray of its skin had become a bit blotchy.

Manny finally got the unit up. As it hung before him, dripping water, he removed the rubber seal and emptied the contents into a waste bin. The effluent was dark and oily, with a bitter stench that gagged him. Years of working with sewer gases had afforded Manny a tolerance for unpleasant smells, but this was like nothing in his experience. Scarface wrinkled his nose, too.

Emptying the unit took longer than usual. The alien shit seemed more viscous than it had been, soupy.

Manny replaced the seal, lowered the latrine to the bottom of the tank, closed and chained the trapdoor, all without incident. Scarface visibly relaxed. He exchanged glances with Manny, said, “That damned thing will never know how close I came just now to blowing it away.”

“Your boss wouldn’t like that very much.”

Scarface flapped a hand as if swatting at a bothersome insect. He slung his rifle and made his way down the ladder.

Manny used a loading platform to lower the waste bin to the floor. From there, he would wheel it to Cold Storage, where it would be hauled to the airless surface of 47UMaD. It would freeze instantly, neutralizing any germs the Walphin might be carrying. The Cold Storage personnel would deposit the frozen waste in a trough on the west side of the base, as far from the greenhouse domes as possible.

As he wheeled the bin past Gilmore, who was once more intent on his instruments, Manny paused. He wanted nothing more than to finish the job and get back to his quarters, but something stuck in his mind. That was when he made his second mistake.

“Uh . . . does it look OK to you?”

Gilmore looked up. “What do you mean?”

“The Walphin. Do you think it’s OK? It’s not . . . well, sick or anything, is it?”

“I’m sure it doesn’t like its circumstances. Other than that, it’s fine.”

Manny supposed Gilmore would know. He took care of feeding the alien, from a freezer unit he had requisitioned, in which he kept a supply of meat and fish from the base stores. In addition, Gilmore maintained a small, heated tank that resembled an aquarium and held what looked like nothing more than milky water. “Special additives,” Gilmore had said. “For the prisoner. We’ve had some highly trained experts working on them, based on everything we know of Walphin anatomy and biology. They require a very delicate balance.” Periodically, he introduced the additives into the larger tank. Both the freezer unit and the additives tank stood against the partition wall.

Gilmore produced one of his let’s-be-friends smiles—a toothy grin, goofy in its way. “The prisoner isn’t sick, Manny. Thanks. And again, I’m sorry for snapping.”

“No problem.” Manny glanced over his shoulder at the big tank, stealing one last, lingering glance at the alien before he left.

2.

Throughout the next day and the day following, the incident with the transceiver lingered in Manny’s memory. Gilmore’s obvious lie rankled, pushing even the essential weirdness of the Walphin itself to the back of his mind.

It had been captured at Alpha Mensae A. A UIS Heavy Armor assault force had taken on two Walphin battle groups there in a major engagement. UIS casualties had been high, eventually forcing a retreat, but not before the assault force had annihilated the infrastructure the Walphins had erected there. No attacks would be forthcoming from Alpha Mensae A anytime soon.

According to Gilmore, UIS troops had managed to board one of the Walphin orbiting command platforms, where they’d found the prisoner. It was the highest-ranking enemy ever taken, he’d told Manny. Walphins fought to the death, and the few that had been captured alive tended to die quickly.

And no one knew how to talk to them.

For security purposes, Gilmore had chosen to operate in a remote, classified location—hence Hargas Base, a forward supply depot. And he had another reason for choosing Hargas Base—the ice mines.

The ice beneath the surface of 47UMaD was the reason Hargas Base had been built. The water irrigated the hydroponic farms that provided food for the front-line UIS forces. Now that ice served another purpose: Gilmore needed a lot of fresh water for the prisoner.

Everyone stationed at Hargas Base, Manny included, had unwittingly become stars in a major operation critical to the war effort—not that anyone off 47UMaD could know about it, with the base gone black.

Gilmore replaced the damaged transceiver with a new one, encased in a small wire cage the Walphin couldn’t get its jaws around. Manny tried to forget about what had happened, but it nagged at him. He had a hard time concentrating on his daily work, unable to stop thinking about the Walphin, the way it had acted, the way it looked. He was spending too much time in his head; he needed some perspective.

He needed to talk to Resa Quinn. She was probably his best friend on base, but they’d hardly spoken since Gilmore’s jump transport had dropped into orbit around 47UMaD—just too busy, he supposed. Or it might have been something else.

He visited her quarters on the evening of the sixteenth day since Gilmore’s JT had arrived, since the base had gone black. He dropped by unannounced, unsure if she would respond had he called first.

She answered her door dressed in a robe, her cropped hair spiky and damp, a towel draped around her neck. She stood a full head shorter than him, slight of build but wiry—the result of daily tae kwon do practice—with angular features and a fair complexion. She regarded him blandly, neither moving aside to let him enter nor slamming the door in his face. “Hi, Manny.”

“Is this a bad time?”

“For what?”

“Never mind. I’ll come back.”

“You’re here now. What do you want?”

Manny looked up and down the corridor, mercifully empty for the moment. “Can I come in for a second?”

The faintest of creases crossed her brow, but she let him in.

Manny had known Sergeant Resa Quinn ever since she’d arrived, nearly two years ago. She worked in Irrigation, allocating water from the ice mines to the rest of Hargas Base. She and Manny worked together often, and had even become off-duty friends in the process. Irrigation was not her life goal, Manny knew. She was studying to be a medic.

Her quarters were neater than his. A basket of folded laundry sat on the small couch; the steel sink in the tiny kitchenette was empty of dishes. On one wall were stills of a handsome man with the same angular face as Quinn’s, and three smiling children—her brother and his kids, killed in the merciless—and infamous—Walphin bombing of Newhome.

Quinn shut the door and turned to him, one hand on a hip. “What’s on your mind, Manny?”

He sat on her couch, rubbed his face with his hands, stretching the skin. A day’s growth of beard rasped. “I had to talk to somebody.”

She leaned against the wall, arms crossed, waiting.

He wasn’t sure where to start. “I wouldn’t ask if I didn’t think it was important.”

“Other than to come in, you haven’t asked anything yet.”

“I was wondering—” He cleared his throat. “Wondering if you have a few minutes to come to the treatment plant with me.”

“Gosh, thanks. I can’t think of any place I’d rather visit on base. Breaks my heart to turn you down, but I have to work in the morning and—”

“I want you to see the prisoner.”

Her sarcasm evaporated. She looked away. Very quietly, she said, “Why?”

“I need your opinion.”

“On what?”

“I need to know if I’m making too much out of something.”

“Such as?”

“I don’t want to tell you before you get there. I want you to see the prisoner first.”

“Isn’t that a restricted area now?”

“I can get you in. If you’re quiet.”

She glanced at Manny, then at the stills on the wall behind him. “I don’t know if I can do that.”

“Just for a few minutes.”

She pushed herself away from the wall, presented her back to him. “It doesn’t matter if it’s a few minutes or a few hours, Manny. I don’t think I can do it.”

He saw the tension in the set of her shoulders and held his tongue.

She stood silently for long moments. The airy whisper of the ventilation system was the only sound. Finally, she spoke, without turning around: “I’ve been avoiding you since that thing got here.”

In a neutral voice, Manny said, “I noticed.”

“You know why?”

“Bad memories, I figured.”

She shook her head. “No. I mean, yeah, that’s part of it, I guess.” She looked over her shoulder at him. “But the truth of it is, the thought of having that damned alien here scares the hell out of me.”

“Hey, my Maggots built that cage. It can’t hurt you.”

“You sure about that?” She faced him, arms still crossed. “You’ve heard what everyone’s saying, haven’t you? The word is that the fish is carrying some kind of implanted bomb, that it’s just waiting for a chance to escape, get to the greenhouse domes, and blow itself up. Cripple the base.”

Manny had heard no such thing. “That’s crazy.”

She went on as if she hadn’t heard him. “And suppose it can’t escape? Suppose it decides to just detonate itself right there in the treatment plant, taking as many humans with it as possible?”

Manny stood. “Resa, I’m telling you, that’s nuts. That Intel guy, Gilmore, has checked that alien six ways from Sunday. It doesn’t—”

“Come off it, Manny. You know how it is. Nobody here is a fan of Intel Branch. Those jackasses haven’t produced any useful intelligence since the war started.” In a lower voice, she said, “Maybe if they had, a lot of innocent people would still be alive.”

Manny had no answer to that. He hung his head. “Resa, I wouldn’t ask if it weren’t important.”

She was silent in reply.

“Never mind,” Manny said. “Sorry I bothered you.” He headed for the door.

As he passed her, she said, “Wait.”

He stopped, looked up.

She pulled the towel from around her neck. “Give me a minute. I need to change.” She crossed the living room and turned down the short hallway leading to her bedroom/bathroom.

Manny waited by the door. Quinn emerged a few minutes later, dressed in a plain white overshirt and wrinkled pants. “Let’s go.” She caught the quizzical frown on his face and sighed. “Yeah, it scares me. But I’d be lying if I said I didn’t want to see this thing. Maybe I need to look it in the eye.”

“Fair enough,” Manny said. They went out.

They passed near the gym and through the rec hall—both mostly empty at this hour—before boarding an elevator to take them down to the treatment plant.

“You mean you really haven’t heard those rumors, Manny?”

He shook his head. Most of the conversations he’d had since the Walphin had arrived had been strictly business. He’d been too distracted to notice. It was passing strange.

The elevator reached the maintenance sublevel. A sign pointed the way to the treatment plant. They headed in that direction. The corridors down here—warm, stuffy, sporadically lit—were deserted at this hour.

Manny said, “People are cutting me out of the loop? Why?”

She shrugged. “Maybe they don’t like you being so cozy with that Intel man.”

He banged a wall. “I was ordered to do that! Christ!”

“People are funny.”

“People are idiots.”

There was a T-junction ten meters ahead. The treatment plant entrance was around the corner to the right. Instead, Manny veered off course, leading Quinn down a flight of steps to the left.

“We going to the mines?” she said.

“We’ll cut across on this level, and come up on the other side. There’s a fire exit toward the rear.” His ID badge was coded with clearance to deactivate the treatment plant’s fire system—mandatory for the sergeant on duty, in case of false alarms. Gilmore had asked for the badge when he’d first arrived, but Manny had balked. “You can have the backup, but I need this one,” he had told him. “I can’t get into the personnel files for my staff without it. Or my own quarters.”

Gilmore had considered. “Keep it for now, until we can get you a different ID—one that doesn’t allow you to shut off the fire alarm. Nothing personal, Manny. ID badges can get lost—or worse, stolen.”

Manny hadn’t gotten around to ordering the replacement from Security yet.

The sublevel below Maintenance housed the mining facilities. Manny and Quinn passed several freight elevators that led deep into 47UMaD. Drills and other rock-chewing implements filled equipment racks. Motorized carts, used for hauling gravel, stood silent in their stalls. The entire floor stank of old grease.

“I’ll tell you something else, too,” Quinn said. “Word is the Walphins have gone quiet since Alpha Mensae A.”

Manny was incredulous. “And how would anyone here know that? The base has gone black. We haven’t had any outside communication for two weeks.”

“I read it in the last newsdisks we got just before the lockdown. I can show you the articles, if you don’t believe me.”

“Maybe they’re licking their wounds.”

“Or maybe they’re doing something else.”

Such as preparing for a major attack. Both Peleus and Newhome had been preceded by a notable lack of Walphin activity on any known systems. And then the bombings had come, both of them complete surprises, striking where the fish had never struck before.

“Wonder what human settlement they’ve found this time,” she said. “Maybe this one, eh? At least it’s a military target.”

“We’re highly classified. You know that. Those JT pilots make three or four extra jumps when they come or leave here, just to throw any possible chasers off the trail. The colonies were easier for the fish to find.” This last slipped out before he had a chance to censor himself. He winced and glanced at her for a reaction.

She proceeded as if she hadn’t heard it: “None of those extra jumps will mean shit if the fish have figured out a way to track jump transports.”

“And how would they do that?”

“By sneaking some kind of beacon on board one of them.”

Manny halted again, put a hand out to stop her. “Are people saying that, too?”

“No.” Quinn looked away. “Not yet, anyway.”

“So that’s just your theory? That the Walphin allowed itself to be captured so that it could lead its buddies to a military installation?”

“Why not? You know how important Hargas Base is to the war effort, Manny. It’s bad enough that we’re not able to make any new shipments while we’re Code Black. But if we were shut down permanently—”

“Don’t you think someone would notice if the fish were broadcasting some kind of signal? And just how long would it take for that signal to reach Walphin space? A few decades, maybe.”

“There’s a lot about them we don’t know. And that includes their technology.” She resumed walking.

He quick-timed it to catch up with her, again stopped her with a hand on her arm. “Hey. Seriously. Don’t go spreading that rumor. People would freak out.”

She looked at his hand, then at him. He withdrew it.

“What’s this Intel man promising you, Manny? Is he gonna straighten out that mess with General Levine?”

“Oh, hell.” He started walking again, more quickly than before.

She matched his pace. “I’m right, aren’t I?”

“I never should have told you about that.”

“Levine was a jackass. You did the right thing, Manny.”

“He still is a jackass. And a powerful one, at that.”

General Levine, commander of Third Army, a decorated thirty-year veteran, family man, and all-around swell guy, had long been rumored to dally with underlings. Manny had learned the truth of those rumors when Levine took up with a friend of his, back when he’d been stationed at Third Army Command, on Mars. Tearful and guilt-ridden, she had confessed the details of the affair to Manny. She’d tried to end it, but Levine had threatened to have her dishonorably discharged if she dared.

Manny, infuriated, had reported Levine to CID.

And someone there had leaked it to the media.

Manny never found out who it was. It certainly hadn’t been him. Not that it mattered.

Levine was powerful enough to squash any serious internal investigation. But the media proved more difficult to handle. With the story public, he could not retaliate against a whistleblower—not openly, anyway.

So the underling accepted an honorable discharge in exchange for her silence. Manny couldn’t blame her for taking the deal. As far as he was concerned, she’d earned it. The investigation ended, the media lost interest and Levine’s official record remained untarnished.

But his wife divorced him six months later.

In short order, Manny was transferred from Third Army Command HQ to Hargas Base. He’d been there ever since, long enough to earn the nickname Outhouse.

He’d long since given up applying for transfers. His applications were all rejected. His position at the treatment plant had somehow been designated a critical billet. Hargas Base would be his home until the day he left the army. And with a war on, that day wasn’t coming anytime soon.

The girl he’d been dating prior to the transfer had stopped responding to his commdisks years ago. His parents still wrote him regularly, but his father’s health was failing. Surgeries and cancer treatments had left him weakened. His mother’s letters were always upbeat, focused on the positive—a little too positive, Manny thought. Every week, he expected to get the news that his father was gone.

Gilmore claimed he had connections. If this operation goes well, I’ll be grateful, he had told Manny. And so will the people who sent me.

“You did the right thing,” Quinn said again.

“Yeah, fat lot of good it did me.”

They reached the stairwell on the opposite side of the sublevel. It led to a little-used back corridor, and the treatment plant fire door.

A sign hung on the door, red letters on a bright yellow background: Fire Exit—Alarm WILL SOUND.

Manny produced his badge. “Just a few minutes. Keep it quiet.”

She took a deep breath, nodded.

He waved the badge in front of the scanner. A metallic click sounded, and the indicator light flashed green.

Manny pulled open the door. It creaked, but the alarm remained silent.

They stepped inside, approaching the Walphin tank from behind. Manny nervously eyed the cameras mounted in various positions, but as he’d hoped, none of them appeared to be recording. Gilmore had a limited supply of memory and recharging the batteries was time-consuming. He recorded only when he was in the area.

Manny led her around the tank to the observation window. He glanced toward the entryway in the partitions; Gilmore’s guards, stationed on the other side, would need only peek inside to see the two of them in here. But their attention would be focused on anyone approaching from the main entrance or the dock doors. So long as Manny and Quinn were quiet, the guards would never know they were here.

Quinn glanced around, taking in Gilmore’s workspace—the monitors, audio equipment, the special additives tank. Only then did she look in the window.

The Walphin was on the opposite side, next to the latrine unit, essentially an oddly-shaped shadow at this distance. It was preternaturally still.

Caught it in the middle of taking a shit, Manny thought. How perfect.

Quinn stood as if made of stone. Color slowly drained from her face, making her appear drawn, withered, aged beyond her years. Her lips moved silently. One hand went again to a pants pocket, pulled out a miniature stills frame. Manny recognized it even from a distance—the one containing the pictures of her brother’s family.

He stood to one side, his gaze alternating from Quinn to the prisoner. Neither one moved. For long moments, he forgot about everything else—Gilmore, the guards, what would happen if they were caught. All that existed was the tank, the Walphin, and the two of them.

He leaned in, whispered, “Are you all right?” The steady rumble of the ventilation system, louder on this level, covered his voice.

She blinked rapidly, as if coming out of a daze, then turned to him. Matching his whisper, she said, “It . . . yeah. Yeah, I’m OK. It’s not so bad.” She looked through the observation window again. “Not so bad at all, are you? Not anymore.”

“I was wondering—” He suddenly felt stupid, but he forced himself to finish. “Wondering if it looked like it might be sick to you.”

“Sick? Since when did I become an expert on Walphin biology?”

“I thought with those medical classes you were taking . . .” He stopped, hearing how ridiculous he sounded. “Oh, hell. I haven’t been thinking too clearly lately. I thought it looked like it might be sick, and Gilmore doesn’t think so, and he’s—”

He became too conscious of his surroundings, at how precarious their situation was. He glanced over his shoulder at the opening in the partition wall, saw only the backs of the guards posted there. And the prisoner remained utterly motionless on the other side of the tank. Manny had never seen it remain so still for so long—as if it knew who was watching it.

He dismissed the thought, with an effort. “Look, just tell me I’m out of my mind, and we can get out of here.”

“Manny, why is this bothering you so much?”

And he didn’t know how to answer that, how to tell her that he suspected there was much more to this situation than Gilmore was telling him. He couldn’t tell her why he felt that way; even he didn’t know, not yet.

“This was a really bad idea,” he said. “I’m sorry. We should go.”

She looked again through the observation window, peering. “Well, even if I could tell a sick Walphin on sight, I’d probably need a closer look than this. Doesn’t it ever move?”

The Walphin had been immobile since they’d come in. It hadn’t even surfaced for air. And Manny realized it couldn’t be using the latrine, as he had first supposed. The angle was all wrong. The prisoner was perpendicular to the pipe.

Something was very, very wrong.

Manny bolted for the maintenance deck, leaving Quinn where she stood. “Wha—?” she said.

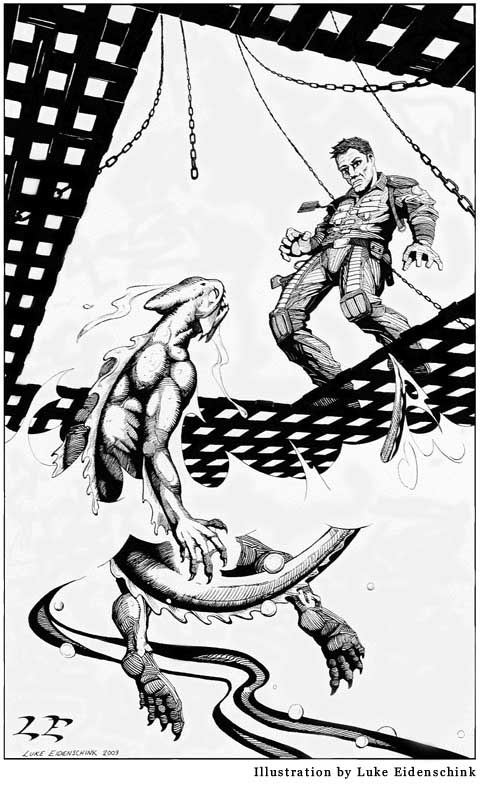

He climbed the ladder and mounted the deck. At the tank’s edge, he knelt and peered into the water. From this vantage point, he could see more clearly: the Walphin had somehow gotten its tail wedged under the pipe, between the braces that kept the unit from rolling. It couldn’t get to the surface to breathe.

“Christ.” Manny unlocked and opened the trapdoor, grabbed the hoist, and began frantically hauling up the latrine. As he did so, the Walphin came free and floated slowly to the surface. Manny got the unit out of the water and maneuvered it to the maintenance deck. He let it drop with a bang that reverberated throughout the plant. He went to the trapdoor and knelt again, the grate biting his knees. The Walphin was directly below him, floating at the surface, an arm’s length away. Its appendages and tail appeared ragged, hanging limply.

“Oh, God. Oh, God. Shit!” Not knowing what else to do, Manny reached for the prisoner, thinking he could perhaps nudge it.

The Walphin spewed water from its blowhole, momentarily blinding him. Manny recoiled just as the thing lunged. It came out of the water and snapped at the air just inches from his nose. Then it fell back, twisted and dove, dousing him with a flick of its tail.

Manny fell backward, or tried to. The toe of one shoe got caught in the grate. His momentum twisted the ankle. Pain flared. Manny cried out.

He groped frantically for the trapdoor while working to free his trapped shoe. In his mind, he saw horrific images of the Walphin escaping from the tank, overpowering the guards, and heading straight for the greenhouse domes. He jerked his toe free and got hold of the trapdoor. It slammed to with a clang.

Gasping and wincing, he pulled himself back to the maintenance deck. Only once he got there did he permit himself to look into the tank.

The Walphin was still inside, thank God. It swam the perimeter with astonishing speed, thrusting with its powerful tail. Every few seconds, it rammed the wall with muted thuds that Manny could feel.

“Manny? Manny!” Quinn was calling from the base of the ladder.

Sopping wet, he dragged himself to the edge of the deck and looked down. Quinn stood below him, eyes wide. “Did it—”

Some of the water dripping from him must have hit her. She stepped back with a cry, her face twisted with disgust, as if it had been vomit instead of water. “Jesus, did it attack you, Manny? Did it bite you?” She brushed at her arms and clothing.

Teeth gritted against the pain, Manny said, “No, I don’t—”

Shouts came from the other direction. Manny looked up. Gilmore’s guards had heard the ruckus and were running toward the tank, rifles raised. Quinn was blocked from their sight—for the moment.

Manny turned back to her. “Go. Now.” But of course she couldn’t leave through the fire exit without setting off the alarm, and he had no time to throw her his badge. “Hide. They only saw me. Hide and wait for them to clear out.”

She bolted before he’d finished speaking. He didn’t see where she went. By that time, the guards had arrived at the tank. Scarface shouted up to Manny: “What the hell are you doing here?”

Slowly, painfully, he got to his feet, hands raised, wobbling as he struggled to maintain his balance. “I think,” he said, breathing hard, “that I should go to the infirmary.”

3.

His ankle was sprained. The medic on duty wrapped it tightly and advised him to keep ice on it as much as possible. Ice came at a premium on Hargas Base; he would have to make it from his personal water rations. The medic gave him some pain patches and released him.

Lieutenant Morrison, his immediate superior, confined him to quarters, pending an investigation.

Manny kept his story simple, sticking as close to the truth as possible: he had sneaked into the restricted area on his own, to get a better look at the Walphin than he could with Gilmore hanging around. He told all the rest exactly as it had happened.

He said it first to the MPs. Then to Lt. Morrison. Then, finally, to Lieutenant Colonel Ezrin, the base XO, who came to his quarters to personally question him.

Neither the MPs nor Morrison asked about Quinn. Manny deduced that she had gotten out of there unnoticed.

His lieutenant had yelled and harangued until he was red in the face. Manny expected to be busted a stripe or two, but Morrison assured him that a court martial, a dishonorable discharge and jail time were more likely.

Manny, still buzzing from the pain meds, accepted the news with bland detachment. General Levine would have his ultimate revenge, after all. But at least Manny would finally get off Hargas Base. He wondered if they would let him see his father before hauling him to the brig.

Colonel Ezrin had a different reaction.

His brow protruded from his bald pate like a ridge of stone, but his voice was calm, controlled. His lined features remained impassive. He carefully considered every answer. By that time, Manny’s ankle was beginning to throb again, but he held off taking more meds; no point in fuzzing his senses with the XO in his quarters.

Ezrin sat across from him at his tiny kitchenette table. The colonel steepled his hands in front of him. He had known Manny since Manny’s arrival at Hargas Base. Ezrin had been the one who’d detailed him to Gilmore in the first place.

After a long silence, the colonel said, “This isn’t like you, Gutierres.”

“This . . . it’s an unusual situation, sir.”

“Maybe so, but that doesn’t change the fact that you’re lying to me.”

“Sir, I—”

“You’re transparent as domeglass, Gutierres. You’d make a lousy card player.”

Manny, who did occasionally play poker—though he hadn’t been invited to a game since the Walphin had arrived—already knew the truth of this.

Ezrin sat back and let his hands rest on the table. “In fact, that’s the real reason you’re stationed here, isn’t it? Your honesty?”

Manny recognized the rhetorical question for what it was and held his tongue.

“You’re protecting someone, Gutierres. Who? Not Gilmore, surely. Not one of your own people, either; they’ve all seen the prisoner firsthand.” The Maggots had been present when the Walphin had been loaded into the tank—a one-time deal Manny had arranged with Gilmore, to forestall future curiosity. And it had worked, so far.

Ezrin went on: “Your friend over in Irrigation, then? She’s lost some family to the Walphins, I believe.”

Manny ducked his gaze, knowing it gave him away, but unable to stop himself.

Ezrin stood. “All right. That at least makes more sense.”

Manny started to rise, too, but Ezrin waved him back into his chair. “As you were, Gutierres. Rest that ankle.” The colonel pulled his cap from a pocket and fitted it over his bald scalp. “I believe it’s unlikely you’ll ever try something so stupid again, so I won’t bother warning you about that. Think you can still empty that latrine unit, in your present condition?”

Manny took several moments to process what he heard. “Beg your pardon, sir?”

“You’re still detailed to Gilmore. I personally can’t think of any worse punishment than having to empty alien shit, can you?”

“Uh . . . no, sir. But—”

“Yes?”

“I don’t think Gilmore will like that very much, sir.”

“Gilmore should be thanking you. You very likely saved the prisoner’s life.”

The thought had occurred to Manny, but he had been keeping it to himself. None of his interrogators had appeared receptive to such an observation.

Ezrin said, “Anyway, I don’t give a shit what Gilmore thinks. I didn’t invite him here. He’s as much to blame for what happened as you are.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’ll explain the situation to him, and to Lieutenant Morrison.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“When you’re not on duty, you’re confined to quarters until further notice. Understood?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Idleness and isolation—bad for morale. Discipline on this base has been shot to hell since that damned thing arrived. I aim to restore it.”

“Yes, s—”

But Ezrin was already headed for the door. Manny almost let him go, but found he had to say something else.

“Colonel?”

Ezrin paused at the door, looking back.

“Sir, the prisoner . . .” Manny paused, taking time to frame the words. “I don’t understand how it got caught under the latrine. I . . . don’t think it was an accident.”

Ezrin’s stare bored into him.

“And there’s more,” Manny said. “I think Gilmore’s been communicating with the Walphin. I mean really communicating. He knows how to talk to it, better than he’s letting on.” He expected Ezrin to override him at that point, but the colonel only stood, waiting. “That latrine unit, for example. How did the prisoner know how to use it? We know they’ve caught other Walphins. Maybe Intel has already figured out their language.”

Ezrin nodded slowly. “And what do you suppose he’s saying to it?”

“I don’t know, sir. He—” Manny shook his head. “None of this makes any sense. I still don’t understand why he brought the prisoner here in the first place.”

“He told you his reasons, didn’t he?”

“Yes, sir. Secrecy, and the ice mines. But that’s crap. Secret as this base may be, Intel HQ’s got to be more secure. And he wouldn’t have to scrounge for water there, either. Unless—” He stopped. He didn’t like the picture he was getting.

“Unless what, Gutierres?”

“Unless he was trying to avoid oversight.”

Ezrin nodded again. “Go on.”

“He’s doing something he doesn’t want his bosses to know about.”

“It gives them deniability.”

“And . . . he’s got that tank of what he calls ‘special additives’ for the prisoner. I don’t know what that stuff is, but—” Manny slumped in his chair. “Christ. No wonder it wants to die.”

The colonel’s face remained stony, betraying no surprise, no incredulity.

“You knew, sir?” Manny said.

“I suspected.”

Manny thought he should be disgusted. Angry, even. All he could manage was weary resignation. This, on top of everything else. “What are we—”

“You’re going to keep your damned mouth shut, that’s what. You’re still detailed to Gilmore for a reason.”

“Sir?” Manny didn’t follow.

“In a few days, you’re going to get paged. You’ll be called to report to Beta Dome. Don’t question the page, don’t talk to anyone about it, just come. Alone. Got it?”

Before Manny could respond, the XO left, slamming the door behind him.

4.

The swelling in his ankle went down after a day. Manny continued with the pain meds, kept off it when he could, and adopted a shuffling limp when he could not.

Far worse than the ankle was the silence.

Since Quinn had pointed it out to him, he had become acutely aware of how thoroughly he was being shunned. People he passed in corridors, even those he had known for years, avoided eye contact. No one offered a hand to help him when he limped down a flight of stairs.

On his hobbling way to work one morning, a hand clapped him on the shoulder.

He turned. Gianelli and Keenes, a couple of poker buddies from the hangar bay, stood there. Gianelli was the shorter of the two—chubby build, round cheeks, a blond mustache dirtying his upper lip. Keenes stood tall, gaunt and pale, with sunken features and lifeless eyes that made him a formidable poker player. Gianelli said, “Nice swimming pool you made for that fish, Outhouse. When do we get to use it?”

Manny casually flipped him off. Gianelli and Keenes moved on without another word.

It was the most substantive conversation he had that day.

Even his Maggots got quiet whenever he was around. And Quinn, who at the very least should have been grateful that he had taken the hit for her, had inexplicably withdrawn again.

You very likely saved the prisoner’s life, Ezrin had said. If so, no one appeared ready to thank him for it. He had become something worse than persona non grata: he had ceased to even exist at Hargas Base, as if he personally had gone black—completely cut off.

He wondered how they would react if they knew what was really going on in the secured area.

As Manny had suspected, Gilmore was less than pleased that Manny was still on the job.

The Intel man insisted on confiscating Manny’s ID badge before allowing him back into the secured area. As Manny handed it over, Gilmore said, “You know, I thought I could trust you, Manny. Clearly, I cannot. You’re no better than any of the rest of them. Fine. You do your job, and stay the hell out of mine. Got that?”

Manny glared at Gilmore, but—remembering what Colonel Ezrin had said about being transparent as domeglass—said nothing. It occurred to him in that moment, somewhat belatedly, that he would now likely never get out from under General Levine’s thumb.

Security saw to getting him a replacement badge, one without access to the fire exit.

His bum ankle made the latrine unit harder to handle, but Manny managed. He had to hold his breath against the gagging stench of the Walphin’s effluent. The prisoner, as usual, made no move for the open trapdoor, keeping its distance whenever Manny came to empty the latrine. The blotches on its gray skin had become darker, unmistakable. Manny’s gaze often wandered to the additives tank whenever he was in the secured area.

On the fifth day following the incident, Manny sat at his desk, his foot propped on an open drawer, preparing month-end reports. The desk stood in the corner of what passed for office space in the treatment plant—a glassed-in area that overlooked the main floor, reachable by a single flight of stairs and through a door marked Administration. Water stains defaced the floor and ceiling. An ancient network server hummed in another corner. A break area, consisting of a couch and rickety coffee table, occupied the center of the room. Old requisition forms, a deck of cards and the pungent remains of someone’s lunch littered the table.

One of his Maggots entered—Johansen, a baby-faced blond giant who often needed to stoop when going through doorways. He was good with a cutting torch; he had made the hole for the observation window in the prisoner’s tank. “Wanted to see me, Sarge?”

“Yeah. Come on over.”

Johansen stopped behind Manny, looming. Manny looked up at him. “Jesus, sit down, will ya?”

“Sure, Sarge.” Johansen pulled up a spare chair.

Manny pointed to his monitor. “Are these numbers right?”

Johansen leaned forward for a better look. “That’s for this month? Yeah, they look right.”

“I don’t like the direction these impurity concentration levels are going.”

“They’re up, but they’re still within regs.”

“Sure they are. But we have our own standards down here, don’t we?”

“Right, Sarge.”

When he had gotten this job, Manny had implemented more stringent filtration benchmarks than provided for in the field manual. If they couldn’t keep reusing their water, Hargas Base would quickly run dry, ice mines or no. It was a message he constantly drummed into the heads of his Maggots.

“What’s happening out there?” Manny said.

Johansen shifted in his seat. “Well, Sarge . . . we’re, uh . . . we’re trying to keep up, but—”

“Just say it, Johansen.”

“We’ve lost some of our filtration capacity.”

“Tank Four, you mean.” The swimming pool, as Gianelli and Keenes had called it.

“Without Tank Four, we have to run wastewater through the other three tanks faster. We still trap the biggest solids, which is all primary sedimentation is supposed to do. But—”

“But we’re not catching as much as we used to.”

“We’re still within regs.”

Manny stared at the numbers, shaking his head.

Johansen said, “Sorry, Sarge. I know we’re letting you down. We all feel bad about it.”

“What?” Manny gently put his elevated foot on the floor and swiveled his chair around to face Johansen. “Who said I was blaming you guys?”

Johansen shrugged. “Well, I guess we just assumed. You’ve been pretty quiet lately. We figured you were mad at us.”

Manny marveled at his own stupidity. Had he really suspected his Maggots had turned against him? “Johansen, we’ve lost twenty-five percent of our primary sedimentation capacity. I’m not going to blame anyone in my unit for that. But if you knew the impurity concentrations were this high, you should have told me. Don’t just drop the numbers on me like this.”

Johansen lowered his gaze. “Right, Sarge.”

“Hey. Look at me.”

Johansen did.

“No one else on this base does what we do. No one else knows what it’s like. Not the Ag workers in the domes, not the miners, certainly not the officers. Without us, there wouldn’t be a base at all. We’re Maggots, and we’re proud of it. Right?”

“Maggots.” A faint smile touched Johansen’s face. “Yeah.”

Manny sat back. This whole business—the prisoner, Gilmore, being cut off—had screwed up his perceptions worse than he’d supposed. “So what else is the team saying?”

Johansen chuckled. “There’s so much talk, I don’t know where to start. Not just the team, but everywhere. It’s getting really weird out there.”

“Is everyone still worried about implanted bombs?”

“That one’s old news by now. The implanted homing beacon has gotten pretty popular, though. Any minute now, half the base is expecting Walphin warships to appear in orbit.”

So Quinn hadn’t kept it to herself, after all. Manny supposed he shouldn’t have been surprised.

“The newest one is the spookiest, though,” Johansen said.

“The newest one?”

“Biological warfare. They’re saying the fish is going to infect us all with some alien bug, or something.”

Manny went cold. “Perfect.”

“Some are even saying you’re probably infected.”

“Me?”

“From when it bit you.”

Manny pounded his desk with a fist. “It never bit me. I’ve never touched the damned thing. Jesus! How did—”

He stopped himself. He had a pretty good idea how it had gotten started. And the rumor would certainly explain some of the behavior he’d seen.

Johansen was right. It was getting weird out there.

“Do I look sick to you?” Manny said.

Johansen shrugged. “You look tired.”

“I am tired. But I’m not infected with anything.”

It was a good thing none of the rumormongers were able to see the prisoner. One glance at the Walphin in its current state would just confirm that it was sick. Manny had emptied the latrine that morning. The Walphin had looked terrible—gaunt, with pieces of dead skin hanging from its body. And the stuff coming out of the latrine had become even more foul. It had gone from dark to outright black. Where it had been oily, it had thickened to the consistency of molasses. The ultrafine filters in the vents were getting blocked with small chunks of solid matter that Manny didn’t even like to speculate about.

Johansen said, “What’s spooky is how serious people have gotten. The rec hall has gotten really . . . quiet. It’s the weirdest thing. There are all these little groups of people, and they’re all talking in whispers and looking around to make sure no one’s listening. I keep hearing that there are all these secret meetings going on. About what, I have no idea.”

Gone black, cut off from the rest of human space. Base discipline growing lax. And now, paranoia, secret meetings where people talked in whispers. Dark suspicions stirred in Manny.

“It’s good to talk about it,” Johansen said. “I don’t know what to do, Sarge.”

Manny leaned forward. “Listen to me. If you hear about anything else—anything you don’t like the sound of—I want you to come tell me about it. Come to my quarters if you have to, but make damned sure you find me. You don’t have to name names or rat anybody out. But if something bad is going down, I need to know about it. Will you do that for me?”

Johansen’s baby face went utterly solemn, aging him ten years in a moment. “Sarge, I need to ask you something.”

“Shoot.”

“Why did you save its life?”

Manny had been wondering that himself since it had happened. “Do you think I shouldn’t have?”

“Don’t know. Just asking.”

But of course that wasn’t true. “To be honest, there wasn’t any time to think it over. I just acted on instinct.”

Johansen glanced away.

“But I’ll tell you something: it was a human instinct. I don’t know that a Walphin would do the same for a human prisoner—if they took prisoners. And I don’t want to sink to that level.” It was the only answer he’d been able to come up with.

Johansen looked at him in much the same manner Ezrin had, studying his features as if for clues.

Transparent as domeglass, the Colonel had said. That wasn’t always a bad thing.

“If I hear anything strange, I’ll tell you,” Johansen said.

“All right. Thanks.” Manny clapped him on the shoulder. “Go ahead and get back to work.”

With a nod, Johansen stood and exited the office, heading back to the floor.

Manny’s comm sounded, startling him. He pulled it from his pocket. A simple, unsigned message scrolled across the display: Report to Beta Dome immediately.

Manny swallowed and acknowledged the page with the press of a button.

Beta, one of the smaller greenhouse domes, stood fifty meters across and ten meters high, filled with rows of soybean, lettuce and spinach plants, all in nutrient trays. It was truly the perfect growing environment: no weather, no pests, no weeds. The tinted domeglass was polarized to filter out UV from 47 Ursae Majoris. The ventilation system provided the carbon dioxide. And even here, Manny’s team had a hand; sludge from the treatment plant provided much of the nutrient.

The greenhouse domes were the very heart of Hargas Base. They proved to be popular locales, often attracting more visitors than the rec hall or even the sun dome. They were warm, for one thing, and usually very quiet, for another, making them ideal for relaxation and solitude. The air itself, charged with oxygen, invigorating, smelled of an earthiness not found anywhere else on base. If you closed your eyes and inhaled deeply, you could almost believe you were home.

As Manny entered, he could not help looking at the inky black sky. The yellow brilliance of 47 Ursae Majoris blazed high overhead, blotting out any chance to spot the JT in orbit. The image of a Walphin warship, loaded with weapons to turn Hargas Base into molten slag, came to him unbidden.

He hobbled over to Lieutenant Colonel Ezrin, who stood at the far side of the dome with his hands clasped behind his back, gazing out at the barren, gray-brown rock of 47UMaD.

“Colonel,” Manny said, and saluted.

Ezrin gave only the faintest of nods in reply, intent on the landscape. Hesitantly, Manny let the salute drop. He followed Ezrin’s gaze, but saw nothing out of the ordinary outside—craggy ridges, fissures, a nearby crater.

“Gutierres, sit before you fall over.”

“Yes, sir.” Manny deposited himself on a nearby bench.

Ezrin said, “I’ve always believed that what we do here, at this base, is one of the most honorable jobs a person can have in this army. It’s considered a shit assignment, I know, but I’ve never seen it that way. Not compared to what else is out there—paper pushing, empty strategizing, pointless public relations. Maybe you can understand that, Gutierres.”

Manny recalled what he had said to Johansen and nodded.

“Honor,” Ezrin said. “That’s what being a soldier is all about. And Mr. Gilmore has poisoned that, for all of us. It’s like an infection, and it’s spreading.”

Funny he should put it that way. “Speaking of infections, sir—”

“The alien virus rumor?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’ve heard it. The last thing we need around here. And it doesn’t help matters that the base is officially under quarantine.”

Manny glanced up sharply. “Beg pardon, Colonel?”

“It’s the cover story, Gutierres, the reason we’ve given for going black. Some of the enlisted learned of it. Then you had your little encounter with the prisoner. It made for quite the volatile combination.”

“Sir, I have reason to believe—”

With a flick of the wrist, Ezrin dropped something small into Manny’s lap. Manny picked it up. It was a blank ID badge, featureless white on both sides.

“You might want to try that badge sometime. You might find that it has the same access as the one Gilmore confiscated. It might be able to get you through the fire exit at the treatment plant without setting off the alarm. And take this, too.” He produced a tiny optical disk the size of a coin and held it out to Manny. “In case you were interested in Gilmore’s computer records, maybe.”

Manny’s brow puckered. “In case I were—” He stopped, recalling what Ezrin had said about deniability. He glanced at the blank ID badge. His breathing slowed. “Computer records. I would need Gilmore’s encryption key to access that stuff.”

“Really. Imagine that.” The faintest of smiles touched the corners of Ezrin’s mouth.

Manny gaped, thunderstruck. “Sir, how did you get that?”

“How did I get what?”

“The—right.” He took the disk, holding it between his thumb and forefinger. “But . . . what if I’m caught? I can’t exactly move fast.”

“Then don’t get caught.”

Manny had to stop himself from saying, Thanks a lot. Instead, he said, “What do you think I’ll find?”

“Leverage, Guiterres. Leverage.”

Manny looked from Ezrin to the tiny disk and back again. The entire situation suddenly felt unreal, dreamlike—or nightmarish. “All due respect, sir, but weren’t you the one who said I was as transparent as domeglass? Why are you trusting me with this?”

“Transparent though you may be, you understand about honor. You didn’t give up your friend, even when threatened with a court martial. And make no mistake, Gutierres: if I hadn’t intervened, that is most probably what would have happened to you.”

Manny’s cheeks burned.

“You’re just about the only person I trust on this base. I don’t need to tell you this, but I will, anyway: you and I are the only ones who are ever to know about this conversation.”

Manny drew in a long, shuddery breath. He pocketed the disk and the ID badge. “Yes, sir.”

Ezrin gazed out again at the landscape. “If you’re going to do . . . anything . . . it should be done as quickly as possible. Tonight.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Get back to the plant. It will raise questions if you’re gone for too long.”

“Colonel?”

Ezrin glanced at him.

“Sir, I . . . I don’t know exactly how to say this, but . . . I have reason to believe there’s going to be trouble. Some of the troops might be planning something.”

Ezrin waved it off. “Get the right leverage, and Gilmore and his pet will be gone tomorrow. This whole thing will be over with. Then maybe we can get back to doing our jobs around here.” He held out a hand, helped Manny to his feet.

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t screw this up, Gutierres. It’s the most important thing you’ll ever do.”

Manny swallowed hard, nodded. He left the colonel, hobbling back to the treatment plant. His gut felt like a stone.

He worked the rest of his shift in a daze, unable to focus on completing the month-end reports. He was grateful he wouldn’t have to see Gilmore before nightfall.

He finished his shift and headed back to quarters, rehearsing in his mind the steps he would have to take to get back into the secured area. The corridors seemed as empty as they had when Gilmore’s JT had first appeared in orbit. Every door was shut; no music or conversation wafted out from behind them. It was beyond weird; it was damned unnerving.

He let himself into his quarters, shut the door behind him and collapsed onto his couch, spent.

He must have dozed. His door chime awakened him.

He glanced at his clock; half an hour had passed. He shook his head to clear the fogginess and hauled himself off the couch, wondering who in the hell would be paying him a visit. Ezrin, perhaps, wanting to call it off.

It was Gianelli and Keenes—in better days, his two poker buddies from the hangar bay. Gianelli’s fat face split with a jocular smile. “Hey, Outhouse. What’s up?”

The two of them stepped inside, uninvited. Caught off guard, Manny backpedaled a step, eyeing them. “I was napping, I guess.”

“Oh. Damn. Sorry to wake you, man.”

“Yeah,” Keenes said. “You don’t have to stand on our account. Sit. Rest that ankle.”

Manny remained where he was. Keenes closed the door and stood in front of it; Gianelli sat at the kitchen table.

Manny said, “What are you two doing here?”

Gianelli shrugged. “Thought we’d stop by, see how you were doing. Got any beer?”

“I’m on barracks restriction. You guys know that. I can’t have any visitors.”

Keenes crossed his arms. “Yeah. Been a rough few weeks for you, hasn’t it?”

Manny tensed. “I think you two should leave.”

“Best if we stay, I think,” Gianelli said.

“Yeah,” Keenes said.

Neither of them made a move toward him. Keenes held his position; Gianelli got up and looked in Manny’s tiny refrigerator. “Boy, they were serious about that barracks restriction, weren’t they? Nothing but base rations in here.” He wrinkled his nose, shut the refrigerator and sat again at the kitchen table.

And Manny understood. “It’s going down tonight, isn’t it?”

“Don’t know what you’re talking about, Outhouse,” Gianelli said. “Do we, Keenes?”

The tall man shook his head. “Not at all.”

“You two are supposed to keep me here, right?”

“Where would you go?” Gianelli said. “You’re confined to quarters. And you know, that’s probably for the best. Things have gotten awfully strange around here lately.”

“Awfully strange,” Keenes said. “Sit down, Outhouse. You’re not going anywhere tonight.”

They passed an hour in silence. Manny sat on the couch. Keenes eventually came away from the door and joined him there. He pulled out a handheld and flipped through screenfuls of text, catching up on some reading. Gianelli remained at the kitchen table, playing solitaire with a deck of cards he’d brought with him, occasionally snacking on Manny’s rations. He held out a packet to Manny, who declined with a shake of the head.

Manny considered and discarded various ways of escaping, idly fingering the ID badge and disk Ezrin had given him, still in his pocket. With his bad ankle, he could not make a run for the door. He could try threatening to rat the two of them out, but that would be an empty gesture, and they would know it. Gianelli and Keenes would simply deny they had ever been here tonight, and they would undoubtedly have a dozen compatriots willing to back their story. Manny would have only his word, and a reputation that had taken a pounding of late.

The rest of the co-conspirators, whoever they were, would be similarly covered. As long as everyone involved took reasonable precautions to leave behind no evidence, and as long as they all stuck to the same story, no one could be arrested or indicted.

And still, the Walphin would be dead before dawn.

Manny hoped they would get it over with soon. This waiting, this sense of utter helplessness, was its own kind of torture.

He hated to admit it, but the operation bore the marks of Quinn’s organizational skills—simple, coordinated, efficient.

Manny broke the silence, wondering aloud more than making conversation: “How is she planning to get past Gilmore’s guards? She surely doesn’t want to start shooting at them. That’s a whole different kind of trouble.”

Keenes didn’t even look up from his reading. “Don’t know who you’re talking about.”

Gianelli gathered his cards again and shuffled. “You sure you’re OK, Outhouse? You look a little piqued. A little sick, even.”

Manny narrowed his eyes. “I’m not sick, except of your face, Gianelli.”

“You sure that’s all it is? You sure you haven’t picked up something from that fish?”

“I’m sure.”

“Yeah? Do you suppose that Intel man would tell you if you had? Do you think he’d tell anyone?”

“That’s paranoid bullshit.”

“This base is quarantined. Did you know that? Are you gonna tell me that’s paranoid bullshit?”

Manny fell silent. No point in arguing. These two had already made up their minds.

Pounding at the door startled all three of them. As one, Gianelli and Keenes turned to Manny.

Wide-eyed, Gianelli said, “You expecting someone?”

Manny shook his head, as baffled as they were.

More pounding. A muffled voice came from the other side of the door: “Gianelli! Open up! Hurry! Something’s gone wrong.”

Gianelli was on his feet in a flash. He crossed the room with more speed than Manny would have given him credit for.

He pulled it open. “What the—”

He uttered an oof and went staggering backward, doubled over and clutching his ample gut. His feet tangled and he fell.

Keenes ran for the door. Someone on the other side grabbed him and pulled him into the corridor. Manny heard a crash that shook the walls.

Johansen came through the door, hands balled into fists, his attention on Gianelli.

The fat man was still on the floor, gasping. The wind had been knocked out of him. He scrabbled away from Johansen.

Johansen turned to Manny. “Come on, Sarge. We have to hurry.” He helped Manny to his feet, moved for the door.

“Wait,” Manny said. “Get their comms. We can’t have them calling for help.” It would buy only a few minutes, but judging from Johansen’s urgency, that was all the time they had, anyway.

“Right.” Johansen went to Gianelli, crouched. Gianelli thrashed and kicked. One look at Johansen’s face, though, and he went still.

Johansen grabbed the comm clipped to Gianelli’s belt and pocketed it. He looked up at Manny. “What about yours?”

“Right here.” Manny had it with him, clipped like Gianelli’s.

The two of them went into the corridor. Keenes lay in a heap against the opposite wall, unmoving. Johansen got his comm, too.

Only then did Manny notice the motorized cart, like the ones used in the mines, in the middle of the hallway. Johansen nodded toward it. “Get in. You can’t run.”

The carts weren’t built for speed, but would certainly be faster than Manny on foot. They got in. Johansen thumbed a stud, and the motor whined into humming life. Using the control sticks, he backed the cart, turned it and then headed down the corridor, in the direction of the treatment plant.

Johansen said, “I was having a drink with one of the cargo loaders from the hangar bay. He slipped up, let me know what was going on.” He looked at Manny. “You said you wanted to know, right?”

Manny nodded.

“We have to hurry. They’re going to trigger the fire alarm to draw the guards away from the secured area. Then they’ll move in and—”

“How many of them are there?”

“I don’t know. Seems like half the base is in on it. That cargo loader just assumed I was, too. I guess he forgot that I was a Maggot.” He steered the car around a bend and flashed a grim smile.

Half the base. Jesus. “We need to call in the MPs.”

“Can’t. Some of them are part of this. I don’t know which ones to trust.”

Manny dug out his comm. “Colonel Ezrin, then.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeah.” He powered up the unit, and waited for the ready indicator to light. It seemed to take forever. His hands shook.

Johansen took another corner at full speed, causing Manny to grab hold of his seat, lest he fall out. They were passing the rec hall now. It was empty and dark.

“Sarge?” Johansen kept his attention on what he was doing, but his tone had gone strangely soft, even pleading. “I’m a private that just assaulted two superiors. I knocked one of them unconscious.”

“Nothing’s going to happen to you. Those two would have a hard time explaining what they were doing in my quarters.”

Manny raised the comm and punched in Ezrin’s code.

Just then, sirens began to wail from the PA, echoing throughout the corridor.

Manny and Johansen exchanged glances. Someone had tripped the fire alarm.

“Oh, Christ,” Manny said.

5.

Ezrin didn’t answer his comm. No doubt the fire alarm had gotten his full attention. Disgusted, Manny flung his comm away as they sped through the corridors.

They pulled the cart into an elevator; it barely fit. Manny reached back and punched the button for the maintenance sublevel. The doors closed and they descended. The sirens continued wailing, even in the elevator.

Too long. It was all taking too long. Despair settled over Manny. No way they would make it in time. It was probably over with already.

The elevator slowed, stopped. The doors opened. Johansen backed out the cart, jerkily, and headed for the treatment plant.

The level smelled of smoke; a vague haze hung in the air. Johansen looked at Manny, eyes wide.

“Not just a false alarm,” Manny said. “They set a real fire somewhere on this level.” That made sense. A false alarm would be too quickly settled; a real one would take longer and create a much bigger distraction.

They came to the T-junction and turned right. The haze was thicker here, stinging Manny’s eyes. Men in bright orange Fire Crew uniforms, carrying suppression packs slung over their shoulders, ran toward them. Manny braced himself for a fight, but they went past without a second glance.

The doors to the treatment plant’s main floor stood wide open. Johansen barreled through them without slowing. Johansen wound past Tanks One, Two and Three, jockeying around and under pipes. The partitions that marked the boundary of the secured area stood twenty meters ahead. Gilmore’s guards were nowhere in sight.

“Shit,” Manny said.

The fire alarm wailed on and on.

The entryway was too narrow for the cart. Johansen braked. The hard rubber tires squeaked as the cart stopped with a jolt. They got out. Johansen hesitated, looked back at Manny.

“Just go,” Manny said. “Now.”

Johansen bolted.

Raised voices, inarticulate shouts floated back to Manny. He went into a rapid limp-hop, wincing at flaring pain in his ankle.

A crowd of enlisted, split into two distinct groups, had gathered in front of Tank Four. None wore Fire Crew uniforms. Johansen was yelling at a hulking monster of a man, a few inches shorter than Johansen but with broader shoulders and chest, great thick arms and fists the size of melons.

They all turned to Manny as he approached. The shouts died away. The incessant siren blared and echoed.

Manny took only a second to piece together what had happened.

A line of his own people, his Maggots, four in all, had formed a small barricade in front of Tank Four. He recognized them as the treatment plant’s graveyard shift. The rest was easy to figure out: true to their training, the graveyard crew had stayed on the job even when the fire alarms had sounded, and had seen the would-be assassins entering the secured area, even as Gilmore’s guards had run off to check on the fire.

The miniature lynch mob, a half dozen of them, had been balked—so far.

Manny looked over them. Most he recognized. Some were veterans, some greenhorns. One was even an MP. They all carried pulse rifles—except for the big one getting in Johansen’s face. His lay at his feet. He apparently had been willing to go man-to-man with Johansen.

So, then—the numbers were even, except for the rifles. The Maggots didn’t even have sidearms.

Tank Four loomed behind the tableau. Manny only glanced at it. He stopped, panting hard. He took a moment to regain his breath, then said, “Where’s the fire?”

Members of the lynch mob exchanged glances. A couple of them moved aside, and Manny saw they had a seventh with them—Quinn.

She bore no weapon as she came forward, head held high, calm, as if in no hurry at all.

“It’s in Sanitation,” she said. “In one of the refuse bins. It’ll burn nicely, but it’s safely contained. And it will give Gilmore’s guards a good excuse for leaving their posts.”

“The guards? They’re in on it, too?”

“Don’t worry about it. Tell your people to stand down, Manny. Right now.” She nodded to her compatriots. They turned to the Maggot barricade, raised their rifles.

“No,” Manny said. “It’s already over, Resa. Your cover’s blown. Tell your people to stand down.”

“I don’t want to hurt you or anyone else, Manny. But I will if you stand in my way.”

“This won’t bring them back—your brother and his family. And the prisoner didn’t take them from you.”

Her lip curled. “That prisoner is endangering everyone on this base. But it’s not so bad, not so tough. You showed me that. So we’re going to take care of this. Now stand down. Last warning.”

Manny looked at Johansen, and the rest of his Maggots. They looked back, awaiting his word, his leadership. They would do whatever he told them to do, even if it meant risking their lives. In other circumstances, he would have swelled with pride at the thought. That damned sense of duty of his—it had caused him to be exiled to Hargas Base, it had alienated him from his friends, and now it had him and five of his subordinates staring down the barrels of pulse rifles.

Manny hobbled over to the graveyard crew. Johansen followed. Taking a deep breath, Manny joined them in their line, facing down Quinn and her people. Johansen stood at Manny’s shoulder.

Manny said, “You know what? The war has finally come to us. Now we’re all on the front line. And it’s not so easy to choose anymore. Not so easy to know what the right thing is.”

Quinn’s hands trembled. “Goddamn you, Manny. How can you betray your own people like this?”

“I’m not sure which one of us is the traitor, Resa. You guys are the ones with the guns. What do you say? You want to show the Walphins that you can be just as ruthless as they are?”

The sirens cut off. Manny’s ears rang in the sudden silence.

Members of Quinn’s crew glanced up and around, blinking as if they’d just been awakened.

“Time’s up, Resa,” Manny said. “If you’re going to do it, you have to do it now. Or never.”

Her breathing became heavier. “Don’t, Manny. Don’t . . . make me do this. Because I will. You think I won’t?”

“Honest to God, I don’t know. But it’s your choice.”

The moment stopped, held. Some remote part of Manny’s mind registered the smoke in the air, the way it stung his eyes, the rancid, burnt smell. They might be among the last things he remembered in this life. But he would not take his gaze off Quinn, even if she had him shot. He would die looking her in the eyes. If nothing else, he would make certain of that.

Her trembling became more pronounced, her breathing progressively louder with every passing second, as if she were working her way around to the scream that would be his death sentence. Her mouth moved soundlessly.

A single tear slid down one cheek, fell to the floor.

Noises from outside filtered back to them—confused shouts, slamming doors, boots tramping down corridors. Coming nearer.

A faint sound escaped Quinn’s throat. The assassins glanced uneasily at her.

“I—” Quinn swayed on her feet, staggered. The big brute caught her before she fell, holding her by the shoulders. She muttered something. Manny only caught some of her words. He thought she may have been apologizing to her dead brother.

The other assassins looked to her, slowly lowered their rifles. Confused scowls creased their features.

Manny said to the brute, “Get her out of here. Quick. Use the rear exit.” He proffered the badge Ezrin had given him. “This will get you out without setting off the alarm again. Take her back to her quarters. Do it, and none of this happened. Understood?”

The brute hesitated, then took the badge. To the others, he said, “Come on.”

One of the other assassins said, “We can’t—”

“Come on.” The brute spoke through clenched teeth. He led Quinn toward the fire door, moving quickly. The rest followed in haste, some eyeing Manny and his Maggots as they passed, others looking at the tank with stony expressions. None of them noticed the pulse rifle, gleaming in dull black, left on the treatment floor. Careless.

Then the lynch mob was gone.

The Maggots literally breathed a collective sigh of relief, all of them exhaling at once. Two of the graveyard crew members embraced. Johansen said, “Oh, God. Oh, God.”

Manny said, “Lock this plant down. Right now. Before Gilmore’s guards come back. No one else gets in here. I don’t care who’s outside the doors. Understand me? No one else gets in.”

They gaped at him, motionless, uncomprehending. Johansen said, “Uh, Sarge . . . I—”

“This isn’t over yet. Now move.”

“Exactly what isn’t over yet?”

All of them turned in the direction of the voice. Gilmore stood in the entryway, hair mussed, dressed only in a dark robe, rumpled sleepsuit bottoms, and slippers. He stepped in, frowning, looking around. “Manny? What’s going on here? Where are my guards?”

The others exchanged guilty glances, but Manny remained composed—outwardly, anyway. “Not as trustworthy as you’d like to think, I guess. Good thing my people were here.”

Gilmore glanced over his shoulder at the entryway, then back at Manny, then at the pulse rifle on the floor. He sniffed the air. Understanding dawned in his face. He rushed to the tank, peered through the observation window.

“The prisoner’s—” Manny started to say fine, but stopped himself, realizing how stupid that sounded. What could he say? Safe? All right? Unhurt? None of that was true. “It’s still alive.”

Still looking through the window, Gilmore said, “I want everyone out of this area. Now.”

The Maggots looked to Manny. He nodded at them. “Go ahead. Lock down the plant, like I told you.”

Johansen opened his mouth to say something, then thought the better of it. The team shuffled out, leaving Manny and Gilmore alone.

Almost.

Manny hobbled over to the pulse rifle lying on the floor and stood over it.

Gilmore pulled his gaze away from the window. “I knew it was getting bad, but I didn’t realize how bad. Manny, you’ve done an extraordinary thing here. I want you to know how grateful I am for this. Fill out another transfer application, and this time, send it to me. I will personally see to it that it goes through.”

Manny winced. Just like that, there it was, right in front of him again. His for the taking. Ezrin would be disappointed, but what of it? Manny would be gone, Hargas Base forever behind him.

Except that he had just risked his life and lives of his Maggots, and he hadn’t done it for Gilmore.

“Tell me something, Mr. Gilmore: what’s in that special additives tank?”

Gilmore’s gaze flickered in that direction. “I told you. It’s for the prisoner.”

Manny shook his head, bent to retrieve the pulse rifle at his feet. He pointed it at Gilmore.

The Intel man took a step backward. “Manny? What are you doing?”

“I know what’s going on here. Whatever you’ve been poisoning the prisoner with, it ends tonight.”

“No. You have it all wrong, Manny.”

“Oh, I don’t think so.”

Gilmore licked his lips. “You don’t understand, Manny. Without that”—he pointed to the additives tank—“the prisoner couldn’t survive. Walphin digestion . . . it’s dependent on tiny, acid-secreting symbiotes. That’s what in this tank. The symbiotes require a delicate temperature balance and a steady stream of nutrients. Easy enough to find in the Walphin digestive tract, harder to do outside of it.”

Manny looked at the milky water. Acid-secreting symbiotes—it actually sounded plausible. Except . . .

Except the Walphin hadn’t been digesting anything very well lately. Manny had seen the evidence firsthand. His stomach roiled. “You sadistic bastard. You’ve been withholding those symbiotes, haven’t you?”

Gilmore gulped. Manny could see his throat working from across the room.

He tried to imagine it: eating would have become extremely painful for the Walphin, tearing into its gut, getting worse every day. Probably some internal hemorrhaging, too. Eventually, it would have stopped eating altogether. And all the while, Gilmore continued beaming his questions at it: Where? When? How many? And perhaps the occasional Tell me what I need to know, and I’ll make it stop hurting.

Quinn had said, Nobody here is a fan of Intel Branch. Those jackasses haven’t produced any useful intelligence since the war started.

The Walphins had gone quiet on all major fronts.

And the prisoner hadn’t been cooperating—the highest-ranking Walphin ever captured.

Gilmore was breathing fast. “Manny, the next attack could be coming any day now. Don’t you understand? We don’t have time to ask politely. That prisoner isn’t a human being. It’s not entitled to human rights.”

“You’re a son of a bitch, you know that? You used us. You used this whole base as a cover. I think I had more respect for the lynch mob.” Manny raised the rifle, sighted. “Get out.”

“Manny, think about what you’re doing. If I turn around and walk out of here, you’ll never see Earth again.”

His father’s face came to him. The barrel of the pulse rifle wavered.

“Put that thing down,” Gilmore said, “and we can forget about all this.”