‘Nine weeks? Nine weeks, on a ship?’ Gozo gave a high-pitched yelp.

Jacques le Grand rolled his eyes. The old man at the bazaar was right, Gozo really was excitable.

‘You’re crazy, Mr Bartlett! Listen, each day we load the melidrops on the wagon at four in the morning. By seven o’clock, eight at the latest if there are lots of wagons on the road, I deliver them to the old man at the bazaar. He sells them all day and closes his stall in the evening. And the next morning, before I get there, do you know what he does? He spends an hour throwing out all the ones that are left over from the day before! They’re already starting to rot. And you want to take them for nine weeks! Nine weeks, that’s … sixty … sixty …’

‘Sixty-three days.’

‘Sixty-three days! Right. I would have worked it out if you’d given me another minute.’ Gozo shook his head, muttering to himself about ships and weeks and sixty-three days, and crazy men called Bartlett. ‘Mr Bartlett, you should stop wasting your time. I’m sure there’s a ship that can take you home. You’ve probably got little children who are missing you.’

Bartlett laughed. ‘Gozo,’ he said, ‘I like you.’

Gozo waved an arm. ‘Doesn’t matter whether you like me, Mr Bartlett. Doesn’t matter at all. You’re still wasting your time.’ And with that Gozo flicked the reins that he was holding, as if to tell his horses what a ridiculous request these two strangers were making.

They had found him at the well outside the north gate, just as the old man at the bazaar had told them. He was lying fast asleep on his wagon in the shade of a tree. A straw hat covered his face. There were at least ten other wagons there as well, each with a sleeping driver. Gozo was the smallest one, no more than a boy. When he woke up and took the hat off his face he didn’t look old enough to be driving a wagon. His black hair stood up in spikes, and he had a little upturned nose which made him look even younger.

His uncle, Mordi, had a melidrop farm, and during the melidrop season it was Gozo’s job to bring the fruit to the bazaar each morning, except Tuesdays, when the bazaar was closed. On Tuesdays he went home to visit his mother. The wagon he drove was big and creaky, with two shaggy horses to pull it. That was the way to transport melidrops, he said. They could come and see for themselves, if they liked. Gozo put on his hat and picked up the reins. Normally he slept for another couple of hours, but he was already awake, and the day wasn’t too hot, and the horses had rested. So Bartlett and Jacques climbed up, dwarfing the little driver between them, and they set off.

They left the well behind. Soon there were rice fields on either side of the road. The bright green of the rice stalks shimmered in pools of water. The road was a narrow track of dazzling white dust. When two wagons crossed, they had to pull to the side and scrape past one another, teetering over the ditches on either side of the road. But Gozo was a skillful driver, and the wagon was always safe.

He drove with his eyes on the road, shoulders hunched, which made him look even smaller than he was. Gradually, remembering the warning of the old man in the bazaar, Bartlett began to question him about transporting melidrops. A wagon could take a melidrop eighteen miles, a rider on a fast horse could take it sixty, maybe eighty miles in a day. And how could you take it for nine weeks on a ship? That was when Gozo’s head jerked up and he yelped excitedly.

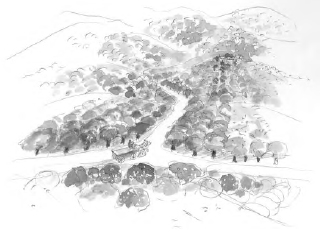

It took most of the afternoon to reach Gozo’s uncle’s farm. The horses walked slowly, having pulled a huge load in the morning, and Gozo didn’t hurry them. Jacques le Grand fell asleep and his chin bounced on his chest in time with the wagon’s motion. After a while the road left the flat plain and passed between rolling hills, and there were rows of trees instead of rice fields around them. The trees were low, with spreading branches and bright fruit peeping out amongst dark leaves: melidrop orchards. Eventually Gozo turned off the road and took the wagon down an even narrower track, deep into the trees. Branches scraped against the sides of the wagon. They drew up into a yard. There was a farmhouse, a stable, a barn, and on every side there were the dark leaves and bright fruit of melidrop trees.

The yard was empty. The farmhouse was long and low, and all the shutters were closed. Gozo jumped down and began to unharness one of the horses from the wagon. Jacques le Grand went over to a well near the corner of the farmhouse. He pulled up a bucket of water and drank thirstily. Then he gave the bucket to Bartlett, who tossed it into the well and drew it up again. The door of the farmhouse opened.

A tall man appeared. He had a big bushy beard frizzled with grey. His hair was standing in all directions, as if he had just woken up. He wasn’t wearing a shirt, and the pockets on his old trousers were peeling off.

‘Uncle Mordi!’ cried Gozo, looking up from the harness.

‘What’s this, have you brought help for the harvesting?’ said the man, walking to the well. He glanced at Bartlett and Jacques. Then he picked up a drinking mug that was on the ground beside the well, rinsed it, and filled it with water. He held the mug out to Bartlett.

‘Do you need help with the harvesting?’ asked Bartlett, taking the mug.

‘We always need help.’

‘They don’t want to help with the harvesting. You won’t believe what they want!’ shouted Gozo, leading one of the horses into the stable.

‘I won’t believe it?’ said the man, as much to himself as to Bartlett.

Bartlett drained the mug. The water was cool, pure and refreshing. He drank a second mugful.

In the meantime, the man had picked up the bucket and tipped it over his head. ‘Aah!’ he cried, as the cold water splashed his hair and ran down his back. He skipped and danced on the spot. He shook his head and waved his arms and sprayed water in all directions. ‘I love it. Cold water. I love it!’ he cried, skipping and slapping his chest with his fists.

‘They want to transport melidrops,’ shouted Gozo, coming out of the stable to get the second horse.

The man gave one last shiver and peered at Bartlett again. He glanced at Jacques le Grand. Drops of water stuck in his beard like glistening berries in a bush.

‘You need a wagon,’ he said.

‘No,’ shouted Gozo, ‘they don’t want a wagon.’

‘Then what do they want?’ the man shouted back.

‘Ask Bartlett,’ shouted Gozo, taking the second horse away.

‘Bartlett?’

‘Yes,’ said Bartlett. ‘That’s me. And this is my friend, Jacques le Grand.’

Jacques nodded.

‘Well, I’m Mordi,’ said the man with the bushy beard. ‘Welcome to my farm. You know, if you want to transport melidrops the best way really is a wagon. It’s very safe, and there’s hardly ever—’

‘They don’t want a wagon! ’ shouted Gozo, tearing out of the stable, ‘I’ve told you already.’

‘Nonsense, Gozo!’

‘No,’ said Bartlett, ‘he’s right.’

‘See, Uncle Mo, you never believe me!’ Gozo glared at his uncle with his hands on his hips. He barely came up to Mordi’s chest.

Mordi looked down at him. ‘What do they want, Gozo?’

‘You’ll never believe it, Uncle Mo.’

‘What?’ whispered Mordi.

‘Tell him, Mr Bartlett,’ said Gozo.

‘We want to transport a melidrop—’

‘For nine weeks, on a ship!’ Gozo blurted out.

‘No!’ said Mordi.

‘Yes!’ said Gozo, jumping up and down on the spot. ‘Yes yes yes yes yes!’

Mordi gazed doubtfully at Bartlett. ‘Do you? Really?’ Bartlett nodded.

Mordi glanced at Jacques le Grand to see if it was a joke, but Jacques nodded as well. Mordi frowned for a second. Then his face creased and he began to laugh. The laughter boomed out of his beard, big rolling waves of it, to spread between the melidrop trees in his orchard.