III. The Making of a Book: The Platform Sutra

BY THE END of the eighth century the Ch’an legend that was to persist had been established. The Pao-lin chuan, written in 801, had adjusted the list of the twenty-eight Patriarchs, presenting them in an acceptable form, and had helped to solidify the legend of Hui-neng. The version of Ch’an it furnished was, of course, not adopted at once, nor did variant legends simply die out when the Pao-lin chuan was written, but because the later Ch’an histories followed its theories, the story it presented came eventually to be the official one. But while the legend was, by the beginning of the ninth century, cast in a form that was destined to endure, the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch was still in the initial stages of its evolution.

The earliest version extant is the manuscript text discovered at Tun-huang.1 Concerning this manuscript several obvious generalizations can be made: it is highly corrupt, filled with errors, miscopyings, lacunae, superfluous passages and repetitions, inconsistencies, almost every conceivable kind of mistake. The manuscript itself, then, must be a copy, written hurriedly, perhaps even taken down by ear, of an earlier, probably itself imperfect, version of the Platform Sutra. What this earlier version was like we have no way of knowing. There have been two major theories concerning it. One, maintained by Professor Ui and followed by a great number of writers in Japan, presupposes an original version of the Platform Sutra, completed about 714, the year following Hui-neng’s death, consisting of the Master’s sayings, as recorded by his disciple Fa-hai. Through the years this version was added to, probably by men of Shen-hui’s school, until the text as we have it today was completed, probably around the year 820. The other interpretation, advanced by Hu Shih, while recognizing that the Tun-huang text is a copy of an earlier version, asserts that it is a product of Shen-hui’s school, and that any attribution to Hui-neng or Fa-hai cannot be justified. There is no way of resolving these two conflicting opinions, for the Platform Sutra, as we have it, does not furnish sufficient information on which to base a conclusive judgment. We can, however, make certain observations about the text itself which, although they do not solve the problems created by the obscurity of its origin, may indicate why these problems cannot be solved.

The Tun-huang manuscript is not dated, but judging from its calligraphic style, it was written sometime between 830 and 860.2 On the basis of the kinds of errors present in the manuscript itself, there can be no question that the work is a copy of an earlier version, written probably around 820. Section 55 of the present text contains a list of priests in the temple at Ts’ao-ch’i. It reads: “The Platform Sutra was compiled by the head monk Fa-hai, who at his death entrusted it to his fellow student Tao-ts’an. After Tao-ts’nn died it was assigned to his disciple Wu-chen. Wu-chen resides at the Fa-hsing Temple at Mt. Ts’ao-ch’i in Ling-nan, and as of now he is transmitting the Dharma.” If we are to trust this statement, it would indicate that Wu-chen was at least two generations after Hui-neng. However, the two Northern Sung versions of the Platform Sutra3 contain similar lists which indicate that Wu-chen was actually four generations after Hui-neng.4 Thus we are immediately faced with a contradiction between the two versions of the text. These Northern Sung editions of the Platform Sutra will be discussed later, but all indications show that they are more reliable and represent more accurate versions of the text than does the Tun-huang manuscript. It is difficult to approximate the length of a generation in the Ch’nn priesthood, but if we compare the lineage of other schools who claim Hui-neng as their Patriarch, we find that the fourth generation flourished during the second decade of the ninth century.5 One further item serves to confirm the year 820 as a fair approximation of the date of the Platform Sutra. This is the inscription by Wei Ch’u-hou, discussed below,6 which mentions the Platform Sutra by name. This inscription dates, in all probability, somewhere between 818 and 828.

The manuscript itself represents a transmitted text; in other words, as seen from section 47, possession of a written copy of the text served as an indication that the possessor had satisfied his teacher as to his understanding of the teaching. Whether the Platform Sutra was used in this way among Ch’nn schools other than the one that claimed descent from Fa-hai and had its headquarters at the Fa-hsing Temple, cannot be determined. Just as the transmission of the robe and bowl was symbolic of the handing down of the teaching up to the time of Hui-neng, and later in the Pao-lin chuan the transmission verse was emphasized, so we have here the use of the work itself to serve as proof that a person was a legitimate possessor of the teaching. It is therefore possible to assume that several copies of a text similar to the Tun-huang manuscript were at one time in circulation. Further evidence that other copies were extant at this time can be seen from the lists of books brought back by Japanese priests: it is found in Ennin’s catalog of 847,7 and in Enchin’s lists of 854,8 857,9 and 859.10 In addition, the contemporary Chinese scholar, Hsiang Ta, mentions having seen a copy of the work in the hands of a private collector during a visit to Tun-huang.11

The title of the Tun-huang text of the Platform Sutra: “Southern School Doctrine, Supreme Mahāyāna Great Perfection of Wisdom: the Platform Sutra preached by the Sixth Patriarch Hui-neng at the Ta-fan Temple in Shao-chou,” is highly elaborate, as is the title to the text brought back by Ennin in 847. It would indicate that at the time these two copies were made the text had yet to attain to the sophistication of a succinct and uninvolved title, or else that they were copied from primitive versions of the text.

An analysis of the contents of the Tun-huang text, in an attempt to determine which sections might represent a presumed original version, leads to rather inconclusive results.12 The most that can be hoped for is a characterization of some of the material contained. It may be classified roughly into five types: (1) the autobiographical material, (2) sermons, (3) material designed to condemn Northern Ch’an and elevate the Southern school,13 (4) those sections relating to Fa-hai and his school and those emphasizing that the Platform Sutra was a transmitted text, and (5) verses, miscellaneous stories, and other materials not included in the previous classifications.

Sections 2 to 11 contain the fictionalized autobiography of Huineng, and tell how the understanding of the illiterate Hui-neng triumphed over the Ch’an accomplishments of the head monk Shen-hsiu. The autobiography deals with the period from Hui-neng’s birth until shortly after he was made the Sixth Patriarch and returned to the south. Contained are the famous verses of Shen-hsiu and Hui-neng, indicative of the degree of understanding each had attained (secs. 6–8). These sections, while recounting Hui-neng’s life, also represent an attack on Shen-hsiu, as representative of Northern Ch’an.

Sections 12–31 and 34–37 contain sermons supposedly preached by Hui-neng at the Ta-fan Temple. This temple, however, has never been identified.14 In examining the sermons one is struck at once by the obvious parallels with the works of Shen-hui.15 Not only is there a similarity in the thought and concepts, but the wording is in some instances almost identical. The identity of meditation and wisdom found in section 13 is discussed in virtually the same terms in the works of Shen-hui; section 14 contains a reference to Vimalakīrti and Śāriputra, which is also found in Shen-hui’s writings; section 15 includes a passage on the lamp and its light, similarly included in Shen-hui’s sayings. The discussion of the concept of no-thought in section 17, the passage concerning the Mahāprajñāpāramitā in section 26, and parts of sections 30 and 31 all are paralleled in the works of Shen-hui. This is also true of the story of Bodhidharma and Emperor Wu of Liang found in section 34.

Because of the above similarities any attempt to define the “thought” of Hui-neng in the light of these sermons would not appear possible. We have seen, in addition, that Shen-hui, in his recorded sayings, at no time quotes from Hui-neng. Thus, even if we refrain from declaring that the thought of the Platform Sutra is derivative from the works of Shen-hui, we are at least obliged to admit that they parallel each other closely. The Platform Sutra contains much that can be described as general Buddhist teaching, such as discourses on the threefold body and the four vows; it has much material which, as with Shen-hui’s sayings, is based on the Prajñāpāramitā concept of mind. Quotations from various sutras show the influence that these works had on the Platform Sutra, but the same sutras are used by Shen-hui. The emphasis on such concepts as the identity of prajñā and dhyāna, sudden awakening, seeing into one’s own nature, of no-thought and no-mind, which are of fundamental importance in Ch’an, are to a degree new, but they are still to be found in Shen-hui’s writings. Through the agency of later editions of the Platform Sutra, some of these concepts are strengthened and developed; in a sense they are traceable to the Tun-huang edition, but several writers who have attempted to discuss the “thought” of Huineng lay particular emphasis on concepts which are not to be found in the earliest edition of the Platform Sutra. Thus Suzuki states: “What distinguishes Hui-neng most conspicuously and characteristically from his predecessors as well as from his contemporaries is his doctrine of ‘hon-rai mu-ichi-motsu’ (pen-lai wu-i-wu) . . . ‘from the first not a thing is’—this was the first proclamation made by Hui-neng. It is a bomb thrown into the camp of Shen-hsiu and his predecessors.”16 Yet it is quite certain that this doctrine was never pronounced by Hui-neng, for it is not found in the Tun-huang edition, and does not make its appearance until the Sung dynasty version.17 Other writers have laid emphasis on a passage from the Diamond Sutra, which is said to have occasioned Hui-neng’s enlightenment; but this passage, too, is not contained in the Tun-huang version of the Platform Sutra, appearing first in the Sung versions.18 For this reason, it would appear best to consider the Ch’an thought found in these sermons of Hui-neng as representing, together with Shen-hui’s writings, middle and late eighth-century concepts, which later Ch’an Masters organized, adjusted, clarified, and enlarged upon. But as the Platform Sutra was edited and corrected, its contents were still interpreted as representing the true sayings of the Sixth Patriarch. In other words, the legend is still at work, still developing, this time within the framework of the later versions of the book which purports to convey the sayings of the Sixth Patriarch.

Among those sections which are concerned with extolling the Southern school at the expense of the Northern, we find, in addition to the autobiographical sections, section 37 which, although it does not specifically mention Northern Ch’an, details a bit of Hui-neng’s biography, and describes the awe in which he was held by the assembled monks. Section 39 is a direct attack on the gradual teaching of Northern Ch’an. Sections 40–41 tell the story of Chih-ch’eng, who came as a spy from Shen-hsiu, of his conversion, and of his explanation of the Northern teaching and Hui-neng’s answer to it. Section 48 extols the understanding of Shen-hui, at the expense of the Master’s other disciples, including Fa-hai. Section 49 includes the prediction: “twenty years after I die some one will come forward to fix the correct and false in Buddhism.” This is a direct reference to Shen-hui’s attacks on Northern Ch’an, and proves that this section of the work was added by men of Shen-hui’s school.

The sections which are attributable to Fa-hai and his followers are chiefly those which insist that proof of the understanding of the teaching lies in the possession of a copy of the Platform Sutra, namely sections 1, 32, 38, 47, and 55 through 57.19 Of these sections, only section 1 fits in to any extent with the rest of the text, and it may well be that the last few phrases, which speak of the transmission of the teaching and the need to take the Platform Sutra as the authority, are later additions. Section 32 cautions against the reckless spreading of the teaching, especially among those who are not ready to receive it. It does not specifically mention the transmission of the text, however, and it may well be that the attribution of this section to Fa-hai’ school is inappropriate. Sections 38 and 47 deal specifically with the transmission of the text and section 55 with the handing down of the teaching, enumerating the names of the priests who have inherited it. Sections 56 and 57 are so corrupt that they are virtually unintelligible: they deal with the transmission and refer specifically to Fa-hai. These two sections are not to be found in any of the later editions of the text.

The remaining sections, which represent miscellaneous additions to the text, contribute little to our knowledge of the work. Section 32, containing the “formless verse,” is in all probability a later accretion. The verse, purportedly by Hui-neng, contains the term “ta-shih,” which certainly would not be used by a person speaking of himself, and therefore may be presumed to be the product of a later hand, or at the least to have been revised by one. Sections 42 to 44 detail stories of Hui-neng and various priests who come to question him, and can be classified as late additions to the legend of Hui-neng. Sections 45 and 46 detail the theory of the thirty-six confrontations. This theory is not found elsewhere, and its origin is completely unknown. One does not hear of it in other Ch’an works, although it is retained in all later versions of the text. The fact that it has been retained, although never discussed or enlarged upon elsewhere, points to the esteem in which Hui-neng was held. In that these sections were believed to represent the teachings of Hui-neng, they were preserved regardless of the fact that their import is obscure. In section 49, which contains the prediction concerning the appearance of Shen-hui, are included the transmission verses of the six Chinese Patriarchs. As has been seen, these verses seem to have gained a considerable importance in the eighth century as a part of the legend, and they play a significant role in the Pao-lin chuan. Their inclusion here represents one stage in their development, probably earlier than those to be found in the latter work. Section 50 contains two additional transmission verses, attributed to Hui-neng; these are not found in later versions of the Platform Sutra. Section 51 furnishes the list of the Indian and Chinese Patriarchs, and, as noted before, can be dated sometime between the completion of the Li-tai fa-pao chi and the compilation of the Pao’lin chuan. Sections 52 to 54 contain verses attributed to Hui-neng, which can be assigned a late origin, as well as a description of the Master’s death.

What conclusions can now be drawn about the Tun-huang edition of the Platform Sutra? Obviously, it is composed of two basic parts: the sermons at the Ta-fan Temple, including the autobiographical section, which if not a later addition, has undoubtedly been revised; and other material, added at a later date. The problem of the authenticity of the early section cannot be resolved. The lack of a text in any earlier form, the haziness surrounding Fa-hai, the alleged compiler, the similarity of many parts of the sermon to Shen-hui’s works, the fact that no mention of the Platform Sutra is found among the works of Shen-hui, the lack of any reliable information concerning the Ta-fan Temple where Hui-neng’s sermons are said to have been delivered, all contribute to the conviction that the Platform Sutra was purely a product of Shen-hui’s school. Yet we cannot explicitly state that there was no Fa-hai, that he or some other disciples did not record the sayings of Hui-neng, and that they have not been revised, augmented, and changed to form the first part of the present version of the Platform Sutra.

There are two references that are used to support the thesis that an original version of the Platform Sutra existed, and that it was compiled shortly after Hui-neng’s death. One is a notice in the Ching-te ch’uan-ten g lu, contained in the sayings of Nan-yang Hui-chung (d. 775),20 a disciple of the Sixth Patriarch, in which he laments the condition in which the Platform Sutra now exists. He complains that the work has been vulgarized, changed, and added to, so that the sacred import has been distorted, that this has created confusion among students who have come later, and that therefore the teaching is threatened with destruction. Ui believes that Hui-chung, who died in 775 after having been called to the imperial court in 761, must have made this comment prior to his entrance into the palace, and that this therefore indicates that the Platform Sutra was already in a state of confusion at this time.21 Since the earliest source for this comment is the Ching-te ch’uan-teng lu, compiled in 1004, some 280 years after Hui-chung’s death, and since there is no corroborating source for the statement, considerable doubts concerning the reliability of the information may be justified.

The second reference used by advocates of an early version of the Platform Sutra is an inscription by Wei Ch’u-hou (773–828) for E-hu Ta-i (d. 818),22 a disciple of Ma-tsu. The text contains a passage that characterizes four different branches of Ch’an: the Northern school, the Southern school of Shen-hui, the Oxhead school, and the teaching of Ma-tsu Tao-i. In the description of the school of Shen-hui there is a passage whose meaning has been disputed. Ui takes it to mean that in Loyang Shen-hui, receiving the teaching of Hui-neng, alone illumined the precious jewel, but, his followers being unable to distinguish the true from the false, “the orange tree changed into the thorn bush,” and the Platform Sutra became what it is now. Ultimately, possession of a transmitted copy of the text served to reveal the status of the transmitted teaching. This interpretation is taken to show that the followers of Shen-hui distorted the original work, and made it into what it is today, merely a symbol to prove the possession of the teaching.23 Hu Shih, on the other hand, understands the passage to mean that the disciples of Southern Ch’an were deluded in the truth and that contradictions confused the doctrine. Finally the Platform Sutra was composed, and the true teaching transmitted, making clear the good and the bad in the various contradictory opinions. This, Hu Shih believed, indicated that Shen-hui composed the Platform Sutra.24 The text is too obscure to determine which of these two interpretations is correct; needless to say, this inscription cannot safely be used as an argument to determine the authorship and provenance of the Platform Sutra. It can, however, be used to date the work. If we can assume that the reference here is to a text similar to the Tun-huang version, it would necessarily have to have been in existence prior to Wei Ch’u-hou’s death in 828, and quite probably prior to Ta-i’s death in 818.

We can safely say that the Tun-huang version of the Platform Sutra was made between 830 and 860, and represented a copy of an earlier version, some of whose material dates to around 780. There were at one time probably a considerable number of copies extant, distributed over a fairly wide area of China. Some manuscripts, we know, made their way to Japan, although they are no longer preserved. Of the evolution of the text during the ninth century we know nothing. Examination of the lists of Buddhist scriptural works brought back to Japan by Japanese priests indicates that by the mid-ninth century the title had been considerably simplified; the text is no longer known under the cumbersome titles that the Tun-huang manuscript or the version found in Ennin’s list of 847 bear. It is quite possible that these versions did not contain the vast number of errors that are to be found in the Tun-huang edition. We also do not know in what schools of Ch’an the text was used. Presumably it was venerated by the branch which made its home at Ts’ao-ch’i and by the followers of Shen-hui’s line, although by the mid-ninth century these schools may have been virtually extinct. To what extent it was taken up by the new schools of Ch’an that came into prominence at this time is also unknown. If it was, these schools made no effort to eliminate elements in the text which were of no concern to them—the struggle between Northern and Southern Ch’an, the emphasis on Shen-hui, the lineage of Fa-hai’s school—for these elements are retained in versions of the Platform Sutra produced at a considerably later period. Stories about Hui-neng, however, do appear in the records of the Ch’an Masters of the ninth century,25 so that we know that the Sixth Patriarch was held in high regard by the Ch’an Masters of late T’ang, although we cannot say to what extent the book ascribed to him was used.

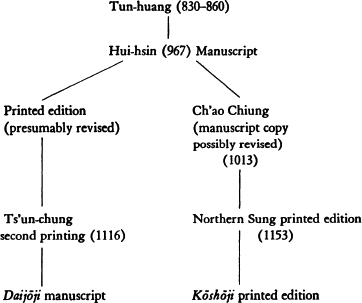

The next text of the Platform Sutra of which we have evidence is an edition of 967, compiled by a priest named Hui-hsin, of whom nothing is known. This text is no longer extant; our knowledge of it derives from the preface to the Kōshōji edition,26 a printed text, based on a “Gozan” edition, which itself was a direct copy of a Northern Sung edition of 1153. The preface to the Kōshōji edition is handwritten, copied from some other source by the Japanese priest Ryōnen (1559–1619)27 in 1599. It is apparent that the printed text in Ryōnen’s possession was incomplete, and that he supplemented the missing preface by copying it by hand from another text, presumably the “Gozan” edition. In reproducing it, however, Ryōnen made a mistake, or reproduced a prior error; he combined what originally were two prefaces to form one. The first preface is by Hui-hsin. In it he describes how poor the condition of the “old” Platform Sutra was: the text was obscure, and students, first taking it up with great expectations, soon came to despise the work. Therefore he revised it, dividing it into eleven sections and two chüan. The preface bears only a cyclical date, but this has been identified as representing the year 967,28

The second preface is by Ch’ao Tzu-chien29 and is dated 1153. In it Ch’ao describes how, on a visit to Szechuan, he found a manuscript copy of the Platform Sutra, in the handwriting of his ancestor, Wen-yüan, to which was affixed a note to the effect that his ancestor had seen the work now for the sixteenth time and that he was in his eighty-first year at the time. Hu Shih has demonstrated that this Wen-yüan was Ch’ao Chiung,30 and that the year in which he was eighty-one was 1031. Thus we know that the Kōshōji text is based on a “Gozan” copy of the Sung printed edition of 1153, which in turn derived from a manuscript copy dated 1031, which was itself copied from Hui-hsin’s version of 967. Hui-hsin’s text was in turn derived from a copy of the Platform Sutra similar to the Tun-huang text, somewhat later in date, but covering largely the same material.

Before proceeding further, we must take notice of the other Northern Sung text, the so-called Daijōji edition.31 Legend has it that the manuscript is in the hand of Dōgen, generally regarded as the founder of the Japanese Sōtō sect of Zen, but it is more likely that it was made by one of his disciples.32 It is quite close to the Kōshōji version, and is similarly divided into eleven sections and two chüan, yet considerable differences in the two texts can be noted. The Kōshōji edition is more polished and avoids several careless errors that are present in the Daijōji text, but the relationship between the two editions is not clear. The Daijōji text contains a preface by a certain Ts’un-chung, a priest of whom nothing is known, who lived at Chiang-chün-shan in Fu-t’ang.33 The preface provides little information; it does, however, state that the work represents a second printing. It is dated 1116. Suzuki reasons that because of various additions to the Kōshōji text that are not to be found in the Daijōji version, such as the famous story of the banner and the wind, the former work was influenced by the Sōkei daishi betsuden, and represents a later version of the text. His assumption is that the Kōshōji text is a revised and enlarged version of the Daijōji edition.34 However, as Ōkubo points out,35 Hui-hsin states in his preface that he himself divided the work into eleven sections and two chüan. Unless Hui-hsin’s statement is to be doubted, then the Daijōji edition represents a manuscript copy of a reprint of the Hui-hsin version itself. Thus, according to Ōkubo, the Hui-hsin and the Daijōji texts are the same. This would then indicate that Hui-hsin’s version was a printed text. Ōkubo believes that Ch’ao Chiung, being a prominent figure in the literary world, edited the work, and it is this version that is represented by the Kōshōji edition. These theories must, however, be regarded as speculations which, at this point, cannot be verified.

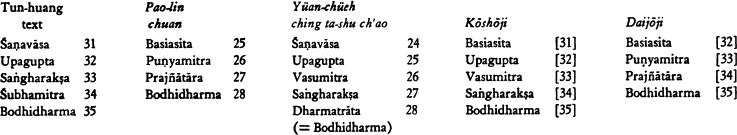

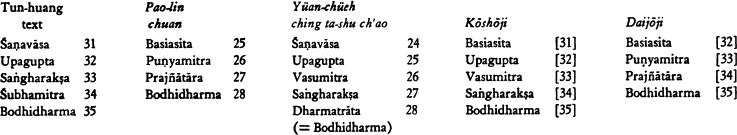

I am inclined to believe, and this again is purely speculation, that both the Daijōji and Kōshōji texts represent edited versions of Hui-hsin’s manuscript edition of 967. There seems no particular reason to doubt Hui-hsin’s statement that he divided the Platform Sutra into eleven sections and two chüan, and since both Northern Sung editions follow this division, it would seem possible to assume that they are derived from the same work. There is, apart from the differences already alluded to, one significant place where the two texts are at variance: this is in the theory of the twenty-eight Indian Patriarchs. The Kōshōji text, with certain changes, follows largely the version found in the Tun-huang manuscript. The Daijōji version, on the other hand, is based on the Pao-lin chuan. Thus, for the last few Indian Patriarchs we have the names given in Table 2.

TABLE 2. THE LAST INDIAN PATRIARCHS

From this table, I conclude that the Hui-hsin text followed the Tun-huang version of the twenty-eight Patriarch theory, in its corrected version, as found in Tsung-mi’s Yüan-chüeh ching ta-shu ch’ao,36 and continued to include the Seven Buddhas of the Past in the numbering scheme. This, in turn, was repeated in the Kōshōji text.37 The Dai-jōji edition, on the other hand, while retaining the numbering system employed in the Tun-huang manuscript, is based entirely on the Pao-lin chuan, and must therefore represent a different edited version of the Hui-hsin text. The preface to the Daijōji text, however, clearly states that it is a second printing. I would suggest that there may be a missing first printing of the Daijōji text, which was itself a revision of Hui-hsin’s manuscript, and that this text belonged to a school of Ch’an which had at the time already accepted the Pao-lin chuan version of the patriarchal tradition. In diagram form, the evolution of the text would be as follows:

Since the Tun-huang, the Daijōji, and the Kōshōji editions contain the sections relating to the transmission of the text in Fa-hai’s school, it would seem permissible to assume that both the Tun-huang version and the copy on which Hui-hsin based his edition represented versions of extremely limited distribution. With Hui-hsin’s text of 967, however, the text most probably became available to other schools of Ch’an. Support for this conclusion is found in the Ching-te ch’uan-teng lu of 1004, which mentions the Platform Sutra by name, and indicates that it was in wide use.38 Thus what had been a text of comparatively small distribution became available to all branches of the sect and to the Sung literati in general by virtue of Hui-hsin’s edition. The Daijōji version may then represent the text as adopted by one of the Ch’an schools which derived ultimately from the schools of Nan-yüeh and Ch’ing-yüan, and the Kōshōji text may well represent the text as taken up by the Sung literati, among whom a refined copy of the text was more important than such details as the accuracy of the transmission of the then accepted patriarchal tradition.

No detailed comparison of the Tun-huang text with the two Northern Sung editions will be attempted here. The latter works have been greatly refined, many errors have been corrected, and the texts somewhat enlarged.39 The texts are sufficiently similar that there can be no question that these later versions were derived from a copy similar to the Tun-huang copy.40

Between the time that Hui-hsin’s version was composed and the two Northern Sung editions appeared, we hear of still another version of the Platform Sutra. Here again we must deal with a text that is no longer extant; however we have three references to this edition.41

1. The Ch’ü-chou edition of the Chün-chai tu-shu chih contains a notice of a Liu-tsu t’an-ching in 16 sections and 3 chüan, compiled by Hui-hsin.42

2. In the Wen-hsien t’ung-k’ao, chüan 54, there is a notice listing a Liu-tsu t’an-ching in 3 chüan. No compiler is given.43

3. The Hsin-chin wen-chi, chüan 11, compiled by the famous Sung priest Ch’i-sung (1007–1072)44 contains a preface by the shih-lang Lang,45 entitled Liu-tsu fa-pao chi hsü46 Dated 1056, it relates the history of the partriarchal succession from Bodhidharma through Hui-neng, remarks on the veneration which the words of the Sixth Patriarch are accorded, and expresses regret that common people have vulgarized and proliferated his teaching. Lang goes on to note that Ch’i-sung had written a piece in praise of the Platform Sutra,47 and that two years after this was completed he had obtained a copy of an “old Ts’ao-ch’i edition,” which he edited, corrected, divided into three chüan, and later published.

Ch’i-sung’s missing edition has been the source of further controversy. Its importance lies in the fact that it was evidently one of the sources for the greatly expanded Yuan editions of the Platform Sutra, which are clearly based on an edition that differs from Hui-hsin’s version. Hu Shih holds that the “old Ts’ao-ch’i edition” mentioned in Lang’s preface referred to the Sōkei daishi betsuden, and that Ch’i-sung combined it with the Hui-hsin edition to form his new three-chüan work, retaining Hui-hsin’s name as compiler.48 Ui completely rejects Hu Shih’s conclusions, saying that, because of differences in style between the Sōkei daishi betsuden and the then existing texts of the Platform Sutra, Ch’i-sung, who had written in praise of the Platform Sutra, could not conceivably have considered the Sōkei daishi betsuden as an “old Ts’ao-ch’i edition.”49

Here again there is no ready answer. Ch’i-sung’s edition no longer exists, so that we cannot determine to what degree he enlarged or revised the text. There are, however, two Yuan editions, published independently, and apparently without reference to each other, one year apart, in 1290 and 1291. These two editions are very similar, and have obviously been based on the same work, which must be presumed to have been Ch’i-sung’s missing text, or possibly a later revision of it. The two Yuan editions are greatly expanded, and include much new material not previously associated with the Platform Sutra. Thus Ch’i-sung’s version, which is listed as being in three chüan, must also be presumed to have been an enlarged text.

Hu Shih has suggested that Ch’i-sung enlarged the Platform Sutra on the basis of the Sōkei daishi betsuden. There is no evidence, however, that the latter work was ever used to any significant extent in China. It has not been preserved in that country, nor do we find textual references to it. It would seem more likely that the “old Ts’ao-ch’i edition” on which Ch’i-sung depended was the Pao-lin chuan.50 Although the volumes relating to Hui-neng are missing, it may be presumed that it contained a considerable body of material concerning him. At any rate, Ch’i-sung’s edition must be added to the already long list of insoluble problems relating to the Platform Sutra and its authorship. It is perhaps significant, however, that the edition of 1036 and that of 1056 were both edited by men who had strong ties to contemporary literary circles. We do not know precisely what Ch’ao Chiung’s religious commitments were, but he is said to have read the Platform Sutra sixteen times before making a copy of it, so that it obviously exerted a considerable influence upon him. Ch’i-sung, although a Ch’an priest, was widely associated with persons outside his clerical environment, and it may be assumed that his edition of the Platform Sutra was not without literary polish. Thus it is evident that this work, in its revised versions, was gaining an audience not solely confined to the priesthood. As noted before, it was also in Ch’i-sung’s time, or shortly after his death, that the Platform Sutra and the Pao-lin chuan were both excluded from the Tripitaka as spurious works, which might, to a certain extent, account for the failure of Ch’i-sung’s version to survive.

The history of the Platform Sutra during the Yuan, Ming, and Ch’ing dynasties is of enormous complexity, and a detailed study of the various editions is quite beyond the scope of this introduction.51 As has been mentioned, two editions appeared, a year apart, in 1290 and 1291. They represent different printings in widely separated areas of China, and do not appear to be based on each other, although they are sufficiently similar that they must have been based on the same source. The printing of 1290 was edited by Te-i.52 In his preface he remarks: “The Platform Sutra has been greatly abridged by later writers and the complete import [of the teachings] of the Sixth Patriarch is difficult to discern. When I was young I saw a copy of an old edition, and since then I have spent thirty years searching for it.” Te-i goes on to explain how a certain T’ung shang-jen obtained a copy for him, and that he had it published at the Hsiu-hsiu an in Wu-chung.53 It would seem then that Te-i had access to a version of the Hui-hsin edition, but that in his youth he had seen a copy of a greatly enlarged text, which we may assume to have been the Ch’i-sung edition or a version of it. Eventually finding another copy, he had it printed. So far from the original Tun-huang version had the text been expanded that Te-i saw fit to condemn what was presumably a text of the Hui-hsin version for having been abbreviated.

In 1291 a priest by the name of Tsung-pao54 published another edition, very similar to that of Te-i, at Nan-hai in south China. It is this version that was incorporated into the Ming Tripitaka and is the popular edition in general use today.55 At the time that it was added to the Tripitaka Te-i’s preface was attached to the Tsung-pao text, which has created a certain confusion in distinguishing the two works. In his postface Tsung-pao explains that he obtained three editions which he edited to make one volume, adding material on the relationships of various disciples with the Sixth Patriarch. This latter material is, however, also in the Te-i text. Since the Tsung-pao text was published later and the compiler claims to have added the material himself, either his statement is in error, or we must look for some other explanation. Ui suggests that Tsung-pao spoke in terms of one or two of the three editions that he used, and that these contained only a few such stories when compared with the third text of which he made use.56 In any event, at the present state of our knowledge, it seems safe to say that the Te-i and Tsung-pao texts were produced separately, but must have been based on the same source, Ch’i-sung’s missing edition of the Platform Sutra.

Both Yüan editions divide the text into ten sections; there are certain differences within the sections, and the titles given to each section are at variance.57 Te-i gives Fa-hai as the compiler, placing his name at the head of the text of Fa-hai’s preface. The Kōshōji and Daijōji editions mention Fa-hai as compiler only in the body of the text. Tsung-pao, on the other hand, uses his own name as the compiler of the work. The chief difference in the two Yuan texts lies in the amount of supplementary material that is attached. Te-i includes only his preface and the one attributed to Fa-hai. The Tsung-pao edition contains Te-i’s preface, Ch’i-sung’s words in praise of the Platform Sutra, Fa-hai’s preface, the texts of various inscriptions, and Tsung-pao’s postface.

No comparison of the Yuan editions with the Tun-huang text will be attempted. The former contain much of the same material found in the autobiographical sections and the sermon, retain many of the stories of encounters with other priests, as well as the discussion of the thirty-six confrontations and the list of the Indian Patriarchs, and some of the verses, but the text is much refined and greatly expanded throughout. The sections relating to Fa-hai and the transmission of the text have been dropped. As a result of all these alterations, the Tsung-pao text is almost twice the size of its Tun-huang counterpart.

Judging only from the great number of printings and editions, the Platform Sutra attained a tremendous circulation during the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties.58 These editions vary slightly in arrangement and often contain additional prefatory material. What role this work played in the Ch’an teaching of the time cannot be considered without relating it to the vast changes which took place in Ch’an after the Yuan dynasty. The large number of printings would indicate that the work was widely used by lay believers as well as Ch’an priests, but an investigation of the whole range of Chinese Buddhism in the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties would be required in order to reveal its significance in the Buddhism of this time. This cannot be undertaken here.

In Japan Zen arrived as a sect during the Southern Sung and Yüan dynasties, particularly during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries when large numbers of priests visited the continent and Chinese Masters, often refugees, came to Japan to teach or to make their homes. Various degrees and kinds of teaching were represented, but largely what was introduced was the highly organized kōan Zen that developed during the Sung dynasty. These priests brought with them numerous works, such as the renowned kōan collections Pi-yen lu and Wu-men kuan, and the “discourses” of eminent priests. Although the Yuan version of the Platform Sutra had yet to appear when the intercourse between Chinese and Japanese priests was at its height, there was still ample contact in the first half of the fourteenth century to have made it possible for the work to have been introduced to Japan at that time.59 But this does not seem to have been the case, for it was not until 1634 that there was a Japanese edition of the Yuan version of the Platform Sutra.60 During the Tokugawa period several printings and a number of commentaries appeared, but neither the Sung nor the Yüan versions appear to have played an important part in the Zen schools of Japan. Hui-neng is, of course, revered as the Sixth Patriarch; stories of him are known and used, and he appears prominently in kōan collections. The Kattō-shū,61 a collection much used in Japanese Zen monasteries today, contains a story about Hui-neng’s encounter with the fierce Hui-ming atop Mount Ta-yü, when the latter came in pursuit of the Dharma.62As the account goes, Hui-ming gained enlightenment when Hui-neng asked: “Not thinking of good, not thinking of evil, just at this moment, what is your original face before your mother and father were born?” This is an important kōan, one of the first given the beginning student. But it is also a part of the legend, for the story is not mentioned in the Tun-huang edition, and appears only later in the Sung version of the Platform Sutra.63 Thus, the Platform Sutra and the Patriarch it champions continue to exert their influence today.

1 S5475. It was first reproduced in facsimile form in Yabuki Keiki, Meisha yoin, plates 102–103. The text also appears in printed form in Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, T48, pp. 377a–45b; however, the large number of errors contained make it unsuitable for purposes of citation. An edited text was published by D. T. Suzuki and Kuda Rentarō, Tonkō. shutsudo Rokuso Dankyō. This text was divided by the compilers into 57 sections, and for convenience this division has been maintained in the translation and text given here. Another edited version was published by Ui Hakuju, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 117–72. A translation with text, was made by W. T. Chan, The Platform Scripture.

2 Professor Akira Fujieda of the Research Institute for Humanistic Studies, Kyoto University, the leading expert on Tun-huang calligraphy, has been kind enough to examine the photographs of the original manuscript, and in his judgment it dates to this period. While a study of the document itself would produce more conclusive evidence, the style of writing indicates the possibility that in certain portions of the text a pen was used to simulate brush strokes. This is a peculiarity found in the Tun-huang writing style of this period.

3 A printed version, probably a reprinting of the “Gozan” copy (see Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyūy II, 113) of the Sung text was discovered at Kōshōji in Kyoto. This was reproduced photolithographically by D. T. Suzuki, Rokuso dankyō. A printed edition of the same work was published by D. T. Suzuki and Kuda Rentarō, Kōshōji-bon Rokuso dankyō (hereinafter referred to as Kōshōji). Another version of this text was recently discovered at the Kokubunji in Sendai. Known as the Murayama edition, after the name of the head priest of the temple, it quite possibly is the “Gozan” copy of the Sung text, of which the Kōshōji is a later printing. It is of particular importance because it contains one leaf which is missing from the Kōshōji edition. A manuscript copy, also based on a Sung edition, was found at the Daijōji in Kaga. This was first published as Kaga Daijōji shozō Shōshū Sōkeizan Rokusoshi dankyō, Komazawa Daigaku Bukkyō gakkai gakuhō, no. 8 (April, 1938), pp. 1–56 (hereinafter referred to as Daijōji). An edited and indexed edition was later published: D. T. Suzuki, Shōshū Sōkeizan Rokusoshi dankyō. It is discussed by D. T. Suzuki, “Kaga Daijōji shozō no ‘Rokuso dankyō’ to ‘Ichiya Hekigan’ ni tsuite,” Shina Bukkyō shigaku, I (no. 3, October, 1937), 1–23 and Ōkubo Dōshū, “Daijõji-bon o chūshin to seru Rokuso dankyō no kenkyū,” Komazawa Daigaku Bukkyō gakkai gakuhō, no. 8 (April, 1938), pp. 5784.

4 The Kōshōji (p. 71) and Daijōji (p. 56) give the succession of priests as: Fa-hai—Chih-tao—Pi-an—Wu-chen—Yüan-hui. A well-known priest by the name of Wu-chen flourished in the Tun-huang area during the latter half of the ninth century. Whether there is any connection with the Wu-chen mentioned here is unknown. See Chikusa Masaaki, “Tonkō no sōkan seido,” Tōhō gakuhō, no. 31 (March, 1961), pp. 127–32.

5 Under Nan-yüeh Huai-jang, we have, in the fourth generation from Hui-neng, Po-chang Huai-hai (d. 814) and Nan-ch’üan P’u-yüan (d. 834); under Ch’ing-yüan Hsing-ssu we have Yao-shan Wei-yen (d. 834); under Shen-hui, we have Feng-kuo Shen-chao (d. 838).

6 See below, p. 98.

7 Nitto shin gushōgyō mokuroku, T55, p. 1083b. It appears here under the title: Ts’ao-ch’i-shan ti-liu-tsu Hui-neng ta-shih shuo chien-hsing tun-chiao chih-liao cheng-jo chūeh-ting wu-i fa-pao-chi t’an-ching. Hu Shih, “An Appeal for a Systematic Search in Japan for Long-hidden T’ang Dynasty Source Materials of the Early History of Zen Buddhism,” Bukkyō to bunka, p. 16, translates: “The Dana sutra of the Treasure of the Law, preached by Hui-neng, the Sixth Patriarch, the Great Master of Ts’ao-hsi Hill, teaching the religion of sudden enlightenment through seeing one’s own nature, that Buddhahood can be achieved by direct apprehension without the slightest doubt.”

8 Fukushū Onshū Daishū gutoku kyōritsu ronshoki gesho tō mokuroku, T55, p. 1095a. The title here is simplified to: Ts’ao-ch’i-shan ti-liu-tsu Neng ta-shih t’an-ching.

9 Nihon biku Enchin nittō guhō mokuroku, T55, p. 1100c. The title here is: Ts’ao-ch’i Neng ta-shih t’an-ching.

10 Chishō daishi shōrai mokuroku, T55, p. 1106b. The title is identical with that of the list of 857.

11 See Hsiang Ta, T’ang-tai Ch’ang-an yü Hsi-yü wen-ming, p. 368. The title here is Nan-tsung tun-chiao tsui-shang ta-ch’eng t’an-ching, reminiscent of the first part of the title of the Tun-huang text.

12 Ui, operating on the assumption that an original version, recorded about 714 by Fa-hai, shortly after Hui-neng’s death, existed, has designated those portions of the text which he considers to be authentic. See Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 76-100. Hu Shih, believing the work to be a product of Shen-hui’s school, finds that the autobiographical part (sees. 2-11) and the sermon (sees. 12-31 and 34-37) formed the core of the original work. See Hu Shih, “An Appeal . . .,” p. 20.

13 The autobiographical sections might well be included under this category.

14 The Ch’ü-chiang hsien chih, ch. 16, p. 10b, states: “The Pao-en kuang-hsiao Temple lies west of the river and was founded by the monk Tsung-hsi in K’ai-yüan 2 (714). It is also called K’ai-yüan Temple, and another name is the Ta-fan Temple. This is the place where the envoy Wei Chou [sic] asked the Sixth Patriarch to preach the Platform Sutra.” Other than this, no mention of the temple can be found. The present identification can scarcely be regarded as reliable in view of the lack of confirming sources, the date 714, which is after Hui-neng’s death, and the error in the identification of Wei Chou (see Translation, sec. 1). Wei Chou (HTS, 197, pp. 15b-16b) died between 860 and 873. Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 214, surmises that the temple was located within the walls of Shao-chou.

15 Precise references to the points of similarity are indicated in the notes to the translation.

16 D. T. Suzuki, Zen Doctrine of No-mind, p. 22.

17 From the first not a thing is” appears as the third line of Hui-neng’s verse, given in answer to Shen-hsiu, in the Kōshōji, p. 14, and Daijōji, p. 10. In the Tun-huang text (see sec. 8) it is found as “Buddha nature is always clean and pure.” The line, in its altered version, is contained also in Huang-po’s Ch’uan-hsin fa-yao, T48, p. 385b. Since Huang-po died around 850, this is probably the first instance in which the phrase is to be found. Caution, however, must be used when citing the “discourses” of the famous Ch’an priests of the T’ang dynasty, for their works, as recorded by their disciples, were not published until the Sung period or later, and if they received, even to a limited extent, the editing, revision, and emendation to which the Platform Sutra was subjected, certain reservations as to how well they reflect the exact sayings of the Patriarch in question must be entertained.

18 The Kōshōji (p. 15) and Daijōji (p. 11) say that Hui-neng’s enlightenment came when he heard the passage from the Diamond Sutra: “Must produce a mind which stays in no place” (T8, p. 749c). See Itō Kokan, “Rokuso Enō Daishi no chūshin shisō,” Nihon Bukhyō gakkai nempō, no. 7 (1934), p. 214.

19 The view has been advanced that Fa-hai transcribed an original text and that Shen-hui made it into a “transmitted” one, to show the errors of Northern Ch’an and to establish it in the tradition of his school, and that later sections were added by Shen-hui’s followers. See Nakagawa Taka, “Dankyō no shisōshiteki kenkyū,” IBK, no. 5 (September, 1954), p. 284.

20 The notice is contained in chüan 28, T51, p. 438a. Hui-chung’s biography appears in chüan 5, pp. 244a-45a. Chüan 28-30 of the Ching-te ch’uan-teng lu contain miscellaneous passages and writings of various priests, which are not included under their separate biographies. His biography is also in Sung kao-seng chuan, T50, pp. 762b-63b and Tsu-t’ang chi, I, 113-30. They contain conflicting information. For a discussion, see Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 281-94.

21 Ibid., II, 110-11.

22 See Hsing-fu-ssu nei-tao-ch’ang kung-feng ta-te Ta-i ch’an-shih pei-ming, CTW, ch. 715 (XV, 9311-13). The problems entailed in this inscription are discussed by Takao Giken, “Futatabi Zen no Namboku ryōshū ni tsuite,” Ryūkoku gakuhō, no. 306 (July, 1933), pp. 112-14 and Gernet, “Biographie du Maître Chen-houei du Ho-tsö,” Journal Asiatique, CCXLIX (1951), 37-38, n. 2c.

23 Ui, Zenshū shi Kenkyū, II, 111-12.

24 Hu Shih, Shen-hui ho-shang t-chi, pp. 75-76. He later revised his opinion to indicate that it was composed by Shen-hui’s disciples. See Hu Shih, “Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism in China, Its History and Method,” Philosophy East and West, III (no. 1, April, 1953), 11, n. 9.

25 See p. 94, n. 27.

26 See p. 90, n. 3.

27 He was the founder of the Kōshōji in Kyoto. See Matsumoto Bunzaburō, Bukkyō shi zakkō, p. 101.

28 This and the following information are drawn largely from Hu Shih, “T’an-ching k’ao chih erh,” Hu Shih wen-ts’un, IV, 301-18. The preface is also discussed in D. T. Suzuki, “Kōshōji-bon Rokuso dankyō kaisetsu,” contained in the separate volume of explanatory material accompanying Suzuki’s texts of the Tun-huang and Kōshōji versions of the Platform Sutra and the Shen-hui yü-lu, pp. 44-58.

29 Biography unknown.

30 Biography in Sung shu 305, pp. 7a-9b.

31 See p. 90, n. 3.

32 Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 61. It is of interest to note that Dōgen, in his Shōbō genzō, remarks: “The Platform Sutra is a spurious work and does not represent the transmission of the Dharma-treasure. These are not the words of the Sixth Patriarch” (T82, p. 298b). This passage has caused considerable debate, and some writers question the correctness of its attribution to Dōgen. For a discussion, see Itō Kokan, “Rokuso Enō daishi no chūshin shisō,” Nihon Bukkyōgaku kyōkai nempō, no. 7 (February, 1935), pp. 226-29.

33 Southeast of Fu-ch’ing hsien, Fukien.

34 Suzuki, “Kaga Daijōji shozō no Rokuso dankyō . . .,” p. 6.

35 Ōkubo, “Daijōji-bon . . .,” p. 69.

36 zzl, 14, 3, 276b.

37 While the Kōshōji edition follows Tsung-mi, it changes Śaṇavāsa to Basiasita, as found in the Pao-lin chuan. The reason for this change cannot be determined.

38 T51, p. 235c.

39 See Hu Shih, “T’an-ching k’ao chih-erh,” pp. 312-13. A count of the texts shows that the Tun-huang version has 12,000 characters, the Kōshōji edition 14,000, and the Yüan edition 21,000.

40 In the translation that follows, the Kōshōji version has, in many instances, been relied on to solve textual problems. References are cited in the notes to the translation.

41 The following information is based largely on Hu Shih, “T’an-ching k’ao chih-erh,” and Matsumoto Bunzaburō, Bukkyō shi zakkō, p. 91.

42 Ch’ao Kung-wu, comp., Wang Hsien-ch’ien, ed., Chün-chai tu-shu chih, ch. 16, pp. 27b-28a. The Yüan-chou edition of this work lists the Liu-tsu t’an-ching in 2 chüan and 16 sections (Ssu-pu tsung-k’an, ser. 3, case 19, ch. 3B, pp. 26b-37a).

43 Ma Tuan-lin, Wen-hsien t’ung-k’ao, p. 1819c.

44 Prominent also as a literary figure, Ch’i-sung was active in defending Ch’an against attacks by the T’ien-t’ai sect, which challenged the Ch’an theory of the twenty-eight Patriarchs. He wrote several histories of Ch’an, was well versed in the Classics, and was active in efforts to effect a union between Buddhism and Confucianism. His biography appears in Hsü ch’uan-teng lu, T51, p. 494a-b.

45 See Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 48, for a brief notice of his career.

46 T52, p. 703b-c.

47 The T’an-ching tsan, T52, pp. 662c-64b. It is also contained in the Yuan version of the Platform Sutra as found in the Taishō Tripitaka (T48, pp. 346a-47c).

48 See Hu Shih, “T’an-ching k’ao chih-erh,” pp. 306-11. Hu Shih’s arguments here are not too convincing; however, his article was written before the Pao-lin chuan was rediscovered, and he did not have access to the Tsu-t’ang chi. On the basis of Ch’i-sung’s Ch’an history, Ch’uan-fa cheng-tsung-chi, T51, pp. 715-68, Hu credits Ch’i-sung with having established the theory of the twenty-eight Patriarchs in its final form, and argues that Ch’i-sung knew the Sōkei daishi betsuden, because he changed the prediction made by Hui-neng that twenty years after his death someone would come forward and “raise up his essential teachings” (see translation, sec. 49), to one of seventy years, as found in the Sōkei daishi betsuden. This change is found, however, in the Tsu-t’ang chi (I, 99) and the Ching-te ch’uan-teng lu (T51, p. 236c), considerably before Ch’i-sung’s time. The twenty-eight Patriarch theory, of course, derives from the Pao-lin chuan.

49 Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 49.

50 The full title of the Pao-lin chuan contains the name Ts’ao-ch’i.

51 For bibliographical studies, see Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 2-47; Matsumoto Bunzaburō, BukKyō shi zakkō, pp. 87-168; Nakagawa Taka, “Rokuso dankyō no ihon ni tsuite,” IBK, no. 3 (September, 1953), pp. 155-56. For the history of Korean editions, see Kuroda Akira, Chōsen kyūsho kō, pp. 93-111 and Kuroda Akira, “Rokuso dankyō kō iho,” Sekisui sensei kakōju ki’nen ronsan, pp. 153-79. A detailed listing of all printing is found in Shinsan zenseki mokuroku, pp. 447-49.

52 The Te-i edition is comparatively rare in China; see Li Chia-yen “Liu-tsu t’an-ching Te-i pen chih fa-hsien,” Ching-hua hsüeh-pao, X (no. 2, April, 1935), pp. 483-90. For the text of the Te-i edition, see Gen Enyū Kōrai kokubon Rokuso daishi hōbō dankyō, Zengaku kenkyū, no. 23 (July, 1935), pp. 1-63. This is the Korean edition of 1316. The Te-i edition made its way to Korea shortly after publication, and most Korean versions stem from it. For Te-i’s biography, see Tseng-chi hsü ch’uan-teng-lu, zz2B, 15, 5, 416b-17a. His dates are unknown.

53 Wu-hsien, Chiangsu.

54 Biography unknown.

55 T48, pp. 345-65. Translated under the title “The Dharma Treasure of the Altar Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch,” by Lu Kuan-yü (Charles Luk), Ch’an and Zen teachings (series 3), pp. 15-102.

56 Ui, Zenshū shi kenkyū, II, 49.

57 For a comparison of the two Yüan editions, see Ōya Tokujō, “Gen Enyū Kōrai kokubon Rokuso daishi hōbō dankyō ni tsuite,” Zengaku kenkyū, no. 23 (July, 1935), pp. 1-29.

58 The Shinsan zenseki mokuroku, p. 448, lists some 26 different editions produced in Korea and China during Ming and Ch’ing times. How many printings were made from each set of blocks is unknown.

59 A Korean version of the Te-i edition had already appeared in 1316.

60 A text of the Tsung-pao edition was printed in Kyoto in Kan’ei 11. See Shinsan zenseki mokuroku, p. 447.

61 First published 1689. Contained in Fujita Genro, Zudokko, pp. 109-97.

62 Ibid” p. 117. The same kōan is found in Wu-men kuan, T48, p. 295c.

63 It appears first as a note at the end of the section dealing with Hui-neng’s departure from the Fifth Patriarch in the Kōshōji edition, p. 17. The story is also found, in a slightly variant form, in the Ch’uan-hsin fa-yao, T48, p. 384a.