Chapter 32

Providing for the Possibility of Incapacitation

It has been reported that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis refused life-prolonging medical intervention before her death from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and that former president Richard Nixon insisted on receiving comfort-easing care only—not any heroic measures. They both made sure their wishes were satisfied through use of advance directives.

Section 1. An Overview of Advance Directives

Advance directives ensure that your wishes with respect to physical and financial matters will be carried out if you lose the capacity to make such decisions for yourself.

Physical matters. If you become incapacitated and don’t have advance directives:

• Medical authorities can, and may even be required by law to, extend your life for years, no matter how meager the existence and at your expense.

• In an emergency, your consent to a procedure will be assumed. At other times, someone else, generally your legal next of kin, will have to make stressful decisions without your guidance. A court may appoint a person to make the decisions. The appointee may be a relative or a stranger.

• People you may want to make these decisions will not be considered, particularly if they are not your legal next of kin.

• You can expect extraordinary medical charges. According to one study (among many that reach the same conclusion), hospital charges for last hospitalizations for Medicare patients averaged more than $95,000 per patient. Yet, the average cost for patients with a type of advance directive known as a living will was only $30,000.

Financial matters. If you become incapacitated and someone doesn’t tend to your financial health, it can become disastrous. Aside from the possibility of losing your residence because no one has the authority to pay the rent or mortgage, you could lose all your medical coverage and life insurance because no one is paying the premiums. Also, no one could act quickly in a financial emergency without costly and time-consuming court guardianship proceedings for authorization.

If incapacity occurs and appropriate steps have not been taken, an interested party would have to go to court with whatever documentation the court requires. Time-consuming notice would have to be given to all interested parties. If there is money involved, you can expect that relatives and creditors will come pouring out of the woodwork. Obviously, having a court sort out your finances can involve much time and expense.

Complementary. The different advance directives may seem duplicative but they actually complement each other.

State law and forms. Check the laws of your state to determine the legal requirements for advance directives; e.g., some states that recognize living wills do not allow any restrictions on food and water. Be sure the wording of the document and your execution of it conform precisely to the state law.

The specific forms and the execution requirements for each state can easily be obtained. For instance, the Cancer Information Service at 800-422-6237 has information on how to obtain the forms for your state. For a fee of $3.50 per set ($3.79 for New York State residents and $3.70 for residents of Washington, D.C.), appropriate state documents can also be obtained from Choice in Dying, a nonprofit organization located at 200 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014 (800-989-9455 or 212-366-5540), or they can be obtained free from Choice in Dying via the Internet at www.choices.org. Any hospital or medical care facility in your area should also be able to supply you with this information, or consult the sources listed in the resources section.

If you live in a state that does not legally recognize advance directives, or if an advance directive is improperly executed. It is still important to state your wishes in writing. Even if the directive does not have the force of law behind it, the right physician or court will be likely to abide by your wishes.

The advice of an attorney may be helpful to ensure that your documents accurately reflect your wishes and are legally effective.

Travel between states. If you split your time between states, be sure the documents meet the requirements of each state. Alternatively, create a separate document for each state in the form preferred by that state. Even though a majority of states have reciprocity agreements that honor out-of-state documents, the advantage to using multiple directives is that familiarity with the state-approved form may prevent delays in validation. A costly delay may occur while lawyers, nurses, doctors, or technicians study an unfamiliar form.

Choosing your agent. In general, any designated agent should be

• at least eighteen years old.

• someone you are confident will fight for your wishes, if necessary.

• someone who is agreeable to acting as your advocate.

• ideally, someone who knows you well enough to have a clear idea of your preferences, including any religious considerations that need to be taken into account, so he or she can make an informed decision.

• available by telephone, but he or she does not have to be related to you, living with you, or even in the same area.

Even if it is legal in your state, do not consider naming your treating doctor or an employee or operator of the treating health facility as your agent. There is too great a conflict of interest.

Tip.

• Name the same agent in each of your medical advance directives, so there is no conflict. This advice does not extend to agents for business affairs or guardians of your children.

• Name more than one agent in case the first agent is unavailable when needed or refuses to serve. Be clear in the document about your order of preference and that each agent named may act separately (the word in legal terminology is severally).

• In any documents dealing with health matters, insert all of your agent’s telephone numbers including work, home, summer, and as many addresses as you have so they can be contacted as quickly as possible.

A discussion to have. Despite the emotional difficulties, discuss your wishes with your agents ahead of time. How can someone respect your wishes if you don’t make them known? It’s not necessary to drive yourself crazy thinking about every possibility, but be clear about your core beliefs, and about as many matters as are important to you.

Tip. Write a letter containing your wishes as a memory aid for your agent.

Oral directives. Since some states permit oral advance directives, it may seem that written documents are unnecessary. However, proving oral discussions is difficult (particularly if testimony is contested) and costs time and money at a time when you can’t afford to waste either.

Periodic update. Reaffirm directives by re-initialing and redating them yearly and when your circumstances change (such as when a woman becomes pregnant). Dr. Julie was reluctant to follow the wishes expressed in Graham’s living will because it was seven years old. Luckily, Graham’s son had a copy of a new living will that Graham had executed a year before but had neglected to give his doctor.

To revoke any advance directive. Any directive can be revoked at any time by destroying it and/or executing a document revoking it and notifying any persons who have copies, including your physician.

Changing agents. You can change agents at any time by notifying them and anyone else who may have a copy of the document (custodians), preferably in writing. Give custodians a new, properly executed document naming the new agent(s).

Access to the documents. Be sure to inform your spouse, significant other, and/or close friends of the existence and whereabouts of all advance directives. Do not keep them locked away, especially not in your safe-deposit box.

Tip. Advance directives concerning your health can be photocopied to a reduced size so you can carry them when traveling.

Enforcement. For assistance in ensuring that your wishes, or those of a loved one, are honored by the health care system, contact a local attorney; Choice in Dying; or Gentle Closure, 60 Santa Susana Lane, Sedona, AZ 86336 (520-282-0170).

Section 2. Health Care Power of Attorney ↑↑↑

In general, a power of attorney is a document in which you, the maker (also known as the principal), give another person (the agent or attorney-in-fact) authority to act on your behalf, as if the agent were you. The document specifies the matters to be covered, which can be specific, such as selling your house, or broad, to do just about anything you can. You determine the time during which the power of attorney is in effect. It can be effective immediately or start at a specified time or upon the occurrence of a named event.

The health care power of attorney, also known as the medical power of attorney, health care proxy, and durable health care power of attorney, is a special kind of power of attorney triggered only in the event of your incapacity or incompetence. As implied in its name, this document requires hospitals, nursing homes, doctors, and other health care providers to obey the agent’s decisions as if they were yours. In most states no adult, not even spouses, can make medical decisions for another person without this proxy. While as a practical matter your physician may listen to your spouse, why take the chance?

The document must include the word durable. Powers terminate in the event the principal becomes incompetent unless they include the word durable.

The health care power can be tailored to give your agent as little or as much authority as you choose, but generally it authorizes your agent to make all decisions regarding your health care, including

• the use or withholding of life support and other medical care.

• whether to place you in or check you out of a health facility such as a hospital.

• decisions not specifically covered by a living will.

The power of attorney can also give the agent the right

• to deal with Medicare, public benefits, and private insurance companies.

• to review your medical records.

The health care power of attorney does not

• give any authority with respect to financial matters, administering involuntary psychiatric care, or sterilization.

• generally cover medical treatment that would provide comfort or relieve pain, which means that a health care proxy cannot refuse pain relief on your behalf.

Tip. An unmarried partner is not considered a relative under the law and could be barred from visiting you. The health care power of attorney gives that person visitation rights. If you have chosen someone else as your proxy, make sure that you also create a document that provides your unmarried partner access to you.

Duration. The durable health care power of attorney generally only takes effect when two physicians, including the physician of record, certify that you are not capable of understanding or communicating decisions about your health. It will apply as long as this condition continues.

Copies. At least four original copies of a durable health care proxy should be executed: one each for the agent, your physician, your pharmacist (to permit an exchange of information without worry about invasion of your privacy), and one to take to the hospital with you should the need arise. (Consider keeping this last copy in your emergency-room bag; see chapter 29, section 3.2.) Make sure your agent knows to have the document placed in your records at the hospital in the event that you cannot present the proxy document upon admission.

Section 3. Living Wills ↑↑↑

Permitted in one form or another in all states, a living will is an advance directive that describes your “end-of-life” wishes concerning life-sustaining medical treatment and procedures in the event you become incompetent or unconscious. The living will describes the physical condition(s) the maker determines to trigger the document’s provisions, as well as the types of treatments and/or procedures to be avoided. It only becomes effective as the final statement of intent when the person who executed it is unable to make or express his or her own decisions concerning medical care. Any instruction to withdraw life support may have no effect during a female patient’s pregnancy.

A living will can be drafted in general terms such as to “withhold or withdraw any and all procedures that delay death,” or it can be drafted to be specific about authorized and unauthorized procedures. As a general matter, nutrition or water are not withheld if death would result solely from dehydration or starvation rather than an existing illness.

Tip. Check with your doctor to ensure she will abide by your directive. If your doctor won’t agree, find out why. If you can’t come to an agreement with your doctor and yet don’t want to change to another physician, perhaps she would agree to be superseded by a predesignated physician in the event of your incapacity. In some states, any doctor who is furnished a copy of the declaration is required to make it a part of the patient’s medical record and, if the doctor is unwilling to comply with the directive, must transfer the patient to a new doctor.

Your values and beliefs. Decisions about end-of-life medical treatments are deeply personal and should be based on your values and beliefs. Because it is impossible to foresee every type of circumstance, think about the quality of life that is important to you. You should consider

• your overall attitude toward life, including the activities you enjoy and situations you fear.

• your attitude about independence and control, and how you feel about losing them.

• your religious beliefs and moral convictions, and how they affect your attitude toward serious illness.

• your attitude toward health, illness, dying, and death.

• your feelings toward doctors and other caregivers.

• the impact of your decisions on family and friends.

• talking about end-of-life decisions with your family, friends, doctor, and/or a clergyperson.

Homework. Talk with your doctor to find out what may happen to people with your condition, and what treatments might be used, including life support treatments. Life support temporarily replaces or supports a failing bodily function until the body can resume normal functioning. At times, the body does not regain the ability to function without life support. Thinking about these matters will not make them happen.

Be as specific as possible. Try to identify procedures as specifically as possible so that little, if any, decision needs to be made by the people trying to carry out your wishes. For instance, instead of using a general phrase like heroic measures, which could mean any of a number of medical procedures, list your wishes about:

• Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A group of procedures performed on a person whose heart stops beating (cardiac arrest) or who stops breathing (respiratory arrest) in an attempt to restart the heart and breathing. It can include mouth-to-mouth breathing, chest compressions to mimic the heart’s function and cause the blood to circulate, or drugs, electric shocks, and artificial breathing aimed at stimulating the heart and reviving a dying person.

• Major surgery: Your wishes could be stated in terms of “major surgery” or specific surgery could be indicated.

• Respirator or other mechanical breathing: Breathing by machine through a tube in the throat to replace the function of the lungs.

• Dialysis: Cleaning the blood by machine.

• Blood transfusions.

• Artificial nutrition and/or hydration: Nutrition and/or liquid is given through a tube in a vein or in the stomach to supplement or replace ordinary eating and drinking. If you want your agent to have the right to withhold nutrition or hydration, Choice in Dying suggests it may be best to include a general statement such as “My agent knows my wishes concerning artificial nutrition and hydration.” Adding more to the general statement may unintentionally restrict your agent’s authority to act in your best interest.

• Pain medications. These may indirectly shorten life.

You could also state a general procedural preference tied to a projected outcome. For example, in the event of lung failure, you could decide that you want to be placed on a respirator if it is likely that you will survive it, but not if the likelihood for survival and return to a quality of life that is important to you is slim. You can also state your preference in terms of medications and procedures that treat the symptoms rather than the disease (such as painkillers, blood transfusions, tube feeding, or a respirator).

Relationship to health care power of attorney. It is good to have both documents. The agent named in your durable medical power of attorney becomes involved if you become unable, even temporarily, to make a health care decision. The person named in your living will only becomes involved if you are near death and a decision needs to be made about withholding or discontinuing further medical treatment or sustenance. While it is safest to designate the same person as agent in both documents, if you don’t, be sure to include a provision in your living will to the effect that “if there is a conflict between the health care proxy and this living will, then the (name the person in the selected document) shall prevail.”

Section 4. Do Not Resuscitate Order ↑↑↑

A DNR (do not resuscitate order) prohibits your medical team from taking measures to revive you in the event your heart or lungs stop functioning if you are near death. Your wishes concerning resuscitation may be contained in your living will. However, if you only want to cover this one situation, you can execute a separate DNR order.

A DNR order only applies when the heart stops beating or the lungs stop breathing. A DNR order only applies to CPR. It does not mean that other treatments are not offered or given. That is where the living will comes in.

Only a few states have laws governing DNR orders. Generally, DNR orders are regulated by a health care facility’s policies.

Note: Some states require DNR documents to be executed prior to each hospital admission in order to remain effective. If you want to have a DNR order, for safety tell the hospital admitting personnel when you are admitted to a hospital or nursing home that you want to execute a DNR (and be sure it goes into your record).

Section 5. Guardianship

In the event of incapacitation, judges generally appoint an evaluator (usually an attorney who will be paid from your assets) to evaluate the situation for the court. If the allegedly incapacitated person is found to be unable to make financial and/or health decisions, the court appoints a guardian (also known as a conservator) to make the necessary decisions for a specified time.

Usually the guardian is an attorney who has no clue how you would want your life managed. The guardian most often ends up just paying bills rather than making appropriate decisions that could incur liability. In addition, the court-appointed guardian will require payment for services from your estate, adding another drain on your finances.

You can imagine how expensive the procedure, and the resulting decisions, can be to you and your estate. Even worse, the guardian may be intrusive in your life and decide totally opposite to what you would want. It also depends on the state and the court as to whether the guardian can or would transfer your assets to satisfy Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Tip. Not only is a guardianship likely to be more expensive than creating the durable power of attorney described below, appointment of a guardian also entails public disclosure of personal matters and financial information. However, if you prefer to have court supervision of the guardianship with the additional protection that brings, and full disclosure to all interested parties, then rely on a guardianship and do not execute a durable power of attorney.

Preneed designation of guardian. In some states, you can execute a preneed designation of guardian, which designates your desired guardian in the event of need. Only judges can determine who the guardian will be, but they will generally follow your designation.

Section 6. The Durable Power of Attorney ↑↑↑

One method of avoiding a court-appointed guardian is by use of a durable power of attorney. A durable power of attorney is a type of power of attorney that is used for business and other affairs. Because it contains the magic word durable, it does not terminate if the principal (the person who executes the power of attorney) becomes unable to communicate or is otherwise incapacitated. It does terminate on death of the principal.

Powers can be effective immediately or, if the law of your state allows it, can be springing: the power “springs” to life when an event or events described in the power occur. For example, it could be stated that the power only becomes effective if and when you, the principal, become incapacitated.

The document can give the agent or some third party the power to determine when the principal has become incapacitated. This doesn’t mean your agent can just declare you incapacitated. The agent must start the process by asking your doctor to certify incapacity. An effective provision that balances the needs of the parties and timeliness would be to permit the agent to determine incapacity with the confirming advice (or agreement) of two physicians, one of whom is your attending physician. If you do not provide any instructions, a court may have to make the determination.

Tip. Provide in the power of attorney for a periodic reexamination of your capacity.

Powers can be general, or limited to matters specifically stated such as dealing with Medicaid or Medicare, signing checks or paying bills. Powers do not generally (and in some states may not) cover health, marital status, or testamentary dispositions. In a few states, a principal is allowed to delegate to the agent in the durable power of attorney various health care powers in addition to control over financial matters. In some states, such as New York, a health care power of attorney must be a separate document from a power of attorney used to manage the property and financial affairs of the principal.

To be sure the agent has all the necessary powers to take care of unforeseen matters, it is preferable to include a general list of important specific powers in addition to the ones specified in the state statute. Unless these powers are specifically mentioned, the agent’s actions may be limited to only the matters described in the statute. Consider giving your agent the power to

• change your domicile to a state where Medicaid rules are more favorable.

• access safe-deposit boxes.

• renounce or disclaim an inheritance and/or insurance proceeds. This could be useful for estate and Medicaid planning unless prohibited by state law.

• sign tax returns, sign IRS powers of attorney, and settle tax disputes in case of an IRS audit.

• deal with and collect proceeds from health and/or long-term care insurance. With respect to your life insurance policy(s): to take a loan against the coverage, to accelerate any death benefit, and even to sell the coverage.

• make gifts or continue a gifting plan that can be used to systematically reduce the size of an estate and thus the estate tax or to qualify for Medicaid.

• your right to revoke or amend the power of attorney itself.

Tip. To preclude any questions about your competency, when you execute a power, attach a letter from your attending physician stating that you are competent.

A power of attorney, like all of the other documents discussed in this chapter, can be revoked at any time. It is revoked automatically when the principal returns to mental competence or dies.

Tip. In some states the appointment of a guardian or other representative terminates the power of attorney. In those states, name the agent to also act as your conservator, committee, or guardian.

Consult with a local attorney before signing any power of attorney to be sure of the correct wording and effectiveness in the state in which you reside.

Whom to choose as an agent. Unlike in matters involving your health, where timeliness is usually important, you may consider appointing two or more people to act together as your agent for your nonhealth affairs. The decisions involved in business affairs are quite different from those involved with health, and the checks and balances that two people provide may be of value.

Copies. If you execute a durable power of attorney, execute up to six duplicate originals since many companies or organizations insist on having an original for their files. Also, go to your bank, your stockbroker, and any other financial institutions you deal with and get a copy of their power of attorney form. Although each of these companies would eventually accede to your form, they are likely to give your agent a needless hassle if your power is not on their form. They can also be expected to hassle over a power executed more than a few years ago, so it is best to re-execute this document every few years.

Tip. Whether required by statute or not, include the notarized signature of your agent or agents on your power. It is the authenticity of that signature upon which the person to whom the power of attorney is presented will be relying.

Section 7. Revocable Living Trust

For purposes of this chapter, it is only important to know that another alternative to guardianship is the creation of a revocable living trust. A revocable living trust allows you to be in control, while appointing a successor to take over if you become disabled. These entities are discussed in chapter 33, section 3.6.

I do not recommend creation of a living trust solely to avoid guardianship. However, it is an ancillary benefit to be considered when exploring the uses of such a device.

Section 8. Preneed Decisions Concerning Minor Children

By being prepared, you can control the situation in the event of your incapacity or death and assure that your children are taken care of in accordance with your wishes rather than those of a court-appointed guardian.

Tip. If you use any of the alternatives mentioned in this chapter, discuss with your potential choice for guardian your views on education, moral upbringing, religion, possibly nutrition and exercise, and any other matters of importance to you. Confirm your thoughts in writing so you do not have to rely on the person’s memory. Include relevant personal information about each minor—such as likes or dislikes, medical history, and school history.

8.1 Guardian for Children

One method of protecting your children is to petition the court to appoint a guardian now. This gives you the opportunity to present your version of why your candidate should be appointed. On the other hand, appointment of a guardian now means that you have to give up your legal rights to your children. While the children could live with you, and you can always ask the court to revoke the guardianship, no decisions could be made about the children unless you obtain the agreement of the guardian.

Standby guardian. In some states you can go to court now to have a person named standby guardian—which means the person doesn’t become guardian until a specific event happens, such as your incapacitation. In addition to the advantages of a guardian just discussed, there is the added advantage that the person is in place to start acting immediately if something happens to you.

Preneed designation of guardian. Another alternative in some states is to use a variant of the pre-need designation of guardian described in section 5, designating a person as a guardian for your children. It provides for the care of your children without your giving up custody now, since it does not take effect until (and only for as long as) there is a “need.”

Identifying the guardian. If your children’s other parent is alive and involved in their lives, that person would normally become the guardian. But if that person is abusive, estranged from the children, or is unfit, you will want to pick another caretaker.

When choosing a person to serve as guardian or substitute guardian:

• Many therapists suggest that the children be involved in identifying a guardian. In any event, this may be a good time for the children to spend more time with their potential guardian.

• Do you and the person share the same thoughts on raising children? Will that person follow your wishes?

• Does the person want to raise your children, and do they all get along?

• Does the person have the energy and resources to raise a child? Does he or she have a friend or family that can help out if necessary?

• If you are considering naming a couple as guardian, be sure to state what happens if they no longer live together. You don’t want your children to be the sad object of a messy divorce.

• Keep in mind the court will probably check to see if the person has any prior complaints filed against him or her, particularly concerning child abuse.

Tip. The other parent of your children has the right to request custody of them. To avoid a hassle, try to obtain the other parent’s written agreement to your chosen guardian. If that doesn’t work, or if even the request would be problematic, speak with an attorney about how to handle the situation.

8.2 An Adoptive Family for Your Children

If there are no appropriate family members or friends to care for your children if you die, consider choosing a “second family” for the children. Taking such an action now relieves stress for both you and the children. Children will be reassured that they will not be left alone or abandoned if you die. There are local programs to help parents find adoptive families.

An adoption has the following advantages:

• The children, once adopted, have the same right to support and benefits from the adoptive parents as if they were born to them.

• The adoptive parents do not risk losing custody.

Disadvantages:

• You lose all of your rights to custody of the children and to make decisions for them.

• The adoption may also add more stress to the children because it could be a constant reminder that a parent is ill and will probably be gone one day.

Adoption generally requires the consent of both parents if they are alive and have not abandoned the children. A court must approve the adoptive parent(s) and will probably conduct an investigation to make sure the person or people are fit to be parents. Adoption is permanent, while guardianship or custody may be temporary.

8.3 Foster Care

Foster care, placing your children with adults who will be responsible for them, without adopting them, is a fail-safe alternative if you are not able to care for your children and no other care is available. If you need financial assistance to keep your children out of foster care, or if you want to explore setting up foster care now, contact your GuardianOrg, a social worker, or your local welfare agency for advice.

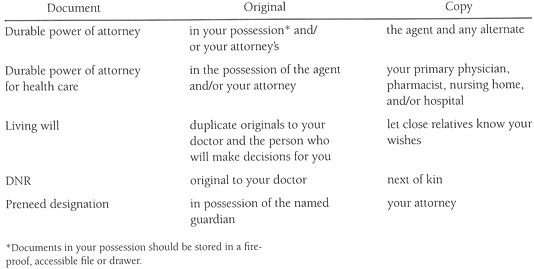

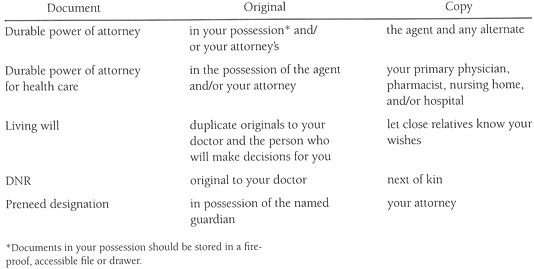

Section 9. Where to Store Advance Directives

Do not keep any advance directives in your safe-deposit box. They would not be accessible when needed. Preferably the documents should be kept as noted below.

Tip. Choice in Dying has an electronic living will registry. As part of the registration service, the organization will review your advance directive to verify validity. In case of a medical crisis, the registry will immediately fax a copy of your document twenty-four hours a day. The onetime registration fee is $45 for members, $55 for non-members.