MaPS-Teen Treatment Protocol

Mary Nord Cook

In an era of ever-decreasing inpatient and partial hospitalization stays, coupled with shrinking community resources, increasing numbers of patients need intensive outpatient behavioral health services that are readily accessible, convenient, efficacious, and cost-effective. There is a significant need for clinic-ready, manualized treatments for diagnostically complex, treatment-refractory youngsters, who present with a range of emotional and behavioral disturbances. A manualized Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) was developed at Children’s Hospital Colorado (CHCO) in January 2006, to serve a broad and diffuse patient population, aged 7–18 years old, referred on the basis of clinical acuity rather than primary diagnosis. To ensure standardization of service delivery and enable program dissemination, the written materials were deliberately evolved to be explicit and readily followed. To the best of our knowledge, no other published, manualized programs are available that target a broad and diverse patient population referred based on acuity, symptom severity, treatment refractoriness, and level of functional impairment, rather than diagnosis. Chapter 5 describes the psychosocial skills training protocols for the adolescent or teen CHCO IOP that served patients 12–18 years old. The child treatment protocols, targeting 7–12 year olds, and their families, were previously published in 2012.

Keywords

Treatment refractory; comorbid; diagnostically diffuse; parents; families; children; adolescents; teens; Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP); cost-effective; efficacious; manualized; evidence-based; standardized

Each Mastery of Psychosocial Skills (MaPS)-Teen session begins with introductions, brief check-ins, and a review of workshop guidelines. Use of the word “rules” should be avoided because it tends to invite resistance, especially among defiant youth. After their first week, teens are asked to share experiences from the previous week, related to their efforts toward completing “family homework,” which pertains to their self-identified individual and family treatment goals.

New Patient Orientation

During the first session or whenever a new teen joins the program, if using a “rolling” style of admission, orient them by providing a brief summary of the program format and components as well as topics or skill sets to be covered. New teens should already have been oriented to the program content, and organization, as part of a standard intake process that occurs prior to the first session, but inevitably they either endorse not having been oriented at all or to have forgotten some or most of their orientation. This has occurred, frequently, at our site, despite our intake clinicians routinely providing families with both verbal and written summaries, detailing program components and expectations.

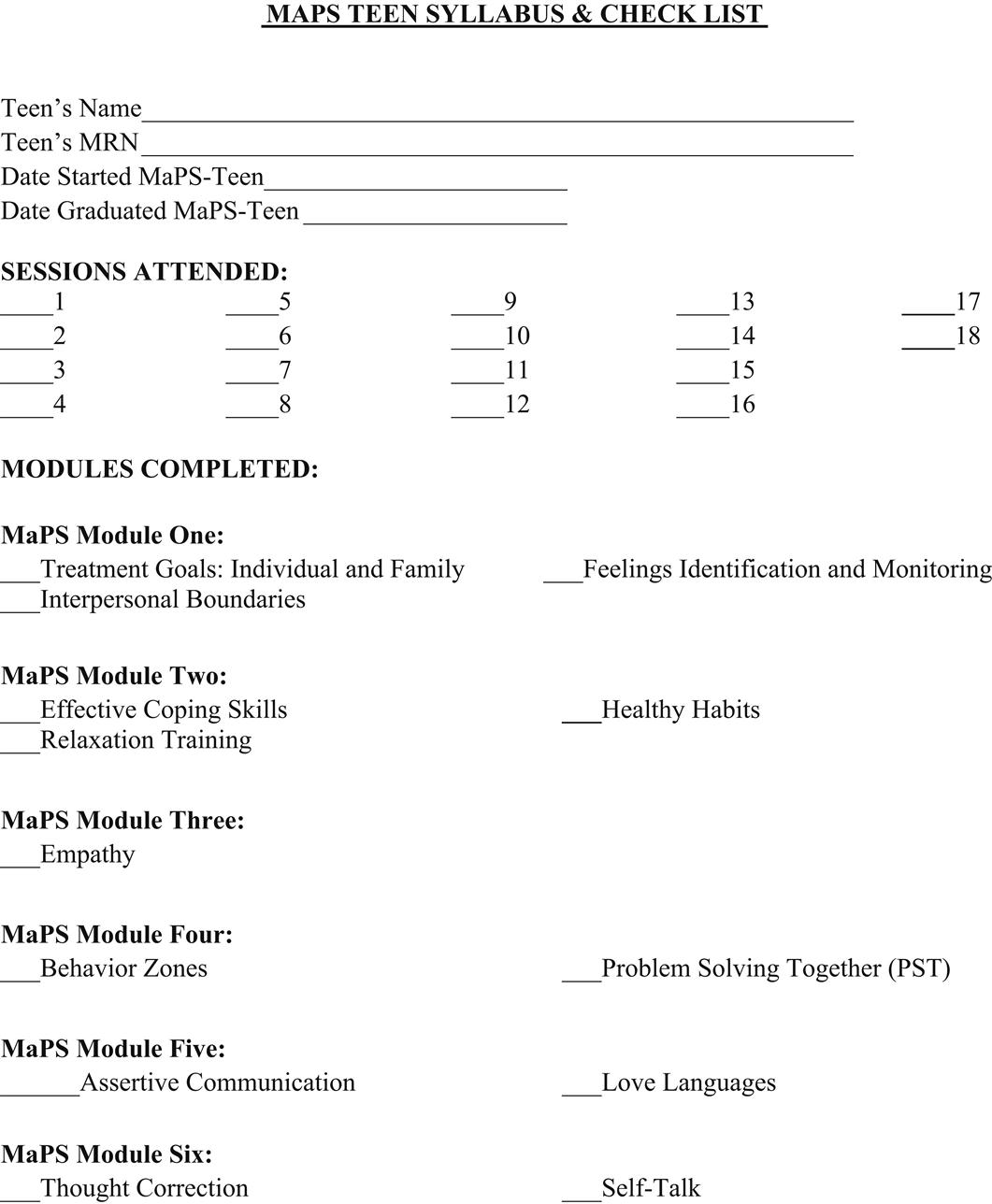

Have established teens assist with this process by inviting them to help welcome and orient new teens to the group, both around the content and process aspects. While reviewing topics or skill sets to be covered throughout the program, provide each teen with a copy of the MaPS’s syllabus to read along. Although not essential, if possible, print batches of handouts and worksheets in advance, and compile them into workbooks, which can be provided to new teens, rather than handing them out individual pages, one at a time. Loose, single sheets are more likely to get lost or tossed, whereas complete and bound workbooks have better odds of being saved and referenced in the future. The workbooks should be distributed to the group when needed, collected at the close of each session and given to graduating members to keep for good, at the point of program completion. If workbooks are used, it is better to only hand them out, when needed, because otherwise they can be distracting, tempting teens to leaf through them, even when they are not being referenced. Handouts pertaining to homework may be printed separately and distributed to the group to take home, at the end of each session. For the sake of convenience and to facilitate flexible use of the materials, all handouts and worksheets are available as separate forms, in the companion website.

Managing Teen Resistance

When teens first enroll in MaPS intensive outpatient program (IOP)-Teen, it is common for them to focus on trying to change their parents or other family members, such as siblings; initially, they often present with a defensive posture, and are prone to blaming and denigrating others, including their family members, peers, or teachers. Adolescents referred to the program often present with long histories of struggling with impulse control and mood dysregulation, perhaps habitually displaying maladaptive, unsafe, and aggressive behaviors. As such, it is not uncommon for these youngsters to have experienced failures or struggles in multiple domains of functioning, including peer and family relations and school. They may have been “scapegoated” by their family and school staff, and perceived as defiant, “disrespectful,” “lazy,” or “spoiled,” by significant adults in their lives. Persistent patterns of experiences of this nature inevitably lead to escalating levels of psychological defensiveness and externalization of blame, as common mechanisms for coping with feelings of inadequacy.

If teens are tending to blame their parents, other individuals, or circumstances for their failures or struggles, you may want to ask them, “What can you control?” The answer, of course, is that the teens can control how they approach and respond to their parents and others, as well as their behaviors, in general. However, because families can be understood as “closed systems,” in which changing one element will inevitably reverberate and effect change throughout the system, the power to modify their end of an interaction is often enough to effect the changes in response that they desire from their parents.

It is our experience that the most effective and powerful way to effect changes in an adolescent is to simultaneously and equivalently intervene with both the parents and the teen. If teens are focused on effecting changes on others, including their parents, they should be redirected to reflect upon and discuss strategies they might adopt, on their end, to elicit the types of reactions they are hoping to see in their parents and others, such as siblings. A question we frequently pose to teens, throughout the program, is “Is that behavior (or approach, or strategy, etc.), likely to get you what you want?” A theme of family empowerment, along with family ownership, is woven into every aspect of the program.

Icebreaker or “Fun” Question

Have the adolescents select and vote on a “fun” question that they also should answer during their introductions, which is intended to be playful and serve as an “icebreaker.” Examples of fun questions include, “Tell about a time you did something you wished you could take back,” or “Name your favorite summer activity,” or “If you could be an animal (or superhero), which one would you be and why?” or “What is your favorite book (movie, band) and why?” The fun question during the introduction additionally provides the clinicians with a way to assess where the youngster is at emotionally for that day, as well as spark meaningful conversation on an interest, strength, or life challenge for which the teen is seeking support or guidance.

New Patient Introductions

It is best to keep introductions and check-ins for all patients, new and established, short, as not uncommonly there are youth who are so exasperated or hungry for attention, that they attempt to ventilate at length (despite the clear structure and directive about introductions provided at every group’s onset). This behavior may be experienced by the other teens as counterproductive and “boring.” Many teens, especially those who present for treatment, have been struggling with establishing and maintaining appropriate interpersonal boundaries. They may be prone to “over-sharing” and divulging often irrelevant and/or explicit details about their private lives, despite group facilitators proactively setting limits to prevent such behaviors. Youth with these tendencies sometimes need substantial and firm redirection so that the workshop can focus on topics of interest and benefit to the entire group.

Go around the room and ask each new teen to identify him- or herself by first name only; mention his or her age, grade in school, and who lives in his or her household. Next, have new teens first identify one of their “strengths,” followed by one “challenge” with which they are currently grappling. Because teens often initially struggle to identify their strengths, explain that strength could be anything from “I’m a good listener” to “I’m a good tennis player.” Adolescents with histories of emotional and behavioral problems are often surprised and ill-prepared to be queried about and report upon their strengths. Many in our programs have endorsed that the inquiry during the check-in and introduction process is the first time they recall having been asked about positive qualities they possess, in a long line of involvement with behavioral health providers and services. They find it refreshing but are often taken aback.

Then, have each teen identify a “feeling word” that best describes his or her current emotional state. Emphasize the distinction between a feeling word and a physiological or physical state (e.g., “calm” or “content” would be examples of feeling words, whereas “tired” or “hyper,” would be examples of physical or physiological states). Finally, invite them to answer the “fun” question they selected for the current session. Once all new patients have had an opportunity to introduce themselves and complete their check-in, ask the returning teens whether or not the challenges mentioned by the new teens resonated for them, in reference to their own families. Encourage at least one or two of the established group members to relate a commonality, tied to the challenges reported by new members, with respect to their own current or past experiences and concerns.

Established Patient Introductions and “Check-Ins”

Ask returning or adolescents who are already established participants in the program, to introduce themselves by first name, answer the “fun” question and then identify a “feeling word,” reflecting their current mood. Invite them to briefly summarize the skill sets on which they are currently focused, together with their families. Cue them to verbalize both their current individual and family treatment goals, and comment on progress made toward goals. If attending their second session, they should have their completed goal worksheets handy, which they can be invited to reference during this section. You can provide established teens with the format of relating a “victory” (required), and a “challenge” (optional) that occurred since the last session inclusive of an experience during which they attempted or practiced a relevant skill, recently covered in the program. New patients were instead asked about “strengths,” rather than “victories,” to cue them to reflect upon and comment on themselves more globally, whereas established patients are cued instead to relay specific interactions or events, pertaining to the program content and their treatment goals. If they relate an example of an unsuccessful effort at deploying new skills, encourage them to reflect, together with the group, regarding explanations for the struggle or failure. Invite them, along with their peers, to strategize about approaches that might increase the odds of success in the future. Encourage returning or established teens to additionally relate an example of a skill or topic that has been particularly helpful to them thus far and the reasons.

Workshop Guidelines

Once introductions and “check-ins” have been completed, for new and established teens, facilitate a brief discussion of guidelines for the workshop, such as “start on time and finish on time,” “listen when others speak,” “stay on topic,” “use respectful language,” “turn off and put cell phones and other electronic devices away,” and of course, “maintain confidentiality.” Make the point that part of maintaining confidentiality means that while they are enrolled in the treatment program, they must refrain from developing personal relationships that transpire outside of group sessions. This point should be made explicitly and despite doing so, patients may still covertly develop friendships and even romantic connections, while in program, that sometimes become inappropriate and distracting. Many teens referred to such programs struggle with maintaining balanced interpersonal boundaries and often rush relationships, in a desperate effort to make peer connections and feel liked and accepted. Therapists can’t control whether or not this happens, but they certainly can and should make the point explicitly, that personal communications with group peers, outside of sessions, is contraindicated, at least while in treatment.

Ensure that these guidelines are restated and reinforced at the start of every session throughout the program and invite established teens to take the lead, in reviewing these with new members. If the guidelines are not continuously repeated, at the start of every session, inevitably one of the teens will begin using their electronic device or phone during a session, use foul language, or develop a pattern of coming late or leaving early. The frequent and repeated review and reinforcement of these simple, but fundamental behavioral expectations for the group, as part of routine check-in every session, is generally effective in preventing such disruptions. If teens display some form of acting-out behavior, without having been sufficiently oriented to the guidelines, it is much more difficult and shaming, to call them out and set new limits for their behavior, versus having already set clear and specific expectations proactively, in advance.

The need for confidentiality typically is worded, “What is said in here stays in here,” and has been playfully termed “The Vegas Rule.” Encourage adolescents to share with their parents regarding activities and concepts learned in the workshop but not to share specifics about what another peer said or did. They can share examples of things that were said or done, but cannot mention any patient identifying information, such as full names, ages, descriptions or other specific details, that could tie specific statements or behaviors to a particular person. It is important to note exceptions to confidentiality involving safety concerns (e.g., suicidality, homicidality, abuse) and repeatedly review them, when new members join, as a matter of routine orientation.

Workshop Format, Past Topic Review, and Family Homework

Each MaPS-Teen session should follow the same pattern, comprised of orienting new members, performing introductions, and reviewing workshop guidelines. The overarching topic of focus for the current session should then be mentioned, and the schedule for the day should be written on the dry erase board with time allocations specified for each section. The program should be continuously oriented by the syllabus, which is distributed to new members on their first day. Before launching into new material, it is useful to offer a mini-review of the previous session, taking no more than 10 minutes and calling on teens, to relate their recollections.

An interactive, experiential, and psycho-educational-style workshop is facilitated, each session, covering specific topics or skill sets, as outlined by the syllabus. The clinicians use a method of psycho-educational and Socratic teaching in conjunction with empathic and reflective listening, to inspire adolescents to ponder and brainstorm, about themselves, their families, and their peers. The facilitators should avoid, where possible, directly advising or directing teens, and instead, pose clever questions or make reflective, observational statements, that stimulate thinking and discussion within the group. The therapists should continuously work toward enhancing the sense of personal ownership and accountability, assumed by the teens, who may initially present in a hostile, defensive, or blaming manner.

Homework is assigned for all of the sessions, sometimes involving interpersonal interactions or activities and other times paper-and-pen exercises. Many homework worksheets and handouts are available on companion website and can be provided to the teens, as needed, at the close of the corresponding session. It is ideal to provide the participants with a 5-minute break at about the halfway point of each session; juice and snacks can be provided during this time.

“What About Me?” Examples

After every major topic or skill set, it is worthwhile to pause and invite the group to share and discuss examples from their own lives that relate to the topic covered in the current module. Encourage the teens to share either relevant victories or challenges; either type of scenario can provide teachable moments.

Handouts and “Business Cards”

During each session, provide the group with handouts, pertaining to the module being covered that day, at appropriate junctures during the session. Each module contains a series of handouts, which are available on companion website. Handouts which contain worksheets are given, as needed, to perform the “in session” exercises. Handouts reviewing the material covered or serving to cue homework should be distributed at the end of the session, for teens to take home. If workbooks have been compiled in advance, they should include all handouts and worksheets, aside from those needed for homework, to be completed in between sessions.

If workbooks have not been assembled by the clinicians in advance, advise the teens to keep their handouts together, in a safe place at home. Encourage them to maintain all handouts in a protective folder, or notebook, for future reference. Most modules also contain “business cards” reviewing material as well, which may be cut out, and provided to teens during the workshop to serve as a reminder. The teens may also be given copies of the “business cards” to keep, to tuck in their wallets and save for future reference.

MaPS-Teen Workshop Summary Outline

Materials Needed

New Patient Orientation

• Summarize program format, components, review syllabus.

• Distribute workbooks if using preassembled, bound sets of handouts.

• Alternatively distribute individual handouts during the session, as they come up during session and are actively being discussed and completed, or at end of session, as indicated.

Introductions, Check-Ins, and Icebreaker Question

• Have established teens assist new patients during check-in and promote a brief discussion on program format, content, and workbook.

• Taking turns between sessions, have one teen volunteer a “fun” or icebreaker question. Examples include the following: “What is your favorite band (animal, sport, etc.) and why?” “If you could be an animal, which animal would you be and why?”

• Encourage eye contact with peers and appropriate vocal tone and projection prior to each adolescent introducing him- or herself.

• Ask each teen to provide the following information:

– Briefly summarize primary treatment goal/s, skill sets they are focusing on.

– Briefly relay a victory (required) and challenge (optional).

– Ask established group members to relate commonalities with new teens, especially in regards to the challenges that were shared.

Guidelines

• Brainstorm workshop guidelines with the teens. A sample list might include the following:

• Listen when others are speaking.

• Do not raise your hand while others are speaking.

• Turn off all electronics, including cell phones, iPods, iPads, etc.

• Keep what others share during the workshop confidential, with the following limitations:

– Facilitators would need to break confidentiality if (i) you are hurting someone else, (ii) someone else is hurting you, or (iii) you are hurting or have plans to hurt yourself.

• Convey that it is okay to tell your parents what you did or learned in workshop but not what other teens said or did because that is their personal business.

• Part of maintaining confidentiality includes refraining from communicating with group peers, outside of sessions, while enrolled in the program.

Review/Current Session

“What About Me?” Examples

Wrap Up and Answer Questions

Handout/Business Cards

Module 1 MaPS-Teen Teen Handout #1

MaPS-Teen Module 1

Introductions and Guidelines

Begin Module 1 of the MaPS-Teen program with an orientation if there are new members, introductions, “check-ins,” and a review of workshop guidelines, as detailed in the MaPS-Teen Orientation, Introductions, Guidelines section. Follow the same basic routine at the start of each session. After introductions and “check-ins” are completed, mention the overarching topic of the current session, and write the schedule for the day on a dry erase board, with time allocations specified for each section. Distribute MaPS-Teen Module 1 program syllabus to teens on their first day. If there are new teens, take a few minutes to discuss the program syllabus, including highlighting and briefly describing the topics or skill sets to be covered, throughout the program. For subsequent sessions, review these elements as needed for new members, including providing them with copies of the program syllabus, along with recruiting established patients to welcome and briefly orient new ones. It is ideal to provide the participants with a 5-minute break at about the halfway point of each session; juice and snacks can be provided during this time.

Icebreaker Exercise

At the start of each session, immediately after orientation of new members, but prior to introductions and check-ins, have the teens brainstorm and then vote on a “fun” or icebreaker question. Have group members answer the question, at the end of their introductions. This is completed to assist teens in getting to know one another and enable them to be less guarded and more comfortable.

Review

Once introductions have been made, guidelines have been reviewed, and the current session’s topic mentioned, conduct a brief review of material from the previous session for no more than 10 minutes, challenging established teens to recall previously taught skills or information.

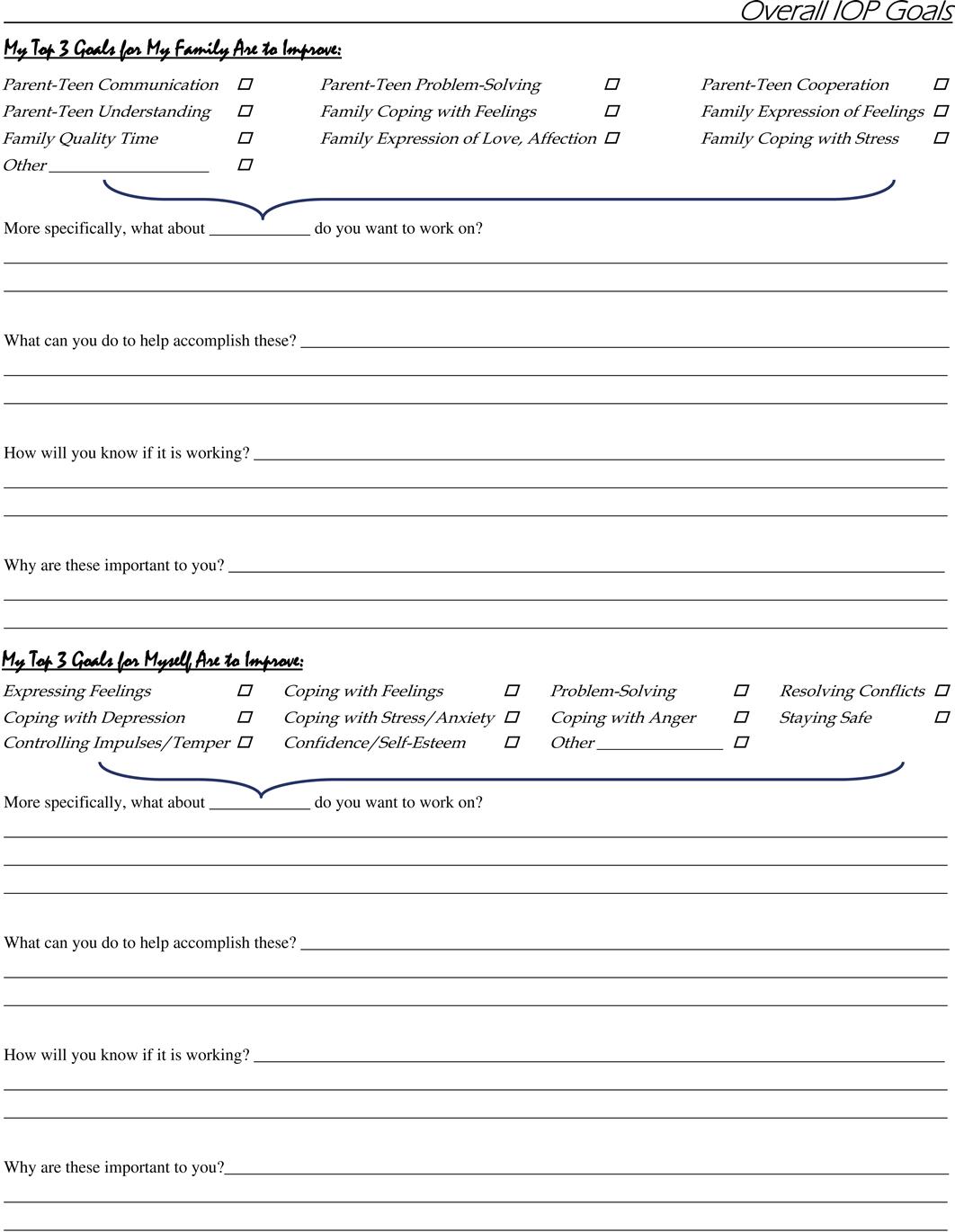

Treatment Goals: Individual and Family

Throughout the program, there is an emphasis on clearly and concisely articulating primary treatment goals, for each individual, and their family. Ask adolescents to identify both an individual and family goal, during their first session, which must be connected to the topics or skill sets covered in the program. When the expectation of formulating goals which are highly relevant and specific to the program is not made clear, it is very common for youth to identify treatment goals that are irrelevant, unrealistic, or vague, such as “I want to be a better dancer,” or “I’d like my father to move out.”

Their peers in group and therapists may assist with formulating and potentially reframing, specific treatment goals, if needed. As new adolescents share their experiences and reasons for entering the program, they can usually be readily guided to formulate specific treatment goals, which tend to flow naturally from their past experiences, including both challenges and victories. Additionally, the teens are expected to formulate and relay to the group, their ideas and plans for achieving their self-identified treatment goals.

During subsequent sessions, as part of routine check-ins, invite teens to discuss their progress in relation to each of these goals. A treatment goals worksheet should be provided to new group members at the end of their first session, and they should be advised to further contemplate and write down their individual and family goals at home, prior to the next session. The worksheet contains several explicit directions and cues, which help teens focus on goals that are relevant, measurable, and realistic. Returning teens should have completed their goals worksheet, which they may be cued to reference, throughout the program, during “check-ins.”

The adolescents are repeatedly urged to identify and comment on their own strengths and challenges throughout the program as well, which may impact goal attainment, positively or adversely. Treatment goals can be established during Module 1 or the teen’s first session, if using a “rolling” style of admission, but are typically dynamic and evolve throughout the course of the program, as each family masters various skill sets and achieves behavioral and relationship targets.

Feelings: Good, Bad, and Ugly Ones

Feelings Overview

Ask the group whether they think emotions are important, and then cue them to identify whose feelings they consider important. Typically, they will conclude that yes, feelings are important and that everyone’s feelings are important, at least to the person having them and those who care about that individual. Focus some discussion on negative or uncomfortable feelings, encouraging the adolescents to reflect upon and brainstorm a few emotions they personally find uncomfortable, difficult, or distressing. Invite them to share which emotions tend to cause the most problems or “get them in trouble,” and to then elaborate upon the reasons.

Youngsters who struggle with regulating emotions and controlling impulses often come to view emotions, especially forms of anger, as “bad”; they often likewise may come to view themselves as “bad” for frequently expressing their emotions in an ineffective or even destructive manner. Because many of the youngsters enrolled in the MaPS IOP-Teen program have histories of being extremely reactive to emotions, and additionally often live in households wherein family members, including parents, may have modeled ineffective or aggressive expressions of emotions, learning to regulate and express emotions appropriately, is often a focus of treatment for many families.

Using a psycho-educational and Socratic style of teaching, ask questions about emotions, with the goal of helping the group recognize and acknowledge that experiencing a full range of emotions is perfectly normal and, in fact, unavoidable. Generate discussion to help the teens recognize that feelings are not good or bad—they just are—and that it is normal to experience anger, along with a full range of other emotions, on a regular basis. Assist the group in recognizing that all feelings are part of the human experience and serve important functions.

Facilitate discussion regarding how emotions, even uncomfortable or difficult emotions, are often expected or understandable. Have the adolescents provide examples of when this might be the case. The goal of this discussion is to guide the group to recognize that their emotions serve a purpose and can often fuel positive, appropriate change. An example the teens might suggest is becoming angry in response to a bully mistreating a peer, propelling them to inform a teacher for the sake of protecting the victim and eliminating the bullying. An additional example might include instances during which citizens become outraged enough about an injustice that they are energized and mobilize to try to make things right and effect positive change. Depending on the examples the adolescents themselves are able to generate, you may want to contribute well-known examples from history such as the actions of Rosa Parks, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

While acknowledging that all feelings are normal and acceptable, in and of themselves, ask the group to discuss whether or not behavioral responses or reactions to emotions should be managed or limited. It is important to reiterate and reinforce the point, through stimulation of didactic discussion, that unmanaged or inappropriate expression of emotions can be destructive, hurtful, and wrong. On the contrary, help the teens realize the point, that if feelings can be proactively monitored, labeled with words, discussed, and processed, they can be understood and managed in healthy, adaptive ways, rather than destructively acted out. The goal is for the teens to learn to monitor their feelings; appropriately identify and label them; and then master expressing them in safe, nondestructive, nonhurtful ways.

Ambivalence or Mixed Feelings

Facilitate discussion regarding the potential for experiencing two or more different conflicting emotions at the same time, by asking the group, “Is it possible to feel happy and sad at the same time?” Or “Is it possible to feel angry and hurt at the same time?”, “Is it possible to be mad at someone and love them at the same time?” Ask whether more than one emotion or even seemingly conflicting emotions can be experienced simultaneously. Guide the group, through Socratic discussion, to recognize that emotions, like people and relationships, are complicated and that often individuals experience a variety of overlapping or even conflicting emotions simultaneously.

Foster additional discussion among the group regarding the phenomenon of ambivalence in relationships. Ask the teens whether they know what ambivalence means, and cue them to formulate an adolescent-friendly definition, such as “a mix of bad and good,” or “mixed feelings.” Help the adolescents recognize and accept that everyone feels anger occasionally, even toward people they love very much. Generate discussion regarding the fact that all relationships and all people are a mix of good and bad. Make the point that just because people sometimes feel angry, including toward people they love, does not mean that they are bad people or that they do not love those at whom they have been angry. Inform the group that while experiencing intense emotions, all human beings may sometimes experience fleeting thoughts or even wishes to harm others; as individuals age and mature, however, they learn to control their impulses and refrain from acting out aggressive thoughts or fantasies.

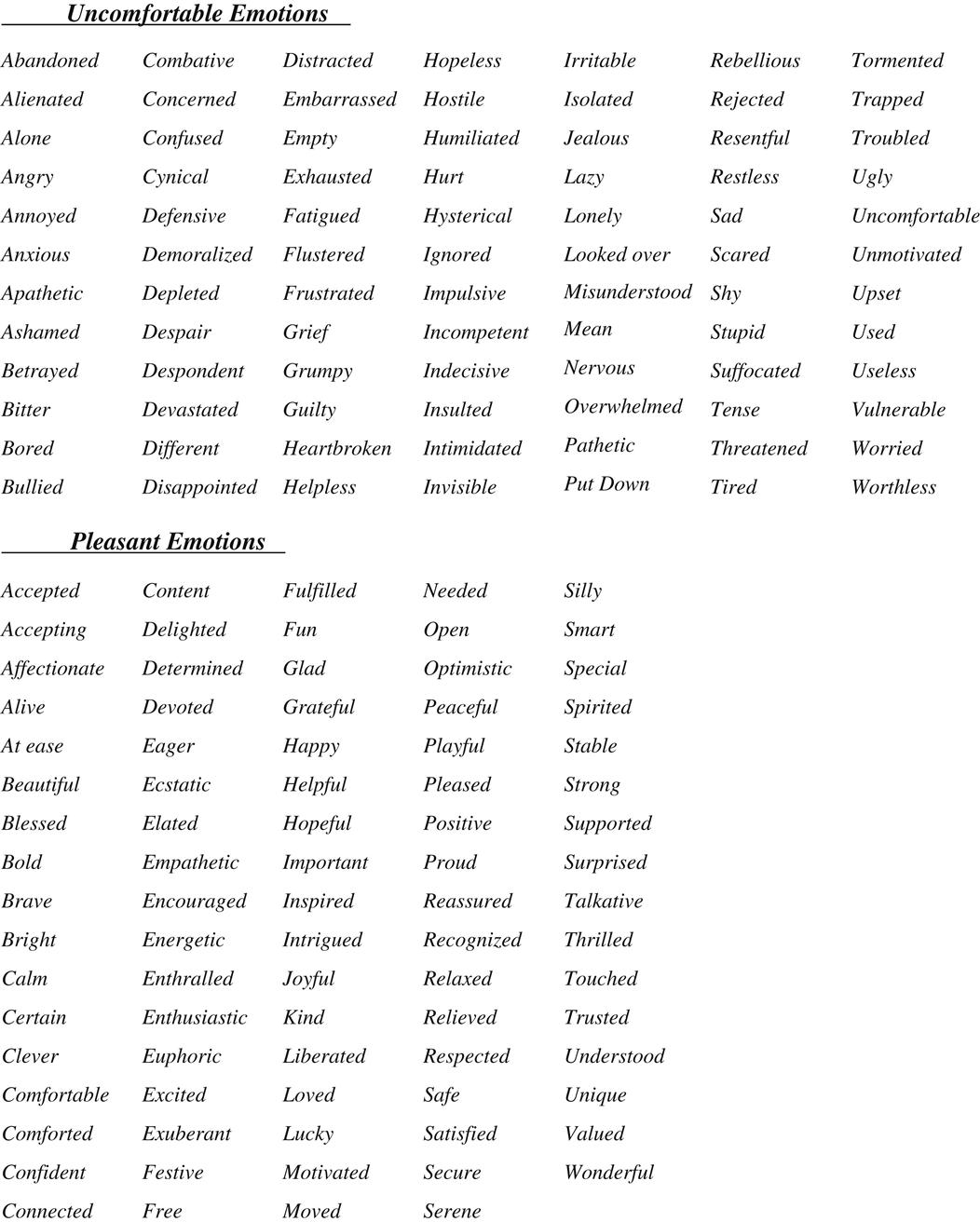

Feelings Vocabulary

Reference the earlier point, that when feelings are aptly labeled and discussed, they can be understood and effectively managed, and then invite the group to brainstorm a list of feeling words, which can be written on a dry erase board. Again, remind the teens to distinguish feelings from physical or physiological states, such as “hyper,” “tired,” or “sore.” Additionally, help them discern the difference between feelings and thoughts, perceptions or judgments. For example, teens might relate feeling as though “my family situation is hopeless,” when asked to reflect upon their feelings, although that statement is more representative of a thought or viewpoint, rather than indicative of an emotion or feeling state. The term “hopeless” by itself could represent a feeling state, but not when used as a descriptor referencing a family situation.

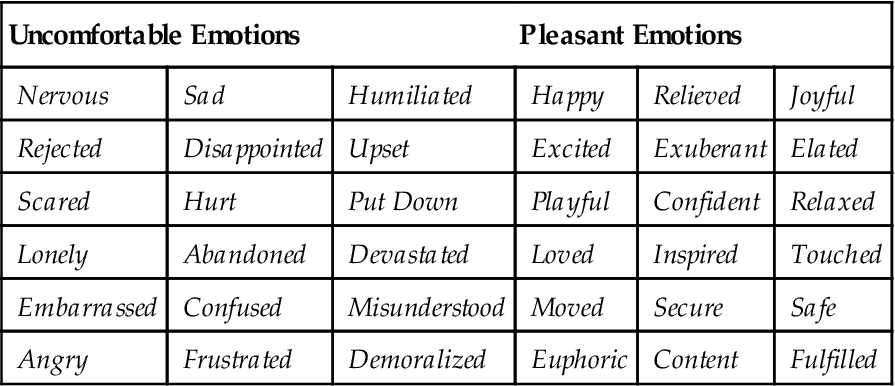

It is helpful to have the teens initially focus on more positive or pleasant emotions and then switch and instead brainstorm another list, comprised of more uncomfortable or unpleasant ones. The lists generated, which can be subsequently augmented via input from the therapists, might resemble those that follow:

| Uncomfortable Emotions | Pleasant Emotions | ||||

| Nervous | Sad | Humiliated | Happy | Relieved | Joyful |

| Rejected | Disappointed | Upset | Excited | Exuberant | Elated |

| Scared | Hurt | Put Down | Playful | Confident | Relaxed |

| Lonely | Abandoned | Devastated | Loved | Inspired | Touched |

| Embarrassed | Confused | Misunderstood | Moved | Secure | Safe |

| Angry | Frustrated | Demoralized | Euphoric | Content | Fulfilled |

Feeling Intensities

Have the group define intensity of feelings, which can be summarized as how little or how much you feel a feeling. Introduce the group to a scale, 0–10, and invite them to begin routinely noting their feelings, as well as assigning an intensity percentile.

Feelings Identification and Somatic Monitoring

Ask the teens to take turns identifying and relating their top two or three most uncomfortable, difficult, or distressing feelings and why they tend to cause problems in their lives. Encourage teens to identify warning signs for their emotions to include both physiologic or bodily sensations, as well as behavior changes or signs observable by others that indicate they are experiencing that particular emotion. Questions such as the following may be posed, to generate fruitful discussion:

How do you know you are experiencing that particular emotion?

How do you differentiate between feeling anxious versus feeling excited? (This is an example of a question used because the two feelings can physically be similar.)

Where in your body do you feel sadness (hurt, anger, etc.)?

How do you know you are becoming sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

How would you describe the sensation of feeling sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

What changes do you notice in your body, when you begin to feel sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

Some examples of physical sensations or bodily effects noted, in association with various feelings, include the following list:a

Differentiate between physiological changes, such as the list above, versus behavioral warning signs which might include:

Facilitate discussion regarding the mind–body connection and help the group recognize regarding that there are physiological and bodily reactions that typically accompany all emotions, which can vary between individuals. Help the adolescents appreciate the value of identifying and attending to their bodily and behavioral warning signals, as early as possible, related to impending and escalating feeling states. Guide them to recognize the window of opportunity for self-soothing and effective coping that can be leveraged, before impulsive or harmful responses take over. Stimulate discussion with the group regarding the fact that many people find it difficult to deescalate their feelings and emotional reactions before they act out in some manner (again, the normalizing works really well). The goal is to learn to proactively identify their own triggers and bodily signals and attenuate them early. As youngsters become more tuned into their body signals, they can become better at taking care of themselves and dealing with their difficult emotions and the precipitants, before they react impulsively in a manner they and those around them might regret.

“Fight-or-Flight” Response

Generate discussion regarding the phenomenon of fight or flight. Encourage the teens to discuss what they know about the phenomenon of the fight-or-flight response and its origins. The response consists of elevated arousal; increased heart rate, pulse, and breathing; increased strength in large skeletal muscles; and shifting into a highly instinctive, primitive state of mind (residing in the amygdala) that is bent on survival. Blood rushes to the major vital organs including the heart and lungs and to large skeletal muscles but notably away from the frontal lobes and rational decision-making parts of the brain (prefrontal cortex). Thus, a person experiencing a fight-or-flight response might feel dizzy, lightheaded, or confused. This response is a vestige of cavemen times, when early man had to be on guard and have the capacity to launch instantly into a physical state in which he was prepared to run away or fight when faced by that saber-toothed tiger or woolly mammoth. Ask the teens “What happens to people when they feel threatened or experience the fight-or-flight response?” and write down the ideas they generate on the dry erase board. The list should ultimately resemble the following:

Increased blood flow to large organs

Increased blood flow to large skeletal muscles

Facilitate discussion with the adolescents regarding the fact that arousal states (along with all emotional states)—as most people know and have experienced—are usually contagious. That, too, probably conferred early evolutionary advantage and so it has been preserved in the species. It is rare, however, that the fight-or-flight response is apropos in modern society. People no longer face saber-toothed tigers or their modern-day equivalent. Unfortunately, many youngsters are “sensitized” to enter this high-arousal state with minimal provocation. Their central nervous system wiring is behaving as though “short-circuited” and vulnerable to misfiring out of cue. In fact, there is a burgeoning body of literature, growing out of functional brain imaging studies, that is amassing evidence demonstrating a pattern of amygdala hyperactivation (emotion) coupled with prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate (rational decision-making) hypoactivation, in adults and youngsters with anxiety and mood disorders (Wegbreit, Cushman, Puzia, et al., 2014). This robust scientific finding can help answer teen inquiry as to “Why am I struggling with emotional regulation?” Their parents or siblings may likewise be sensitized and extremely reactive to their escalations, as interactional patterns can become deeply entrenched and essentially automated.

Greene (2001) suggests that youth lose at least 30 IQ points when they become hyperaroused. They become more primitive and less capable of rational, logical, reasonable thought and conversation. If their parents likewise become hyperaroused, it is as though gasoline has been poured on a fire, with both parties operating in a primitive, low-intellect, aggressive state. Ask the teens to reflect on an instance during which they entered this high-adrenaline state themselves. Encourage them to recollect the event in vivid detail and to share highlights with the workshop. Ask, “When highly aroused, what becomes of one’s ability to think clearly, to reason, to negotiate, or to problem-solve?” A hyperaroused person loses much of his or her capacity for rational thought along with 30 IQ points and instead becomes braced for action, either defending against or evading danger—a primitive being. Their higher-level brain functions shut down, leaving only the most primitive part of the brain functional and engaged. You might orient the group to reference the psychological mindset of a threatened individual as being controlled by their “Savage” brain (amygdala, brainstem) which is more powerful but much dumber than their “Civilized” brain (frontal lobes or prefrontal cortex). The former is comprised purely of brute force, but lacking intellect and capacity for reason. The latter is admittedly less powerful, but much, much more intelligent, effective, and mature!

Feeling Triggers

Invite the group to recall examples of past experiences involving uncomfortable feelings, in a broader sense, and to elaborate upon the circumstances under which those emotions were elicited. As individual teens share examples, inevitably their peers will identify and point out parallels from their own lives. Encourage the adolescents to especially reflect upon what kinds of events set them off. Through didactic discussion, make the point that every individual will perceive the same situation differently and that different stimuli make different people angry.

It is very common for adolescents to identify interpersonal stressors as their most common and intense trigger for intense distress. That finding is often associated with difficulties in maintaining healthy and balanced interpersonal boundaries, as detailed in the next section. Teens especially are prone to becoming overly dependent upon validation from peers for self-worth, as well as prone to failing to preserve their own definition of self as separate and distinct from others. Hence loss of friends or romantic break-ups can trigger catastrophic reactions in adolescents who are left feeling empty, worthless, and devastated. Similarly, teens with ill-defined identities are likewise vulnerable to disintegrating emotionally in the face of intense conflict and verbal assaults, laden with derogatory labels and put downs from family members, including parents and siblings.

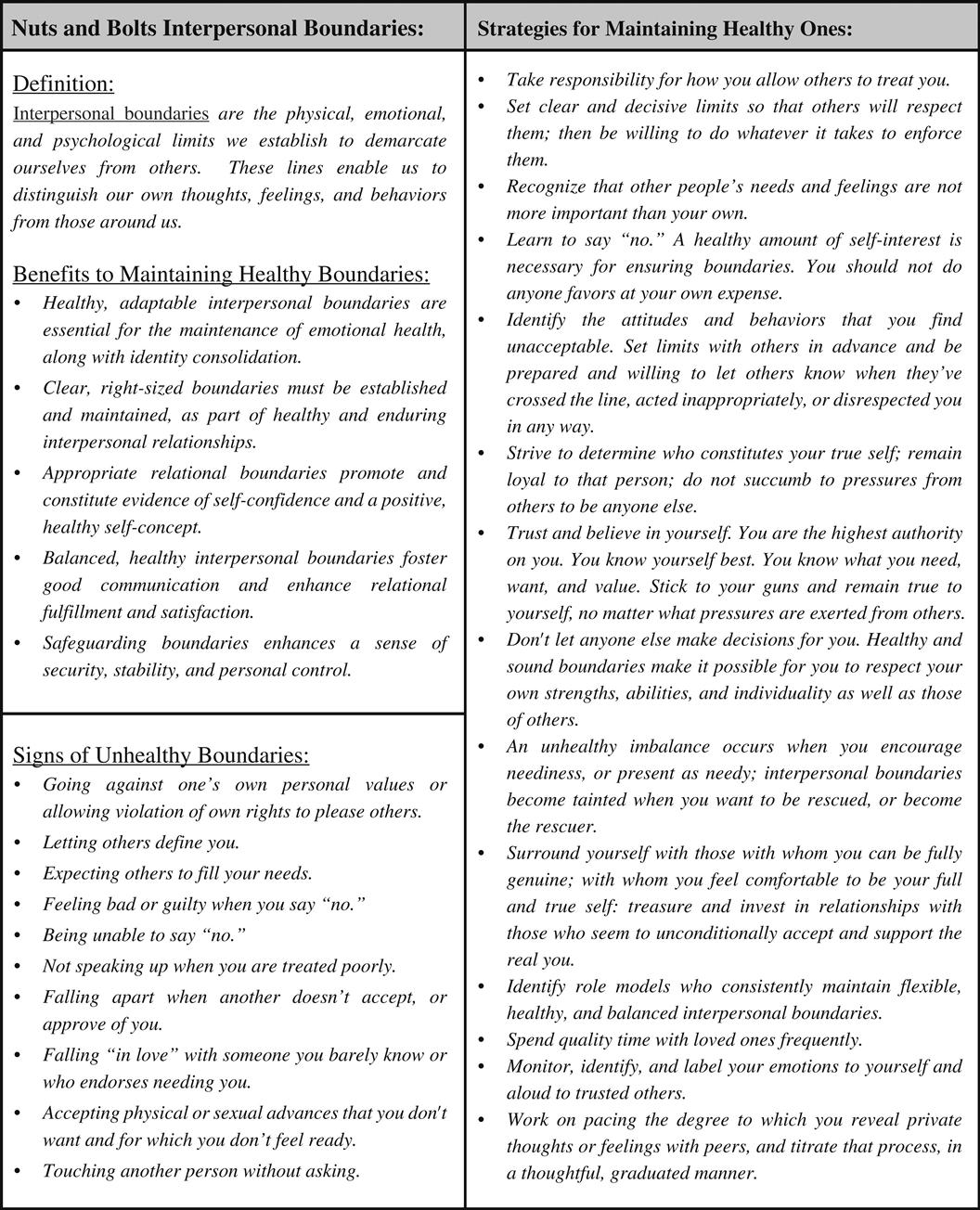

Interpersonal Boundaries

It is well established that the most salient and critical developmental task of normal adolescence is identity consolidation, most especially in regards to defining oneself, in relationship to others (Stiles & Raney, 2004). Typically developing teens shift their focus and prioritization of interpersonal relationships from parent–child to peer–peer (Flannery, Torquati, & Lindemeier, 1994). Within this context of heavy reliance upon peer acceptance and relationships, a fundamental interpersonal skill must be honed, pertaining to the capacity to healthily balance forging positive connections with peers with psychological autonomy (Scott & Dumas, 1995). The case has been made, via a significant body of literature that interpersonal boundaries that fall toward the extreme ends of the spectrum, ranging from extremely open to totally closed, are problematic and contribute to maladaptive social and psychological development, as well as fuel emotional and behavioral struggles (Peck, 1997).

Many teens, who have had difficulty making and keeping friends and/or have been embroiled in intense and chronic family conflicts, are inept at managing interpersonal boundaries. They often exhibit patterns of rushing hastily into relationships at mock speed, in an intense, forceful, and emotionally dependent manner, characteristically revealing their whole life story at a first meeting, or instead refusing to open themselves up to engaging even superficially with peers.

Stimulate a discussion with the group about interpersonal boundaries. Invite them to define that term, as well as define the terms “identity formation” and “sense of self.” Guide them to arrive at roughly the following definition:

Interpersonal boundaries are the physical, emotional, and psychological limits we establish to demarcate ourselves from others. These lines enable us to distinguish our own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors from those around us.

Ask them to ponder extremes of interpersonal styles, ranging from extreme openness, on the one hand, contrasted with extreme withdrawal and impenetrability, on the other. Ask them for examples of experiences wherein they observed interpersonal boundaries that were too loose or fluid. Guide them to recognize the pitfalls and dangers inherent in maintaining relationship boundaries that are too diffuse, whereby one individual loses their distinct identity or sense of self and instead merges or becomes “enmeshed” with another individual. Diffuse boundaries can be seen in any relationship including inside professional situations, families, friendships, and romances. Ask them to reflect upon experiences wherein they observed an unhealthy degree of interpersonal walling off or impenetrability and invite them to consider and discuss potential risks inherent to that extreme style of relating. Ask them to consider the following examples:

• Your significant other is pressuring you, more and more, to give up time with your family and abandon your other peer friendships.

• Your group of friends is fiercely pressuring you to style yourself in a manner that consistently conforms to their patterns of dressing, accessorizing, and wearing of hair and make-up.

• You find yourself unable to tolerate ever being alone and on an emotional roller-coaster that is dictated by the degree to which you perceive acceptance and approval from peers.

• You struggle to make decisions independently and never seem to be able to form an opinion or make a choice, on your own, without first consulting one or several peers.

• You are unable to tolerate being single, even for a few weeks, and do not feel content or complete, unless in a committed, romantic relationship.

• You find yourself changing friend groups often and each time, you adopt a new style, demeanor, values, musical taste, and interests/hobbies.

Cards with sample scenarios listed, are available in the “Therapist’s Toolkit,” in the book’s companion website. Have the cards cut out and the group take turns pulling out and reading a scenario aloud. Ask the individual to first respond to the scenario and describe any concerns or inferences. Encourage the individual, with help from the group, to brainstorm potentially healthy and effective options for addressing the situation described.

Facilitate discussion around the value of striking a balance between remaining separate and distinct, psychologically, from others, versus allowing one’s definition of self and self-worth to be utterly dependent on feedback from others. Provide psycho-education regarding what is known in reference to optimal adolescent psychological development and social success, that is, that flexible and balanced interpersonal boundaries promote well-being and healthy relationships. Make the point that the capacity to define oneself is in part contingent upon one’s capacity to form relationships with others, wherein a connection develops, but at the same time, both individuals retain their distinct and separate identities. Invite the teens to share specific examples regarding interpersonal struggles they’ve experienced and brainstorm options for developing and maintaining healthy and flexible interpersonal boundaries, while consolidating a sense of self. Examples of strategies for promoting appropriate interpersonal boundaries and consolidation of identity or sense of self include the following:

• Take responsibility for how you allow others to treat you.

• Set clear and decisive limits so that others will respect them; then be willing to do whatever it takes to enforce them.

• Recognize that other people’s needs and feelings are not more important than your own.

• Learn to say “no.” A healthy amount of self-interest is necessary for ensuring boundaries. You should not do anyone favors at your own expense.

• Identify the attitudes and behaviors that you find unacceptable. Set limits with others in advance and be prepared and willing to let others know when they’ve crossed the line, acted inappropriately, or disrespected you in any way.

• Strive to determine who constitutes your true self; remain loyal to that person; do not succumb to pressures from others to be anyone else.

• Trust and believe in yourself. You are the highest authority on you. You know yourself best. You know what you need, want, and value. Stick to your guns and remain true to yourself, no matter what pressures are exerted from others.

• Don’t let anyone else make decisions for you. Healthy and sound boundaries make it possible for you to respect your own strengths, abilities, and individuality as well as those of others.

• An unhealthy imbalance occurs when you encourage neediness, or present as needy; interpersonal boundaries become tainted when you want to be rescued, or become the rescuer.

• Surround yourself with those with whom you can be fully genuine; with whom you feel comfortable to be your full and true self: treasure and invest in relationships with those who seem to unconditionally accept and support the real you.

• Identify role models who consistently maintain flexible, healthy, and balanced interpersonal boundaries.

• Spend quality time with loved ones frequently.

• Monitor, identify, and label your emotions to yourself and allowed to trusted others.

• Work on pacing the degree to which you reveal private thoughts or feelings with peers, and titrate that process, in a thoughtful, graduated manner.

You can provide teens the handout summarizing information about interpersonal boundaries.

“What About Me?”

Invite the group to share and discuss “What About Me?” examples from their own lives that relate to the topic covered in the current module. Encourage the teens to share either victories or challenges; either type of scenario can provide teachable moments.

Homework

As a homework assignment, ask the group to pay attention to their bodily signals of emotions and take note of their triggers and warning signs during the subsequent week. They should also be provided the treatment goal worksheets and directed to complete them, prior to the next session.

MaPS-Teen Module 1 Summary Outline

Materials Needed

Introductions, Check-Ins, and Icebreaker Question

• Taking turns between sessions, have one teen volunteer a “fun” or icebreaker question. Examples include the following: “What is your favorite band (animal, sport, etc.) and why?” “If you could be an animal, which animal would you be and why?”

• Encourage eye contact with peers and appropriate vocal tone and projection prior to each adolescent introducing him- or herself.

• Ask each teen to provide the following information:

Guidelines

• Brainstorm workshop guidelines with the teens. A sample list might include the following:

• Listen when others are speaking.

• Do not raise your hand while others are speaking

• Turn off all electronics, including cell phones, iPods, iPads, etc.

• Keep what others share during the workshop confidential, with the following limitations:

– Facilitators would need to break confidentiality if (i) you are hurting someone else, (ii) someone else is hurting you, or (iii) you are hurting or have plans to hurt yourself.

• Convey that it is okay to tell your parents what you did or learned in workshop but not what other teens said or did because that is their personal business.

• Refrain from developing personal relationships outside of group while in program.

Review

Treatment Goals: Individual and family

• Facilitate discussion regarding goals each youngster has for themselves and their family and what skill sets they have mastered, along with those with which they are still struggling.

• Handout syllabus to new patients and cue them to orient their treatment goals around the topics and skill sets outlined in the syllabus.

Feelings: Good, Bad, and Ugly

• Generate broad discussion of feelings.

• What are feelings? Are they important? Whose are important?

• What feelings “get them in trouble?”

• What is the purpose of feelings?

• Ask, “Are emotions good or bad?”

• Help teens realize that emotions are not “good” or “bad”, they are natural and serve important functions.

• Discuss if behavioral responses to emotions can be “good” or “bad.”

• Encourage the teens not to ignore their feelings, and remind them that emotions serve a purpose. Share that it does not make you a bad person if you have anger; it’s what you do with the feeling that counts.

• Ask the teens, “Is it ever a good thing to be angry about something?” May also provide the group with historical, contemporary, or hypothetical events or situations during which anger was put to good use. For example, a group of peers getting angry over how a bully is treating someone and deciding to tell the administrator so that it stops is a positive result of anger.

Ambivalence or Mixed Feelings

Feelings Vocabulary and Intensities

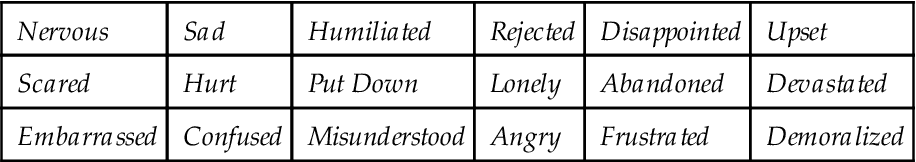

• Invite discussion and brainstorm regarding negative or uncomfortable feelings. Generate list on whiteboard such as the one that follows:

| Nervous | Sad | Humiliated | Rejected | Disappointed | Upset |

| Scared | Hurt | Put Down | Lonely | Abandoned | Devastated |

| Embarrassed | Confused | Misunderstood | Angry | Frustrated | Demoralized |

• Assist teens in distinguishing feelings from thoughts or perceptions/judgments.

• Have the group define intensity of feelings, which can be summarized as how little or how much you feel a feeling.

Feeling Identification and Somatic Monitoring

• Invite the group to reflect upon and discuss the various bodily signals and sensations they have experienced, associated with various feelings.

• Where in your body do you feel sadness (hurt, anger, etc.)?

• How do you know you are becoming sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

• How would you describe the sensation of feeling sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

• What changes do you notice in your body when you begin to feel sad (hurt, angry, etc.)?

• Choose two or three feelings as examples and generate lists on the whiteboard as the teens share examples.

• Some examples of physical sensations noted in association with various feelings include the following list:

• “I feel sick to my stomach.”

• Discuss mind–body connection and guide the group to recognize the value of attending to early bodily signals, especially for anger.

“Fight-or-Flight” Response

• Generate discussion about the “fight-or-flight” response. Discuss its origin and purpose as well as the physiological or physical changes associated with it.

• Orient group to the terms “Savage” brain (amygdala, brainstem) versus “Civilized” brain (prefrontal cortex, frontal lobes)—one all brute force, no intellect or reason—the other less powerful, but much, much more intelligent, effective, and mature!

Feeling Triggers

Interpersonal Boundaries

• Facilitate discussion around the notion of interpersonal boundaries including inviting a definition of the term.

• Interpersonal boundaries are the physical, emotional, and psychological limits we establish to demarcate ourselves from others. These lines enable us to distinguish our own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors from those around us.

• Cue the group to reflect upon the value of striking a balance between remaining separate and distinct, psychologically, from peers, versus allowing one’s definition of self and self-worth to be utterly dependent on feedback from others.

• Provide psycho-education regarding what is known in reference to optimal adolescent psychological development and social success, that is, that flexible and balanced interpersonal boundaries promote well-being and healthy relationships.

• Brainstorm with the group a list of strategies for retaining psychological autonomy, while building positive interpersonal connections with peers. Ask them to consider the following examples:

• Your significant other is pressuring you, more and more, to give up time with your family and abandon your other peer friendships.

• Your group of friends is fiercely pressuring you to style yourself in a manner that consistently conforms to their patterns of dressing, accessorizing, and wearing of hair and make-up.

• You find yourself unable to tolerate ever being alone and on an emotional roller-coaster that is dictated by the degree to which you perceive acceptance and approval from peers.

• You struggle to make decisions independently and never seem to be able to form an opinion or make a choice, on your own, without first consulting one or several peers.

• You are unable to tolerate being single, even for a few weeks and do not feel content or complete, unless in a committed, romantic relationship.

• You find yourself changing friend groups often, and each time you adopt a new style, demeanor, values, musical taste, and interests/hobbies.

• Use cut-out cards with scenarios to facilitate an exercise with the group, having members take turns selecting a card and reading it aloud.

• Cue discussion around patterns of being overly open and diffuse in relationship style, rushing in too fast, too intensely versus remaining overly walled off or closed.

• Brainstorm strategies for promoting appropriate interpersonal boundaries and consolidation of identity or sense of self. Examples include the following:

• Take responsibility for how you allow others to treat you.

• Set clear and decisive limits so that others will respect them; then be willing to do whatever it takes to enforce them.

• Recognize that other people’s needs and feelings are not more important than your own.

• Learn to say “no.” A healthy amount of self-interest is necessary for ensuring boundaries. You should not do anyone favors at your own expense.

• Identify the attitudes and behaviors that you find unacceptable. Set limits with others in advance and be prepared and willing to let others know when they’ve crossed the line, acted inappropriately, or disrespected you in any way.

• Strive to determine who constitutes your true self; remain loyal to that person; do not succumb to pressures from others to be anyone else.

• Trust and believe in yourself. You are the highest authority on you. You know yourself best. You know what you need, want, and value. Stick to your guns and remain true to yourself, no matter what pressures are exerted from others.

• Don’t let anyone else make decisions for you. Healthy and sound boundaries make it possible for you to respect your own strengths, abilities, and individuality as well as those of others.

• An unhealthy imbalance occurs when you encourage neediness, or present as needy; interpersonal boundaries become tainted when you want to be rescued, or become the rescuer.

• Surround yourself with those with whom you can be fully genuine; with whom you feel comfortable to be your full and true self: treasure and invest in relationships with those who seem to unconditionally accept and support the real you.

• Identify role models who consistently maintain flexible, healthy, and balanced interpersonal boundaries.

• Spend quality time with loved ones frequently.

• Monitor, identify, and label your emotions to yourself and allowed to trusted others.

• Work on pacing the degree to which you reveal private thoughts or feelings with peers, and titrate that process, in a thoughtful, graduated manner.

Wrap Up and Answer Questions

Handouts/Business Cards

Module 1-MaPS-Teen Teen Workbook Cover

Module 1 MaPS-Teen Teen Handout #2

Module 1 MaPS-Teen Teen Handout #3

Module 2-MaPS-Teen Sample and Blank Interpersonal Scenario Cards Therapist Tool #1

Module 1-MaPS-Teen Teen Handout #4

Module 1 MaPS-Teen Teen Handout #5

Family Strengths and Goals Interview: Teen Version

Directions: Pair with a parent from another family and alternate asking and answering questions with them, until the interviews have been completed. Write down answers as you go, and prepare to share the responses, with the group, when the interviews are done.

Teens Ask Parents (paired with adult from another family):

1. What is your favorite feature of your family?

2. Describe something your teen does really well?

3. What works really well in your family?

4. What is something you wish you could change about your family?

5. What is something you wish you could change about yourself?

6. Describe a favorite memory of a time with your family.

7. Share three activities (you think your family would be willing to do), that you would like to do with your family.

8. What would you be willing to do, to improve your family relationships or help in achieving your family goals?

MaPS-Teen Module 2

Introductions and Guidelines

Begin Module 2 of the MaPS-Teen program with an orientation if there are new members, introductions, “check-ins,” and a review of workshop guidelines, as detailed in the MaPS-Teen Orientation, Introductions, Guidelines section. Follow the same basic routine at the start of each session. After introductions and “check-ins” are completed, mention the overarching topic of the current session, and write the schedule for the day on a dry erase board, with time allocations specified for each section. If there are new teens, take a few minutes to review the program syllabus, including highlighting and briefly describing the topics or skill sets to be covered, throughout the program. For subsequent sessions, review these elements as needed for new members, including providing them with copies of the program syllabus, along with recruiting established patients to welcome and briefly orient new ones. It is ideal to provide the participants with a 5-minute break at about the halfway point of each session; juice and snacks can be provided during this time.

Icebreaker Exercise

At the start of each session, immediately after orientation for new members, but prior to introductions and check-ins, have the teens brainstorm and vote on a “fun” or icebreaker question. Have group members answer the question at the end of their introduction and check-in. This is completed to assist teens in getting to know one another and enable them to be less guarded and more comfortable.

Review

Once introductions have been made, guidelines have been reviewed, and the current session’s topic mentioned, conduct a brief review of material from the previous session for no more than 10 minutes, challenging returning teens to recall previously taught skills and information.

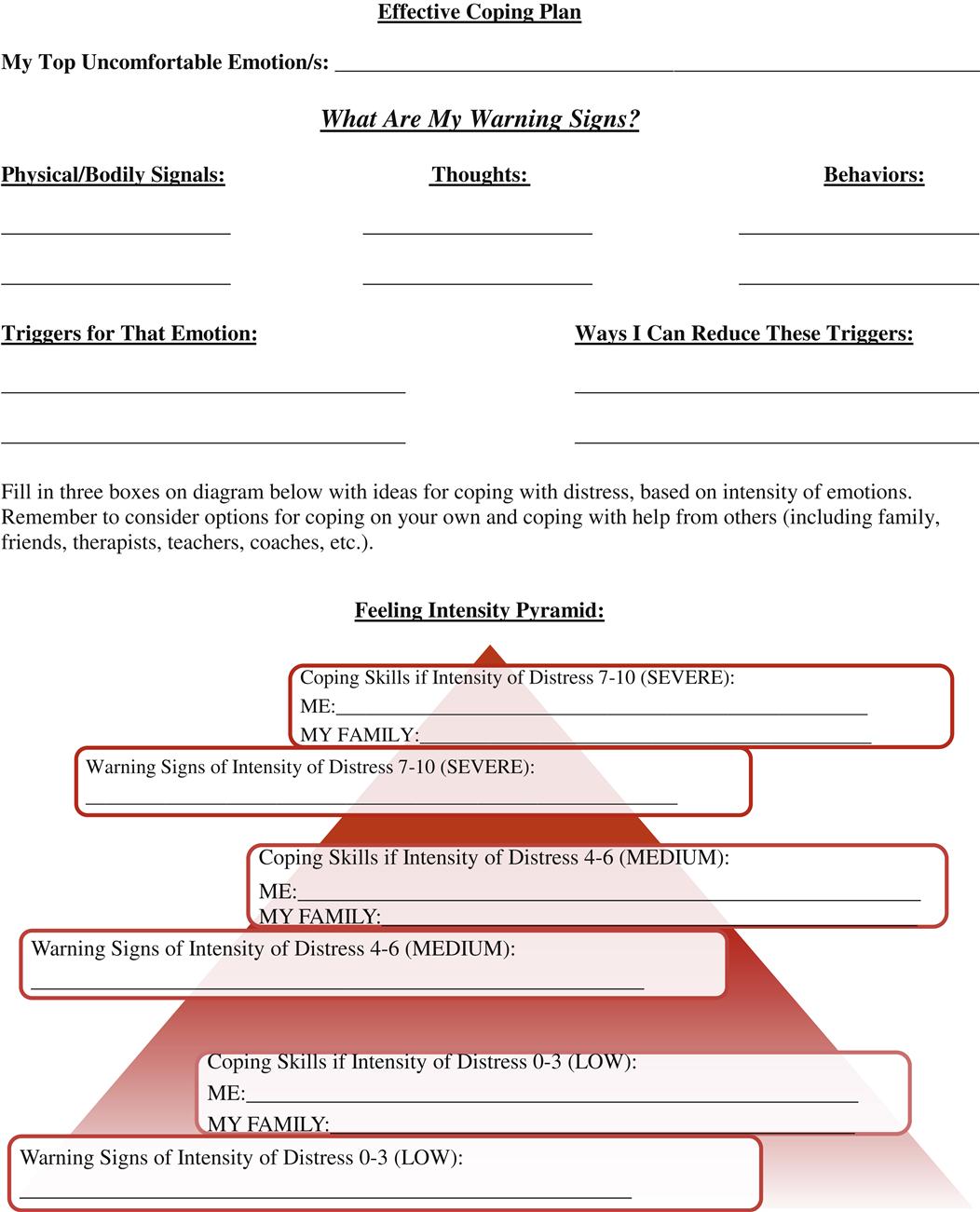

Effective Coping Skills

Reiterate to the teens the point that if they can learn to recognize their distressing or uncomfortable emotions early and identify patterns that characterize the evolution of their emotions, then they can learn to manage their reactions and behave in a manner that leaves them feeling competent and empowered. Facilitate discussion regarding potential “healthy coping skills” that are additionally effective. Clarify what is meant by “effective.” Teens often mistakenly consider a coping skill effective only when the skill completely or greatly diminishes their current uncomfortable emotion. Explain to teens that a coping skill is considered “effective” if it decreases the intensity of the uncomfortable emotion by even a small degree (e.g., decreases anger on a 10-point scale from a “10” to an “8.5”). Reiterate that individuals don’t “think well” when their emotions are very intense and any factor that can reduce the intensity of an emotion is considered effective. Further explain that if anger is at an “8.5” versus a “10,” an individual is much more likely to manage their anger effectively than if it were a “10.” Invite the group to consider whether or not the strategy they might find effective when their degree of upset is at a “3” would be likely to work well, when their distress is elevated to a “7” on a 10-point scale. Help them recognize and cue them to discuss the range of intensity emotions can have, and consider what strategies to deploy, contingent upon their degree of distress.

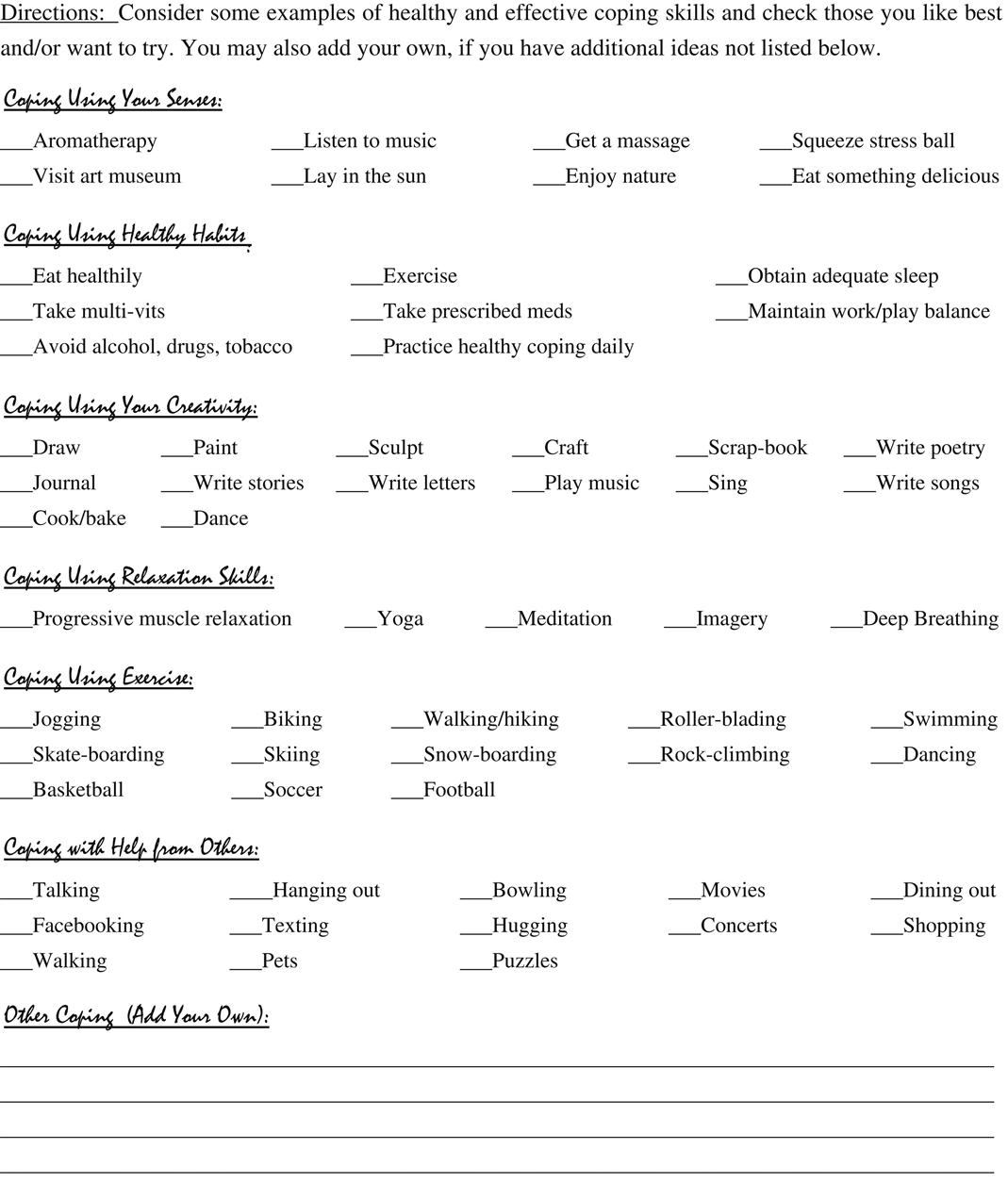

Encourage the teens to share their current most effective, preferred, healthy coping skills with the group. Go around the circle and have each teen mention a healthy and potentially effective coping skill they have tried or would like to try. Organize the discussion by listing a series of categories of coping strategies on a dry erase board and cue the group to brainstorm ideas, one category at a time. Examples of broad categories of coping skills include, “Coping Using Your Senses,” “Coping Using Your Creativity,” “Coping Using Relaxation Exercises,” “Coping with Help from Others,” and “Coping Using Healthy Habits.” The teens will typically indicate having tried an array of healthy and unhealthy, as well as effective and ineffective, coping strategies. Cue them to focus on approaches that were both healthy and effective, while jotting them down on the dry erase board, under the appropriate category heading. Examples might include journaling, listening to music, video gaming, and texting or talking to friends or family members, walking, or playing with a pet and drawing.

Go around the circle a few times and conclude the discussion by handing out a comprehensive list of coping skills to the group, available as a handout on the book’s companion website. Pause for a few minutes for the group to look over the list and check their favorite options, as well as add their own, if desired.

Encourage the group members to practice several of these skills, at home, and then rate their effectiveness (scale of 1–10) during the subsequent week. Also, encourage them to keep their list of potential coping skills handy (on their phone, in their journal, etc.), so they can reference the list, when they are having a difficult time. This practice is advised to continue, until they are very experienced in utilizing a solid set of healthy, effective coping skills. Again, remind them that when emotions are intense, it becomes significantly more difficult to think clearly and control behavioral impulses. They can use their Effective Coping Skills Worksheet to cue them and record their experiences. Explain to the teens that it is important to set aside time each day to “practice” their most effective coping skills or to try new ones. If an individual practices some form of relaxation daily, even for only 10–15 minutes, over the course of a few weeks, they can achieve something called the “generalization response” (Bournes, 2005) whereby they reset their baseline level of arousal at a lower level, hence increasingly the threshold for triggering agitation, a temper outburst, or a threat response. This habit not only serves as a preventative measure (e.g., their emotions are less likely to reach their peak intensity if they listen to relaxing music three times per day), but also increases the likelihood that they will be able and inclined to utilize the skills when they actually need them.

If teens don’t rehearse relaxation and healthy and effective coping skills, while they are “cool-headed” and experiencing low levels of arousal, they won’t master the techniques to the degree necessary, to deploy them during episodes of intense distress or heightened arousal. A useful metaphor to share is the idea of trying to teach someone to tie their shoes, when the building is on fire. To effectively tie one’s shoes, in the context of attempting to evacuate a building on fire, one must have mastered the skill to the point that no thinking is required and the person can complete the task automatically and reflexively. The primitive, survival portion of the brain is taking over, fueling physiological arousal and the skills needed in the heat of the moment must be hard-wired and second nature. The same principle is at play with being able to call up relaxation and coping skills, when in the midst of heightened arousal or intense distress. The teens must know the techniques “cold” and be adept at performing them effortlessly, as if on “auto-pilot.”

Invite the group to consider a personalized plan for coping with distress that involves proactively identifying and rehearsing effective and healthy strategies that can be applied across a range of emotions, at varied levels of intensity. Handout the worksheet titled, “Effective Coping Plan.” Provide pens or pencils and allow the teens to take a few minutes to complete the worksheet. Invite the group to then share “popcorn” style their ideas generated via the worksheet completion exercise and any plans for implementing coping strategies. The completed worksheets should be saved for home use, but also for the sake of participating in this modules’ joint session, during which families will be asked to exchange their ideas for coping plans.

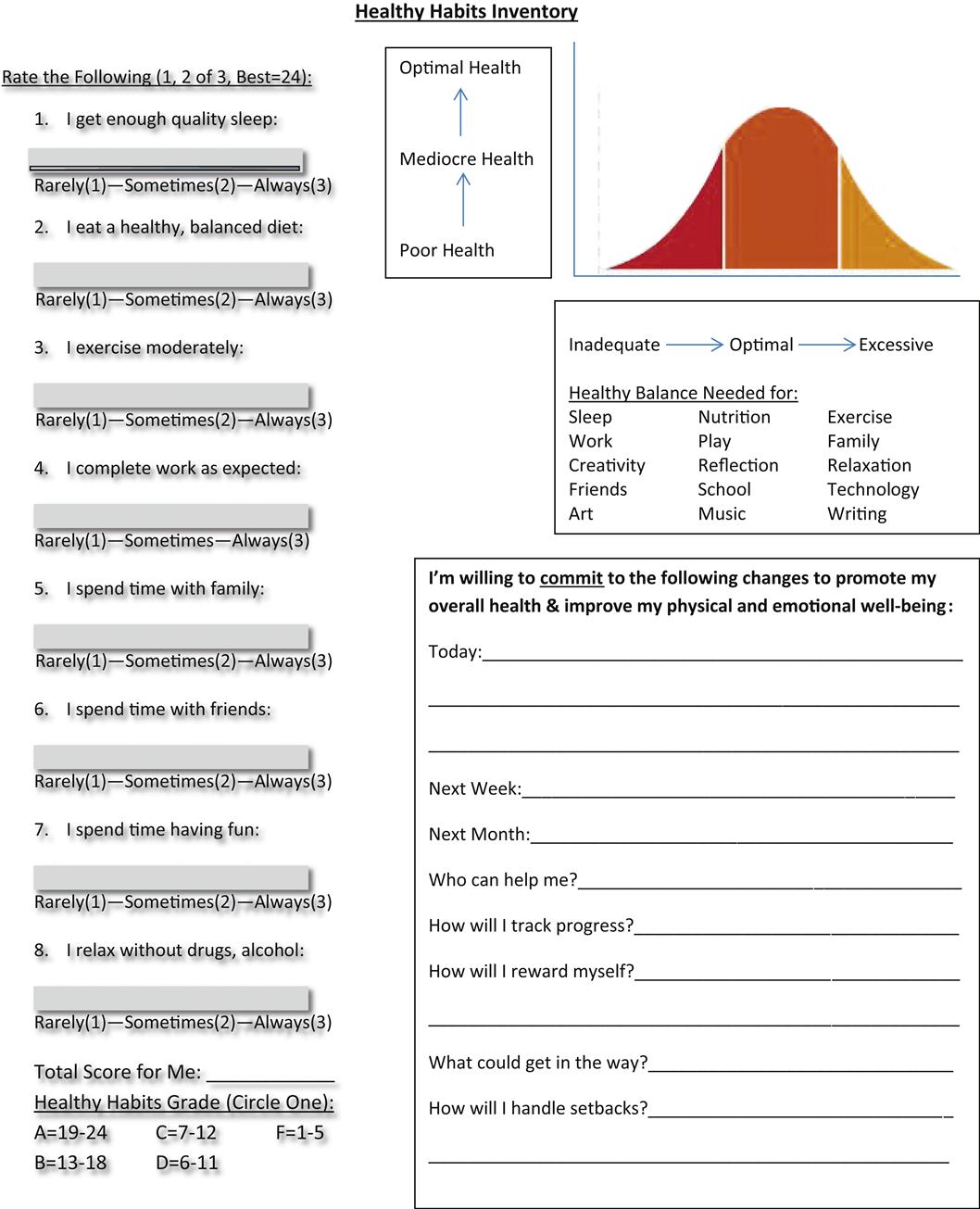

Healthy Habits

Stimulate discussion with the group by cuing them to set a goal (if they haven’t already) of modifying their overall lifestyle, as a family, such that they are very deliberate in forming habits and scheduling and engaging in recurring activities that rejuvenate them physically and emotionally. Using a method of didactic discussion, with content prompts from facilitators, guide the group to recognize that to optimize health and functioning, families must commit to living a balanced life, with a sufficient degree of energizing and restorative habits, targeting both individual and relationship health, that occur no matter what. Such health-promoting activities function akin to preventative immunizations against rare but devastating diseases such as polio or rubella.

A healthy and balanced lifestyle is made, not born, and it requires continual and painstaking maintenance through conscious and willful effort. A family and individual must prioritize health promotion to the degree that those activities and habits are pursued, routinely and consistently, despite competing agendas. Sufficient time and energy must be specifically allocated in a proactive manner to promoting and preserving overall and fundamental individual and relationship well-being. In no place does the old adage, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” ring more true than in the field of stress management.

Facilitate a discussion around the basic elements of healthy living, cuing the group to reflect upon the roles of sufficient and regular sleep, exercise, nutrition, along with socialization with family and friends and a balance between time and energy devoted to work, school, and fun. Most teens who’ve been suffering a mood or anxiety disorder have compromised sleep and nutrition. They may have lost a balance to their lives and often have neglected their health in fundamental ways, such as failing to meet basic dietary, rest, and exercise requirements.

Through guided didactic discussion, ensure the teens are made aware that inadequate sleep severely compromises all aspects of cognition, and impedes learning and memory (Louca & Short, 2014). Inadequate nutrition can slow growth, lower energy, impair focus, and even contribute to the onset and persistence of depression and other emotional problems (Gauthier et al., 2014). Daily aerobic exercise, in moderate doses, protects against eating disorders and improves sleep, energy, concentration, and mood, while relieving stress and reducing anxiety (Rosenbaum, Tiedemann, Sherrington, Curtis, & Ward, 2014).

The point should be made that healthy living is all about balance—too much or too little sleep, calories, exercise, work, play, etc. can severely compromise overall health, potentially impairing all domains of functioning—academic, social, emotional, and physical, to name a few. Conclude this section by handing out the “Healthy Habits Inventory,” and pause for a few minutes for the teens to complete this worksheet. Then pull the group’s attention back together and invite the teens to share their findings about their lifestyle habits and overall health score. Also encourage group members to reflect up and share their plans for improving their own overall health and cue teens to offer one another feedback and support around their deficit areas and ideas for self-care.

Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders

It is well established that youth with mood disorders are additionally at high risk for a multitude of psychiatric comorbidities, including anxiety, disruptive and substance use disorders (AACAP, 2007). Youngsters who are primarily depressed often experience elevated anxiety and are likely to present as irritable much of the time. In addition, youth with bipolar spectrum mood disorders struggle with affect regulation and relaxation training can provide them with tools for lowering their arousal, thereby stabilizing their mood. Adolescents with patterns of explosive aggression and disruptive behavior often benefit from training in relaxation or other deescalation strategies. Teens tend to be sincerely interested in learning ways to control their impulses and regulate their feelings—especially anger. Most of these youth are able to master some simple relaxation techniques fairly readily, and parents report observing them to use these tools at times, instead of “blowing up.” It is worthwhile to devote some time to modeling, teaching, and rehearsing some basic relaxation techniques.

Stress and Anxiety

Leading up to the provision of relaxation training, facilitate a brief discussion about “stress,” including a definition, as well as factors that increase or diminish the level of “stress,” experienced by a particular individual. Ask the group what types of experiences, situations, events, or conditions precipitate and perpetuate stress for them. Typical, everyday occurrences are often experienced as stressful to youngsters and some may be ill-equipped to manage routine stressors and therefore especially vulnerable to developing anxiety and/or mood disorders, along with impaired functioning. The teens might mention family or peer issues, personal appearance, romantic relationships, school pressures, jobs, or teachers, as potential sources of stress.

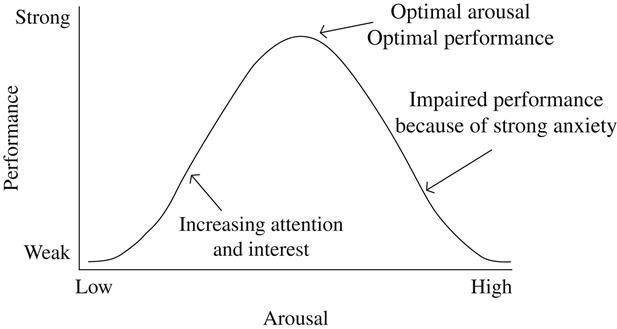

Draw the anxiety versus performance curve (Diamond, Campbell, Park, Halonen, & Zoladz, 2007), as it appears below, on the board and facilitate discussion regarding the role of stress or anxiety on functioning.

Ensure the group appreciates the “take home” point made by the curve, that is, that some anxiety is normal and healthy. Too little or too much anxiety can markedly impair performance and functioning (Diamond et al., 2007). The goal, of course, is to maintain balance and keep the stress or anxiety level in an optimal range, conducive to optimal emotional health and functioning.

Relaxation Training

Introduce some common relaxation techniques such as abdominal or “belly breathing,” progressive muscle relaxation, and visualization or imagery, to the teens. Do so by briefly providing an overview of potential techniques and then engaging the group in active rehearsal of a sample relaxation exercise. If relaxation exercises are practiced daily for at least 10–15 minutes, over time, they produce a “generalization response” (Bournes, 2005), whereby there is a gradual lowering of the individual’s baseline level of anxiety. In addition, with daily practice, teens will increasingly master various relaxation techniques and be increasingly able to manage their own anxiety and distress, using their favorite relaxation-inducing methods.

It has been well established that youth undergoing treatment for anxiety are unlikely to practice anxiety-reduction exercises independently, outside of therapy, unless they have first performed them together in session, with live therapist modeling and coaching (Kircanski & Peris, 2014). These arousal-lowering techniques are often experienced as awkward, uncomfortable, and difficult to master, by anxious and depressed youth. However, through a process of experiential learning, in which therapists demonstrate exercises together while instructing teens to follow along, many patients can begin to appreciate the value of relaxation techniques. They often at least experience mild to moderate relief of their anxiety and bodily tension through the course of performing relaxation exercises during group, which leads to increased “buy in,” and bolsters their inherent motivation to independently repeat those experiences, on their own.

Explain that by simply changing the way they breathe, the teens can relieve their own anxiety, stress, or anger. They can actually change their body’s blood chemistry or physiology, when they adjust their breathing. Breathing slowly and deeply is the most efficient way to oxygenate and induces a relaxed state. In addition, share with the adolescents that it has been shown that sequentially tensing and then releasing muscles can help one achieve a state of deep relaxation (Bournes, 2005). Visualization or imagery is a relaxation technique that most youngsters really like and respond to quite well. It allows them to use their imaginations and most youth find it fun and engaging. Imagery works because it is a form of distraction that requires intense focus, and interrupts a cycle of obsessive worrying. Furthermore, it can work by conjuring up positive and pleasant emotional memories, especially when adolescents are recruited to write their own personalized narratives to use for imagery exercises involving their individual peaceful scene.

Ask the teens to recall a fond or favorite memory of a place or event during which they felt warm, comfortable, and at peace. Nearly everyone is able to recall shining or peaceful moments in their lives during which they felt contented, serene, or joyful. For an adolescent, an example might include a memory or imagined scene of lying in warm sand, with their toes in the water, camping in the mountains, or fishing in a river or from a boat on a lake. Encourage the teens to generate as vivid a description as possible of a favorite memory that they can use for practicing imagery, with consideration for the sights, sounds, smells, and tactile sensations associated with the recollection. Have them record it on paper for later use during the group relaxation exercise demonstration to follow. The adolescents also may wish to draw their peaceful scene and place it somewhere where they go to actively relax.

A sample script, inclusive of a few, common “bread and butter” relaxation techniques, can be read aloud while therapists demonstrate and teens follow along, practicing the performance of relaxation exercises during group. A copy of the following relaxation exercise compilation script is available on the book’s companion website and can be provided to the teens to take home. The room should be prepared as much as possible, for the sake of producing an atmosphere conducive to relaxation training. Room preparatory options might include dimming the lights if possible, ensuring no interruptions to the group, and playing nature sounds or other relaxing, but not distracting, background music. The following script combines elements of deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and imagery, all of which are among the more well-established and popular relaxation techniques available.

Quiet Body, Quiet Mind

Invite the youth to position themselves comfortably either in their chairs, or on the floor, an adequate distance from their peers. Dim the lights slightly, and ensure that everyone is comfortable and has adequate personal space. Attempt to eliminate any interruptions or distractions. Model the exercises in front of the teens as they perform them concurrently.

You may read the following aloud, while you demonstrate the exercises being described: