By January and February 1945 it was time to escape—escape the Russians closing in, escape the abysmal war, escape the demands of diehard Third Reich authorities—Hitler included—that the Peenemünders remain and fight to the death. The von Braun missile team had SS orders to move south to the Harz Mountains and to await further word there.

Before heading inland, von Braun made a brief visit to the Baltic farm estate of relatives in Pomerania to say his good-byes. He had made a point to include his cousin,1 the lovely blond and blue-eyed daughter of his uncle, Alexander von Quistorp, a prominent banker, landholder, and aristocratic brother of his mother, Emmy. This would not be the last that fifteen-year-old Baroness Maria Louise von Quistorp and the almost thirty-three-year-old bachelor Baron Wernher would see of each other.

Von Braun and his advisers hatched a scheme to carry out the retreat to the Harz Mountains, they later said, with an eye toward an eventual rendezvous with American forces. On the official SS stationery which his officer’s status entitled him to use, von Braun wrote himself bogus orders to move some five thousand civilian personnel, along with mountains of scientific equipment, machinery, vital documents, and V-2 missile parts, by truck, train, and automobile. Then he had the fictitious designation VABV affixed to all the vehicles. During the dangerous exodus, whenever suspicious German guards halted the main convoy, von Braun confidently showed his “orders” and pointed to the conspicuous VABV signs. He explained that the letters stood for Vorhaben zur Besonderen Verwendung (Project for Special Dispositions). He hinted that this was a top-secret effort being carried out for none other than SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Without fail, the guards waved them through.2

They traveled only at night, to avoid Allied aircraft attacks. During a night drive at high speed and with no headlights, von Braun’s driver fell asleep. Hannes Luehrsen, a facilities master planner, was in a trailing car and later described the spectacular crash in reminiscing with von Braun: “Way back, there was a moment when I feared you would not even see your [next] birthday. . . . All of a sudden your car soared like a glider from the Autobahn against the ramparts of a below-ground railroad track.”3 In the bloody accident von Braun suffered a nasty break in his left upper arm and a facial gash whose scar he would carry for the rest of his life. His driver was killed instantly.

First stop for the missile team was Bleicherode, near Nordhausen and the underground Mittelwerk missile factory. The retreating technical corps settled into abandoned factories and other empty buildings. A thousand trucks and dozens of trains had transported the personnel and tons of missile assemblies and parts, machinery, fixtures, and documents to the interim location. Much of the V-2 hardware was hidden in caves and old mines.4

After a month’s stay in Bleicherode, new orders came in mid-March from SS Gen. Hans Kammler, whom Himmler had put in overall command of Peenemünde and of V-2 volume production at Mittelwerk. Army Major General Dornberger (who had retained certain administrative duties), von Braun, and five to six hundred of their best technical and support people were to move farther south to Oberammergau, in the northern foothills of the Bavarian Alps. They also were ordered to destroy their tons of V-2 blueprints, production drawings, and other secret documents before pulling out. Instead, Dornberger and von Braun sent trusted team members to hide the precious papers in nearby abandoned mines and to dynamite the entrances shut.

At Oberammergau the team of missile experts was housed with SS security men in barracks surrounded by barbed-wire fences. Von Braun had heard rumors that the SS high command was prepared to liquidate the rocket group rather than have it fall into enemy hands. He figured the notorious Kammler wanted the cream of the V-2 team held under guard so he could either trade them to the Allies to save his own skin or kill them before capture.5 In time, von Braun was able to convince the security officers that Germany’s missile brain trust could easily be destroyed by a single Allied bombing attack that would “wipe out the last chance for the ‘ultimate victory’”—and how would that sit with SS higher authority? As a precaution, he argued, the rocketeers should fan out among twenty-five nearby villages in the mountains.6

The SS security officers bought the idea. Soon Dornberger, von Braun, his brother Magnus, and two dozen colleagues, accompanied by their guards, relocated in early April to a resort hotel, Haus Ingeburg, in the village of Oberjoch. There they waited, for weeks. Von Braun later described the unusual nature of those days. “There I was, living royally in a ski hotel on a mountain plateau. There were the French [forces] below us to the west, and the Americans to the south. But no one, of course, suspected we were there. So nothing happened. The most momentous events were being broadcast over the radio: Hitler was dead, the war was over, an armistice was signed—and the hotel service was excellent.”7

Gradually the SS troops guarding the dispersed V-2 team members disappeared, especially after news came that Adolph Hitler died on April 30. Ernst Steinhoff persuaded the last SS holdout with his group to shed his uniform and pose as a missile engineer for his own safety.8 Clearly, if the von Braun team was intent on surrendering to the Americans, now was the time to act.

And if the German missile men were looking for the Americans, the reverse was equally true. Von Braun and his fellow scientists and engineers from Peenemünde were on an extensive list of Third Reich scientists and other technical specialists sought by the U.S. forces—and by the British, the Russians, and the French, none of whom were cooperating with one another. This was a deadly serious competition for “intellectual reparations,” a quest that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the “Wizard War.”9

With time running short in the dying days of the war in Europe, von Braun and Dornberger decided someone must venture down from their hideout and contact the U.S. troops they knew to be nearby. They chose von Braun’s brother Magnus, then age twenty-six. “I was the youngest, I spoke the best English, and I was the most expendable,” he later said.10

On May 2, 1945, the day after Hitler’s death was made public, Magnus von Braun dressed in ordinary clothes, climbed on a bicycle, and headed down the mountain road. Two miles later, near the town of Schattwald, he encountered an advance antitank patrol unit of the 44th Infantry, U.S. Army Third Armored Division. Challenged in German by Pfc. Fred P. Schneiker of Sheboygan, Wisconsin, Magnus responded in alternating German and perfect, British-accented English, “We are a group of rocket specialists up in the mountains. We want to see your commander and surrender to the Americans.” The group also wanted to be “taken to see ‘Ike’ as soon as possible,” he added.11

Schneiker escorted the young German straight to CIC (Counter-Intelligence Corps) headquarters in the small Austrian town of Reutte. The officer in charge, unaware of the high-priority quest for the V-2 team, told Magnus to come back the next morning with the leaders of his group. At dawn the next day a fleet of cars carrying the von Braun brothers and other key missile men started down the mountain to Reutte.

What did von Braun expect? Did he fear arrest and punishment? As he told an interviewer a few years later: “Why, no. We wouldn’t have treated your atomic scientists as war criminals, and I didn’t expect to be treated as one. No, I wasn’t afraid. It all made sense. The V-2 was something we had and you didn’t have. Naturally, you wanted to know all about it. When we reached the CIC, I wasn’t kicked in the teeth or anything. They immediately fried us some eggs!”12

Preliminary interrogation by army intelligence officers began at Reutte. At first his questioners could hardly believe that this jolly young scientist—his shoulder and broken left arm encased in an elaborate plaster cast, his body grown pudgy from weeks of inactivity and tasty hotel food—was the main brain of Hitler’s vaunted missile program. As Bill O’Hallaren, the division’s public relations sergeant on the scene, remembered, “He seemed too young, too fat, too jovial” to have been in charge of the V-2 as claimed.13

Von Braun mixed amiably with American soldiers, posing for snapshots, telling them about his achievements in rocketry and dreams of space flight. One GI quipped that the U.S. Army had captured “either the biggest scientist in the Third Reich or the biggest liar!”14 It did not take the army long to resolve that question. Soon all of the more than four hundred von Braun team members taken into custody at Reutte were moved to military barracks at Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Bavaria, where interrogation proceeded in earnest. Questioning by CIC technical intelligence teams composed of such first-rate U.S. scientists as General Electric’s Richard W. Porter and the California Institute of Technology’s Fritz Zwicky, an astrophysicist, and rocket scientist Clark Millikan removed all doubt that the Americans had landed the real thing.

Zwicky later recalled that von Braun shared his advanced thinking on future multistage rockets for not only Earth satellites but also large orbiting space platforms and manned flights to the Moon and planets. Von Braun found the interrogators’ grilling “extremely intelligent,” and he recognized them as “top scientists.”15

The U.S. intelligence teams had each of the rocket experts write a detailed autobiography. With this and independent information, investigators began verifying their credentials, checking out their backgrounds, probing for early Nazi or other unsavory political leanings, looking for any tendencies toward violence, and seeking clues to their true characters from teachers, former neighbors, and others, recalled Maj. Gen. John G. Zierdt, U.S. Army (Ret.).16

The missile men waited it out, uncertain of their fate. One of them, Johann J. “Hans” Klein, an expert in both guidance-control and propulsion systems, years later reminded von Braun of those days:

The dark weeks of early 1945 after our move from Peenemünde began to brighten when you outlined your ideas and concepts of satellites and probes. I remember we occupied ourselves in Garmisch-Partenkirchen by making performance and trajectory calculations under the most primitive conditions. When we needed technical estimates on such strange items as life support provisions, you steered us in the right direction with the same confidence and far-sighted outlook you showed during the V-2 and Wasserfall development.17

Within the overall American hunt for German talent, a sharp-witted West Pointer, Holger N. “Ludy” Toftoy, had the mission of seizing V-2 missiles and ferreting out and interrogating the weapon’s creative corps.18 Colonel Toftoy, chief of the Army Ordnance Corps’ Rocket Branch in Washington, became the head of Army Ordnance Technical Intelligence in Europe, based in Paris. He was directing efforts to locate and liberate enough V-2 partial assemblies and components for shipment of one hundred missiles to the United States when welcome word came of the surrender of von Braun and his core group to the U.S. Army. While ordering full interrogation of the rocketeers, Toftoy and staff were frantically spiriting the missile parts and equipment out of what would within days become the Russian and British zones of occupied Germany. They narrowly succeeded, using trains to haul the booty to Antwerp. There, it filled sixteen Liberty cargo ships bound for New Orleans. The army team also raced the clock to recover the hidden tons of missile documents that von Braun’s group had sealed in the caves ahead of the Russians—and again succeeded.19

Commented one U.S. official: “One of the greatest scientific and technical treasures in history is now securely in American hands.”20 The U.S. seizure of the von Braun team reportedly infuriated Stalin. “This is absolutely intolerable,” the Soviet chief is reported to have fumed. “We defeated the Nazi armies; we occupied Berlin and Peenemünde; but the Americans got the rocket engineers!”21

“After my field intelligence teams started to interrogate the German scientists,” Toftoy recalled after the war, “I soon felt the information on missiles was so great and so important that it should not be handled by routine field reports.”22 He decided that a sizable number of von Braun’s associates must be brought to the United States, at least for a time, for even more extensive brain-picking—and possible temporary employment. But how many? And who? Von Braun was asked to draw up a limited list of those he thought should go.

“The first list he submitted was for five hundred—including our secretaries and everybody!” recalled Maxe Neubert. “That did not go over too well with the Army.”23 Von Braun, however, had convinced at least one of his primary interrogators, GE’s Dick Porter, that the United States should import five to six hundred of his team members for optimum benefit. Porter made that recommendation to Toftoy.24

Decades later Porter shared his first impressions and memories of his encounter with the V-2 team’s technical chief in May 1945 in Garmisch.

Well, we were all pretty suspicious of each other. . . . Von Braun was reserved, but he didn’t refuse to answer [questions]. . . . I always liked him and got along well with him. And what I liked most was that he knew his business. Everything he said to me made sense.

First of all, we had to know where and who [his] people were. I was amazed at von Braun’s ability to tell me exactly what such-and-such a man could do, what his strengths and weaknesses were, and so on. He knew his people individually. He knew at least six hundred people well enough to tell you what they could do. My greatest admiration for the guy was this ability.25

Porter took a leading role in tracking down many of the prime Peenemünders who had scattered throughout Germany as the fighting waned and exploring with them the idea of coming to the United States. Aerodynamics expert Rudolf Hermann and his group, found in need of food and medicine, were gathered up along with their wind tunnel and whisked out of the future Soviet sector just in time. Missile guidance specialist Wilhelm Angele, whom von Braun had put on the “wanted persons” list, as Angele later proudly joked, was found working as a farmhand near Hannover in order to eat.26

Meanwhile, Toftoy knew Washington would never approve bringing as many as five hundred German rocket experts to America. The colonel whittled the recommended number down to three hundred and in June 1945 sent a cable to the army chief of ordnance at the Pentagon. Sent under the authority of the Allied Supreme Commander in Europe, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the cable stated that the army had in custody more than four hundred of the top V-2 research and development personnel. The “thinking” of their technical leaders was twenty-five years ahead of U.S. work in rocketry, the cable also stated. It urged their immediate evacuation to the United States.27

Toftoy later explained why he had thought the team should be imported as intact as possible. “A lot of these men had spent their entire adult professional career in rockets, and others who were brought in were highly specialized and renowned throughout Germany in other fields of science. The team was the most complete and competent that I had ever run into, and they had years of experience in working up to that particular point. So I felt they should come as a team—not as individuals.”28

Toftoy believed that “this specialized group would do the country a lot of good,” saving years of rocket research and development effort, along with many millions in taxpayers’ dollars.29 Some in the U.S. military in those pre-Hiroshima months also believed that these Germans and their V-2s might be useful in defeating Japan.

After hearing no word for weeks on his request, Toftoy flew to Washington “to personally plead the case,” he recalled years later. In late June 1945, the army and the Departments of War, State, and Commerce finally approved his recommendation, provided that only a “limited” number of Germans came over. The army brass in Washington set the figure at one hundred, no more. Toftoy then returned to Germany “to negotiate the trip and handpick those to come.”30

He met in August with von Braun and his top team members in an abandoned schoolhouse in the small town of Witzenhausen, where many of the mostly young missile men and their families had found temporary quarters. “The first thing Toftoy did,” von Braun recalled, “when he met with us and saw the situation of the families, most of whom had come to Witzenhausen as refugees from all parts of Germany, was to order a generous supply of milk for the youngsters and the babies.”31 Von Braun and his team never forgot the American colonel’s compassion.32

The group began paring down the list of hundreds of V-2 team members to just one hundred who would continue their work in the United States under short-term contracts. They pored over individual files, evaluated capabilities, and weighed all the factors. As tentative selections were made, more background investigations and further security screening took place. As each final selection was made, a paperclip was placed on that chosen man’s file. Thus, the project came to be known as Operation Paperclip, or Project Paperclip.33

Try as they might, Toftoy and von Braun could not trim the list to an even one hundred. The operative figure became 118, which was eventually expanded to 127. “I am really sorry, but mathematics has always been my weak spot,” a chuckling Toftoy said years afterward. “I often had difficulties adding and subtracting plain numbers.”34

No one ever challenged Toftoy over the higher number. In the end, a handful of the 127 backed out, deciding to remain in defeated, devastated, divided Germany for personal, family, or career reasons.35 Such turndowns, though few, may have prompted the notion that von Braun and Toftoy had trouble persuading enough of the rocket men to leave Germany for the recently hated United States and an uncertain future. “Some people have the idea that we were forced to go to America,” one of the chosen, Maxe Neubert, said later. “That’s not true. Von Braun could easily have got one thousand to go.”36

“I saw a new life,” recalled Walter Wiesman, youngest of those selected. “There was nothing left for us in Germany.”37 Still, just picking up and going was not easy for some. “It was difficult to leave our families and our homeland,” Konrad Dannenberg remembered, “and we didn’t know if the Americans would milk us dry of our knowledge and send us back as the Soviets did later with the German rocket people they got.”38

The Soviet Union did indeed round up its own group of V-2 engineers, scientists, and technicians at war’s end—some five thousand in all (as well as abandoned trainloads of von Braun’s missile equipment that was awaiting shipment southward). A few had chosen to throw in their lot with the Russians, but most were ferreted out within the Soviet zone in Germany and elsewhere, hauled off against their will to the USSR, and put to work near Moscow.39 “I do think the United States got the best of our group,” von Braun later said, hardly surprisingly. “The Americans looked for brains, the Russians for hands.”40

Part of the U.S. deal with the von Braun rocket experts involved setting up a temporary camp for their dependents. Most dependents had at least some money, but it was of little value in the immediate postwar period when food, medicine, and other necessities were scarce at any price.

The dependents were housed in former military barracks at Landshut in Bavaria. It was to be their home while the missile men were in America—or until Washington decided what to do next with these former enemies. The men’s salaries would pay for their dependents’ upkeep at Landshut.

Some dependents were still trapped in Russian-controlled areas and had to be brought to Landshut “by cloak-and-dagger methods,” among them Baron Magnus and Baroness Emmy von Braun. When the Yalta agreement gave Silesia to Poland, the elder von Brauns lost their lands and home. One account had them making their way to Berlin “on a rusty cattle train,” with the help of one of Toftoy’s key staff officers, Maj. James P. “Jim” Hamill, U.S. Army, and eventually to refuge in Bavaria. Receiving word their parents had safely reached Landshut, the grateful von Braun brothers wrote to thank Hamill.41

Across the Channel, British authorities and scientists understandably wanted to talk with the mastermind behind the V-2. In August 1945, an uneasy von Braun was flown to London along with several other German rocket experts and kept at a military camp near Wimbledon. Von Braun was picked up daily by a military intelligence officer and driven to government offices in London for questioning.

The man whose lethal rockets had rained down on England expected a chilly reception. “I must admit that I thought the British might be unfriendly to me, but I found I was wrong the first day I spent at the Ministry. I was interviewed there by Sir Alwyn Douglas Crow, the man in charge of developing British rockets. I was hardly inside his office before we were engaged in friendly shoptalk. He was curious about the headaches we’d had at Peenemünde, and he gave me a good picture of the damage the V-2 had done in England.”42

Von Braun also had a chance to see some of the V-2 damage during his daily drives to and from the London interview site. One day his military driver halted the car in front of the ruins of what had been perhaps a six-story building struck only months earlier by one of the missiles. Several minutes passed in silence as von Braun viewed the destruction out the window. Then the car moved on.43 After a fortnight’s stay in England, von Braun was returned to U.S. Army hands in Germany. There had been no charges of war crimes, no public trial.

Major General Dornberger did not fare so well. Von Braun, who did not hesitate to credit him for “the better part of my success in life,” had hoped his commander at Peenemünde would gain a ticket to America along with the civilian members of the team.44 But no deal. U.S. authorities acquiesced to British demands that Dornberger be handed over. He was interrogated by the British and then tried on charges of war crimes. Although he was acquitted, he spent two years in jail during the legal process before being released.45

U.S. authorities cooperated with London in another postwar request. The British sought to assemble and test launch several V-2s. More than one hundred former Peenemünders—without von Braun—joined British rocket engineers temporarily at a site near Cuxhaven. The project was named Operation Backfire. Three V-2s were launched out over the North Sea, all successfully, and then the Germans were returned home.

The main body of German “paperclip” rocketeers was to leave for America in early November, aboard ships under official army orders that concluded: “Upon completion of this duty the civilians named below will be returned to this [European] theater.” After all, how long could it take to pick these guys’ brains, anyway, before shipping them home? Von Braun knew differently, and so did Toftoy.

An advance group—von Braun, Eberhard Rees, Maxe Neubert, and four other select members of the missile team—were chosen to travel to the United States several weeks ahead of the main body. On September 12, 1945, the seven climbed aboard a covered army truck at Frankfurt and headed with their jeep escort toward Paris. Neubert years later cited another example of von Braun’s “golden and never-ceasing optimism, which you were able to transplant into your friends and [in] this way [create] your devoted team”:

Riding sideways in the back of a three-quarter-ton Army truck from Frankfurt to Paris, and while crossing the River Saar, the border between Germany and France, you said, “Fellows, take a good hard look at your country, which we are just leaving. It might be many years before you will be seeing Germany again.”

All we had at the time of this border crossing was a six-months contract with the United States Army and their option for a six-months extension.46

In mid-September the advance group was flown from Paris to Boston. The men were taken to Fort Strong in Boston harbor for more questioning and fine-tuning of plans for the next steps. There, von Braun met Major Hamill, the rescuer of his parents. A tall, German-speaking ordnance officer in his twenties, who had graduated from Fordham University with a degree in physics, Hamill would be the rocketeers’ military overseer for the next several years.

He later shared his thoughts on meeting the V-2 team’s leader for the first time. “My first impression of von Braun was that here was a very forthright man. He was perfectly willing to talk on any subject, and I saw a look of wonderment on his face at times as he perceived what the New World held. Though he was ill when we met . . . he still reflected great strength, both physically and mentally.”47

Hamill and von Braun traveled to Washington and the Pentagon, where they talked with Ordnance Corps top brass for five days. The rest of the advance party was taken to the army’s Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland to begin tackling the monumental task of sorting through the tons of seized V-2 documents shipped from Germany.

The rest of the 118 German rocket men came over in three separate shiploads to Boston between November 1945 and February 1946. Most then headed for their new, perhaps quite temporary home, the army’s Fort Bliss, near El Paso, Texas, on the border with Mexico.

Few beyond the Pentagon and President Harry S Truman knew that these German rocket scientists were even in the United States. That fact was still a secret kept from the rest of the nation in late September 1945, when von Braun traveled incognito from Washington, D.C., to Fort Bliss by regular train, escorted by Major Hamill. The first part of their trip was fairly uneventful, but in St. Louis Hamill noticed that their tickets for the balance of the ride to El Paso had them in sleeper car “O,” not a numbered car as was usual. Hamill inquired about it. “Oh, you’ll enjoy that trip, Major,” replied the St. Louis stationmaster. “We have nothing on that train but wounded veterans of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions.” With great effort Hamill managed to get himself and von Braun switched to a regular passenger train.48

During the trip to El Paso, Hamill, who was in uniform, avoided staying constantly at von Braun’s side so as not to arouse suspicion. One time when they were separated, a friendly Texan sat next to von Braun, introduced himself, and asked von Braun where he was from.

“Switzerland,” was the accented reply.

“Oh, yes,” the Texan said. “I’ve traveled all over Switzerland. What’s your business?”

“Uh, the steel business,” von Braun improvised.

“Why, that’s mine, too!” the other man exclaimed. “What’s your product?”

“Ball bearings,” the German said, confident he was safe now. He was not. The Texan, it turned out, was an expert on the subject!

Fortunately for von Braun, his talkative new acquaintance had to leave the train then at the Texarkana stop. Departing, the Texan pumped von Braun’s hand, slapped him on the back, and blurted out, “If it hadn’t been for you Swiss, I doubt if we could have beaten those Germans!”49 It was a story von Braun took great delight in retelling.

One of his strongest first impressions of the United States was the swarms of automobiles he saw, especially in the larger cities. Another early impression: the vast landscapes sweeping past his window during the long train ride to west Texas. An “overwhelmed” von Braun would later say “it still startles me” to be able to travel for days in America “without crossing borders or being subject to passport or custom control, such as you constantly encounter in Europe.”50

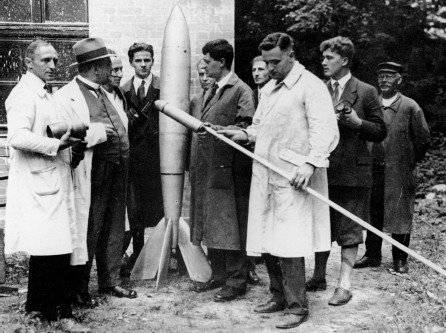

In 1930, an eighteen-year-old Wernher von Braun (in knickers) serves as a volunteer apprentice to a group of rocket experimenters in Berlin headed by Hermann Oberth. From left are: Rudolf Nebel, Alexander Ritter, Hans Bermüller, Kurt Heinisch, Oberth, two unidentified men behind Oberth, Klaus Riedel, von Braun, and an unidentified mechanic.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

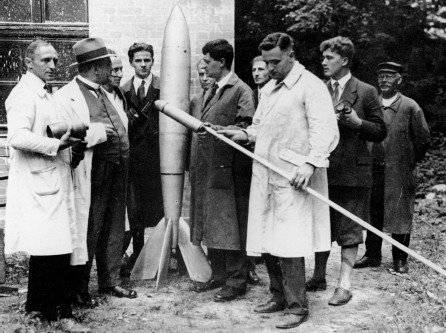

Rudolf Nebel, at left, and von Braun, age eighteen, carry their group’s experimental Mirak rockets to launch sites for test flights at Raketenflugplatz, Berlin-Reinickendorf.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

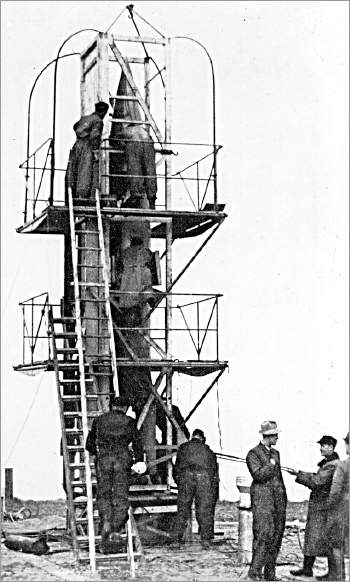

Von Braun’s Kummersdorf group readies an A-3 experimental rocket for a wintry test flight in the mid-1930s at its launch site beside the North Sea. This was before the German army rocket team’s move—beginning in 1937—to the large, new Peenemünde center on the Baltic Sea.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

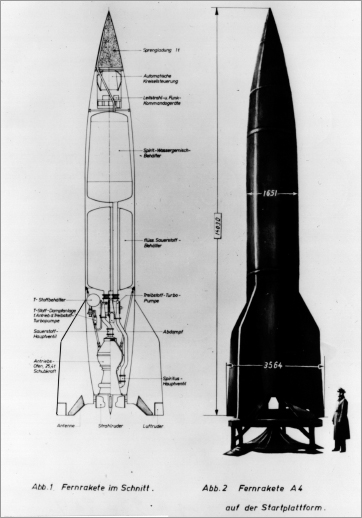

German A-4 (V-2) missile documents confiscated in 1945 by the U.S. Army show, at left, an engineering cutaway view and, right, the forty-six-foot-tall rocket on der Startplattform (launch pad), with flame deflector plate below.

David L. Christensen

Adolf Hitler, third from right, visits the Kummersdorf rocket development station outside Berlin on March 23, 1939, von Braun’s twenty-seventh birthday. At the German army facility, Hitler witnessed static engine test firings and was briefed by von Braun and Col. Walter Dornberger. Primary rocket development activities had shifted two years earlier to the much larger Peenemünde center, which Hitler never visited.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

Gen. Erich Fellgiebel, head of the German army’s Information Services, congratulates members of the Peenemünde team for the first successful launch of an A-4 (V-2) rocket on October 3, 1942. Von Braun looks on from rear center. From left are: Lt. Gen. Richard John of the Ordnance Department; Col. Walter Dornberger, commander of army rocket work at Peenemünde; von Braun; Gen. Leo Zanssen, accepting congratulations as base commander; Captain Stoelzel of the Taifun antiaircraft rocket project; Rudolf Hermann, chief of supersonic wind tunnel operations at Peenemünde; and Gerhard Reisig, chief of field test instrumentation.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

In-development A-4 (V-2) ballistic missile is test fired from Launchpad 7 at the Peenemünde rocket center around 1943.

The Huntsville Times

Von Braun and Walter Dornberger, center, host a 1943 visit to Peenemünde by Gen. Walter von Axthelm, second from left, chief of German antiaircraft weapons, for discussions of surface-to-air missile development.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

With an A-4 (V-2) missile in the background, von Braun (at right in dark suit) accompanies a contingent of top brass during a May 1943 visit to Peenemünde. In front of von Braun, Gen. Walter Dornberger turns to speak to one of the officers. At center in dark naval greatcoat is Grand-Admiral Karl Dönitz. At far left is von Braun’s propulsion chief, Walter Thiel (killed three months later in the first RAF bombing).

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

The August 17, 1943, Royal Air Force bombing raid on Peenemünde killed 735 people, wounded hundreds more, and inflicted extensive damage. Most of the visible A-4 (V-2) propellant tanks and nose cones in storage, however, survived the surprise British attack.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

A row of finished V-2 propellant tanks in a Peenemünde plant in 1944 illustrates that limited V-2 production continued after the massive August 1943 RAF raid. Tidy housekeeping and strict safety rules prevailed there; overhead, for example, is a Rauchen verboten (No Smoking) sign.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

Nazi flags adorn the façade of the officers club at Peenemünde. The SS took control of the rocket development center away from the German army and the Luftwaffe after the devastating RAF attack in August 1943.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center