The achievement by 1969 of Project Apollo’s objectives of depositing earthlings on the Moon and returning them safely home presented an occasion for much reflection. For the people of northern Alabama, this was a time to contemplate not only that momentous event but also to reflect on the profound changes wrought in that lower Appalachian locale during the two decades since the rocket people had come, and even since the decade of Apollo had begun.

Socially, demographically, culturally, economically—the community of Huntsville had been transformed from a small cotton town to a relatively progressive, racially desegregated, urbanized, high-tech mecca. Residents could trace the metropolitan makeover directly to the arrival and continued presence of Wernher von Braun & Company.

The 1950 influx of the Germans from Fort Bliss, Texas, to Redstone Arsenal had found a city still struggling to recover from a post–World War II bust. Huntsville then had maintained its position as the largest cotton market east of Memphis; surrounding it was a fertile sweep of cotton country that was ranked the most productive in the state. But as older townspeople also remembered twenty years later, a quarter of the city’s population back then had fewer than five years of formal schooling; less than a fifth had finished high school; and college graduates were almost as scarce as hen’s teeth.1

By 1950 the community’s historic high of a dozen textile mills had dwindled to just three. Its once-thriving wartime ordnance and chemical arsenals, where employment had soared from zero to more than fourteen thousand workers at their peak, were back near zero again.

With the advent of Project Apollo just eleven years after the arrival of von Braun and his rocketeers, however, the town’s roller-coaster economy had turned skyward once again. The Tennessee River Valley town at the top of Alabama had literally boomed: Thunderous static-firing tests out at “the base” made cash registers jingle in the city’s new shopping centers. The cotton town now embraced nicknames like “Rocket City, USA” and, its favorite exercise in hyperbole, “Space Capital of the Universe.”

As the lunar triumphs of the 1960s neared an end, two decades of state- and community-oriented actions and influences by von Braun also drew to a close. All across Huntsville and Redstone, now the home of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, was an array of buildings, institutions, and other entities whose existence, or growth, bore the space leader’s imprint.

Because von Braun took “such an intense personal interest” in it, as army missile official John L. McDaniel put it, the Redstone Scientific Information Center grew into the world’s largest library for rocketry, missiles, astronautics, and related sciences, and the U.S. Army’s largest technical library of any sort.2

The von Brauns and several German-born colleagues were instrumental in forming the Huntsville Symphony Orchestra. More than a dozen of the original rocket team members, spouses, and offspring played in the orchestra. A laboratory director, Werner Kuers, who was also a gifted violinist, was its first concertmaster. Eberhard Rees, von Braun’s top deputy, served on the orchestra’s first board of trustees. Wernher and Maria often attended the orchestra’s Saturday night classical concerts and the shorter series of pops concerts. (In 2005, the Huntsville Symphony Orchestra would mark its fiftieth anniversary. It had long since become a well-regarded all-professional orchestra, drawing big-name guest artists Beverly Sills, Yitzhak Perlman, Kathleen Battle, Van Cliburn, Yo-Yo Ma, and others.)

Longtime residents remembered that on weekends in the 1950s von Braun had physically helped build the Rocket City Astronomical Observatory and Planetarium. The mountaintop facility had opened with the second-most-powerful telescope in the southeast, and was later renamed for von Braun.

By the close of the 1960s, von Braun had taken a hand in one significant initiative after another in the Huntsville area. They ranged from promoting peaceful desegregation to lobbying for slum clearance, from pushing for equal job opportunities to attracting new aerospace industries, from encouraging economic diversity to aggressively criticizing Alabama’s Jim Crow practices and narrow-minded politicians.

Redstone by 1969 was home to multiple army missile-related agencies, other defense organizations, and several major on-base rocket propulsion R&D contractors—all in addition to NASA’s Marshall Center. All could trace their ancestry directly to the coming of the band of German and American missile experts two decades earlier. It had become arguably the world’s preeminent rocket development center—civil and military.

The four-square-mile town of 1950 had become a sprawling Huntsville of more than one hundred square miles by 1969. The number of its residents mushroomed from 15,000 to almost 135,000. It was a southern “Silicon Hollow” in the making, with expanses of computer hardware, systems software, and other technology-based industries, an education-rich populace, and the busiest public library system in the state. Modern Huntsville had become a city of brainpower—the city that Wernher von Braun made possible. One remembers the epitaph of Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723), the great English architect-designer of St. Paul’s Cathedral and many other major structures in London. It is carved at his simple burial place within the cathedral: “If you seek a monument, look about you.”3

Von Braun somehow had made time to pursue high-priority community interests through two busy decades. The city’s business leadership in 1958 had named him as the first recipient of the annual Distinguished Service Award. He was just getting started. In the early 1960s, he and a committee of associates joined forces with city leaders to enhance graduate education in science and technology at the struggling UAH (University of Alabama in Huntsville). Several of the rocket experts—German and American born—taught there for years as adjunct professors in their off-hours.

The city’s aerospace organizations had found it difficult to attract and retain enough bright young engineers and scientists because the community had no university where they could advance their capabilities and careers by working on master’s degrees and doctorates. Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical College (later university), high on a hill just outside the city, was a historically black state institution in that era of de jure racial segregation in the South. It did not offer the necessary technical courses and advanced-degree programs, and its leadership showed little interest in moving in those directions. The same held true for the community’s private Oakwood College, a four-year, largely liberal arts, international Seventh-Day Adventist institution for blacks. Both institutions’ position on the matter beneficially changed in a few years’ time.

After the 1960 start of construction of a permanent UAH campus, and hard on the heels of President John F. Kennedy’s lunar challenge, von Braun had spoken in June 1961 to a joint session of the Alabama Legislature. He explained Huntsville’s need for advanced-degree programs and asked for approval of a $3-million bond issue for a UAH-based research center. He noted that space was already big business in Alabama and stressed how this action would benefit the entire state.

“Let’s be honest with ourselves,” he had told the legislators. “It’s not water, or real estate, or labor, or cheap taxes that brings industry to a state or city. It’s brainpower.” It was the educational triangle of Boston University, Harvard, and MIT, “not beans,” that had brought the great electronics boom to the Boston area. “For a $3-million investment now, I promise you that you’ll reap billions, easily billions.”

Before the speech, von Braun and his assistants had been anxious about the reception he would find at the state Capitol. “This was just sixteen years after the big war was over, and there were some members of the legislature who had fought in Germany and may not have had a great deal of fondness for him,” remembered Foster A. Haley, a senior MSFC public affairs officer.4

Using slides, humor, and the basic speech Haley had written for him, von Braun turned on his charm. He received a standing ovation. “He went down there,” Haley recalled, “and he just wowed them.” The legislature passed the measure unanimously. In the Alabama statehouse, it was tough to get unanimous consent on Mother’s Day proclamations, let alone a piece of funding legislation. The state’s voters later that year approved the bond issue by a wide margin. A year or so after that, Haley was with von Braun as they drove past the construction site. “Don’t you wish you had asked for $10 million?” Haley asked. “You’d have gotten it.” Von Braun could only agree on both counts.5

The $3-million University of Alabama Research Institute opened in 1962, strengthening the university’s graduate teaching and research programs. The institute’s first director was Rudolf Hermann, von Braun’s chief aerodynamicist from the Peenemünde days. UAH became a rarity among universities in having master’s and doctoral programs in several technical disciplines before it offered undergraduate degrees in those fields. By 1969–70, UAH had matured from a fledgling 1950 extension center of the mother campus at Tuscaloosa to a flourishing, five-thousand-student, autonomous campus that offered advanced degrees in science and technology as well as the humanities. The impact of von Braun and his native-German-led rocket team on the college prompted one of the enrolled students to propose in fun that UAH’s name be changed to “the University of Bavaria.” After all, reasoned the student, “If it had not been for the Germans, there would be no college here.”6

In 1963 von Braun did an encore performance before the Alabama Legislature. This time he asked the lawmakers for almost $2 million to create the Alabama Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville as an educational facility, visitor attraction, and showcase for the space program and army missile R&D activities. “When von Braun spoke, you could have heard a pin drop,” then-State Representative Harry Pennington of Huntsville and Madison County recalled. “Everyone was hanging on his every word. . . . The bond issue was approved without a single dissenting vote. We should have asked for $20 million!”7 Voters ratified the measure by more than three to one.

The resultant “space museum,” as it was called, would open in 1970 on acreage the army sliced off Redstone Arsenal, with Pentagon and congressional approval. Von Braun helped obtain many of the needed aerospace artifacts. He finessed acquisition of the star exhibit for Rocket Park—a leftover full-size Saturn V.8 He arranged an official “transportation test” of the segmented super-rocket via flatbed carriers from the Marshall Center to the site. And there it simply stayed, reclining its full length of more than a football field. (The busy, renamed U.S. Space & Rocket Center, which houses the Wernher von Braun Library and Archives among its many other facilities, would continue to draw some four hundred thousand paying visitors a year into the twenty-first century.)

Von Braun was also behind the original Space Camp. He was strolling through Rocket Park with Executive Director Edward O. Buckbee of the Huntsville aerospace visitor center and museum and noticed a teacher with a group of children taking notes on what they were learning. A lightbulb came on. “You know,” von Braun mused, “we have all these camps for youngsters in this country—band camps and cheerleader camps and football camps. Why don’t we have a science camp? It would give boys and girls a more involved experience with science, technology, and the principles of rocketry and space flight.”9 U.S. Space Camp would materialize in 1982. The series of weeklong camps was an instant smash hit.10

Also in the 1960s, von Braun let such major space contractors as Lockheed, Boeing, IBM, Douglas Aircraft, McDonnell, and Rocketdyne know that it would be to their advantage to locate branches of their engineering operations in Huntsville. Most took the hint. This step put the big companies close to their customer and the purse of billions. This allowed face-to-face dealings between von Braun’s people and their Project Apollo contractors without blowing the Marshall Center’s travel budget on constant trips to the West Coast and elsewhere.

Von Braun had done what he could to help local aerospace companies too. One was Brown Engineering, headed by former cotton trader Milton K. Cummings. Brown’s wealthy CEO was a master at building friendly relationships with von Braun and key members of his team—and at making sure his friends in Congress and Democratic administrations helped the Marshall Center at budget time. At a meeting of MSFC officials one day, the agenda included awarding a modest $1.5 million contract for a piece of work any one of the center’s technical contractors could handle.

“Von Braun brought this up,” recalled Haley. “He said, ‘Look, as long as we’ve got this work here and anybody can do it, let’s keep the money locally.’” In what several associates said reflected von Braun’s philosophy of “take care of the little guy,” he noted that Cummings needed contracts for Brown, “‘so let’s give this million and a half to him,’” remembered Haley. Almost everybody at the table nodded their heads in agreement.

But Marshall’s deputy [director] for administration spoke up and said, “Well, wouldn’t it be easier if we tack this on to a contract we already have with North American?” And von Braun said: “Yes, but most of our money goes to California. Let’s keep what we can locally.” Then he went through the whole rigmarole again and everybody nodded, “Let’s do it.” But then a guy from contracting spoke up: “Well, I don’t know. It’s just too much trouble to set up a separate contract for a million-and-a-half dollars.” Von Braun went through the whole thing again and got everybody to nod their heads, yeah, yeah, yeah [for awarding it to Brown].

At last, remembered Haley, an out-of-patience von Braun settled the matter: “Well, goddammit, let’s do it!” And that was that.11

Heeding a cue from von Braun, Cummings and his Brown Engineering president, Joseph C. Moquin, had taken the first steps in 1961 to create a research park on vacant land bordering the new UA-Huntsville campus. The company bought 150 acres, in part for a new plant complex for itself and the rest for resale at cost to other contractors. The ever-expanding site became the location favored by most of the big aerospace companies von Braun gently persuaded to build facilities in the Rocket City, and by local industries he and army missile agencies at Redstone helped sustain with contracts. (By 2005, Cummings Research Park would rank as the second largest such development in the nation and fourth largest in the world; it now sprawls over more than five thousand acres, its scores of plants, labs, and offices employing in excess of twenty thousand people.)

Also in the mid-1960s, von Braun had joined the civil rights fray in Alabama and the South. The rocket scientist spoke out in support of school desegregation, voter rights, and equal employment opportunity. Much of the motivation clearly stemmed from NASA headquarters’ wishes and the need to improve Alabama’s poor race-relations reputation, so that the Marshall Center and its contractors in the state could attract and keep top technical and management talent.

Von Braun had supported the campaign to abolish Alabama’s literacy tests and poll taxes, which discouraged many blacks, along with poor whites, from becoming voters. “All these regulatory barriers form a Berlin Wall around the ballot box,” he declared. “They discourage the qualified as well as the unqualified from registering to vote. It’s a little ridiculous to give a literacy test to a person with a college degree. Our schools aren’t that bad!”12 Years later, Fred S. Schultz of General Electric’s Space Division reminded von Braun, “Your brave address at the Huntsville Chamber of Commerce annual meeting in . . . 1964 gave the Association of Huntsville Area Companies [Contractors] the backing it needed to launch a successful drive for equal opportunity for all our citizens.”13

In another speech during the civil rights movement, von Braun had taken a swipe at feisty Alabama Governor George C. Wallace and other white-supremacist officials’ defiant attitudes toward federal authority. The space leader jabbed, “In the vernacular, it is okay to disagree, but I wonder if we have to be so disagreeable?”14

Segregation, racial discrimination, denial of civil rights—all were wrongs that von Braun had both spoken out against and taken action to stop in Alabama in the 1960s, “way before there was anything like an Equal Employment Opportunity Office,” recalled Guy B. Jackson, a von Braun speechwriter, MSFC public affairs specialist, and Baptist lay leader. Von Braun pressed for hiring more blacks and other minorities at the Marshall Center and at contractors’ plants in the area, Jackson said. He added: “Dr. von Braun was genuinely concerned about minorities. He tried to find jobs for them, and when [a minority] quit the program or dropped out without explanation, von Braun would find out and want to know why, what had happened.”15

Was the former “Nazi rocket scientist’s” outspokenness and proactive steps against segregation motivated solely by marching orders from his NASA boss and by von Braun’s self-interest as the Marshall Center’s director, as commonly assumed? The record shows that he took certain antisegregation steps before NASA chief Jim Webb’s directives came down from Washington. But how did von Braun, the man, feel toward apartheid, southern style? Did he act on moral grounds as well? James Shepherd, the facilities manager at MSFC in those days, recalled that von Braun “was quite concerned about segregation, and he was pretty outspoken.” Shepherd remembered a private moment when von Braun shared his thoughts on his special relationship to the subject of racial injustice.

Harry Gorman [MSFC deputy director for administration] and von Braun and myself were in Washington, and we had an hour or so to kill. . . . We were in a lounge talking. It was during the height of the civil rights unrest. Harry was concerned that von Braun was going to have a [KKK] cross burned in his yard. He was cautioned against that. It was a serious thing . . . and there were the problems with his different nationality and background.

Nevertheless, von Braun said that when he landed here [in America] people asked him, “Where were you? What did you do [during] the persecutions? What did you do when people were disappearing?” He said to us, “That’s not going to happen again. ... I am not going to sit quiet on a major issue like segregation.”

And he didn’t shut up. . . . You sensed he felt like “the heck with the crosses burning,” that it wouldn’t bother him. I tell you this from the standpoint of his sensitivity [to the issue].... He had been through a lot, and he knew what silence meant and the deep depression when they were aware of something [going on] and never spoke up.16

In the mid-1960s von Braun had figured in an entirely different contribution to his adopted country, remembered Randy Clinton, the defense intelligence official based at Redstone. As the Vietnam War escalated, the U.S. military prepared to bomb Hanoi and needed someone on the scene to provide information on “the functions of certain facilities and the reaction” there to the raids, Clinton recalled. A Japanese businessman who traveled to North Vietnam and knew his way around Hanoi agreed reluctantly to fill that role, on one condition. An admirer of Wernher von Braun, he said he would do it for the rocket scientist’s autograph dedicated to him, aside from other compensation.

U.S. military intelligence agents speculated that the man believed he had set an impossible condition and might thus safely dodge the covert assignment. Officials turned to Clinton’s foreign missile intelligence arm at Redstone just down the street from MSFC where von Braun worked. Clinton paid a call on his friend and explained the situation. He left with one Wernher von Braun autograph and inscription. He later learned that in due time the recruited Japanese businessman produced the desired intelligence reports.17

In the end, for all von Braun had done for his adopted hometown, state, and the nation he had chosen to serve, the community at large did everything but canonize him.

The Project Paperclip rocket team at Fort Bliss, Texas, around 1946. Wernher von Braun is in the front row, seventh from right, in dark pants and light jacket.

U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command

Charles Lindbergh, second from right, visits von Braun, second from left, and colleagues at White Sands Proving Ground, New Mexico, about 1946–47, to check out the latest in ballistic missile technology. The two were together again a quarter century later for the Apollo 11 liftoff in July 1969.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

In the late 1940s, a launch crew of Americans and Germans prepares a V-2 for a test flight from White Sands Proving Ground (later Missile Range) in New Mexico.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

In an early 1950s moment at home, von Braun divides his time between his daughter, Iris, and a copy of a new book he had just coauthored, Conquest of Space.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

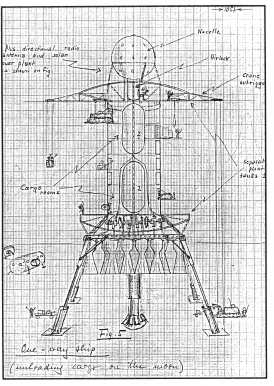

Von Braun’s drawing of a lunar cargo ship described in his article “The Journey,” part of Collier’s October 18, 1952, special issue titled Man on the Moon.

Fredrick I. Ordway III Collection

Walt Disney, second from right, joins von Braun and colleagues in July 1954 during work on a series of educational television programs about space at Disney Studios in Burbank, California. From left are: von Braun, Willy Ley, Disney, and Heinz Haber of the U.S. Air Force Department of Space Medicine.

Bonnie Holmes

Some forty German rocket team members plus their families—including Wernher and Maria von Braun—swear allegiance to the United States in citizenship ceremonies on April 14, 1955, in the packed auditorium of Huntsville High School. (The future Mrs. Bob Ward was among the students present.)

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

Boating on the Tennessee River with their children and friends was a weekend activity the von Brauns enjoyed through most of their twenty-year stay in nearby Huntsville. Here, in a 1955 outing, Wernher and Maria, at left with daughters Iris and Margrit, relax with Irmgard and Ernst Stuhlinger (holding his son Tillman), at center and colleague Heinz Koelle at far right.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

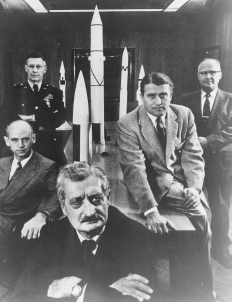

Early von Braun mentor Hermann Oberth, center foreground, poses with the U.S. Army missile hierarchy of the mid-1950s at Redstone Arsenal. Counterclockwise from Oberth are: von Braun, Robert Lusser, Brig. Gen. Holger N. Toftoy, and Ernst Stuhlinger. This photo appeared in “U.S. Races for a Supermissile” in Life magazine’s February 27, 1956, issue.

U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command

A Redstone missile is fielded by troops in Europe in 1957. Developing the 200-mile, nuclear-capable ballistic weapon was the first of two big jobs assigned to U.S. Army missile R & D operations at Redstone Arsenal, where von Braun was technical director. The second was to develop the 1,500-mile Jupiter IRBM.

The Huntsville Times

Von Braun thanks his copilot after a May 12, 1959, flight in which he piloted the U.S. Air Force F-100 jet fighter faster than the speed of sound at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Fanatical pilot von Braun was inducted into the Mach-Busters Club for breaking the sound barrier.

Bonnie Holmes

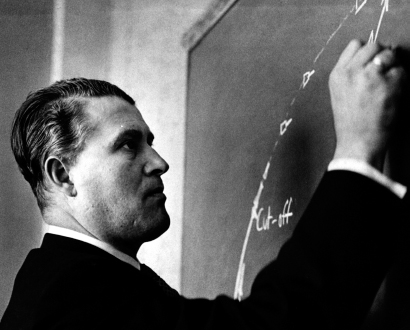

Von Braun in 1959 outlines the trajectory of the proposed suborbital Redstone-Mercury space flights of Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom.

Bonnie Holmes

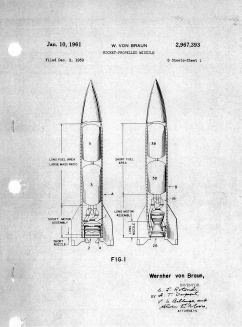

Von Braun was granted a patent in 1961 for this innovation in a “rocket-propelled missile” It improved “the mass fraction of the rocket by increasing propellant volume through shortening the propulsion system” explained another German-born rocket scientist. Exterior dimensions remained the same by lengthening the propellant tank and shortening the engine and nozzle.

David L. Christensen

Von Braun explains Saturn heavy-lift rockets to President Dwight Eisenhower during his September 8, 1960, visit to formally open the new NASA George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

The Huntsville Times

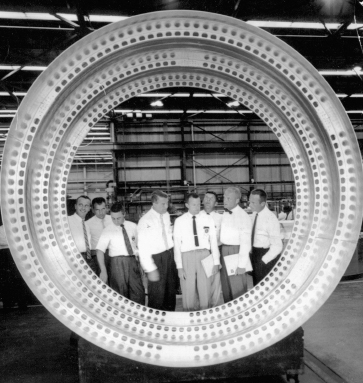

Von Braun, fourth from left, leads the original group of seven Mercury astronauts on a tour of Redstone Arsenal in 1960. The group inspects the bulkheads of a Redstone rocket of the type that would lift future admiral Alan Shepard, at far left, and Gus Grissom, third from left, on brief suborbital space flights the next year.

The Huntsville Times

Seemingly nonchalant pad workers inspect a fueled Redstone-Mercury vehicle in the predawn hours at Cape Canaveral before the morning launch of Alan Shepard. The first U.S. astronaut rocketed away on May 5, 1961, nestled in the single-seat Mercury space “capsule” atop the modified Redstone missile developed by the von Braun team for the U.S. Army.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

Von Braun does here what he did often, and effectively—testify before Congress. In this circa-1961 appearance, he briefs a space-related committee on Capitol Hill with Robert Seamans Jr., NASA associate administrator; at right.

History Office, Marshall Space Flight Center

With von Braun as host and escort, President John F. Kennedy gestures during his second visit and tour, in May 1963, of the Marshall Space Flight Center. Robert Seamans Jr. is at left.

Bonnie Holmes

Von Braun points to an image of the Saturn I rocket on a large monitor in the Launch Control Center during a 1965 flight from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center.

The Huntsville Times

With wife, Maria, von Braun sports a “five-gallon” hat given him by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the mid-1960s at the LBJ Ranch in Texas. At right is West German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard, wearing his own rancher’s hat from LBJ.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

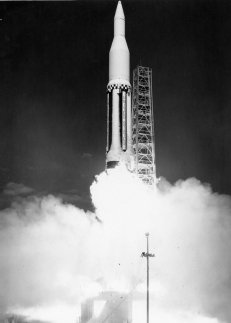

A Saturn IB booster rocket lifts off from Cape Canaveral in a mid-1960s test flight. Developed by the von Braun team and its contractor partners in industry, the Saturn IB was a step in the development of the Saturn V super-rocket that launched Apollo astronauts to the Moon from 1969 to 1972.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

Von Braun helps a young boy get a good look at a space-theme exhibit in this undated file photo. A promoter of education, Dr. Space was delighted that so many young people were interested in space exploration.

History Office, Marshall Space Flight Center

Edward C. Uhl, Fairchild Industries chief executive, talks with von Braun during a visit he made to the company in Germantown, Maryland, in 1968. Four years later von Braun left NASA and joined Fairchild as vice president for engineering and development.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

Von Braun has fun floating weightlessly inside the KC-135 “Vomit Comet” during a zero-G flight maneuver in 1968. Von Braun and his chief scientist, Ernst Stuhlinger, experienced several twenty-second weightless periods on the parabolic flights. In one or more, he wore a spacesuit to enhance the simulation of space flight.

History Office, Marshall Space Flight Center

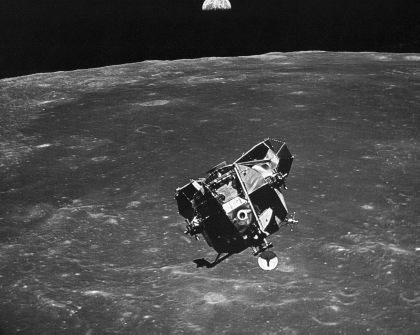

Apollo 11 lunar lander—with astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin Jr. aboard—separates in lunar orbit from the command module, where astronaut Michael Collins is at the controls—and descends for the first landing on the Moon.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

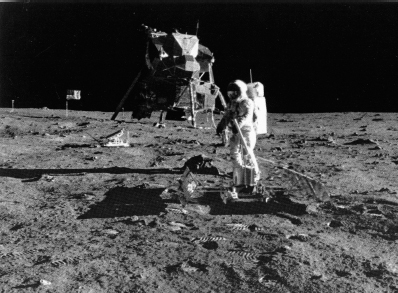

Apollo 11 lunarnaut Buzz Aldrin positions scientific equipment on the Moon’s surface during the first manned landing mission to Earth’s natural satellite.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

Von Braun experiences another sort of liftoff—an impromptu hero’s ride on the shoulders of local public officials in downtown Huntsville at the community’s Apollo 11 “splashdown celebration” on July 24, 1969.

Huntsville–Madison County Public Library

Saturn-Apollo 17, the final manned lunar-landing flight in the series, lifts off on December 7, 1972, in a nighttime launch from Kennedy Space Center. Astronaut and navy man Gene Cernan, the commander, became the last man to walk on the Moon.

U.S. Space & Rocket Center

A simple gravestone with the citation of his favorite verse of Scripture marks von Braun’s burial place in the private Ivy Hill Cemetery in a churchyard in Alexandria, Virginia.

The Huntsville Times