When, an hour after midnight, Wolfe finally called it a day and let them go, it looked as if I would be seeing a lot of the girls. Not that they had balked at answering questions. We had at least four thousand facts, an average of a thousand an hour, but if anyone had offered me a dime for the lot it would have been a deal. We were full of information to the gills, but not a glimmer of Baird Archer or fiction writing or anything pertaining thereto. Wolfe had even sunk so low as to ask where and how they had spent the evening of February second and the afternoon of February twenty-sixth, though the cops had of course covered that and double-checked it.

Especially we knew enough about Leonard Dykes to write his biography, either straight or in novel form. Having started in as office boy, by industry, application, loyalty, and a satisfactory amount of intelligence, he had worked up to office manager and confidential clerk. He was not married. He had smoked a pipe, and had once got pickled on two glasses of punch at an office party, proving that he was not a drinker. He had had no known interest in anything outside his work except baseball in summer and professional hockey games in winter. And so forth and so on. None of the five had any notion about who had killed him or why.

They kept getting into squabbles about anything and everything. For instance, when Wolfe was asking about Dykes’s reaction to the disbarment of O’Malley, and was told by Corrigan that Dykes had written him a letter of resignation, Wolfe wanted to know when. Sometime in the summer, Corrigan said, he didn’t remember exactly, probably in July. Wolfe asked what the letter had said.

“I forget how he put it,” Corrigan replied, “but he was just being scrupulous. He said he had heard that there was talk among the staff that he was responsible for O’Malley’s trouble, that it was baseless, but that we might feel it would be harmful to the firm for him to continue. He also said that it was under O’Malley as senior that he had been made office manager, and that the new regime might want to make a change, and that therefore he was offering his resignation.”

Wolfe grunted. “Was it accepted?”

“Certainly not. I called him in and told him that we were completely satisfied with him, and that he should ignore the office gossip.”

“I’d like to see his letter. You have it?”

“I suppose it was filed—” Corrigan stopped. “No, it wasn’t. I sent it to Con O’Malley. He may have it.”

“I returned it to you,” O’Malley asserted.

“If you did I don’t remember it.”

“He must have it,” Phelps declared, “because when you showed it to me—no, that was another letter. When you showed me Dykes’s resignation you said you were going to send it to Con.”

“He did,” O’Malley said. “And I returned it—wait a minute, I’m wrong. I returned it to Fred, in person. I stopped in at the office, and Jim wasn’t there, and I gave it to Fred.”

Briggs was blinking at him. “That,” he said stiffly, “is absolutely false. Emmett showed me that letter.” He blinked around. “I resent it, but I’m not surprised. We all know that Con is irresponsible and a liar.”

“Goddam it, Fred,” Phelps objected, “why should he lie about a thing like that? He didn’t say he showed it to you, he said he gave it to you.”

“It’s a lie! It’s absolutely false!”

“I don’t believe,” Wolfe interposed, “that the issue merits such heat. I would like to see not only that letter but also anything else that Dykes wrote—letters, memoranda, reports—or copies of them. I want to know how he used words. I would like that letter to be included if it is available. I don’t need a stack of material—half a dozen items will do. May I have them?”

They said he might.

When they had gone I stretched, yawned, and inquired, “Do we discuss it now or wait till morning?”

“What the devil is there to discuss?” Wolfe shoved his chair back and arose. “Go to bed.” He marched out to his elevator.

Next day, Friday, I had either bum luck or a double brush-off, I wasn’t sure which. Phoning Sue Dondero to propose some kind of joint enterprise, I was told that she was leaving town that afternoon for the weekend and wouldn’t return until late Sunday evening. Phoning Eleanor Gruber as the best alternative, I was told that she was already booked. I looked over the list, trying to be objective about it, and settled on Blanche Duke. When I got her I must admit she didn’t sound enthusiastic, but probably she never did at the switchboard. She couldn’t make it Friday but signed up for Saturday at seven.

We were getting reports by phone from Saul and Fred and Orrie, and Friday a little before six Saul came in person. The only reason I wouldn’t vote for Saul Panzer for President of the United States is that he would never dress the part. How he goes around New York, almost anywhere, in that faded brown cap and old brown suit, without attracting attention as not belonging, I will never understand. Wolfe has never given him an assignment that he didn’t fill better than anyone else could except me, and my argument is why not elect him President, buy him a suit and hat, and see what happens?

He sat on the edge of one of the yellow chairs and asked, “Anything fresh?”

“No,” I told him. “As you know, it is usually impossible to tell just when a case will end, but this time it’s a cinch. When our client’s last buck is spent we’ll quit.”

“As bad as that? Is Mr. Wolfe concentrating?”

“You mean is he working or loafing? He’s loafing. He has started asking people where they were at three-fifteen Monday afternoon, February twenty-sixth. That’s a hell of a way for a genius to perform.”

Wolfe entered, greeted Saul, and got behind his desk. Saul reported. Wolfe wanted full details as usual, and got them: the names of the judge, jury foreman, and others, the nature of the case that O’Malley had been losing, including the names of the litigants, and so forth. The information had gone to the court by mail in an unsigned typewritten letter, and had been detailed enough for them to go for the juror after a few hours’ checkup. Efforts to trace the informing letter had failed. After an extended session with city employees, the juror had admitted getting three thousand dollars in cash from O’Malley, and more than half of it had been recovered. Louis Kustin had been defense attorney at the trials of both the juror and O’Malley, and by brilliant performances had got hung juries in both cases. Saul had spent a day trying to get the archives for a look at the unsigned typewritten informing letter, but had failed.

The bribed juror was a shoe salesman named Anderson. Saul had had two sessions with him and his wife. The wife’s position stood on four legs: one, she had not written the letter; two, she had not known that her husband had taken a bribe; three, if she had known he had taken a bribe she certainly wouldn’t have told on him; and four, she didn’t know how to typewrite. Apparently her husband believed her. That didn’t prove anything, since the talent of some husbands for believing their wives is unbounded, but when Saul too voted for her that was enough for Wolfe and me. Saul can smell a liar through a concrete wall. He offered to bring the Andersons in for Wolfe to judge for himself, but Wolfe said no. Saul was told to join Fred and Orrie in the check of Dykes’s friends and acquaintances outside the office.

Saturday morning a large envelope arrived by messenger. Inside was a note from Emmett Phelps, the six-foot scholar who was indifferent to murder, typed on the firm’s letterhead:

Dear Mr. Wolfe:

I am sending herewith, as you requested, some material written by Leonard Dykes.

Included is his letter of resignation dated July 19, 1950, which you said you would like to see. Evidently Mr. O’Malley’s statement that he had returned the letter to Mr. Briggs was correct, since it was here in our files. Mr. O’Malley was in the office yesterday and I told him the letter had been found.

Kindly return the material when you have finished with it.

Sincerely,

EMMETT PHELPS

Dykes’s letter of resignation was a full page, single spaced, but all it said was what Corrigan had told us—that on account of the staff gossip that he had informed on O’Malley and so damaged the firm’s reputation, and, further, because the new regime might want to make a change, he respectfully submitted his resignation. He had used three times as many words as he needed. As for the rest of the material—memoranda, reports, and copies of letters—it may have shown Wolfe how Dykes used words, but aside from that it was as irrelevant as last year’s box score. Wolfe waded through it, passing each item to me as he finished, and I read every word, not wanting to leave an opening for another remark about my powers of observation like the time I had muffed the name of Baird Archer. When I had finished I handed the lot back to him, with some casual comment, and got at my typewriter to do some letters he had dictated.

I was banging away when he suddenly demanded, “What does this stand for?”

I got up to go and look. In his hand was Dykes’s letter of resignation. He slid it across to me. “That notation in pencil in the corner. What is it?”

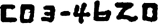

I looked at it, a pencil scribble like this:

I nodded. “Yeah, I noticed it. Search me. Public School 146, Third Grade?”

“So it is. Am I supposed to pop it out?”

“No. It’s probably frivolous, but its oddity stirs curiosity. Does it suggest anything to you?”

I pursed my lips to look thoughtful. “Not offhand. Does it to you?”

He reached for it and frowned at it. “It invites speculation. With a capital P and a small S, it is presumably not initials. I know of only one word or name in the language for which ‘P’s is commonly used as an abbreviation. The figures following the ‘Ps’ increase the likelihood. Still no suggestion?”

“Well, ‘Ps’ stands for postscript, and the figures—”

“No. Get the Bible.”

I crossed to the bookshelves, got it, and returned.

“Turn to Psalm One-forty-six and read the third verse.”

I admit I had to use the index. Having done so, I turned the pages, found it, and gave it a glance.

“I’ll be damned,” I muttered.

“Read it!” Wolfe bellowed.

I read aloud. “‘Put not your trust in princes, nor in the son of man, in whom there is no help.’”

“Ah,” Wolfe said, and sighed clear to his middle.

“Okay,” I conceded. “‘Put Not Your Trust’ was the title of Baird Archer’s novel. At last you’ve got a man on base, but by a fluke. I hereby enter it for the record in coincidences that the item you specially requested had that notation on it and you spotted it. If that’s how—”

“Pfui,” Wolfe snorted. “There was nothing coincidental about it, and any lummox could have interpreted that notation.”

“I’m a superlummox.”

“No.” He was so pleased he felt magnanimous. “You got it for us. You got those women here and scared them. You scared them so badly that one or more of them felt it necessary to concede a connection between Baird Archer and someone in that office.”

“One of whom? The women?”

“I think not. I prefer a man, and it was the men I asked for material written by Dykes. You scared a man or men. I want to know which one or ones. You have an engagement for this evening?”

“Yes. With a blond switchboard operator. Three shades of blond on one head.”

“Very well. Find out who made that notation on Dykes’s letter in that square distinctive hand. I hope to heaven it wasn’t Dykes himself.” Wolfe frowned and shook his head. “I must correct myself. All I expect you to learn is whose hand that notation resembles. It would be better not to show the letter and the notation itself.”

“Sure. Make it as tough as you can.”

But it wasn’t as tough as it sounded because the handwriting was so easy to imitate. During the afternoon I practiced it plenty before I prepared my bait. When I left for my date at 6:40 I had with me, in the breast pocket of my newest lightweight blue suit, one of the items that had been sent us—a typewritten memorandum from Leonard Dykes—with a penciled notation in the margin made by me: