Sometimes you just need to get to the heart of the matter.

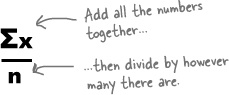

It’s likely that you’ve been asked to work out averages before. One way to find the average of a bunch of numbers is to add all the numbers together, and then divide by how many numbers there are.

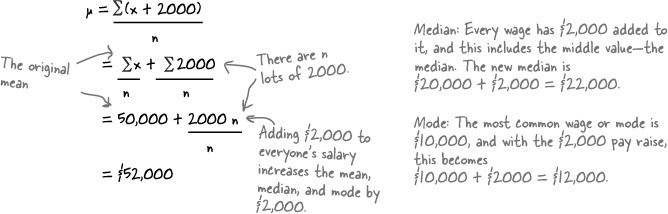

In statistics, this is called the mean.

Because there’s more than one sort of average.

We’ll be looking at other types of averages, besides the mean, later in this chapter.

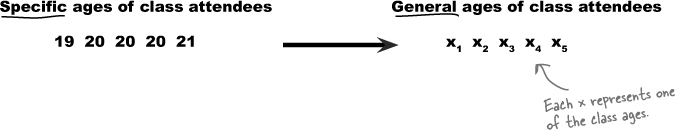

If you want to really excel with statistics, you’ll need to become comfortable with some common stats notation. It may look a little strange at first, but you’ll soon get used to it.

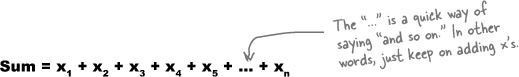

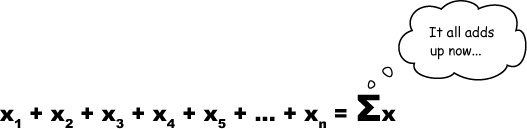

Statisticians use letters to represent unknown numbers. But what if we don’t know how many numbers we might have to add together? Not a problem—we’ll just call the number of values n. If we didn’t know how many people were in the Power Workout class, we’d just say that there were n of them, and write the sum of all the ages as:

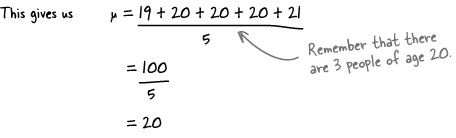

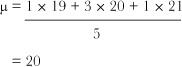

Now that we know some handy math shortcuts, let’s see how we can apply this to the mean.

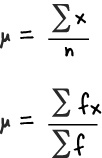

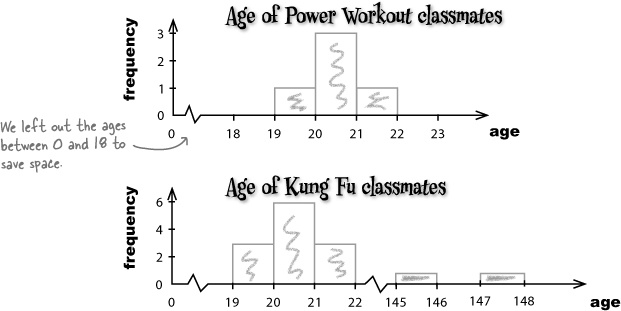

Sketch the histograms for the Kung Fu and Power Workout classes. (If you need a refresher on histograms, flip back to Chapter 1.) How do the shapes of the distributions compare? Why was Clive sent to the wrong class?

Power Workout Classmate Ages

Age | 19 | 20 | 21 |

Frequency | 1 | 3 | 1 |

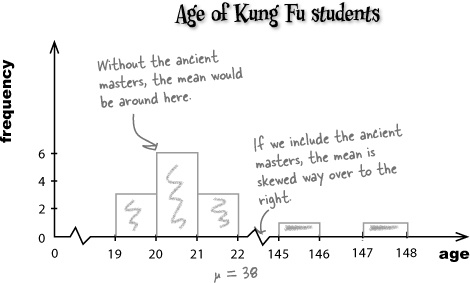

Kung Fu Classmate Ages

Age | 19 | 20 | 21 | 145 | 147 |

Frequency | 3 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

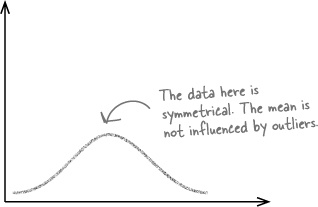

Did you see the difference in the shape of the charts for the Power Workout and Kung Fu classes? The ages of the Power Workout class form a smooth, symmetrical shape. It’s easy to see what a typical age is for people in the class.

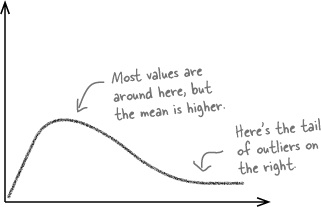

If you look at the data and chart of the Kung Fu class, it’s easy to see that most of the people in the class are around 20 years old. In fact, this would be the mean if the ancient masters weren’t in the class.

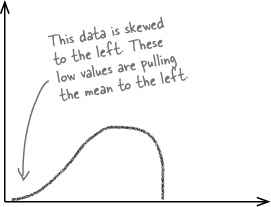

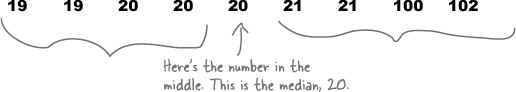

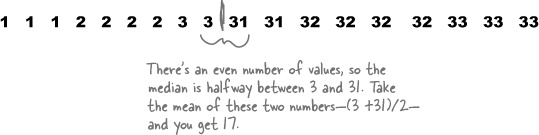

If the mean becomes misleading because of skewed data and outliers, then we need some other way of saying what a typical value is. We can do this by, quite literally, taking the middle value. This is a different sort of average, and it’s called the median.

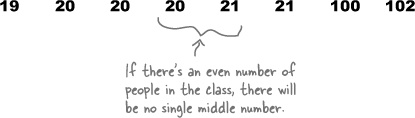

What if there had been an even number of people in the class?

Your work on averages is really paying off. More and more people are turning up for classes at the Health Club, and the staff is finding it much easier to find classes to suit the customers.

This teenager is after a swimming class where he can make new friends his own age.

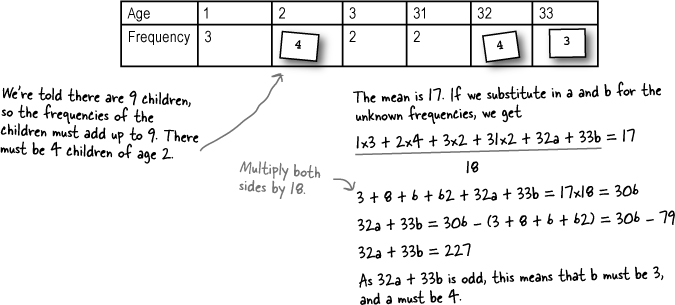

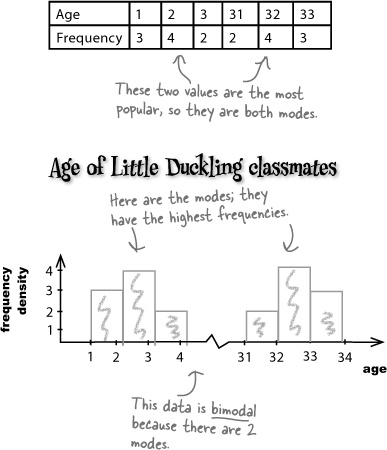

Age | 1 | 2 | 3 | 31 | 32 | 33 |

Frequency | 3 | 2 | 2 |

Here are the ages of people who go to the Little Ducklings class, but some of the frequencies have fallen off. Your task is to put them in the right slot in the frequency table. Nine children and their parents go to the class, and the mean and median are both 17.

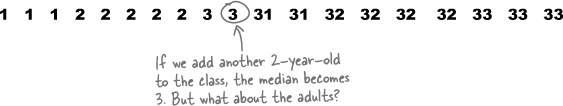

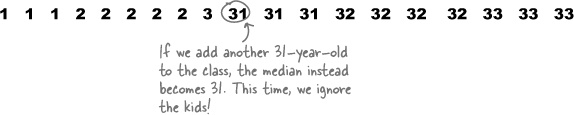

Let’s take a closer look at what’s going on.

Here are the ages of people who go to the Little Ducklings class.

The mean and median for the class are both 17, even though there are no 17-year-olds in the class!

Whichever value we choose for the average age, it seems misleading.