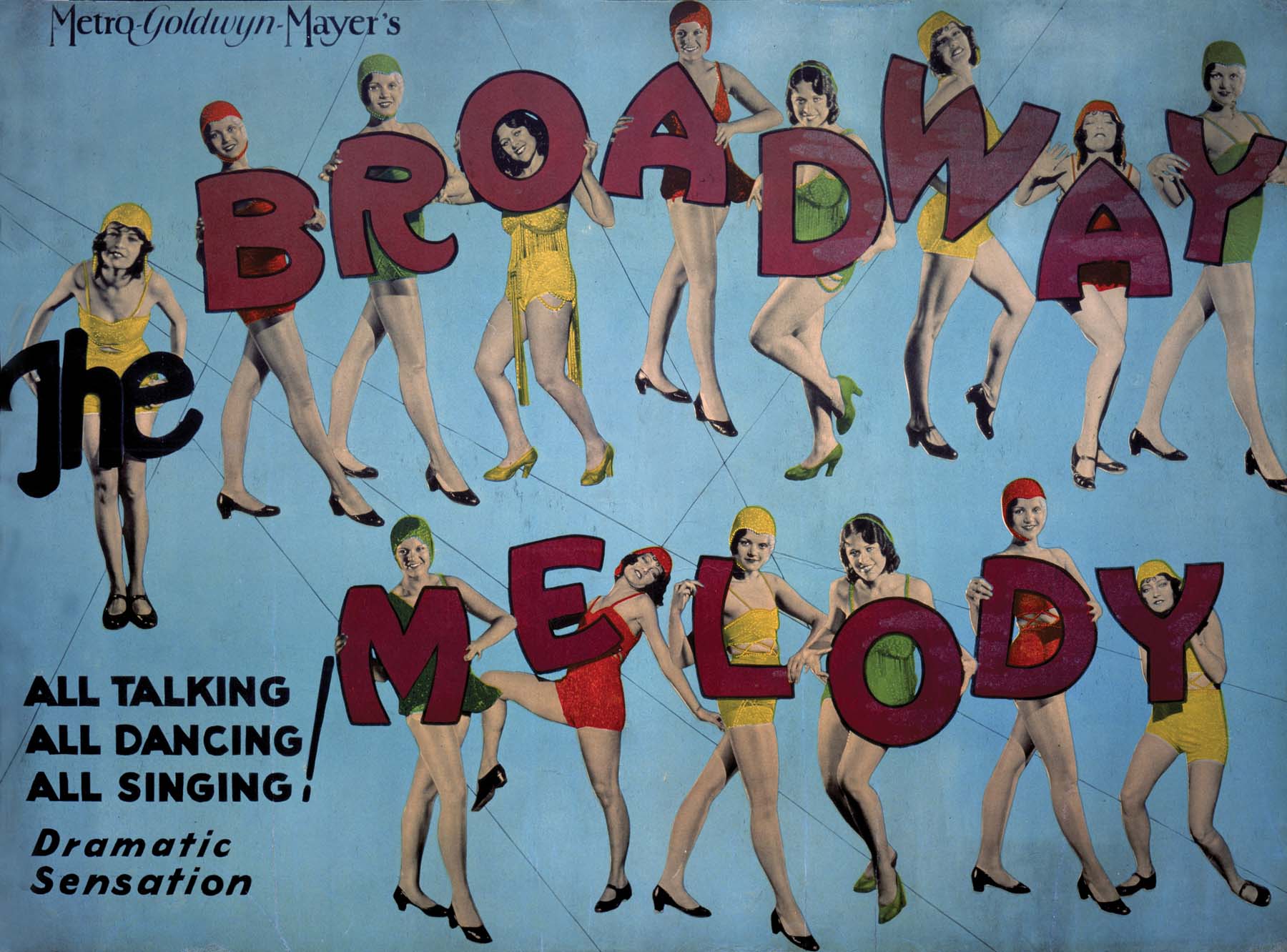

THE BROADWAY MELODY

MGM, 1929 | BLACK AND WHITE/COLOR (TECHNICOLOR), 100 MINUTES

DIRECTOR: HARRY BEAUMONT PRODUCERS: HARRY RAPF, IRVING THALBERG, LAWRENCE WEINGARTEN (UNCREDITED) SCREENPLAY: EDMUND GOULDING (STORY), SARAH Y. MASON (CONTINUITY), NORMAN HOUSTON AND JAMES GLEASON (DIALOGUE) SONGS: NACIO HERB BROWN (MUSIC) AND ARTHUR FREED (LYRICS) CHOREOGRAPHER: GEORGE CUNNINGHAM (UNCREDITED) STARRING: CHARLES KING (EDDIE KEARNS), ANITA PAGE (QUEENIE MAHONEY), BESSIE LOVE (HANK MAHONEY), JED PROUTY (UNCLE JED), KENNETH THOMSON (WARRINER), MARY DORAN (FLO), EDDIE KANE (FRANCIS ZANFIELD), DREW DEMOREST (TURPE, COSTUME DESIGNER), JOYCE MURRAY (SPECIALTY DANCER), JAMES GLEASON (MUSIC PUBLISHER)

Both members of a small-time sister act find love and disappointment after making it into a Broadway show.

To quote a later musical (specifically, The Sound of Music), let’s start at the very beginning. Where song-and-dance films are concerned, Square One is occupied by The Broadway Melody. The screen’s first real musical, it is responsible for everything that would follow. Everything.

Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer and The Singing Fool were crucial in bringing sound to movies; The Broadway Melody showed the world that they could sing and dance. At a time when other studios and filmmakers were struggling to solve the mysteries of sound, MGM boldly harnessed the new medium to create its first “all-talking” film, an out-and-out original musical. Based loosely on the real-life Duncan Sisters, it was greeted as the finest sound film yet made, seen and loved by millions. Its impact was immediate, and its influence and repercussions were so vast that by April 1930, when it won the Academy Award for Best Picture (or, as the Academy then called it, Outstanding Picture), it was both legendary and on its way to being obsolete.

That Academy Award win has become both a reference point and a kiss of death. More often than not, The Broadway Melody appears near the top of “Worst Best Picture Winners” lists, a status that is both understandable and unjust. As with many Oscar recipients, it’s timely entertainment, not timeless art, and as a very early sound film, it now seems as primitive and remote as a relic from the Bronze Age. The dialogue sounds as though they were still trying to figure out exactly how movie talk should sound, the cinematography is static, the musical numbers gauche, if charming, and the dramatics pretty threadbare.

So how, with all these distancing factors, can modern viewers confront such a museum piece? One way comes with perspective. Difficult as it may be, try to imagine how all this looked and sounded to an audience who had never before seen a musical. Next, recall that Singin’ in the Rain, a musical that truly is timeless, is in some ways a tribute to The Broadway Melody, using its songs and even some of its technical personnel; think of Broadway Melody as sort of a real-life Dancing Cavalier, with nobody getting dubbed. Another way comes with a performance that genuinely works. As Hank, Bessie Love is tough, vulnerable, subtle, and touching in a way no one had yet been in sound movies. (Watch Al Jolson in The Singing Fool [1928], then look at the scene where Hank breaks down. Case closed.) And, always, there is the history. This is where and how musicals got their start. Without it, there would be no 42nd Street (1933), no On the Town (1949), no Cabaret (1972) or Chicago (2002) or La La Land (2016). And, emphatically, no Singin’ in the Rain.

“The Wedding of the Painted Doll”