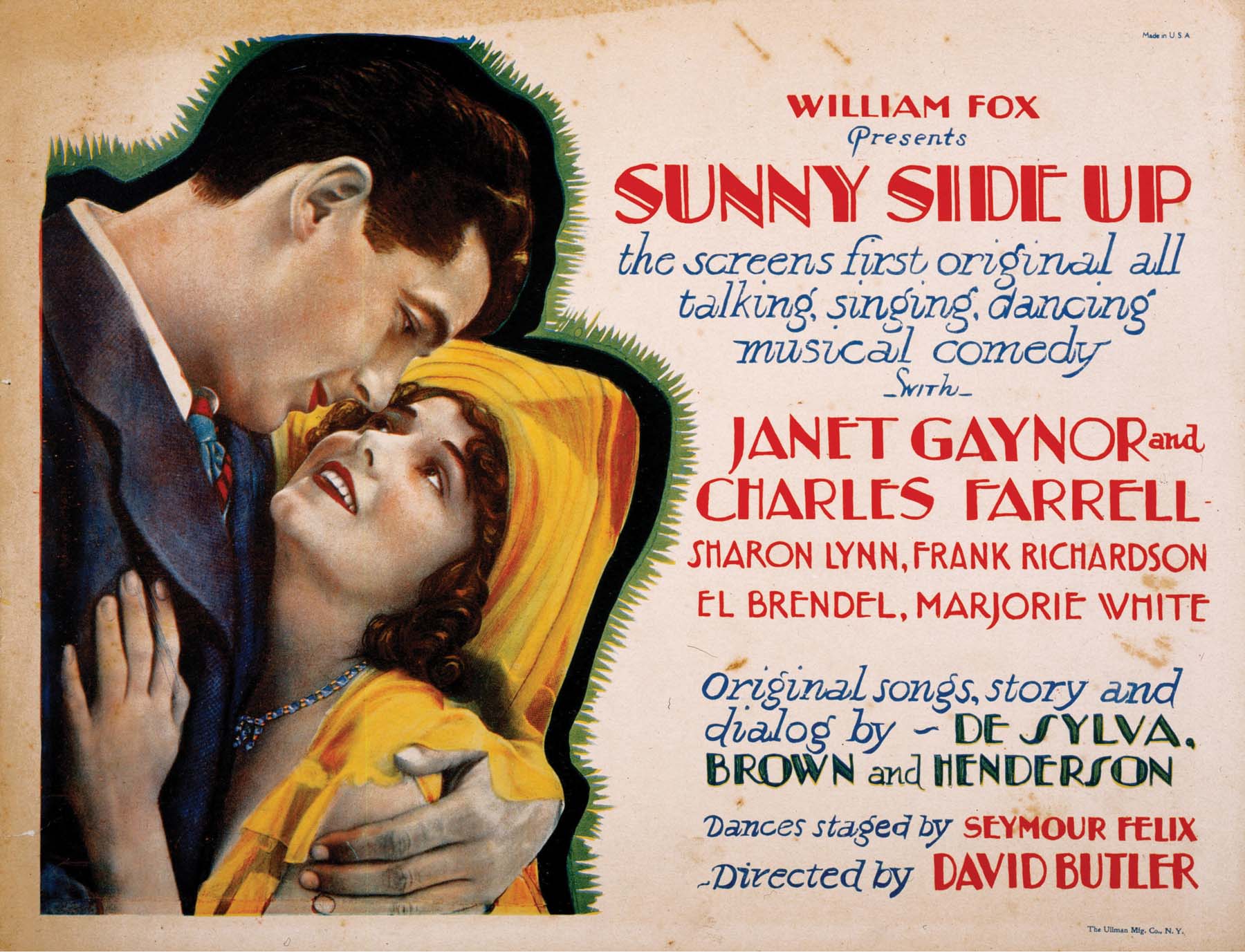

SUNNY SIDE UP

FOX, 1929 | BLACK AND WHITE, MULTICOLOR SEQUENCE IN SOME PRINTS, 121 MINUTES

DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER: DAVID BUTLER COPRODUCER: B. G. DESYLVA SCREENPLAY: B. G. DESYLVA, LEW BROWN, AND RAY HENDERSON, CONTINUITY BY DAVID BUTLER SONGS: B. G. DESYLVA, LEW BROWN, AND RAY HENDERSON CHOREOGRAPHER: SEYMOUR FELIX STARRING: JANET GAYNOR (MOLLY CARR), CHARLES FARRELL (JACK CROMWELL), MAJORIE WHITE (BEE NICHOLS), EL BRENDEL (ERIC SWENSON), MARY FORBES (MRS. CROMWELL), SHARON LYNN (JANE WORTH), FRANK RICHARDSON (EDDIE RAFFERTY), PETER GAWTHORNE (LAKE THE BUTLER), JACKIE COOPER (JERRY MCGINNIS [UNCREDITED])

To make his fiancée jealous, a Long Island socialite pretends to take up with a working girl.

An Original Musical Comedy,” the on-screen title card announces, and so it is. A sweet love story with dandy songs, this was one of the major hits of its era.

Other movie studios had Jolson or Garbo. Fox Films had Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell. She was petite and winsome, he was tall and handsome, and they set much of the world on fire in the silent romance Seventh Heaven. Neither had much in the way of vocal training, and Farrell’s nasally tenor voice seemed at odds with his appearance, but never mind. Their first all-talking picture, Fox decided, would be a musical created by prime Broadway talent. DeSylva, Brown, and Henderson, who created such hit shows as Good News, crafted a slight and engaging story that deliberately strayed from the then-rampant backstage formula. The songs were deftly tailored to the Gaynor-Farrell team’s limited vocal range, and Fox’s flexible sound equipment made it possible to do more outdoor shooting than was the case at other studios. The result was applauded by critics, who liked Gaynor more than Farrell, and massively embraced by audiences. Although some of the other early Fox musicals were disappointments, this one broke through as one of the year’s biggest successes, to be imitated and emulated ad infinitum.

While many early Fox talkies do not survive, this one fortunately does. Yes, it’s corny and runs too long, and then there’s Farrell’s voice and clueless line readings. What’s more important is the assurance of the filmmaking, which has little of the stolid quality or timidity that hinders so many 1929 films. It really does act and move like a film, instead of a transplanted stage show, and Gaynor carries the whole thing like a major-league pro. Take a small voice, add a middling-but-spirited affinity for song and dance, and surround the whole of it with a touching kind of sincerity rare in any actor. She means this performance, whether doing her hat-and-cane bit in the title song, being optimistic or tearful, or duetting with Farrell on “If I Had a Talking Picture of You.” (If ever the early sound era had an anthem, this is it.) When she settles into a comfy chair, pulls out an autoharp, and begins to strum and sing “I’m a Dreamer (Aren’t We All?),” a viewer can be momentarily struck by how strange it is, how foreign to later performances and styles. Then, after a few moments, it begins to work: she’s looking straight into the camera and out into the audience, she believes every word she’s singing, and darned if that authenticity doesn’t convince even the unbelievers. Musical film needs sincerity as much as, or more than, it does plush spectacle, big effects, devastating talent. Even this early in the game, an intuitive performer like Janet Gaynor can show what, in a musical, can matter the most.

As with the best and most important musicals, the value of Sunny Side Up lies both in its own beguiling self and in its influence. Love stories with songs begin here, and if the path to a La La Land is long, it’s quite direct. One would never have happened without the other.

“Keep Your Sunny Side Up”: Janet Gaynor

WHAT’S MORE

At a time when cameras were mostly nailed down, director David Butler opens this film with a long, roving crane shot of a Manhattan tenement, the camera and microphone picking up tiny vignettes in every apartment window. It works as both a preface for the main action and as a stand-alone virtuoso flourish. It may even seem vaguely familiar: it anticipates the beginning, twenty-five years later, of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.

Janet Gaynor’s on-screen sweetness was equaled, off camera, by a sturdy, determined sense of what was and wasn’t good for her career. After the triumph of Sunny Side Up, Fox immediately dumped her and Farrell into an atrocious musical follow-up called High Society Blues. It was, essentially, Sunny Side Up without the good parts, and despite its financial success an appalled Gaynor knew that drastic measures were in order. Walking out on her studio and contract, she embarked on a strike for better roles and higher salary. It went on for seven months, a career eternity in 1930. And she won. As director Butler later noted admiringly, Gaynor had guts.

MUSICALLY SPEAKING

While most of the songs in Sunny Side Up are staged on a small scale, one doozy of a showstopper rolls in as part of the big society benefit. As performed by Sharon Lynn and an enthusiastic group of dancers, “Turn on the Heat” is a tribute to love in both the Arctic, with igloos, and the tropics, with bananas. The dance director, Seymour Felix, kindly saw to it that not one phallic allusion would be overlooked, nor one dancer show any inhibition or propriety. What it lacks in taste, it more than makes up for in sheer brass.

Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell